Redalyc.Deciphering Aborigines and Migrants from Cognation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecto and Endo Parasites of Domestic Birds in Owan West, East and Akoko-Edo in Edo State of Nigeria

Annals of Reviews and Research Research Article Ann Rev Resear Volume 4 Issue 1- October 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Igetei EJ Ecto and Endo Parasites of Domestic Birds in Owan West, East and Akoko-Edo in Edo State of Nigeria Edosomwan EU and Igetei EJ* Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, University of Benin, Nigeria Submission: March 16, 2018; Published: October 16, 2018 *Corresponding author: Igetei EJ, Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, Benin city, Nigeria; Email: Abstract Twenty-three (23) live domestic birds comprising of 13 chickens (Gallus gallus domestica), 6 ducks (Anas sparsa), and 4 pigeons (Columbia livie) distributed across 3 Local Government Council Areas (LGAs) in Owan West, East and Akoko-Edo of Edo State, Nigeria, was screened for ecto- and endo-parasites. In addition, two hundred (200) faecal samples from 200 domestic birds distributed across the 3 LGAs were investigated for endoparasites. From the 23 live birds, nine species of ectoparasite (Mallophaga-lice), were recovered, of which Menopon gallinae recorded the highest prevalence (23.33%), while Coclutogaster heterographus recorded the least (3.33%). 162 of the 223 birds (23 live birds + 200 faecal samples) investigated were positive for endoparasites recording an overall prevalence of 72.65%. From these hosts, 25 species of endo-helminths comprising of 9 species of cestode; 13 species of nematode; 3 species of trematode and some protozoan sporocysts were recovered. Raillietina tetragona recorded the highest overall prevalence (20.40%), while Amidostomum anseris recorded the least with a prevalence of 0.20%. All 13 live chickens (100%) and 2 pigeons (50%) were observed to be infected with endoparasites. -

Groundwater Quality Determination from Hand-Dug Wells in Ososo Town, Akoko-Edo North Local Government Area Edo State

Nigerian Journal of Technology Vol. 40, No. 3, May, 2021, pp. 540–549. www.nijotech.com Print ISSN: 0331-8443 Electronic ISSN: 2467-8821 http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v40i3.20 Groundwater Quality Determination from Hand-Dug Wells in Ososo Town, Akoko-Edo North Local Government Area Edo State E. G. Maju-Oyovwikowhe¤, W. O. Emofurieta¤ Department of Geology, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, NIGERIA. Abstract Groundwater is water beneath the surface of the earth. The primary source is precipitation from rain, snow, and hail. Groundwater commonly occurs as water that fills pore spaces between mineral or rock grains in sediments and sedimentary rocks. This study is to evaluate the physiochemical characteristics and selected heavy metal levels of Water from Hand Dug Wells in Ososo in Akoko Edo Local Government Area of Edo State, Nigeria. A total of twenty (20) water samples were collected in very clean containers from twenty (20) hand dug wells in Ososo town, and taken to the laboratory immediately for physical, chemical and heavy metal analysis using standard laboratory techniques. The physical analysis results from the study show that depth to ground water is very shallow. Ph was below 7.5. Conductivity varies from 167.8-2120.00 /cm. The temperatures were uniform. The ground water is odorless and tasteless. The amounts of total suspended soil (TSS) in all the samples vary from 10–20 ppm. The total dissolved solid content (TDS) concentration for all the samples varies from 132–1320.00 ppm. Total hardness is soft to moderately hard. Total alkalinity values vary between 3.0 to 18.0 ppm. -

Map of Edo State

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND YOU ARE ADVISED TO CAREFULLY READ AND UNDERSTAND ITS CONTENTS. IF YOU ARE IN DOUBT ABOUT ITS CONTENTS OR THE ACTION TO TAKE, PLEASE CONSULT YOUR STOCKBROKER, SOLICITOR, BANKER OR AN INDEPENDENT INVESTMENT ADVISER. THIS PROSPECTUS HAS BEEN SEEN AND APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE EDO STATE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL AND THEY JOINTLY AND INDIVIDUALLY ACCEPT FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ACCURACY OF ALL INFORMATION GIVENTHIS DOCUMENTAND CONFIRM IS IMPORTANT THAT, AFTERAND YOU HAVING ARE ADVISED MADE TO INQUIRIES CAREFULLY WHICHREAD AND ARE UNDERSTAND REASONABLE ITS IN THE CIRCUMSTANCES ANDCONTENTS. TO THE IFBEST YOU OF ARE THEIR IN DOUBT KNOWLEDGE ABOUT ITS AND CONTENTS BELIEF, OR THERE THE ACTIONARE NO TO OTHER TAKE, FACTS, PLEASE THE CONSULT OMISSION YOUR OF WHICH WOULD MAKE ANY STOCKBROKER,STATEMENT HEREIN SOLICITOR, MISLEADING. BANKER OR AN INDEPENDENT INVESTMENT ADVISER. THIS PROSPECTUS HAS BEEN For information concerningSEEN certainAND APPROVED risk factors BY which THE shouldMEMBERS be considered OF THE EDO by STATEprospective EXECUTIVE investors, COUNCIL see risk AND factors THEY on pageJOINTLY 77. AND INDIVIDUALLY ACCEPT FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ACCURACY OF ALL INFORMATION GIVEN AND CONFIRM THAT, AFTER HAVING MADE INQUIRIES WHICH ARE REASONABLE IN THE CIRCUMSTANCES AND TO THE BEST OF THEIR KNOWLEDGE AND BELIEF, THERE ARE NO OTHER FACTS, THE OMISSION OF WHICH WOULD MAKE ANY STATEMENT HEREIN MISLEADING. For information concerning certain risk factors which should be considered by prospective investors, see risk -

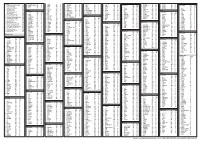

Independent National Electoral Commission (Inec)

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: EDO LGA : AKOKO EDO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) COLLATION CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) IGARRA GIRLS GRAM. SCH. 1 IGARRA 1 01 ETUNO MODEL PRY SCH. IGARRA ST. PAUL ANG. GRAM. SCH. ST.PAUL.ANG.GRAM.SCH. 2 IGARRA 11 02 IGARRA IGARRA IMOGA / LAMPESE / BEKUMA / LOCAL GOVT.TRAINING CENTRE 3 03 UKILEPE PRY SCH LAMPESE EKPE BEKUMA IBILO / EKPESA / EKOR / KIRAN- 4 04 AZANE PRY. SCH. IBILO FEDERAL GOVT. COL.IBILO ILE / KIRAN-OKE MAKEKE / OJAH / DANGBAL / DANGBALA PRYNG.SCH. 5 05 DANGBALA PRY. SCH. DANGBALA OJIRAMI / ANYANWOZA DANGBALA OLOMA / OKPE / IKAKUMO / 6 06 AJAMA PRY. SCH. OKPE AJAMA PR. SCH.OKPE NYANRAN SOMORIKA / OGBE / SASARO / 7 ONUMU / ESHAWA / OGUGU / 07 L.G. DINPENSARY AIYEGUNLE EKUGBE SEC. SCH. AIYEGUNLE IGBOSHI-AFE & ELE / ANYEGUNLE ENWAN / ATTE / IKPESHI / 8 08 IKPESHIM GRAM. SCH.IKPESHI IKPESHI. GRAM. SCH. IKPECHI EGBEGERE UNEME-NEKUA / AKPAMA / 9 AIYETORO / EKPEDO / ERHURRUN 09 OGUN PRY SCH. EKPEDO OGUN PRY. SCH. EKPEDO / UNEME / OSU 10 OSOSO 10 OKUNGBE PRY SCH. OSOSO OKUNGBE PRY. SCH. OSOSO TOTAL LGA : EGOR CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) COLLATION CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 OTUBU 01 ASORO GIBA SCH. ASORO GIBA SCH. 2 OLIHA 02 AUNTY MARIA SCH. AUNTY MARIA SCH. 3 OGIDA/ USE 03 EWGAA P/S EWGAA P/S 4 EGOR 04 EGOR P/S EGOR P/S 5 UWELU 05 UWELU SEC.SCH. UWELU SEC.SCH. 6 EVBAREKE 06 EVBAREKE GRAM.SCH. -

SERIAL VIOLATIONS, Edo State Campaign Finance Report

SERIAL VIOLATIONS (A Report on Campaign Finance and use of State Administrative Resources in the EDO STATE 2016 Gubernatorial Election) CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) SERIAL VIOLATIONS (A Report on Campaign Finance and use of State Administrative Resources in the Edo State 2016 Gubernatorial Election) CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) Serial Violations Page ii SERIAL VIOLATIONS (A Report on Campaign Finance and use of State Administrative Resources in the Edo State 2016 Gubernatorial Election) Written by Eze Onyekpere and Kingsley Nnajiaka CSJ Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice in Public Life) Serial Violations Page iii First Published in 2017 By Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) No.17, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418, Garki Abuja Tel: 08055070909, 08127235995 Website: www.csj-ng.org Email: [email protected] Twitter: @censoj Facebook: Centre for Social Justice, Nigeria Blog: csj-blog.org Copyright @ CSJ CSJ asserts the copyright to this publication, but nevertheless permits photocopying or reproduction of extracts, provided due acknowledgement is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extracts is sent to the above address. Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) Serial Violations Page iv Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.1. Background 1 1.2. Goals and Objectives 4 1.3. Context of the 2016 Edo Gubernatorial Contest 4 1.4. Methodology 5 1.5. Challenges and Limitation of the Monitoring Exercise 6 1.6. Presentation of the Report 7 Chapter Two: The Legal Framework 8 2.1. -

ZONAL INTERVENTION PROJECTS Federal Goverment of Nigeria APPROPRIATION ACT

2014 APPROPRIATION ACT ZONAL INTERVENTION PROJECTS Federal Goverment of Nigeria APPROPRIATION ACT Federal Government of Nigeria 2014 APPROPRIATION ACT S/NO PROJECT TITLE AMOUNT AGENCY =N= 1 CONSTRUCTION OF ZING-YAKOKO-MONKIN ROAD, TARABA STATE 300,000,000 WORKS 2 CONSTRUCTION OF AJELE ROAD, ESAN SOUTH EAST LGA, EDO CENTRAL SENATORIAL 80,000,000 WORKS DISTRICT, EDO STATE 3 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE, OTADA, OTUKPO, BENUE STATE (ONGOING) 150,000,000 YOUTH 4 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE, OBI, BENUE STATE (ONGOING) 110,000,000 YOUTH 5 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE, AGATU, BENUE STATE (ONGOING) 110,000,000 YOUTH 6 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-MPU,ANINRI LGA ENUGU STATE 70,000,000 YOUTH 7 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-AWGU, ENUGU STATE 150,000,000 YOUTH 8 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-ACHI,OJI RIVER ENUGU STATE 70,000,000 YOUTH 9 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-NGWO UDI LGA ENUGU STATE 100,000,000 YOUTH 10 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE- IWOLLO, EZEAGU LGA, ENUGU STATE 100,000,000 YOUTH 11 YOUTH EMPOWERMENT PROGRAMME IN LAGOS WEST SENATORIAL DISTRICT, LAGOS STATE 250,000,000 YOUTH 12 COMPLETION OF YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE AT BADAGRY LGA, LAGOS 200,000,000 YOUTH 13 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE IN IKOM, CROSS RIVER CENTRAL SENATORIAL DISTRICT, CROSS 34,000,000 YOUTH RIVER STATE (ON-GOING) 14 ELECTRIFICATION OF ALIFETI-OBA-IGA OLOGBECHE IN APA LGA, BENUE 25,000,000 REA 15 ELECTRIFICATION OF OJAGBAMA ADOKA, OTUKPO LGA, BENUE (NEW) 25,000,000 REA 16 POWER IMPROVEMENT AND PROCUREMENT AND INSTALLATION OF TRANSFORMERS IN 280,000,000 POWER OTUKPO LGA (NEW) 17 ELECTRIFICATION OF ZING—YAKOKO—MONKIN (ON-GOING) 100,000,000 POWER ADD100M 18 SUPPLY OF 10 NOS. -

Analysis of Spatial Distribution of Health Care Facilities in Owan East and Owan West Local Government Areas of Edo State

ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF HEALTH CARE FACILITIES IN OWAN EAST AND OWAN WEST LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS OF EDO STATE Dr. Ojeifo, O. Magnus Abstract This study examines the distribution and accessibility to hospital and primary health care facilities in Owan East and Owan West local government areas of Edo Stale. The study utilized data obtained mainly from field surveys. 40 settlements located in each of the 11 wards of the local government areas were covered. There are three general and one-district hospitals, and 30 primary health care centers that are randomly distributed in the area. This distribution did not however favour many settlements as accessibility was observed to be a problem. Accessibility to the hospitals was though high compared with the WHO standard but not all settlements were however adequately covered. Access to PHC's was found to be low compared with the WHO standard. Adequate planning and the provision of health and other public facilities were recommended to overcome the problem of distribution and accessibility to health care services in the area. Introduction The wealth of any nation is dependent on the health of its citizenry. Health according to the World Health Organization (1978) is the state of complete physical, mental and social well-being. A nation is therefore healthy if the mental and physical needs of the generality of its citizens are adequately met (Agbonifor, 1981). These needs according to Omofonmwan (1994) include water supply, access roads, housing, education and health care facilities. Health is paramount in a nation's quest for development. It is only a healthly people that may have the ability to exploit and develop a nation's resources for their overall well-being. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Advert List 202 11 June, 2021

Advert List 202 11 June, 2021 ADVERTISEMENT of APPLICANTS FOR LAND REGISTRATION 1. The underlisted applications have been received under the Land Use Decree of 1978 for grant of Statutory Right of Occupancy. 2. Any member of the public who may wish to object to any of the applications below should do so within 21 days of this publication. 3. Notice of objection should be accompanied with the copies of a sworn affidavit, evidence of ownership of title and a non-refundable fee of N20,000 (Twenty thousand Naira) for each objection and addressed to the Managing Director, Edo State Geographic Information Service, 102 Sapele Road, Benin City. 4. TAKE NOTE: SHORTLY ALL PROPERTIES FOR REGISTRATION WILL TAKE PLACE ON THE EDOGIS WEBSITE: www.edogis.org Signed: Francis Evbuomwan Managing Director Edo State Geographic Information Service EDOGIS HELPLINE: 08136149787, 08156611097 EMAIL: [email protected]; Web: www.edogis.org 1 Advert List 202 11 June, 2021 ESAN NORTH EAST LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA S/N Name(s) File Number Particulars of Plot 1 ERNEST IDEMUDIA EDL 59425 A Parcel of Land at Ward 8, Idume-Obodo Efandion Quarters, Uromi, Edo State transferred from Mr. OTUOKPALUOJIE Otuokpalujie John as shown on survey plan no. KMG/ED/9209/2020 and having an area of 1,088.93m2 and delineated by beacons: AA5294BA, AA5295BA, AA5296BA, AA5297BA and being RESIDENTIAL and UNDEVELOPED. ETSAKO WEST LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA S/N Name(s) File Number Particulars of Plot 2 BELLO-OSOSO ANTHONY EDL 60646 A Parcel of Land at Oba Danesi Village, Edo State transferred from Mr. Braimah S. -

CURRICULUM VITAE of REV. S. A. OJEIFO, Ph.D, FCNA, FCTI, MNIM

CURRICULUM VITAE OF REV. S. A. OJEIFO, Ph.D, FCNA, FCTI, MNIM CURRICULUM VITAE 1. FULL NAME: OJEIFO, Aidelunuoghene Sunday 2. DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: 11th November, 1953 Otuo, Edo State. 3. PLACE AND LOCAL GOVT. OF ORIGIN: Otuo, Owan – East Local Government Area. 4. STATE OF ORIGIN: Edo 5. NATIONALITY: Nigerian 6. MARITAL STATUS: Married 7. NUMBER OF CHILDREN AND THEIR AGES: Five – 34, 34, 30, 28 and 20 8. CURRENT POSTAL ADDRESS: Rev. S.A. Ojeifo, P.O. Box 372, Ekpoma, Edo State. 9. E-MAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] 10. PERMANENT HOME ADDRESS: Chief Ojeifo Odiegua’s Compound, UzawaQuarters, Iyeu-Otuo, Otuo, Edo State. 11. EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS ATTENDED WITH DATES: (i) Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma (2003-2009) (ii) Edo State University, Ekpoma (1997-2000) (iii) Edo State University, Ekpoma (1992-1996) (iv) University of Nigeria, Nsukka, (1990-1991) (v) Auchi Polytechnic, Auchi (1978-1980) (vi) Auchi Polytechnic, Auchi (1974-1976) (vii) Anglican Grammar School, Otuo (1969-1972) 13. ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS OBTAINED WITH DATES AND GRANTING BODIES: A. ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: i. Doctor of Philosophy, (Ph.D) 2009, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma. ii. Masters in Business Administration (MBA) 2000, Edo State University, Ekpoma. iii. Masters of Science (M.Sc), Public Administration, 1996, Edo State University, Ekpoma. iv. The Association of National Accountants of Nigeria (ANAN), 1994. v. Post-Graduate Diploma (Business Administration), 1991, University of Nigeria Nsukka. 1 vi. Higher National Diploma (Accounting), 1980, Auchi Polytechnic, Auchi.. vii. Ordinary National Diploma (Accounting), 1976, Auchi Polytechnic, Auchi. viii. West African School Certificate, 1972, West African Examinations Council. B. -

Y2017-Approved-Capital-Budget.Pdf

OPTION C: BASED ON SECTORS EDO STATE OF NIGERIA 2017 CONSOLIDATED APPROVED BUDGET SUMMARY (MASTER BUDGET) % OF APPROVED REVISED ACTUAL APPROVED % OF APPROVED APPROVED REVISED APPROVED BUDGET S/No Details PROVISION PERFORMANCE PROVISION PROVISION PROVISION REVISED PERF. JAN - NOV JAN - NOV PROVISION 2017 2017 2016 2016 2016 2016 2016 ₦ % ₦ % ₦ ₦ % 1 Opening Balance 10,500,000,000.00 8.19% 1,356,270,122.00 1.69% 1,243,247,611.83 6,332,367,026.18 0% 2 Receipts: - 3 Statutory Allocation: - 4 Edo State Government Share of Statutory Allocation 47,803,650,302.39 37.29% 41,196,570,595.00 51.27% 37,763,523,045.42 24,260,568,289.56 64.24% 5 Edo State Government Share of VAT 9,500,000,000.00 7.41% 8,420,704,384.00 10.48% 7,718,979,018.67 8,054,048,092.00 104.34% 6 Edo State Government Share of Excess Crude - 0.00% 382,725,021.00 0.48% 350,831,269.25 1,819,438,405.04 518.61% 7 Independent Revenue (IGR) 33,826,452,033.39 26.39% 25,000,000,000.00 31.11% 22,916,666,666.67 19,555,485,813.95 85.33% 8 Aids & Grants 24,557,101,943.00 19.16% 4,000,000,000.00 4.98% 3,666,666,666.67 7,500,000,000.00 204.55% 9 Capital Development Fund (CDF) Receipts 2,000,000,000.00 1.56% 0.00% - - 10 Total Current Year Receipts 128,187,204,278.78 100.00% 80,356,270,122.00 100.00% 73,659,914,278.50 67,521,907,626.73 91.67% 11 Total Projected Funds Available 128,187,204,278.78 80,356,270,122.00 xxx 73,659,914,278.50 67,521,907,626.73 91.67% 12 Expenditure: 13 A: Recurrent Debt 14 CRF Charges - Public Debt Charges xx xx xx xx xx xx xx 15 Financial Charges -General 15,899,896,146.00 -

World Bank Document

SFG2386 V3 Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) DRAFT REPORT For PUBLIC WORKS ACTIVITIES ROAD MAINTENANCE ACROSS THE THREE SENATORIAL DISTRICTS OF Public Disclosure Authorized EDO STATE (LOTS 64-108) By Edo SEEFOR SPCU Edo State Employment and Expenditure for Results Project (SEEFOR) EDO STATE GOVERNMENT Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF BUDGET, PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized i THE WORLD BANK ASSISTED PROJECT MAY, 2017. ii Table of Contents Content Page Title Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables iv List of Plates iv List of Maps iv List of figures iv List Boxes iv List of Appendices iv List of Abbreviations and Acronyms vi Executive Summary vii Chapter One: INTRODUCTION AND DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED ACTIVITIES 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 The Proposed Intervention Work 2 1.3 Rational for ESMP for the Proposed Intervention Work 2 1.4 Objectives of this Environmental and Social Management Plan 3 1.5 Scope and Terms of Reference of the ESMP and Tasks 3 1.6 Approaches for Preparing the Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) 4 1.6.1 Literature Review 4 1.6.2 Interactive Discussions/Consultations 4 1.6.3 Identification of Potential Impacts and Mitigation Measures 4 Chapter Two: Institutional and Legal Framework for Environmental 5 2.1 Introduction 5 2.2 World Bank Safeguards Policies Triggered by SEEFOR and the Proposed Activity 5 2.3 Relevant Local and Federal Policy, Legal, Regulatory and Administrative 5 Frameworks 5 2.3.1 State Legislations 5 2.4 Making