The New Road to Serfdom: the Curse of Bigness and the Failure of Antitrust, 49 U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Court Review: the Journal of the American Judges Association American Judges Association

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Court Review: The Journal of the American Judges Association American Judges Association 2015 Court Review: The Journal of the American Judges Association 51:3 (2015)- Whole Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ajacourtreview "Court Review: The Journal of the American Judges Association 51:3 (2015)- Whole Issue" (2015). Court Review: The Journal of the American Judges Association. 526. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ajacourtreview/526 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the American Judges Association at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Review: The Journal of the American Judges Association by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Court ReviewVolume 51, Issue 3 THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN JUDGES ASSOCIATION TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORS BOOK REVIEW Judge Steve Leben Kansas Court of Appeals 90 Writing Like the Best Judges Professor Eve Brank Steve Leben University of Nebraska MANAGING EDITOR Charles F. Campbell National Center for State Courts ARTICLES ASSOCIATE EDITOR Justine Greve 94 Weddings, Whiter Teeth, Judicial-Campaign Speech, and More: Kansas Court of Appeals Civil Cases in the Supreme Court’s 2014-2015 Term EDITORIAL BOARD Todd E. Pettys Kelly Lynn Anders Kansas City, Missouri 106 Making Continuous Improvement a Reality: Judge Karen Arnold-Burger Kansas Court of Appeals Achieving High Performance in the Ottawa County, Michigan, Circuit and Probate Courts Pamela Casey, Ph.D. Brian J. Ostrom, Matthew Kleiman, Shannon Roth & Alicia Davis National Center for State Courts Judge B. -

Reliability and Security of Large Scale Data Storage in Cloud Computing C.W

This article is part of the Reliability Society 2010 Annual Technical Report Reliability and Security of Large Scale Data Storage in Cloud Computing C.W. Hsu ¹¹¹ C.W. Wang ²²² Shiuhpyng Shieh ³³³ Department of Computer Science Taiwan Information Security Center at National Chiao Tung University NCTU (TWISC@NCTU) Email: ¹[email protected] ³[email protected] ²[email protected] Abstract In this article, we will present new challenges to the large scale cloud computing, namely reliability and security. Recent progress in the research area will be briefly reviewed. It has been proved that it is impossible to satisfy consistency, availability, and partitioned-tolerance simultaneously. Tradeoff becomes crucial among these factors to choose a suitable data access model for a distributed storage system. In this article, new security issues will be addressed and potential solutions will be discussed. Introduction “Cloud Computing ”, a novel computing model for large-scale application, has attracted much attention from both academic and industry. Since 2006, Google Inc. Chief Executive Eric Schmidt introduced the term into industry, and related research had been carried out in recent years. Cloud computing provides scalable deployment and fine-grained management of services through efficient resource sharing mechanism (most of them are for hardware resources, such as VM). Convinced by the manner called “ pay-as-you-go ” [1][2], companies can lower the cost of equipment management including machine purchasing, human maintenance, data backup, etc. Many cloud services rapidly appear on the Internet, such as Amazon’s EC2, Microsoft’s Azure, Google’s Gmail, Facebook, and so on. However, the well-known definition of the term “Cloud Computing ” was first given by Prof. -

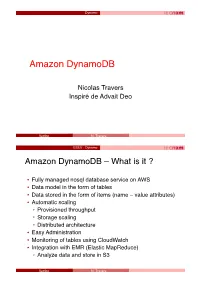

Amazon Dynamodb

Dynamo Amazon DynamoDB Nicolas Travers Inspiré de Advait Deo Vertigo N. Travers ESILV : Dynamo Amazon DynamoDB – What is it ? • Fully managed nosql database service on AWS • Data model in the form of tables • Data stored in the form of items (name – value attributes) • Automatic scaling ▫ Provisioned throughput ▫ Storage scaling ▫ Distributed architecture • Easy Administration • Monitoring of tables using CloudWatch • Integration with EMR (Elastic MapReduce) ▫ Analyze data and store in S3 Vertigo N. Travers ESILV : Dynamo Amazon DynamoDB – What is it ? key=value key=value key=value key=value Table Item (64KB max) Attributes • Primary key (mandatory for every table) ▫ Hash or Hash + Range • Data model in the form of tables • Data stored in the form of items (name – value attributes) • Secondary Indexes for improved performance ▫ Local secondary index ▫ Global secondary index • Scalar data type (number, string etc) or multi-valued data type (sets) Vertigo N. Travers ESILV : Dynamo DynamoDB Architecture • True distributed architecture • Data is spread across hundreds of servers called storage nodes • Hundreds of servers form a cluster in the form of a “ring” • Client application can connect using one of the two approaches ▫ Routing using a load balancer ▫ Client-library that reflects Dynamo’s partitioning scheme and can determine the storage host to connect • Advantage of load balancer – no need for dynamo specific code in client application • Advantage of client-library – saves 1 network hop to load balancer • Synchronous replication is not achievable for high availability and scalability requirement at amazon • DynamoDB is designed to be “always writable” storage solution • Allows multiple versions of data on multiple storage nodes • Conflict resolution happens while reads and NOT during writes ▫ Syntactic conflict resolution ▫ Symantec conflict resolution Vertigo N. -

Report of the Council to the Membership of the American Law Institute on the Matter of the Death Penalty

Submitted by the Council to the Members of The American Law Institute for Consideration at the Eighty-Sixth Annual Meeting on May 19, 2009 Report of the Council to the Membership of The American Law Institute On the Matter of the Death Penalty (April 15, 2009) The Executive Office The American Law Institute 4025 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-3099 Telephone: (215) 243-1600 • Fax: (215 243-1636 Email: [email protected] • Website: http://www.ali.org The American Law Institute Michael Traynor, Chair of the Council and President Emeritus Roberta Cooper Ramo, President Allen D. Black, 1st Vice President Douglas Laycock, 2nd Vice President Bennett Boskey, Treasurer Susan Frelich Appleton, Secretary Lance Liebman, Director Elena A. Cappella, Deputy Director COUNCIL Kenneth S. Abraham, University of Virginia School of Law, Charlottesville, VA Shirley S. Abrahamson, Supreme Court of Wisconsin, Madison, WI Philip S. Anderson, Williams & Anderson, Little Rock, AR Susan Frelich Appleton, Washington University School of Law, St. Louis, MO Kim J. Askew, K&L Gates, Dallas, TX José I. Astigarraga, Astigarraga Davis, Miami, FL Sheila L. Birnbaum, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, New York, NY Allen D. Black, Fine, Kaplan & Black, Philadelphia, PA Bennett Boskey, Washington, DC Amelia H. Boss, Drexel University Earle Mack School of Law, Philadelphia, PA Michael Boudin, U.S. Court of Appeals, First Circuit, Boston, MA William M. Burke, Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton, Costa Mesa, CA Elizabeth J. Cabraser, Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein, San Francisco, CA Gerhard Casper, Stanford University, Stanford, CA Edward H. Cooper, University of Michigan Law School, Ann Arbor, MI N. Lee Cooper, Maynard, Cooper & Gale, Birmingham, AL George H. -

Giants: the Global Power Elite

Secrecy and Society ISSN: 2377-6188 Volume 2 Number 2 Teaching Secrecy Article 13 January 2021 Giants: The Global Power Elite Susan Maret San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Other Sociology Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public olicyP and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Maret, Susan. 2021. "Giants: The Global Power Elite." Secrecy and Society 2(2). https://doi.org/10.31979/2377-6188.2021.020213 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/ secrecyandsociety/vol2/iss2/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Secrecy and Society by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Giants: The Global Power Elite Keywords human rights, C. Wright Mills, openness, power elite, secrecy, transnational corporations, transparency This book review is available in Secrecy and Society: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/ secrecyandsociety/vol2/iss2/13 Maret: Giants: The Global Power Elite Review, Giants: The Global Power Elite by Peter Philips Reviewed by Susan Maret Giants: The Global Power Elite, New York: Seven Stories Press, 2018. 384pp. / ISBN: 9781609808716 (paperback) / ISBN: 9781609808723 (ebook) https://www.sevenstories.com/books/4097-giants The strength of Giants: The Global Power Elite lies in its heavy documentation of the "globalized power elite, [a] concept of the Transnationalist Capitalist Class (TCC), theorized in the academic literature for some twenty years" (Phillips 2018, 9). -

Concessions and How to Beat Them

a Labor Notes Book 0 ESSID 4, ad owto beat them by Jane Slaughter With a Foreword by William W. Winpisinger President, International Association of Machinists ONCE SIONS and how to beat them_____ by Jane Slaughter Labor Education & Research Project Publishers of Labor Notes Detroit Copyright © 1983 by the Labor Education & Research Project Any short, attributed quotation may be used without permission. First printing July 1983 Second printing June 1985 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 83-81803 ISBN: 0-914093-03-7 Published by the Labor Education & Research Project Designed by David McCullough 138 This book is dedicated to the members of the United Mine Workers of America, who struck against concessions in 1978, before concessions had a name. CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..........~....... vi Foreword 1 ~ntroduction 5 IFromMoretoLess 10 2 The Economics Behind Concessions. .43 3 Why Concessions Don’t Work 52 4 Resisting Concessions 66 5 An Offensive Strategy for the Labor Movement 108 GResources 125 Appendix A Union Education on Concessions . 143 Appendix B ModelLanguage on Investment. 145 Notes 147 There is a list of union abbreviations on pages 14-15 _______Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the many people who contributed information for this book or who commented on various drafts: James Bialke, Geoff Bickerton, Dave Blitzstein, Jon Brandow, Rick Braswell, Kate Bronfenbrenner, Nick Builder, Mike Cannon, Bill Carey, Dorsey Cheuvront, Elissa Clarke, Carole Coplea, Alice Dale, Gerry Deneau, Wayne Draznin, Enid Eckstein, Larry -

Plane Hits Carrier: Fire Kills 14

2 i - THE HERALD, Tues , May 26. 1981 r Graduation ceremonies highlight weekend hung antiwar banners from their By SUZANNE TRIMEL reaffirmed the threat of Soviet in nation’s capitoi or in Rome is an act Education Secretary Shirley academic gowns. light history of the nation's recent United P r e s s tervention in the Third World in a of aggression against all of us?” Hufstedler, Harvard statistician A solemn procession of 4,450 political fortunes ... speech on a pastoral hill. DiBiaggio asked. page 24 Frederick Mosteller and author Elie International University of Connecticut graduates Fairfield also gave honorary Patricia Wald, U.S. Circuit Court Wiesel. "A leading man and a cast in — some carrying a single rose — Graduates attached pine sprigs degrees to the Rev. Bruce Ritter, a Judge for Washington, D.C., told Two sisters and their brother cluding half the lawyers in Califor and balloons to their mortarboards broke into dancing, shrieking and Franciscan who founded a home for Connecticut College graduates in were among just over 3,000 students nia moved to Washington,” she hugging as diplomas were handed — danced, shrieked and hugged one runaway teen-agers in New 'York's New London the nation faced a receiving Yale degrees. quipped. “ A number of ^uthemers oul in Storrs another — as nearly 10,000 diplomas Times ^uare, and the Rev. Joseph severe test — preserving democracy Christine Wallich earned a doc went home again — Thomas Wolfe were handed out in Connecticut this At Fairfield Uhiversity, 22 Fitzmyer, a Jesuit authority on "in an era of big money, intrusive torate, her sister, Anna Wallich notwithstanding.” weekend with a concert violinist and professors staged a walkout and Biblical language and literature. -

13Th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Going Viral 2021

2021 13th International Conference on Cyber Confict: Going Viral T. Jančárková, L. Lindström, G. Visky, P. Zotz (Eds.) 2021 13TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CYBER CONFLICT: GOING VIRAL Copyright © 2021 by NATO CCDCOE Publications. All rights reserved. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP2126N-PRT ISBN (print): 978-9916-9565-4-0 ISBN (pdf): 978-9916-9565-5-7 COPYRIGHT AND REPRINT PERMISSIONS No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence ([email protected]). This restriction does not apply to making digital or hard copies of this publication for internal use within NATO, or for personal or educational use when for non-proft or non-commercial purposes, providing that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the frst page as follows: [Article author(s)], [full article title] 2021 13th International Conference on Cyber Confict: Going Viral T. Jančárková, L. Lindström, G. Visky, P. Zotz (Eds.) 2021 © NATO CCDCOE Publications NATO CCDCOE Publications LEGAL NOTICE: This publication contains the opinions of the respective authors only. They do not Filtri tee 12, 10132 Tallinn, Estonia necessarily refect the policy or the opinion of NATO Phone: +372 717 6800 CCDCOE, NATO, or any agency or any government. NATO CCDCOE may not be held responsible for Fax: +372 717 6308 any loss or harm arising from the use of information E-mail: [email protected] contained in this book and is not responsible for the Web: www.ccdcoe.org content of the external sources, including external websites referenced in this publication. -

Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies Edward A

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2016 Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies Edward A. Purcell New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation 64 Buff. L. Rev. 23 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies EDWARD A. PURCELL, JR.t INTRODUCTION Politically charged claims about both "capitalism" and "risk" became increasingly insistent in the late twentieth century. The end of the post-World War II boom in the 1970s and the subsequent breakup of the Soviet Union inspired fervent new commitments to capitalist ideas and institutions. At the same time structural changes in the American economy and expanded industrial development across the globe generated sharpening anxieties about the risks that those changes entailed. One result was an outpouring of roseate claims about capitalism and its ability to control those risks, including the use of new techniques of "risk management" to tame financial uncertainties and guarantee stability and prosperity. Despite assurances, however, recent decades have shown many of those claims to be overblown, if not misleading or entirely ill-founded. Thus, the time seems ripe to review some of our most basic economic ideas and, in doing so, reflect on what we might learn from past centuries about the nature of both "capitalism" and "risk," the relationship between the two, and their interactions and consequences in contemporary America. -

2010 in Review from Commerce

Dec. 28, 2010 Invite a Friend [email protected] 2010 in review from Commerce Happy Holidays from all of us at the North Carolina Department of Commerce! As 2010 draws to a close, this week’s SYNC takes a look back at the year's top economic development accomplishments from across North Carolina. Like 2009, 2010 presented difficult challenges to the state’s economic development community, but there were also many success stories and examples of outstanding collaboration in all corners of the state. Established businesses such as Caterpillar, Siemens and IBM continued their commitment to North Carolina by expanding in the state. New partners such as Facebook helped cement North Carolina's reputation as a leader in the data center industry. This year also saw the launch of ThriveNC.com, a new website dedicated to meet the needs of business decision-makers and site selection consultants, as well as an expanded marketing program for in-state partners. Topping it off, Site Selection magazine once again named the state as the nation's best business climate. With continued leadership from Governor Bev Perdue and N.C. Department of Commerce Secretary Keith Crisco, along with the collaborative efforts of every member of the state's economic development community, the outlook for 2011 looks bright. In the coming year, SYNC will continue to bring you the news and information that builds collaborative relationships and helps us all stay in SYNC. Perdue announces small business initiatives Governor Bev Perdue on Jan. 13 announced her major policy priorities for the coming year – jobs and the economy, education, setting government straight, and keeping communities safe. -

Being Lord Grantham: Aristocratic Brand Heritage and the Cunard Transatlantic Crossing

Being Lord Grantham: Aristocratic Brand Heritage and the Cunard Transatlantic Crossing 1 Highclere Castle as Downton Abbey (Photo by Gill Griffin) By Bradford Hudson During the early 1920s, the Earl of Grantham traveled from England to the United States. The British aristocrat would appear as a character witness for his American brother-in-law, who was a defendant in a trial related to the notorious Teapot Dome political scandal. Naturally he chose to travel aboard a British ship operated by the oldest and most prestigious transatlantic steamship company, the Cunard Line. Befitting his privileged status, Lord Grantham was accompanied by a valet from the extensive staff employed at his manor house, who would attend to any personal needs such as handling baggage or assistance with dressing. Aboard the great vessel, which resembled a fine hotel more than a ship, passengers were assigned to accommodations and dining facilities in one of three different classes of service. Ostensibly the level of luxury was determined solely by price, but the class system also reflected a subtle degree of social status. Guests in the upper classes dressed formally for dinner, with men wearing white or black tie and women wearing ball gowns. Those who had served in the military or diplomatic service sometimes wore their medals or other decorations. Passengers enjoyed elaborate menu items such as chateaubriand and oysters Rockefeller, served in formal style by waiters in traditional livery. The décor throughout the vessel resembled a private club in London or an English country manor house, with ubiquitous references to the British monarchy and empire. -

The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Review Volume 2010 | Issue 2 Article 9 5-1-2010 The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Randall D. Guynn, The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform, 2010 BYU L. Rev. 421 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2010/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DO NOT DELETE 4/26/2010 8:05 PM The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn The U.S. real estate bubble that popped in 2007 launched a sort of impersonal chevauchée1 that randomly destroyed trillions of dollars of value for nearly a year. It culminated in a worldwide financial panic during September and October of 2008.2 The most serious recession since the Great Depression followed.3 Central banks and governments throughout the world responded by flooding the markets with money and other liquidity, reducing interest rates, nationalizing or providing extraordinary assistance to major financial institutions, increasing government spending, and taking other creative steps to provide financial assistance to the markets.4 Only recently have markets begun to stabilize, but they remain fragile, like a man balancing on one leg.5 The United States and other governments have responded to the financial crisis by proposing the broadest set of regulatory reforms Partner and Head of the Financial Institutions Group, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, New York, New York.