Appendix a Local Lore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOU Amendment-CJCC SIGNED Combined for Website

MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN LAC COURTE OREILLES BAND OF LAKE SUPERIOR CHIPPEWA INDIANS AND SAWYER COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CONCERNING THE SAWYER COUNTY CRIMINAL JUSTICE COORDINATION COMMITTEE This Memorandum of Understanding ("MOU") is entered into by the Lac Courte Oreilles Tribal Governing Board ("Tribal Governing Board"); the Sawyer County Board of Supervisors ("County Board"). Recitals: The Lac Courte Oreilles Tribal Governing Board serves as the governing body of the Lac CoUite Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians ("Tribe") pursuant to Article III, Section 1 of the Lac Courte Oreilles Constitution and Bylaws, as amended in 1966. The Sawyer County Board of Supervisors serves as the governing body for Sawyer County and is tasked with coordinating necessary services for the residents of Sawyer County, pursuant to the Wisconsin Constitution Article IV, Section 22 and Section 23; See also Wis. Stat. §§59.03 and§§ 59.10 (2)(3) (5). Purpose: The primary purpose of this MOU is to recognize and solidify the relationship between the Tribal Governing Board and the County Board in their eff01ts to assist with the provision of criminal justice services in Sawyer County. The existing criminal justice services in Sawyer County are; the Circuit Court, Tribal Court, County District Attorney's Office, Tribal Legal Department, Sawyer County Sheriffs Department, Tribal Police Department, Department of Corrections as well as Mental Health and Substance Facilitators. The secondary purpose of this MOU is to establish and support a Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee that shall assist the existing criminal justice services provided in Sawyer County by coordinating the services provided so that strategies can be developed to ensure the efficient and effective deployment of both county and tribal resources. -

Lac Courte Oreilles Lake Management Plan

Lac Courte Oreilles Lake Management Plan C. Bruce Wilson February 21, 2011 Acknowledgements I thank WDNR Project Manager Jim Kreitlow for his advice during the project and his document review assistance. I also thank the Courte Oreilles Lakes Association for their support and encouragement, particularly Gary Pulford who has been the grant coordinator, project lead and tireless advocate for Wisconsin lakes and streams. I thank Dan Tyrolt and the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Ojibwe Conservation Department for their support, guidance and data collected over the past 14 years, without which, this report would not have been possible. The Lac Courte Oreilles Tribal Conservation Department’s lake and stream monitoring programs are exceptional. Sawyer County’s technical support, particularly Dale Olson, was greatly appreciated. Lastly, I thank Rob Engelstad and Gary Pulford for Secchi disk volunteer monitoring and all of the residents who participated in the LCO Economic Survey. 1 February 21, 2011 Lac Courte Oreilles Lake Management Plan Report Section Page Executive Summary…………………………………………........................................... 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 8 Outstanding Resource Waters ……………………………………………… 9 Fisheries ……………………………………………………………………… 10 Lac Courte Oreilles Morphometric Characteristics ……………………… 13 Lac Courte Oreilles Watershed Characteristics …………………………… 16 Hydrologic Budget Climatological Summary ………………………………………….... 19 Precipitation …………………………………………………. 20 Temperature and Evaporation …...…………………………. 23 Surface Water -

Nutrient, Trace-Element, and Ecological History of Musky Bay, Lac Courte Oreilles, Wisconsin, As Inferred from Sediment Cores

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Nutrient, Trace-Element, and Ecological History of Musky Bay, Lac Courte Oreilles, Wisconsin, as Inferred from Sediment Cores Water-Resources Investigations Report 02–4225 Study area EXPLANATION WISCONSIN Local drainage basin Open water Wetland Stream Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation Drainage basin boundary Core collected in 1999 Core collected in 2001 Grindstone Lake ek re Windigo C aw Lake u q S Northeastern Bay Chicago Durphee Bay Lake Stucky Bay G host Cre Lac Courte Oreilles ek Little Lac Courte Musky Bay Oreilles age Whitefish Lake Sand Lake Billy Boy FlowFlowage Couderay Ashegon 0 1 2 MILES River Lake Devils 0 1 2 KILOMETERS Lake Prepared in cooperation with the Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection Nutrient, Trace-Element, and Ecological History of Musky Bay, Lac Courte Oreilles, Wisconsin, as Inferred from Sediment Cores By Faith A. Fitzpatrick, Paul J. Garrison, Sharon A. Fitzgerald, and John F. Elder U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02–4225 Prepared in cooperation with the Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection Middleton, Wisconsin 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Government. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. -

Grindstone Lake Fact Sheet

THE GRINDSTONE LAKE AREA GRINDSTONE LAKE LAC COURTE OREILLES RESERVATION • “Grindstone Lake” originates from the Ojibwe • The eastern portion of the Grindstone Lake word Gaa-zhiigwanaabikokaag meaning “a lies within the boundaries of the Lac Courte place abundant with grindstones [or round Oreilles (LCO) Band of Lake Superior sharpening stones used for grinding or Chippewa. sharpening ferrous tools].” It’s also been called “Lac du Gres” which means “Sandstone Lake” • Population: 3,013 (707 are Non-Native in French Americans)-- The LCO Tribe is one of several reservations that has a relatively large • Grindstone Lake is a popular resort area non-Native population within its borders. drawing cabin owners and visitors from the Broken treaty promises allowed settlement by Minneapolis, St. Paul, Milwaukee, and Chicago white squatters and the U.S. allowed them to metropolitan areas stay • 4th largest lake in Sawyer County • The LCO Reservation, located mostly (3,176 acres, 12.85 km^2) in Sawyer County, totals 76,465 acres; approximately 10,500 acres are lakes • 12th deepest in Sawyer County (60 feet) • The LCO casino employs approximately 900 • 39th largest in the state of Wisconsin people—21% (189) are non-Native • 205th deepest in the state of Wisconsin Americans, and 79% (711) are Native Americans • No public beaches • Total tribal enrollment is 7,275 members, • Native species of fish in the lake include of which 60% live in LCO in 23 different musky, panfish, largemouth bass, smallmouth community villages bass, northern pike, walleye, and -

Winter Hydroelectric Dam Feasibility Assessment: the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe

WINTER HYDROELECTRIC DAM FEASIBILITY ASSESSMENT THE LAC COURTE OREILLES BAND OF LAKE SUPERIOR OJIBWE PRESENTED BY JASON WEAVER LAC COURTE OREILLES HISTORY • WE ARE LOCATED IN SAWYER COUNTY IN THE NORTHWESTERN REGION OF WISCONSIN. • WE HAVE 7,310 ENROLLED TRIBAL MEMBERS • THE RESERVATION CONSIST OF 76,465 ACRES, ABOUT 10,500 ACRES ARE WATER • WE HAVE ENTERED 4 SOVEREIGN TREATIES WITH THE U.S. GOVERNMENT. 1825, 1837, 1842 AND THE LA POINTE TREATY OF 1854 WHICH ESTABLISHED THE CURRENT RESERVATIONS AND PRESERVED OUR RIGHT TO HUNT, FISH AND GATHER IN THE NORTHERN REGIONS OF MN, WI AND MI. LCO TRIBAL GOVERNMENT • OUR OFF RESERVATION RIGHTS WERE AGAIN RECOGNIZED AFTER LITIGATION IN THE 1983 LAC COURTE OREILLES V. VOIGHT 700 F 2D 341 (7TH CIRCUIT) • OUR TRIBE HAD TRADITIONAL GOVERNMENT THAT PROVIDED FOR THE WELFARE AND SAFETY OF THE MEMBERS. AFTER YEARS OF RESISTANCE LAC COURTE OREILLES ADOPTED AN INDIAN REORGANIZATION ACT TYPE CONSTITUTION IN 1966 WHICH ESTABLISHED OUR CURRENT TRIBAL GOVERNMENT AND SEVEN MEMBER TRIBAL COUNCIL. • THIS CONSTITUTION ESTABLISHED OUR SOVEREIGN JURISDICTION, TRIBAL COURT, ORDINANCES, CONTRACTS, GOVERNMENTAL NEGOTIATIONS, BUSINESS AND HOUSING THAT WERE HARD TO ATTAIN FUNDING FOR WITHOUT A CONSTITUTION. LAC COURTE OREILLES • THE LAC COURTE OREILLES BAND OF LAKE SUPERIOR OJIBWE HAVE BEEN LOCATED IN WHAT IS NOW CALLED WISCONSIN FOR HUNDREDS OF YEARS. THE LOCATION WHERE THE DAM WAS BUILT IS CALLED PAH QUAH WONG WHICH MEANS “WHERE THE RIVER IS WIDE” IT WAS FORCED UPON MY TRIBE IN 1920. OVER 5000 ACRES OF RESOURCEFUL, RIVERS, LAKES, LANDS AND MANY HOMES WERE FLOODED BY NORTHERN STATES POWER. -

Fishing-2019-2020.Pdf

Hayward Area Lake Information Northern Crappie & Musky Walleye Bass LAKES Acres Depth Pike Bluegill Barker Lake 238 12’ A2 X X X Big Sissabagama 619 48’ A2 X X X Big Stone Lake 523 49’ X X X X Blueberry Lake 280 29’ X X X Callahan Lake/Mud Lake 480 18’ A2 X X X Chippewa Flowage 15,300 82’ A1 X X X Eau Claire Lakes Chain 2,704 92’ A1 X X X X Ghost Lake 372 12’ A2 X X X X Grindstone Lake 3,110 59’ A1 X X X X Hayward Lake 247 17’ A2 X X X X Lac Courte Oreilles 5,038 90’ A1 X X X X Lake Chetac 2,100 30’ X X X X Lake Namakagon 3,208 51’ A1 X X X X Lake Owen 1,250 95’ X X X X Little Lac Courte Oreilles 240 46’ A1 X X X X Little Round Lake 243 38’ A1 X X X X Little Sand Lake 78 14’ B X X Little Sissabagama 300 75’ A2 X X Long Lake 3,289 74’ X X X X Lost Land Lake 1,303 20’ A2 X X X Moose Lake 1,670 21’ A2 X X X Nelson Lake 2,502 33’ X X X X Round Lake 2,783 70’ A1 X X X X Sand Lake 928 46’ A1 X X X X Smith Lake 323 29’ X X X X Spider Lake 1,454 64’ A2 X X X Teal Lake 1,048 30’ A2 X X X Tigercat Flowage Chain 1,014 30’ B X X X Whitefish Lake 917 95’ A1 X X X X Windigo Lake 522 51’ X X X X Winter Lake 676 22’ A2 X X X Musky Water Classificaons: A1 - “Trophy waters" that consistently produce a num er of large muskellunge, ut overall a undance of muskellunge may e relavely low. -

The Chippewa Flowage Brochure

History of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band Chippewa Flowage Island Campsite Rules Wildlife Snowmobiles and ATVs The Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians The waters and surrounding lands of the Flowage provide abundant aquatic and There are a number of snowmobile trails on public and private lands near the Flowage, some trails of Wisconsin has been centered on several lakes in the area of the These simple rules are enforced to provide you with a clean, quiet, and safe experience on the terrestrial habitats. A diverse variety of northern forest and aquatic wildlife find food, nest cross the Flowage on the ice. Snowmobiles are allowed on public lands on designated trails only. headwaters of the Chippewa River since the mid-eighteenth century. Chippewa Flowage. Please enjoy your outing on the Flowage! sites and shelter along the many miles of undeveloped mainland and island shoreline. There are ATV trails on the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest property near the Flowage. Please The name comes from a large lake on the reservation’s western 1. Camping is allowed only at 5. Campsites are to be kept free 8. Please do not cut, carve or deface The state-owned lands on the Chippewa Flowage are open to hunting. Consult Wisconsin ride responsively and respect the property and rights of all landowners. boundary. Although the French name, Lac Courte Oreilles, literally designated, signed island of litter, rubbish and other trees, tables or benches, or drive hunting regulations for season dates, times and bag limits. Snowmobiles and ATVs are allowed on the ice of the Flowage, however, before venturing out onto translates to “Lake of the Short Ears,” the intention of the name is The Flowage provides exceptional nesting habitat for eagles and common loons. -

Land Management Plan For

Grindstone Lake Foundation Proposed Property Management Plan Grindstone Lake Cranberry Bog Property Grindstone Lake Cranberry Bog Applicant: Grindstone Lake Foundation Project: Acquisition of Grindstone Cranberry Bog Property Location: Bass Lake Township, Sawyer County PRIMARY GOALS OF THE PROJECT Upon permanent acquisition of approximately 57 acres of land formerly used as a commercial cranberry operation, the primary goals of the Grindstone Lake Foundation Property Management Plan will be to provide: (1) water quality protection through restoration and protection of wetland, shoreland, and upland portions of the property, specifically the use of native/natural landscape management, including no mow and no manicured landscaping and no additions of impervious surfaces or structures; (2) passive low-impact public recreational experiences; and, (3) educational experiences and demonstration sites that provide information about the importance of wetland, shoreline and nearshore habitats and land restoration. Success in achieving these goals will provide three significant benefits to the public. First, the 57-acre parcel and associated 1,537 linear feet of shoreline will be permanently protected from potential agricultural or residential development. This protection will prevent the introduction of nitrogen, phosphorus, and pesticides associated with potential agricultural and residential development from entering Grindstone Lake, classified as a Wisconsin Outstanding Water Resource. Second, visitors to the property will have recreational opportunities including hiking, biking, snowshoeing, cross-country skiing, and wildlife viewing along or near the shores of Grindstone Lake. Low impact trails will showcase and enhance the appreciation of the plant and animal life and support physical activity, an important public health goal. These recreational activities are currently not available on publicly accessible lands of this scale along a Wisconsin Outstanding Water Resource. -

The Anishinabe Nation's “Right to a Modest Living” from the Exercise Of

The Anishinabe Nation’s “Right to a Modest Living” From the Exercise of Off-Reservation Usufructuary Treaty Rights …. in All of Northern Minnesota Prof. Peter Erlinder Wm. Mitchell College of Law, St. Paul. MN [email protected]. INTRODUCTION……….…………………………………………………………………………1 I. The Treaties, Executive Orders, and Congressional Enactments Relevant to the Continuing Exercise of Usufructuary Rights in all of Northern Minnesota by the Anishinabe Nation:1825 to the Present. ……………………..…………………..…………7 II Modern Litigation Upholding Anishinabe Usufructuary Rights, under the Treaties of 1837, 1854 and 1855 ...…………………………………….……………...15 Lac Courte Oreilles v. Wisconsin (I-VIII): the Right to a “Modest Living” from Off -Reservation Usufructuary Rights in Wisconsin and Minnesota………………….......18 Minnesota v. Mille Lacs: The U.S. Supreme Court Confirms Continuing Validity of Off-reservation Anishinabe Usufructuary Rights……………………...............................….21 III. The Exercise of Traditional Usufructuary Rights in Modern Society………….............................24 IV. The Consequences of the State’s Failure to Apply the Lac Courte Oreilles and Mille Lacs Judgments to All Minnesota Anishinabe ................................………..…..……………………....27 The Fiscal Consequences of Minnesota’s Continuing Failure to Recognize Anishinabe Off-Reservation Usufructuary Rights………………..................……………..……………29 The Political-Economy of the Minnesota Anishinabe Nation’s “Right to a modest living” from Off-Reservation Usufructuary Rights………..…..………30 CONCLUSION…….……………………………………………………………………………...35 INTRODUCTION In 1837, the United States entered into a Treaty with several Bands of Chippewa Indians. Under terms of this Treaty, the Indians ceded land in present-day Wisconsin and Minnesota to the United States, and the United States guaranteed to the Indians certain hunting, fishing and gathering rights on the ceded land. We must decide whether the Chippewa Indians retain these usufructuary rights1 today. -

Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Memorandum of Understanding and Mutual Support By and Between Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa And Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction This Memorandum of Understanding and Mutual Support (hereinafter referred to as the “MOU”) is effective as of January 4, 2018, and is entered into by and between the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, 13394 West Trepania Road, Hayward, WI 54876 and the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 125 South Webster Street, Madison, WI 5370-7841 for the purpose of addressing issues of mutual interest to the parties regarding the education of school- age members of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. RECITALS: Whereas, the issues of mutual interest include promoting positive perceptions and improving the nature and scope of interactions between the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction; and, Whereas, the intention of this MOU is to provide a framework for respectful and cooperative communication that utilizes consensus building for improving programs and services; and, Whereas, the primary outcome intended by this MOU is to improve the planning, communication, and coordination between the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa regarding programs affecting the education of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa tribal members; and, Whereas, the parties intend to clarify their relationship to establish a common -

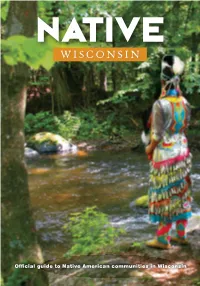

Official Guide to Native American Communities in Wisconsin C O N T E N T S

Official guide to Native American communities in Wisconsin C o n t e n t s 2 Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa 5 Forest County Potawatomi Tribe 8 Ho-Chunk Nation 11 Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Native Wisconsin serves as the official guide to Native American Lake Superior Chippewa Preserving our past. Sharing our future. Communities in Wisconsin. The publication has been produced and 14 Lac du Flambeau Band of printed with funding provided in part by the Wisconsin Department of Lake Superior Chippewa Tourism and Native American Tourism of Wisconsin (NATOW). The cooperative effort is spearheaded by the NATOW Advisory Board that 17 Tips for Visiting Indian consists of representatives from all the Wisconsin Tribes. Country/Annual Events Hello! NATOW was launched as a state wide initiative in 1994 by GLITC. 18 Annual Events The focus of this project is to promote tourism featuring Native American heritage and culture. NATOW holds an annual Tourism Conference, Welcome to Wisconsin’s Native American communities. Wisconsin is home to the largest 27 Menominee Nation look for details on the website. GLITC, founded in 1965 as a non-profit corporation, serves as a consortium of Wisconsin tribes. 30 Oneida Nation number of Native American tribes east of the Mississippi River. The reservations of NATOW has grown significantly over these last few years. All 33 Red Cliff Band of efforts are coordinated by their own Tourism Development Director, these eleven sovereign nations occupy more than one half million acres of Wisconsin’s Lake Superior Chippewa and the executive board members report directly to the GLITC Board of Directors. -

The Murder of Joe White: Ojibwe Leadership and Colonialism in Wisconsin

The Murder of Joe White: Ojibwe Leadership and Colonialism in Wisconsin A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Erik M. Redix IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Co-advisors: Brenda Child, American Studies Jean O’Brien, History November 2012 © Erik M. Redix, 2012 Acknowledgements This dissertation is the direct result of the generous support of many individuals who have shared their expertise with me over the years. This project has its roots from when I first picked up William Warren’s History of the Ojibwe People as a teenager. A love of Ojibwe history was a part of family: my great-aunt, Caroline Martin Benson, did exhaustive genealogical research for our family; my cousin, Larry Martin, former Chair of American Indian Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, showed me the possibilities of engaging in academia and has always been very warm and gracious in his support of my career. Entering college at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I was anxious to learn more about Native people in North America and Latin America. I would like to give thanks to Florencia Mallon for her generous support and mentorship of my Senior Thesis and throughout my time at Madison; she was always there to answer the many questions of a curious undergrad. I am also indebted to Ned Blackhawk, Patty Loew, and Rand Valentine for taking the time to support my intellectual growth and making a big university seem much smaller. After graduation, I returned home to work at Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Community College (LCOOCC), and eventually served as Chair of the Division of Native American Studies.