Transforming the Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years

The Supreme Court of Western Australia 1861 - 2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 years by The Honourable Wayne Martin Chief Justice of Western Australia Ceremonial Sitting - Court No 1 17 June 2011 Ceremonial Sitting - Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years The court sits today to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the creation of the court. We do so one day prematurely, as the ordinance creating the court was promulgated on 18 June 1861, but today is the closest sitting day to the anniversary, which will be marked by a dinner to be held at Government House tomorrow evening. Welcome I would particularly like to welcome our many distinguished guests, the Rt Hon Dame Sian Elias GNZM, Chief Justice of New Zealand, the Hon Terry Higgins AO, Chief Justice of the ACT, the Hon Justice Geoffrey Nettle representing the Supreme Court of Victoria, the Hon Justice Roslyn Atkinson representing the Supreme Court of Queensland, Mr Malcolm McCusker AO, the Governor Designate, the Hon Justice Stephen Thackray, Chief Judge of the Family Court of WA, His Honour Judge Peter Martino, Chief Judge of the District Court, President Denis Reynolds of the Children's Court, the Hon Justice Neil McKerracher of the Federal Court of Australia and many other distinguished guests too numerous to mention. The Chief Justice of Australia, the Hon Robert French AC had planned to join us, but those plans have been thwarted by a cloud of volcanic ash. We are, however, very pleased that Her Honour Val French is able to join us. I should also mention that the Chief Justice of New South Wales, the Hon Tom Bathurst, is unable to be present this afternoon, but will be attending the commemorative dinner to be held tomorrow evening. -

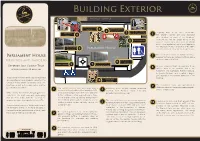

Self-Guided Tour – Parliament Grounds

HAVELOCK ST Building Exterior Pedestrian crossing Harvest Terrace Lion and Unicorn Western Façade of Statues 5 Parliament House Private Car Park 6 North-west corner Originally built as an open colonnade, Adjoining 7 of Parliament House 6 Walls 4 the western arches are now enclosed with windows as part of the Members’ Iron Sculpture Dining Room. The two green doors on the (Western Side) 8 western façade were once used for official entry to the Legislative Council and Legislative The Southern Assembly prior to the completion of the 1960s Extension 3 Parliament House eastern extension. They are no longer in use. HAY 7 The north-west corner of Parliament House Parliament House (Eastern Side) became the final majorST extension of the building W Main Entrance and was completed in 2004. The Foundation Grounds and Gardens S N (Eastern Side) Eastern Façade of 9 Stone Sunken Gardens 2 1 One Exterior Self-Guided Tour E Parliament House An iron sculpture forms an enclosure to an 8 alfresco area at theWay northern end of the Approximately 20 minutes Parliament. The Australiana themed windows, by Jennifer Cochrane, were installed in August W 2003 as part of the northern extensions of the The grounds of Parliament House are regarded building. as a prestigious and symbolic venue for the Pensioners 10 Barracks S N conduct of important ceremonies and civic functions, as well as for public rallies and the 9 The foundation stone was repositioned in presentation of petitions. The eastern façade was authorised during Adjoining walls of 1903 contain lime-stone 1964 to sit within the completed eastern façade, 1 4 where it remains today. -

Wellington's Men in Australia

Wellington’s Men in Australia Peninsular War Veterans and the Making of Empire c. 1820–40 Christine Wright War, Culture and Society, 1750 –1850 War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors: Rafe Blaufarb (Tallahassee, USA), Alan Forrest (York, UK), and Karen Hagemann (Chapel Hill, USA) Editorial Board: Michael Broers (Oxford UK), Christopher Bayly (Cambridge, UK), Richard Bessel (York, UK), Sarah Chambers (Minneapolis, USA), Laurent Dubois (Durham, USA), Etienne François (Berlin, Germany), Janet Hartley (London, UK), Wayne Lee (Chapel Hill, USA), Jane Rendall (York, UK), Reinhard Stauber (Klagenfurt, Austria) Titles include: Richard Bessel, Nicholas Guyatt and Jane Rendall (editors) WAR, EMPIRE AND SLAVERY, 1770–1830 Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson (editors) THE BEE AND THE EAGLE Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806 Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann and Jane Rendall (editors) SOLDIERS, CITIZENS AND CIVILIANS Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1820 Karen Hagemann, Gisela Mettele and Jane Rendall (editors) GENDER, WAR AND POLITICS Transatlantic Perspectives, 1755–1830 Marie-Cécile Thoral FROM VALMY TO WATERLOO France at War, 1792–1815 Forthcoming Michael Broers, Agustin Guimera and Peter Hick (editors) THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE AND THE NEW EUROPEAN POLITICAL CULTURE Alan Forrest, Etienne François and Karen Hagemann (editors) WAR MEMORIES The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Europe Leighton S. James WITNESSING WAR Experience, Narrative and Identity in German Central Europe, 1792–1815 Catriona Kennedy NARRATIVES OF WAR Military and Civilian Experience in Britain and Ireland, 1793–1815 Kevin Linch BRITAIN AND WELLINGTON’S ARMY Recruitment, Society and Tradition, 1807–1815 War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Standing Order ISBN 978–0–230–54532–8 hardback 978–0–230–54533–5 paperback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Perth's Engineering Heritage Walking Tour Guide

CELEBRATING 100 YEARS OF PERTH’S ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA ENGINEERING HERITAGE CELEBRATING 100 YEARS ENGINEERING This walking tour was developed as part of EngineersOF ENGINEERS Australia’s Centenary celebrations. AUSTRALIA HERITAGECITY WALKING TOURS CITY WALKING TOURS Scan the symbol below to access a detailed online In T2019his walking we at Engineers tour was Australia developed are celebrating as part of Engineers walking tour and over 70 different sites around the city Australia’s Centenary celebrations. In 1919 … etc etc Scan the symbol below to access a detailed online our Centenary. with engineering significance. walking tour and over 70 different sites around the We are proud of the work that we have done to help cityChoose with engineeringyour favourite significance. sites from the list overleaf, or shape the profession – a profession that is integral to every field of human endeavour. Choosefollow one your of favourite the suggested sites from tour the routes. list overleaf, PERTH’S or follow one of the suggested tour routes. But this is not only about our organisation – this is CITY WEST WALK (4.5 km, moderate) a celebration of Australian engineers who pushed ENGINEERING boundaries, defied odds, and came up with innovations Meet the engineers who built Western Australia and that no-one could have imagined 100 years ago. Driven by a sense that anything is possible, engineers have HERITAGE CITYdiscover WEST Perth’s WALK first water supplies (6km, and moderate) modern shaped our world. Who knows where it will take us in the transport marvels. Meet the engineers who built Western Australia and discover next 100 years. -

Swamp : Walking the Wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2012 Swamp : walking the wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain ; and with the exegesis, A walk in the anthropocene: homesickness and the walker-writer Anandashila Saraswati Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation Saraswati, A. (2012). Swamp : walking the wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain ; and with the exegesis, A walk in the anthropocene: homesickness and the walker-writer. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/588 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/588 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. USE OF THESIS This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. However, the literary rights of the author must also be respected. If any passage from this thesis is quoted or closely paraphrased in a paper of written work prepared by the user, the source of the passage must be acknowledged in the work. -

REGISTER of HERITAGE PLACES DRAFT – Register Entry

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES DRAFT – Register Entry 1. DATA BASE No. 2239 2. NAME Parliament House & Grounds (1902-04, 1958-64, 1971,1978) 3. LOCATION Harvest Terrace & Malcolm Street, West Perth 4. DESCRIPTION OF PLACE INCLUDED IN THIS ENTRY 1. Reserve 1162 being Lot 55 on Deposited Plan 210063 and being the whole of the land comprised in Crown Land Title Volume LR3063 Folio 455 2. Reserve 45024 being (firstly) Lot 836 on Deposited Plan 210063 and being the whole of the land comprised in Crown Land Title Volume LR3135 Folio 459 and (secondly) Lot 1083 on Deposited Plan 219538 being the whole of the land comprised in Crown Land Title Volume LR3135 Folio 460. 5. LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA City of Perth 6. CURRENT OWNER 1. State of Western Australia (Responsible Agency: Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage; Management Order: Parliamentary Reserve Board Corporate Body) 2. State of Western Australia (Responsible Agency: Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage) 7. HERITAGE LISTINGS • Register of Heritage Places: Interim Entry 24/09/2004 • National Trust Classification: Classified 11/10/2004 • Town Planning Scheme: Yes 09/01/2004 • Municipal Inventory: Adopted 13/03/2001 • Register of the National Estate: ---------------- • Aboriginal Sites Register ---------------- 8. ORDERS UNDER SECTION OF THE ACT ----------------- Register of Heritage Places Parliament House & Grounds 1 Place Assessed April 2003 Documentation amended: August 2010; April 2020; July 2020 9. HERITAGE AGREEMENT ----------------- 10. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE Parliament House & Grounds, a two and three storey stone and tile building in the Federation Academic Classical (1904) and Late Twentieth Century Stripped Classical styles (1964), with landscaped grounds, has cultural heritage significance for the following reasons: the place is a symbol of the establishment of State government in Western Australia and provides a strong sense of historical continuity in its function. -

Images of the Caribbean : Materials Development on a Pluralistic Society

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1982 Images of the Caribbean : materials development on a pluralistic society. Gloria. Gordon University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Gordon, Gloria., "Images of the Caribbean : materials development on a pluralistic society." (1982). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2245. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2245 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OP THE CARIBBEAN - MATERIALS DEVELOPMENT ON A PLURALISTIC SOCIETY A Dissertation Presented by Gloria Mark Gordon Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 1 982 School of Education © 1982 GLORIA MARK GORDON All Rights Reserved IMAGES OF THE CARIBBEAN - MATERIALS DEVELOPMENT ON A PLURALISTIC SOCIETY A Dissertation Presented by Gloria Mark Gordon Approved as to style and content by: Georg? E. Urch, Chairperson ) •. aJb...; JL Raljih Faulkinghairi, Member u l i L*~- Mario FanbfLni , Dean School of (Education This work is dedicated to my daughter Yma, my sisters Carol and Shirley, my brother Ainsley, my great aunt Virginia Davis, my friend and mentor Wilfred Cartey and in memory of my parents Albert and Thelma Mark iii . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work owes much, to friends and colleagues who provided many elusive forms of sustenance: Ivy Evans, Joan Sandler, Elsie Walters, Ellen Mulato, Nana Seshibe, Hilda Kokuhirwa, Colden Murchinson, Sibeso Mokub. -

Spotlight On

1 September-October 2000 No. 249 Official Newsletter of The Library and Information Service of Western Australia Spotlight on.... - Y o u r G u i d e t o K n o w l e d g e state reference library state2 Welcome to the referenceWelcome library state reference second special edition to the State Reference Library of knowit. This issue library state reference library state focuses on the State Reference Library referenceCultural monuments library such as services as well as museums, art galleries and state statelibraries are allreference too often seen as LYNN including the second issue of the libraryan obligation rather thanstate a means Professional Journal. to a cultural end. I’m happy to report the reference library State Records Bill This issue of knowit celebrates the stateState Referencereference Library of Lynn Allen (CEO and State Librarian) (1999) is passing FROM Western Australia. through Parliament having had its second reading library state Claire Forte in the Upper House. We are all looking forward to (Director: State Reference Library) The State Reference Library this world leading legislation being proclaimed. reference library covers the full range of classifiable written knowledge in much the same way as a public library. As you I hope many of you will be able to visit the Centre state reference library state might expect in a large, non-circulating library, the line line line for the Book on the Ground Floor of the Alexander line line referencebreadth of material library on the shelves state is extensive. reference Library Building to view the current exhibition Quokkas to Quasars - A Science Story which library state reference library state A We also have specialist areas such as business, film highlights the special achievements of 20 Western and video, music, newspapers, maps, family history Australian scientists. -

A Colony of Convicts

A Colony of Convicts The following information has been taken from https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/ Documenting a Democracy ‘Governor Phillip’s Instructions 25 April 1787’ The British explorer Captain James Cook landed in Australia in 1770 and claimed it as a British territory. Six years after James Cook landed at Botany Bay and gave the territory its English name of 'New South Wales', the American colonies declared their independence and war with Britain began. Access to America for the transportation of convicts ceased and overcrowding in British gaols soon raised official concerns. In 1779, Joseph Banks, the botanist who had travelled with Cook to New South Wales, suggested Australia as an alternative place for transportation. The advantages of trade with Asia and the Pacific were also raised, alongside the opportunity New South Wales offered as a new home for the American Loyalists who had supported Britain in the War of Independence. Eventually the Government settled on Botany Bay as the site for a colony. Secretary of State, Lord Sydney, chose Captain Arthur Phillip of the Royal Navy to lead the fleet and be the first governor. The process of colonisation began in 1788. A fleet of 11 ships, containing 736 convicts, some British troops and a governor set up the first colony of New South Wales in Sydney Cove. Prior to his departure for New South Wales, Phillip received his Instructions from King George III, with the advice of his ‘Privy Council'. The first Instructions included Phillip's Commission as Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of New South Wales. -

SUFFOLK RECORD OFFICE Ipswich Branch Reels M941-43

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SUFFOLK RECORD OFFICE Ipswich Branch Reels M941-43 Suffolk Record Office County Hall Ipswich Suffolk IP4 2JS National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1975 CONTENTS Page 3 Ipswich Borough records, 1789-1887 3 Parish records, 1793-1962 9 Deeds of Tacket Street Congregational Church, 1880-84 9 Papers of Rous Family, Earls of Stradbroke, 1830-1926 11 Papers of Rope Family of Blaxhall, 1842 12 Papers of Loraine Family of Bramford Hall, 1851-1912 13 Papers of Augustus Keppel, Viscount Keppel, 1740-44 14 Papers of Admiral Frederick Doughty, 1848-73 14 Papers of Greenup Family, 1834-66 15 Papers of Bloomfield Family of Redham, 1845-52 15 Papers of Harold Lingwood relating to Margaret Catchpole, 1928-54 16 Letter of Lt. Col. William Donnan, 1915 2 SUFFOLK RECORD OFFICE Ipswich Branch Reel M941 Ipswich Borough Records C/2/9/1 General Quarter Sessions, 1440-1846 C/2/9/1/11 Miscellanea [previously C1/2/29] Select: 5 Papers regarding transportation of Susanna Hunt, 1789 Contract between Ipswich Corporation and William Richards for the conveyance of Susanna Hunt, wife of John Hunt, to Botany Bay, 1 April 1789. Hunt had been convicted of grand larceny and was sentenced to transportation for seven years. Bond by William Richards and George Aitkin (Deptford) in £80 to carry out contract, 2 April 1789. William Richards (Walworth) to keeper of Ipswich Gaol, 9 April 1789: encloses bond. William Richards to George Aitkin (Lady Juliana), 4 April 1789: instructs him to receive one female convict from Suffolk. -

Discovering Perth's Iconic Architecture Tom

BUILT PERTH DISCOVERING PERTH’S ICONIC ARCHITECTURE TOM MCKENDRICK AND ELLIOT LANGDON CONTENTS Introduction 3 St George’s Cathedral 60 CIVIC HOSPITALITY Western Australian Museum 4 Yagan Square 62 City of Perth Library 6 Royal George Hotel 64 Perth Town Hall 8 Indiana Cottesloe 66 Parliament House 10 Former Titles Office 68 The Bell Tower 12 Old Treasury Buildings 70 Barracks Arch 14 OFFICE City Beach Surf Club 16 QV1 72 Fremantle Prison 18 Allendale Square 74 Perth GPO 20 Former David Foulkes Government House 22 Taylor Showroom 76 Council House 24 Palace Hotel and Criterion Hotel 26 108 St Georges Terrace 78 Fremantle Arts Centre 28 London Court 80 Perth Children’s Hospital 30 Gledden Building 82 Fremantle Town Hall 32 Supreme Court of Western SELECTED HOUSING STYLES 84 Australia 34 RESIDENTIAL Fremantle Ports Administration Mount Eliza Apartments 86 Building 36 Paganin House 88 BRIDGE STYLES 38 32 Henry Street Apartments 90 EDUCATION Warders’ Cottages 92 Victoria Avenue House 94 West Australian Ballet Heirloom by Match 96 Company Centre 40 Blue Waters 98 Winthrop Hall 42 Soda Apartments 100 St George’s College 44 Cloister House 102 ENTERTAINMENT Chisholm House 104 Regal Theatre 46 INDUSTRIAL His Majesty’s Theatre 48 ‘Dingo’ Flour Mill 106 Perth Stadium 50 Perth Concert Hall 52 Glossary 108 Perth Arena 54 Acknowledgements 110 State Theatre Centre of About the authors 110 Western Australia 56 Index 111 SPIRITUAL Cadogan Song School 58 INTRODUCTION In the relatively short space of time in Perth, the book is a gentle tap on can only serve as a guide because since the Swan River Colony was the shoulder, a finger which points many of the records are incomplete established, Perth has transformed upwards and provides a reminder of or not public information. -

Henry Prinsep's Empire: Framing a Distant Colony

Henry Prinsep’s Empire: Framing a distant colony Henry Prinsep’s Empire: Framing a distant colony Malcolm Allbrook Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Allbrook, Malcolm, author. Title: Henry Prinsep’s empire : framing a distant colony / Malcolm Allbrook. ISBN: 9781925021608 (paperback) 9781925021615 (ebook) Subjects: Prinsep, Henry Charles 1844-1922. East India Company. Artists--Western Australia--Biography. Civil service--Officials and employees--Biography. Western Australia--Social life and customs--19th century. India--Social life and customs--19th century. Dewey Number: 759.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Dedication . vii Acknowledgments . ix Biographical Sketches of the Family of Henry Charles Prinsep (1844‑1922) . xi 1 . Introduction—An Imperial Man and His Archive . 1 Henry Prinsep’s colonial life . 1 Histories across space, place and time . 8 Accessing the Prinsep archive . 13 2 . Images of an Imperial Family . 27 A novelised and memorialised India . 27 Governing the others . 35 Scholarliness and saintliness . 42 A place to make a fortune . 48 Military might: The limits of violence . 54 A period of imperial transformation . 57 3 . An Anglo‑Indian Community in Britain .