The Baker Trail - Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2006 Volume 6, Issue 2

Fall 2006 Volume 6, Issue 2 P.O. Box 35 Warrendale, PA 15086-0035 www.rachelcarsontrails.org [email protected] President’s Corner By Todd Chambers, President Inside This Issue Progress is being made on many fronts within our President’s Corner 1 organization. For years the Harmony Trails Council, the Trail Events Continue to Grow 1 predecessor of the Rachel Carson Trails Conservancy, laid the A Walk in the Woods 2 groundwork for the development of the Harmony Trail, from Volunteers Discuss Baker Trail Improvements 2 Wall Park in southern McCandless Township to Route 910 in Eagle Scout Projects Improve Trails 3 Pine Township. We acquired property and rights-of-way and established connections with local municipalities, the county, Volunteers Expand Community Trails 4 Event Calendar the state, a number of foundations, and other funding 4 sources. These past efforts have led to the tangible progress we now see. hike east across Route 19 to the McKinney Woods Trail, and over North Park trails to the beginning of the Rachel Carson Trail, With the incorporation of the Rachel Carson, Baker, and located on the east side of the park. Our past efforts with Pine Harmony trails to form the Rachel Carson Trails Conservancy, and McCandless Townships, Allegheny County, the Regional a broad network of trails across northern Allegheny County Asset District, the Allegheny Land Trust, the developers of Blue and through Westmoreland, Armstrong, Indiana, Jefferson, Heron Ridge and the Pittsburgh Foundation have all been Clarion and Forest Counties has come under our stewardship. instrumental in fostering this hike and the trail connection it This is a vast network of hiking opportunities accessing some celebrates. -

Events and Tourism Review

Events and Tourism Review December 2019 Volume 2 No. 2 Understanding Millennials’ Motivations to Visit State Parks: An Exploratory Study Nripendra Singh Clarion University Of Pennsylvania Kristen Kealey Clarion University Of Pennsylvania For Authors Interested in submitting to this journal? We recommend that you review the About the Journal page for the journal's section policies, as well as the Author Guidelines. Authors need to register with the journal prior to submitting or, if already registered, can simply log in and begin the five-step process. For Reviewers If you are interested in serving as a peer reviewer, please register with the journal. Make sure to select that you would like to be contacted to review submissions for this journal. Also, be sure to include your reviewing interests, separated by a comma. About Events and Tourism Review (ETR) ETR aims to advance the delivery of events, tourism and hospitality products and services by stimulating the submission of papers from both industry and academic practitioners and researchers. For more information about ETR visit the Events and Tourism Review. Recommended Citation Singh, N., & Kealey, K. (2019). Understanding Millennials’ Motivations to Visit State Parks: An Exploratory Study. Events and Tourism Review, 2(2), 68-75. Events and Tourism Review Vol. 2 No. 2 (Fall 2019), 68-75, DOI: 10.18060/23259 Copyright © 2019 Nripendra Singh and Kristen Kealey. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribuion 4.0 International License. Singh, N., & Kealey, K. (2019) / Events and Tourism Review, 2(2), 68-75. 69 Abstract State Park’s scenic stretches of flowing rivers and large lakes are popular for canoeing, kayaking, and tubing, but how much of these interests’ millennials are not much explored. -

Pennsylvania Wilds

PENNSYLVANIA WILDS OUTDOOR DISCOVERY ATLAS Ramm Road Vista, Lycoming County Lycoming Vista, Ramm Road I-80 Frontier Landscape I-80 Frontier Landscape Groundhog Day Celebration, Punxsutawney Celebration, Day Groundhog PA WILDS’ WELCOME MAT, FAST TRACK TO THE WILDS Whether you’re coming from the east, south or west, the I-80 Frontier is the quintessential welcome mat to the PA Wilds. With its proximity to Pennsylvania’s southern population centers of Philadelphia, Harrisburg and Pittsburgh, not to mention close by New York City and Cleveland on the western side, it’s easy to plan a trip for each season. Home to forested state parks and storied towns and places, any given exit off the interstate is a surefire way to find and explore the natural and hidden wonders of the region. Going from east to west, three I-80 Frontier towns – Williamsport, Lock Haven “The fastest way into The and Clearfield – all feature beautiful riverfront parks and walking paths on the Wilds is via Interstate 80, West Branch of the Susquehanna River. Roughly central to the 1-80 frontier is which parallels its Clearfield, where you can grab a bite to eat before heading south to Bilger’s rocks in the tiny borough of Grampian, where you’ll find towering boulders Millionaires’ Row, Williamsport Row, Millionaires’ southern reaches.” and rock formations set throughout the forest. Or stop off in Punxsutawney - Newsday and visit the world’s most famous weather-predicting groundhog, Phil! If you’re a New Yorker, Clevelander, Philadelphian, or Pittsburgher, a visit (or two) to the PA Wilds I-80 Frontier will undoubtedly change your perception on that long and winding interstate that welcomes you to your PA Wilds adventure. -

HISTORY of PENNSYLVANIA's STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015

i HISTORY OF PENNSYLVANIA'S STATE PARKS 1984 to 2015 By William C. Forrey Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Office of Parks and Forestry Bureau of State Parks Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Copyright © 2017 – 1st edition ii iii Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. vii CHAPTER I: The History of Pennsylvania Bureau of State Parks… 1980s ............................................................ 1 CHAPTER II: 1990s - State Parks 2000, 100th Anniversary, and Key 93 ............................................................. 13 CHAPTER III: 21st CENTURY - Growing Greener and State Park Improvements ............................................... 27 About the Author .............................................................................................................................................. 58 APPENDIX .......................................................................................................................................................... 60 TABLE 1: Pennsylvania State Parks Directors ................................................................................................ 61 TABLE 2: Department Leadership ................................................................................................................. -

Armstrong County.Indd

COMPREHENSIVE RECREATION, PARK, OPEN SPACE & GREENWAY PLAN Conservation andNatural Resources,Bureau ofRecreation andConservation. Keystone Recreation, ParkandConservationFund underadministrationofthe PennsylvaniaDepartmentof This projectwas June 2009 BRC-TAG-12-222 fi nanced inpartbyagrantfrom theCommunityConservation PartnershipsProgram, The contributions of the following agencies, groups, and individuals were vital to the successful development of this Comprehensive Recreation, Parks, Open Space, and Greenway Plan. They are commended for their interest in the project and for the input they provided throughout the planning process. Armstrong County Commissioners Patricia L. Kirkpatrick, Chairman Richard L. Fink, Vice-Chairman James V. Scahill, Secretary Armstrong County Department of Planning and Development Richard L. Palilla, Executive Director Michael P. Coonley, AICP - Assistant Director Sally L. Conklin, Planning Coordinator Project Study Committee David Rupert, Armstrong County Conservation District Brian Sterner, Armstrong County Planning Commission/Kiski Area Soccer League Larry Lizik, Apollo Ridge School District Athletic Department Robert Conklin, Kittanning Township/Kittanning Township Recreation Authority James Seagriff, Freeport Borough Jessica Coil, Tourist Bureau Ron Steffey, Allegheny Valley Land Trust Gary Montebell, Belmont Complex Rocco Aly, PA Federation of Sportsman’s Association County Representative David Brestensky, South Buffalo Township/Little League Rex Barnhart, ATV Trails Pamela Meade, Crooked Creek Watershed -

Historic Resource File

John Mi 1 ner PENNSYLVANIA HISTORIC RESOURCE SURVEY FORM 1. Local ,urvy organization Associates BUREAU FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION 1133 Arch Street, P deiphia, PA 19107 PA HISTORICAL MUSEUM COMMISSIONS I. rLPA.17120 (215) 56I7637 ' nurnber/other number S. ropsny owns rismi and address taxP"°1 I I U.T.M. PA Department, of Environmental Resources Bureau of State Parks 1. status (Thirsurveyl. I Box 1467 . ______jlg t i PA State Parks u5 northing Harrisburg, PA 17120 Survey: 1983 ~I Black Moshannon I.- 12. classification 13.f(*J(d,t.rmIn.d) 15. style. design or folk type 19. original use Family Cabins ft. ( ) structure building ( ) district IT 14. 2O prese period 1925-1949 Rustic nt use Family Cabins 21. 16. architect or sngin..r 17. contractor or builds, IS. primary building matjconstruc. condition Good 22. Integrity CCC Camp S-71 Stone/Wood Excellent site plan with north arrow - - a'i e. BLACK AND WHITE PRINT(S) 31/2" x B" .rllargamsnt or m.dium format contact not, location of negative in block 24. I là photo notation See accompanying photos. Ills/location 26. brief d..triptlon (note unusual features, Integrity. .nvironmsnt, threats and associated buildings) Black Moshannon State Park encompasses 3,481 acres surrounded by Moshannon State Forest in Centre County. The centerpiece of the park is Black Moshannon Lake. Most of the park's recreational facilities are grouped around the lake. Three separate historic districts are proposed for nomination to the National (continue on back lffl.cSSWy) 21. history. significance and/or b.ckground CCC Camp S-71 began work at Black Moshannon State Park in May 1933. -

Pennsylvania State Parks

Pennsylvania State Parks Main web site for Dept. of Conservation of Natural Resources: http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/index.aspx Main web site for US Army Corps of Engineers, Pittsburgh District: http://www.lrp.usace.army.mil/rec/rec.htm#links Allegheny Islands State Park Icon#4 c/o Region 2 Office Prospect, PA 16052 724-865-2131 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/alleghenyislands.aspx Recreational activities Boating The three islands have a total area of 43 acres (0.17 km²), with one island upstream of Lock and Dam No. 3, and the other two downstream. The park is undeveloped so there are no facilities available for the public. At this time there are no plans for future development. Allegheny Islands is accessable by boat only. Group camping (such as with Scout Groups or church groups) is permitted on the islands with written permission from the Department. Allegheny Islands State Park is administered from the Park Region 2 Office in Prospect, Pennsylvania. Bendigo State Park Icon#26 533 State Park Road Johnsonburg, PA 15845-0016 814-965-2646 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/bendigo.aspx Recreational activities Fishing, Swimming, Picnicking The 100-acre Bendigo State Park is in a small valley surrounded with many picturesque hills. About 20 acres of the park is developed, half of which is a large shaded picnic area. The forest is predominantly northern hardwoods and includes beech, birch, cherry and maple. The East Branch of the Clarion River flows through the park. -

Alternative Trails.Xlsx

Wandering off the Beaten Path: Less Traveled Long Distance Trails in the Appalachian Mountains “Are you looking for a new adventure? . Been itching to return to long-distance hiking... anxious for something a bit more challenging” (Jenkins). Try wandering off the beaten path in the Appalachian Mountains. The Appalachian Mountains in North America, range from the southern foothills in Alabama north into Labrador and Newfoundland. They are identifiable through 18 states and 5 Canadian provinces. All this territory and yet it may come as a surprise to many that the Appalachian National Scenic Trail (AT) is not the only long-distance trail available to hike in the system. As long-distance hiking becomes more and more popular trails like the AT see more hikers, to the point of overuse. People wishing to get away from it all may want to consider a less traveled path. Some of these less traveled trails interlink more than once with the AT and so can provide the bonus of a loop hike. Other trails connecting to the AT can offer an AT thru hiker the opportunity to continue hiking well beyond Katahdin. Shorter trails present the prospect of thru-hiking a trail without needing to quit one's job for 6 months. Hiking one of the shorter trails can also serve as a shakedown in preparation for a potential longer distance hike. This critical preparation not only helps hikers make great gear decisions but will help them to discover if they even would enjoy a 6 month hike. Most of the trails are more remote than the AT and offer less in the way of hiker amenities or hostels. -

Ways to Celebrate the Quasiquicentennial

HAPPY 125TH ANNIVERSARY PENNSYLVANIA STATE PARKS AND FORESTS! HERE’SHERE’S HOWHOW YOUYOU CANCAN CELEBRATECELEBRATE This booklet provides ideas for activities you can take within Pennsylvania state parks and forests to celebrate the 125-year anniversary. Select one or more actions, check the box, journal your thoughts, take photos, and have some fun in the process! A special gift is available to anyone who completes three or more of the activities listed in this booklet. Just take a photo of your activities and send it to [email protected].. SPEND 125 HOURS IN 2018 EXPLORING STATE PARKS AND FORESTS With 121 state parks covering nearly 300,000 acres and 20 forest districts spanning 2.2 million acres across Pennsylvania, there are endless opportunities to get outdoors and explore! What you do there is not as important as simply being there, as time spent outdoors has many health benefits. Currently, Pennsylvania ranks as the 17th most obese state in the country. According to the Penn State University study, “Obesity Threatens America’s Future,” by 2020 57 percent of Pennsylvanians will be obese and related health care costs will surpass $13.5 billion. The study goes on to show that reducing the average body mass index in Pennsylvania by only five percent could mean an $8 billion-dollar savings in health care costs in the next 10 years and $24 billion in the next 20 years. There is strong evidence that when people have access to parks and forests they exercise more, leading to a reduction in obesity. The National Institutes of Health have shown that being more fit leads to a reduction in time spent being sick, which has benefits to productivity and quality of life. -

Discover More About the Clarion River Project and Greenway

Clarion River Greenway Connecting Our Past with a Vision for Our Future Clarion River Greenway Plan Table of Contents Title Page Table of Contents…………...………………………………………… ……………….….i List of Table and Figures...……………………………………………… …………….....ii Acknowledgments…………………………………………………….………………….iii Executive Summary…………………………………………………….…….…………...v The Past…………………………………………………………………..………………..1 The Present………………………………………………………………..……………….4 The Potential………………………………………………………………..……………..9 Development of the Clarion River Greenway Plan…………………………..………….14 Clarion River Greenway Economic Overview………………………………..…………19 Reach #1: Ridgway to the Clarion River Ghost Towns (Little Toby Creek)…………………………………….………...23 Reach #2: Clarion River Ghost Towns to Allegheny National Forest (Irwintown)…………………………………….…….....31 Reach #3: Allegheny National Forest to Clear Creek State Forest……………………………………………….……….39 Reach #4: Clear Creek State Park to Cook Forest State Park……………………………………………………….…..…....48 Reach #5: Cook Forest State Park to the Piney Dam Backwaters……………………………………………….…..…….54 Issues, Opportunities, and Challenges: An Overview of the Clarion River Greenway Public Meetings………………...…………61 Implementation of the Clarion River Greenway……………………………….…..…….70 References……………………………………………………………………….……….78 Appendix A: Hubs of the Clarion River Greenway……………………………….……A-1 Appendix B: Clarion River Greenway Public Meeting Transcripts …….………..........B-1 Appendix C: Camping Regulations within the Clarion River Greenway………............C-1 Appendix D: Clarion River Greenway Business -

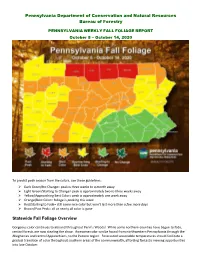

FALL FOLIAGE REPORT October 8 – October 14, 2020

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Bureau of Forestry PENNSYLVANIA WEEKLY FALL FOLIAGE REPORT October 8 – October 14, 2020 TIOGA CAMERON BRADFORD To predict peak season from the colors, use these guidelines: ➢ Dark Green/No Change= peak is three weeks to a month away ➢ Light Green/Starting to Change= peak is approximately two to three weeks away ➢ Yellow/Approaching Best Color= peak is approximately one week away ➢ Orange/Best Color= foliage is peaking this week ➢ Red/Starting to Fade= still some nice color but won’t last more than a few more days ➢ Brown/Past Peak= all or nearly all color is gone Statewide Fall Foliage Overview Gorgeous color continues to abound throughout Penn’s Woods! While some northern counties have begun to fade, central forests are now stealing the show. Awesome color can be found from northwestern Pennsylvania through the Alleghenies and central Appalachians, to the Pocono region. Forecasted seasonable temperatures should facilitate a gradual transition of color throughout southern areas of the commonwealth, affording fantastic viewing opportunities into late October. Northwestern Region The district manager in Cornplanter State Forest District (Warren, Erie counties) stated that cool nights have brought on a splendid array of colors on the hillsides of northwestern Pennsylvania. Although peak is still more than a week away, every shade of yellow, red, orange, and brown is represented in the forested landscape. It’s a great time to get outdoors and take advantage of the autumn experience and the many opportunities to walk forested trails carpeted in newly fallen leaves! To view and enjoy the fall foliage by vehicle, consider taking routes 666, 62, 59, or 321. -

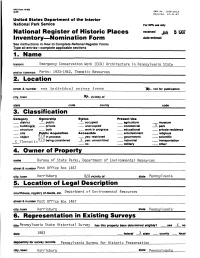

3. Classification 4. Owner of Property

NFS Form 10-900 0.82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Architecture in Pennsylvania State and or common Parks: 1933-1942, Thematic Resources 2. Location street & number see individual survey fo^ms not for publication city, town vicinity of state code county code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district A public occupied agriculture museum .. building(s) private unoccupied commercial X park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible __ entertainment __ religious object N ' A in process yes: restricted __ government __ scientific X Thematic^ beln9 considered X.. "noyes: unrestricted __ industrial __ transportation __ military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name Bureau of State Parks, Department of Environmental Resources street & number Post Office Box 1467 city, town Harrisburg N/A vicinity of state Pennsylvania 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Department of Environmental Resources street & number Post Office Box 1467 city, town Harrisburg state Pennsylvania 6. Representation in Existing Surveys_________ title Pennsylvania State Historical Survey has this property been determined eligible? __