Race and the Changing Culture of the NBA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American History at Penn State

Penn State University African American Chronicles February 2010 Table of Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 Years 1899 – 1939 3 Years 1940 – 1949 8 Years 1950 – 1959 13 Years 1960 – 1969 18 Years 1970 – 1979 26 Years 1980 – 1989 35 Years 1990 – 1999 43 Years 2000 – 2008 47 Appendix A – Douglass Association Petition (1967) 56 Appendix B - Douglass Association 12 Demands (1968) 57 Appendix C - African American Student Government Presidents 58 Appendix D - African American Board of Trustee Members 59 Appendix E - First African American Athletes by Sport 60 Appendix F - Black Student Enrollment Chart 61 Appendix G – Davage Report on Racial Discrimination(1958) 62 Appendix H - “It Is Upon Us” Holiday Poem (1939) 63 Penn State University African American Chronicles February 2010 INTRODUCTION “Armed with a knowledge of our past, we can with confidence charter a course for our future.” - Malcolm X Sankofa (sang-ko-fah) is an Akan (Ghana & Ivory Coast) term that literally means, "To go back and get it." One of the symbols for Sankofa (above right) depicts a mythical bird moving forward, but with its head turned backward. The egg in its mouth represents the "gems" or knowledge of the past upon which wisdom is based; it also signifies the generation to come that would benefit from that wisdom. It is hoped that this document will inspire Penn State students, faculty, staff, and alumni to learn from and build on the efforts of those who came before them. Source: Center for Teaching & learning - www.ctl.du.edu In late August, 1979, my twin brother, Darnell and I arrived at Penn State’s University Park campus to begin our college education. -

Comprehension Builders Research Reveals That the Single Most Valuable Activity for Developing Students’ Com- Prehension Is Reading Itself

Daily Comprehension Builders Research reveals that the single most valuable activity for developing students’ com- prehension is reading itself. At its core, comprehension is an active process in which students think about text and gain meaning from it. In order for them to build compe- tence in comprehension, their reading should be purposeful and reflective. It should foster the exploration of genre, language, and information. Daily Comprehension Build- ers is a resource that provides the instructional framework to help your students build strength in comprehension and achieve success in reading! Comprehension Basics Comprehension begins with what a student knows about a topic. It builds as a child reads and actively makes connections between new information and prior knowledge. Understanding is increased as the student organizes what he has read in relationship to what he already knows. To successfully comprehend, students need to master a variety of critical skills, such as constructing word meanings from context, determin- ing main ideas and locating details to support them, sequencing, inferring and drawing conclusions, making generalizations, predicting, summarizing, and sensing an author’s purpose. Daily Comprehension Builders provides multiple opportunities for reinforcing these essential skills, resulting in increased learning and competence in reading. About This Book Thirty-six high-interest reading selections, each accompanied by five activities and two to three reproducible skill sheets, are featured in this book. (See the unit features detailed below.) Each unit is clearly organized and highlights one of the following topics or genres: sports, famous people, animals, oddities, real-life mysteries, and adventure. Use each unit in its entirety, or pick and choose activities to build specific skills. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

2019-20 Panini Flawless Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals 281 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only **Totals do not include 2018/19 Extra Autographs TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 177 177 177 Aaron Gordon 141 141 141 Aaron Holiday 112 112 112 Admiral Schofield 77 77 77 Adrian Dantley 115 115 59 56 Al Horford 385 386 177 169 39 1 Alex English 177 177 177 Allan Houston 236 236 236 Allen Iverson 332 387 295 1 36 55 Allonzo Trier 286 286 118 168 Alonzo Mourning 60 60 60 Alvan Adams 177 177 177 Andre Drummond 90 90 90 Andrea Bargnani 177 177 177 Andrew Wiggins 484 485 118 225 141 1 Anfernee Hardaway 9 9 9 Anthony Davis 453 610 118 284 51 157 Arvydas Sabonis 59 59 59 Avery Bradley 118 118 118 B.J. Armstrong 177 177 177 Bam Adebayo 92 92 92 Ben Simmons 103 132 103 29 Bill Bradley 9 9 9 Bill Russell 186 213 177 9 27 Bill Walton 59 59 59 Blake Griffin 90 90 90 Bob McAdoo 177 177 177 Bobby Portis 118 118 118 Bogdan Bogdanovic 230 230 118 112 Bojan Bogdanovic 90 90 90 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bradley Beal 93 95 93 2 Brandon Clarke 324 434 59 226 39 110 Brandon Ingram 39 39 39 Brook Lopez 286 286 118 168 Buddy Hield 90 90 90 Calvin Murphy 236 236 236 Cam Reddish 380 537 59 228 93 157 Cameron Johnson 290 291 225 65 1 Carmelo Anthony 39 39 39 Caron Butler 1 2 1 1 Charles Barkley 493 657 236 170 87 164 Charles Oakley 177 177 177 Chauncey Billups 177 177 177 Chris Bosh 1 2 1 1 Chris Kaman -

Reginald Howard

20080618_Howard Page 1 of 14 Dara Chesnutt, Denzel Young, Reginald Howard Dara Chesnutt: Appreciate it. Could you start by saying your full name and occupation? Reginald Howard: Reginald R. Howard. I’m a real estate broker and real estate appraiser. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. Where were you born and raised? Reginald Howard: South Bend, Indiana, raised in Indiana, also, born and raised in South Bend. Dara: Where did you grow up and did you move at all or did you stay mostly in –? Reginald Howard: No. I stayed mostly in Indiana. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. What are the names of your parents and their occupations? Reginald Howard: My mother was a housewife and she worked for my father. My father’s name was Adolph and he was a tailor and he had a dry cleaners, so we grew up sorta privileged little black kids. Even though we didn’t have money, people thought we did for some reason. Dara Chesnutt: Did you have any brothers or sisters? Reginald Howard: Sure. Dara Chesnutt: Okay, what are their names and occupations? Reginald Howard: I had a brother named Carlton, who is deceased. [00:01:01] I have a brother named Dean, who’s my youngest brother, who’s just retired from teaching in Tucson, Arizona and I have a sister named Alfreda who’s retired and lives in South Bend still. Dara Chesnutt: Okay. Could you talk a little bit about what your home life was like? Reginald Howard: I don’t know. I had a very strong father and very knowledgeable father. We were raised in a predominantly Hungarian-Polish neighborhood and he – again, he had a business and during that era, it was the area of neighborhood concept businesses and so people came to us for service, came to him for the service, and he was well thought of. -

Jedi of the Jumper Could Teach Lebron Scott Ostler San Francisco Chronicle

3/31/2021 `Awakening' leads to shooting clinics The Wayback Machine - https://web.archive.org/web/20140529055010/http://www.swish22.com:80… Close Window Jedi of the jumper could teach LeBron Scott Ostler San Francisco Chronicle Thursday, Oct. 23, 2003 The Johnny Appleseed of jump shots is on the road as we speak, spreading his simple gift to the world, even if the world isn't always ready to receive. Take LeBron James, for instance. A recent discovery has been made about James, the NBA's teen wonder who recently graduated high school. He can't shoot. On mid-range jump shots, James has the deft touch of a grizzly bear trained to repair watches with a mallet. Man, would the Johnny Appleseed of jump shots -- his name is Tom Nordland -- love to get his hands on LeBron. Explain to him why he shouldn't be cranking the ball so far back, waiting until the top of his jump to release the ball. Show him how he is greatly complicating one of nature's simplest movements. It pains Nordland to watch most NBA guys shoot. The pure jump shot is a lost art, like cave painting. It's been pushed aside by the power game, lack of good shot coaching, apathy. Baseball pitchers and hitters continually tinker with their form. Most NBA guys work on their facial hair more than they work on improving their jumper. A few NBA players have a pure stroke, Nordland says. Dirk Nowitzki, Steve Nash. Doug Christie and Mike Bibby, at times. But to watch what Chris Webber tries to pass off as a jumper, or to ponder Erick Dampier's release point, is horrifying. -

2006 Media Guide.Indd

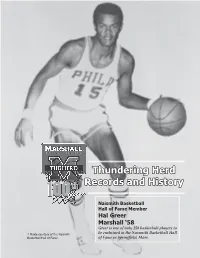

TThunderinghundering HerdHerd RRecordsecords aandnd HHistoryistory Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame Member Hal Greer Marshall ‘58 Greer is one of only 258 basketball players to * Photo courtesy of the Naismith be enshrined in the Naismith Basketball Hall Basketball Hall of Fame. of Fame in Springfi eld, Mass. 9977 r “Consistency,” Hal Hal Greer was named one of the NBA’s Top e Greer once told the e 50 Players in the late 90’s. He averaged 19 r Philadelphia Daily points, fi ve rebounds, and four assists in his G News. “For me, that was l NBA career. a the thing … I would like H Hal Greer to be remembered as a great, consistent player.” Over the course of rebounds and 4.4 assists per contest. With injuries limiting the 15 NBA seasons Schayes to 56 games, Greer took over the team’s scoring turned in by the slight, mantle. He ranked 13th in the NBA in scoring and ninth soft -spoken Hall of in free-throw percentage (.819). In the 1962 NBA All-Star Fame guard from West Game, Greer racked up a team-high nine assists - one more Virginia, consistency than the legendary Bob Cousy - and hauled in 10 rebounds, was indeed the thing. just two fewer than another legend, Bill Russell. Greer led He turned in quality the Nationals to the playoff s, where they fell to Warriors in performances almost every night, scoring 19.2 points the Eastern Division Semifi nals. per game during his career, playing in 1,122 games, and The smooth guard broke into the ranks of the top 10 racking up 21,586 points (14th on the all-time list). -

Class of 2018

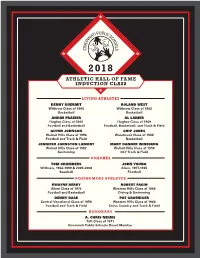

2018 ATHLETIC Hall OF FaME INDUCTION ClaSS LIVING ATHLETES DENNY DUERMIT ROLAND WEST Withrow Class of 1969 Withrow Class of 1962 Basketball Basketball ANDRE FRAZIER AL LaNIER Hughes Class of 2000 Hughes Class of 1969 Football and Basketball Football, Basketball, and Track & Field GLYNN JOHNSON CHIP JONES Walnut Hills Class of 1996 Woodward Class of 1988 Football and Track & Field Basketball JENNIFER JOHNSTON LaMONT MaRY DANNER WINEBERG Walnut Hills Class of 1982 Walnut Hills Class of 1998 Swimming OLY Track & Field COACHES TOM CHAMBERS JOHN YOUNG Withrow, 1966-1999 & 2005-2008 Aiken, 1977-1985 Baseball Football POSTHUMOUS ATHLETES DwaYNE BERRY ROBERT FagIN Aiken Class of 1975 Western Hills Class of 1946 Football and Basketball Diving & Swimming DENNY DASE PaT GROENIGER Central Vocational Class of 1959 Western Hills Class of 1946 Football and Track & Field Cross Country and Track & Field HONORARY A. CHRIS NELMS Taft Class of 1971 Cincinnati Public Schools Board Member WELCOME TO THE 2018 CPS ATHLETIC HALL OF FAME INDUCTION CEREMONY HOSTED BY PRESENTED BY THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 2018 SOCIal HOUR: 5PM | WELCOME AND DINNER: 6PM INDUCTION CEREMONY: 7PM MASTERS OF CEREMONY John Popovich, Sports Director WCPO Channel 9 Lincoln Ware, SOUL 101.5 COAch INDucTEES Tom Chambers, Withrow High School John Young, Aiken High School POSThumOUS INDucTEES Dwayne Berry, Aiken High School Denny Dase, Central Vocational High School Robert Fagin, Western Hills High School Pat Groeniger, Western Hills High School Livi2018NG AThlETE INDucTEES Denny Duermit, Withrow High School Andre Frazier, Hughes High School Glynn Johnson, Walnut Hills High School Jennifer Johnston LaMont, Walnut Hills High School Roland West, Withrow High School Chip Jones, Woodward High School Al Lanier, Hughes High School Mary Danner Wineberg, Walnut Hills High School HONORARY INDucTEE A. -

Other Basketball Leagues

OTHER BASKETBALL LEAGUES {Appendix 2.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of August 1, 2012 AMERICAN BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION (ABA) LEAGUE UPDATE: For the 2011-12 season, the following teams are no longer members of the ABA: Atlanta Experience, Chi-Town Bulldogs, Columbus Riverballers, East Kentucky Energy, Eastonville Aces, Flint Fire, Hartland Heat, Indiana Diesels, Lake Michigan Admirals, Lansing Law, Louisiana United, Midwest Flames Peoria, Mobile Bat Hurricanes, Norfolk Sharks, North Texas Fresh, Northwestern Indiana Magical Stars, Nova Wonders, Orlando Kings, Panama City Dream, Rochester Razorsharks, Savannah Storm, St. Louis Pioneers, Syracuse Shockwave. Team: ABA-Canada Revolution Principal Owner: LTD Sports Inc. Team Website Arena: Home games will be hosted throughout Ontario, Canada. Team: Aberdeen Attack Principal Owner: Marcus Robinson, Hub City Sports LLC Team Website: N/A Arena: TBA © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Alaska 49ers Principal Owner: Robert Harris Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School UPDATE: Due to the success of the Alaska Quake in the 2011-12 season, the ABA announced plans to add another team in Alaska. The Alaska 49ers will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012-13 season. The 49ers will compete in the Pacific Northwest Division. Team: Alaska Quake Principal Owner: Shana Harris and Carol Taylor Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School Team: Albany Shockwave Principal Owner: Christopher Pike Team Website Arena: Albany Civic Center Facility Website UPDATE: The Albany Shockwave will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012- 13 season. -

Bill Russell to Speak at University of Montana December 3

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 11-25-1969 Bill Russell to speak at University of Montana December 3 University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "Bill Russell to speak at University of Montana December 3" (1969). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 5342. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/5342 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMEDIATELY $ 13 O r t S herrin/js ____ ___ ___________________________ 11/ 25/69 state + cs Information Services • University of montana • missoula, montana 59801 • (406) 243-2522 BILL RUSSELL TO SPEAK AT UM DEC. 3 MISSOULA-- Bill Russell, star basketball player-coach for the Boston Celtics, will speak at the University of Montana Dec. 3. Russell, the first Negro to manage full-time in a major league of any sport, will lecture in the University Center Ballroom at 8:15 p.m. Dec. 3. His appearance, which is open to the public without charge, is sponsored by the Program Council of the Associated Students at UM. Russell's interests are not confined to the basketball court. -

Ucla Men's Basketball

UCLA MEN’S BASKETBALL March 25, 2006 Bill Bennett/Marc Dellins /310-206-7870 For Immediate Release UCLA Men’s Basketball/NCAA Between Game Notes NO. 7 UCLA PLAYS NO. 4 MEMPHIS IN NCAA REGIONAL FINAL IN OAKLAND ON SATURDAY, WINNER ADVANCES TO “FINAL FOUR” IN INDIANAPOLIS; BRUINS EDGE GONZAGA 73-71 ON THURSDAY IN “SWEET 16” CONTEST No. 7/No. 8 UCLA (30-6/Pac-10 14-4, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 2 Seed) vs. No. 4/No. 3 MEMPHIS (33-3/Conference USA 13-1, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 1 Seed) - Saturday, March 25/Oakland, CA/Oakland Arena/4:05 p.m. PT/TV- CBS, Gus Johnson and Len Elmore/Radio-570AM, with Chris Roberts and Don MacLean. Tentative UCLA Starters F- 21 Cedric Bozeman 6-6, Sr., 7.8, 3.2 F-23 Luc Richard Mbah a Moute 6-8, Fr., 9.1, 8.1 C- 15 Ryan Hollins 7-01/2, Sr., 6.7, 4.5 G-1 Jordan Farmar 6-2, So., 13.6, 2.5 G-4 Arron Afflalo 6-4, So., 16.2, 4.3 UCLA vs. Memphis – The Tigers advanced with an 80-64 victory over Bradley, led by Rodney Carney’s 23 points. Memphis has won 22 of its last 23 games and has a seven-game winning streak. This will be the team’s second meeting this season – on Nov. 23 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, Memphis defeated UCLA 88-80 in an NIT Season Tip-Off semifinal. Last Meeting - Nov. 23 – No. 11 Memphis 88, No. -

Downtrodden Yet Determined: Exploring the History Of

DOWNTRODDEN YET DETERMINED: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF BLACK MALES IN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL AND HOW THE PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ADDRESSES THEIR WELFARE A Dissertation by JUSTIN RYAN GARNER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, John N. Singer Committee Members, Natasha Brison Paul J. Batista Tommy J. Curry Head of Department, Melinda Sheffield-Moore May 2019 Major Subject: Kinesiology Copyright 2019 Justin R. Garner ABSTRACT Professional athletes are paid for their labor and it is often believed they have a weaker argument of exploitation. However, labor disputes in professional sports suggest athletes do not always receive fair compensation for their contributions to league and team success. Any professional athlete, regardless of their race, may claim to endure unjust wages relative to their fellow athlete peers, yet Black professional athletes’ history of exploitation inspires greater concerns. The purpose of this study was twofold: 1) to explore and trace the historical development of basketball in the United States (US) and the critical role Black males played in its growth and commercial development, and 2) to illuminate the perspectives and experiences of Black male professional basketball players concerning the role the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA), collectively considered as the Players Association for this study, played in their welfare and addressing issues of exploitation. While drawing from the conceptual framework of anti-colonial thought, an exploratory case study was employed in which in-depth interviews were conducted with a list of Black male professional basketball players who are members of the Players Association.