How Prophecy Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Time to Gather Stones

A Time to Gather Stones A look at the archaeological evidences of peoples and places in the scriptures This book was put together using a number of sources, none of which I own or lay claim to. All references are available as a bibliography in the back of the book. Anything written by the author will be in Italics and used mainly to provide information not stated in the sources used. This book is not to be sold Introduction Eccl 3:1-5 ; To all there is an appointed time, even time for every purpose under the heavens, a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pull up what is planted; a time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to tear down, and a time to build up; a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; a time to throw away stones, and a time to gather stones… Throughout the centuries since the final pages of the bible were written, civilizations have gone to ruin, libraries have been buried by sand and the foot- steps of the greatest figures of the bible seem to have been erased. Although there has always been a historical trace of biblical events left to us from early historians, it’s only been in the past 150 years with the modern science of archaeology, where a renewed interest has fueled a search and cata- log of biblical remains. Because of this, hundreds of archaeological sites and artifacts have been uncovered and although the science is new, many finds have already faded into obscurity, not known to be still existent even to the average believer. -

The Philadelphia

SPECIAL ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE King David’s palace | A secret water tunnel | Solomon’s wall | An ancient inscription | Seals of Jeremiah’s captors | Nehemiah’s wall | A Jewish refuge THE PHILADELPHIA TRUMPEToctober/november 2013 | thetrumpet.com Rich History EILAT MAZAR finds an ancient Jewish treasure near Jerusalem’s Temple Mount T OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2013 VOL. 24, NO. 9 CIRC. 331,830 “This happens only once in a lifetime.” DR. EILAT MAZAR STRIKING GOLD Archaeolo- gists scoop up a 1,400-year-old gold hoard on the Ophel in Jerusalem. SPECIAL ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE 15 NEHEMIAH The Wall Built in WORLD 1 FROM THE EDITOR The World’s 52 Days 30 WORLDWATCH Pay attention Most Important to Cairo unrest • Crossing the 16 THE JEWS A Desperate Struggle red line • Arab Spring 2.0 Archaeological Dig for Safety DEPARTMENTS 2 Wealth of History 18 INFOGRAPHIC The Strata of Jerusalem’s History 4 One Sweet Summer Internship 34 Discussion Board 5 Israel’s Enduring Symbol 20 EDMOND, OKLAHOMA Welcome to 36 Television Log Our Exhibit! 3 Q&A With Eilat Mazar 22 Why the Exhibit? COVER : 6 EILAT MAZAR Like a Rock 23 Rewarding Partnership PHOTO : OURIA 8 KING DAVID A Palace Fit for a King 26 The Tombs of the Kings 29 ‘The House of My Fathers’ Sepulchres’ TADMOR 10 KING SOLOMON The Royal Quarter / COPYRIGHT 12 JOAB A Secret Tunnel 33 PRINCIPLES OF LIVING The Lesson of Hezekiah’s Tunnel : 13 The City’s Earliest Inscriptions 35 COMMENTARY The Armstrong-Mazar Family EILAT MAZAR 14 JEREMIAH Enemies of a Prophet The World’s Most Important Archaeological Dig o celebrate the announcement of the menorah woman next to me said hello. -

5. the Fall of Jerusalem & Its Aftermath Jeremiah 36-45

5. THE FALL OF JERUSALEM & ITS AFTERMATH JEREMIAH 36-45 251 Do not resist Babylon Introduction to 36-45 It is clear from Jeremiah’s oracles that he was critical of the political and religious lead- ership in Jerusalem under King Jehoiakim in the years that preceded the capture of the city by the Babylonian army in 597, and under his brother Zedekiah, the puppet ruler in the years between 597 and 587, when Jerusalem was sacked. Jeremiah’s focus was not political, though he saw the collapse of Jerusalem as divine punishment for the failure of the leaders and the people to obey the Torah. They gave mouth service to Yahwism, but neglected to obey the Torah, and so showed their failure to grasp the essence of what it means to be in a covenant relationship with YHWH. Clearly there were those in Jerusalem at this time who favoured resistance to Babylon and who favoured throwing in their lot with Egypt. There was also a minority group who favoured submitting to what they saw as inevitable. They were in favour of avoid- ing resistance to Babylon. They failed to win the day, but the calamitous events of 597 and 587 demonstrated the abysmal failure of the official ideology. Judah was ravaged, Jerusalem and its temple destroyed, and the Promised Land lost. It was this group that favoured submitting to Babylon that came into its own in exile. The prophet Jeremiah was largely ignored and persecuted during the reigns of Jehoiakim and Zedekiah, but the pro-Babylonian (or perhaps better, the not-contra Babylonian) party was happy to claim him as one of them, once his oracles were proved true by events. -

The Context Bible Life Group Lesson 8

The Context Bible Life Group Lesson 8 John 4:27 - 4:45 Introduction to the Context Bible Have you ever wished the Bible was easier to read through like an ordinary book – cover to cover? Because the Bible is a collection of 66 books, it makes reading like an ordinary book quite difficult. Compounding this difficulty is the fact that the later writers of the New Testament, were often quoting or referencing passages in the Old Testament. In fact, much of the New Testament makes better sense only if one also considers the Old Testament passages that place the text into its scriptural context. You are reading a running commentary to The Context Bible. This arrangement of Scripture seeks to overcome some of these difficulties. Using a core reading of John’s gospel, the book of Acts, and the Revelation of John, the Context Bible arranges all the rest of Scripture into a contextual framework that supports the core reading. It is broken out into daily readings so that this program allows one to read the entire Bible in a year, but in a contextual format. Here is the running commentary for week eight, along with the readings for week nine appended. Join in. It’s never to late to read the Bible in context! Week Eight Readings www.Biblical-Literacy.com © Copyright 2014 by W. Mark Lanier. Permission hereby granted to reprint this document in its entirety without change, with reference given, and not for financial profit. JESUS’ FOOD (John 4:27-38) At the end of Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman, his disciples caught up with him and were stunned to find that Jesus had been talking with a woman. -

Discipleship University Bible Reading Guide Hebrew Prophets II: Jer

Discipleship University Bible Reading Guide Hebrew Prophets II: Jer. 32-33, 37-43, Ezekiel 25-31, Lamentations (For class to be held on December 2, 2017) Read Jeremiah 37, Ezekiel 29:1-16 & 30:1-19 – Siege Lifted, Jeremiah Imprisoned, Prophecy for Egypt 1. What turn of events led Zedekiah to send Jehucal and Zephaniah to inquire of the LORD through Jeremiah? ________________________________________________________. What did Jeremiah say would happen? ___________________________________________________. When Jeremiah tried to leave Jerusalem why was he put in prison? ________________________________ 2. Who is symbolized by the great dragon in the river in Ez. 29:3? ___________. What would the fish sticking to his scales possibly represent? _____________. In 29:8-10, 14-16, we learn that after the destructive invasion of Egypt, it would be revived as a nation. What was prophesied about Egypt’s future greatness? ____________________________________________________. What nation’s destruction is described in Ez. 30:1-19? ________ Jeremiah 32-33 – A Curious Land Purchase & The Future Glorious Restoration of Judah and Jerusalem 1. What was ironic about Jeremiah buying land? _________________________________. What message was given through Jeremiah’s purchase of land? ____________________________________________ ________________________________________________ 2. When God would cure and return the captivity of Israel, what specific promise given in Jer. 33 could only be fulfilled by the Messiah’s sacrifice? ______________________________________. What name is given to the coming Messiah? _________________________________________. Why is the promise that “David shall never want a man to sit upon the throne” so strange in this chapter? ______________ ____________________________________________________. What did God say was the only way His covenant with David and the Levites and priests could be broken? ___________________________ 3. -

Jeremiah 38:1-13 Sinking Down and Being Lifted up September 20, 2015

Jeremiah 38:1-13 Sinking Down and Being Lifted Up September 20, 2015 Shephatiah son of Mattan, Gedaliah son of Pashhur, Jehucal son of Shelemiah, and Pashhur son of Malkijah heard what Jeremiah was telling all the people when he said, “This is what the LORD says: ‘Whoever stays in this city will die by the sword, famine or plague, but whoever goes over to the Babylonians will live. He will escape with his life; he will live.’ And so this is what the LORD says: ‘This city will certainly be handed over to the army of the king of Babylon, who will capture it.’” Then the officials said to the king, “This man should be put to death. He is discouraging the soldiers who are left in this city, as well as all the people, by the things he is saying to them. This man is not seeking the good of these people but their ruin.” “He is in your hands,” King Zedekiah answered. “The king can do nothing to oppose you.” So they took Jeremiah and put him into the cistern of Malkijah, the king’s son, which was in the courtyard of the guard. They lowered Jeremiah by ropes into the cistern; it had no water in it, only mud, and Jeremiah sank down into the mud. Jeremiah should have known this would happen. Common sense and experience will tell you that when you tell people things they don’t want to hear—and especially when you tell them things they don’t want to hear and admit about themselves—it rarely goes well. -

The Books of Jeremiah & Lamentations

Supplemental Notes: The Books of Jeremiah & Lamentations Compiled by Chuck Missler © 2007 Koinonia House Inc. Audio Listing Jeremiah Chapter 1 Introduction. Historical Overview. The Call. Jeremiah Chapters 2 - 5 Remarriage. The Ark. Return to Me. Babylon. Jeremiah Chapters 6 - 8 Temple Discourses. Idolatry and the Temple. Shiloh. Acknowledgments Jeremiah Chapters 9 - 10 These notes have been assembled from speaking notes and related Diaspora. Professional Mourners. Poem of the Dead Reaper. materials which had been compiled from a number of classic and con- temporary commentaries and other sources detailed in the bibliography, Jeremiah Chapters 11 - 14 as well as other articles and publications of Koinonia House. While we have attempted to include relevant endnotes and other references, Plot to Assassinate. The Prosperity of the Wicked. Linen Belt. we apologize for any errors or oversights. Jeremiah Chapters 15 - 16 The complete recordings of the sessions, as well as supporting diagrams, maps, etc., are also available in various audiovisual formats from the Widows. Withdrawal from Daily Life. publisher. Jeremiah Chapters 17 - 18 The Heart is Wicked. Potter’s House. Jeremiah Chapters 19 - 21 Foreign gods. Pashur. Zedekiah’s Oracle. Page 2 Page 3 Audio Listing Audio Listing Jeremiah Chapter 22 Jeremiah Chapters 33 -36 Throne of David. Shallum. Blood Curse. Concludes Book of Consolation. Laws of Slave Trade. City to be Burned. Rechabites. Jeremiah Chapter 23 Jeremiah Chapters 37 - 38 A Righteous Branch. Against False Prophets. Jeremiah’s experiences during siege of Jerusalem. Jeremiah Chapters 24 - 25 Jeremiah Chapter 39 Two Baskets of Figs. Ezekiel’s 430 Years. 70 Years. Fall of Jerusalem. -

Thematic Correspondences Between the Zedekiah Texts of Jeremiah (Jer 21–24; 37–38) 1

Widder, “Thematic Correspondences,” OTE 26/2 (2013): 491-503 491 Thematic Correspondences between the Zedekiah Texts of Jeremiah (Jer 21–24; 37–38) 1 WENDY L. WIDDER (LOGOS BIBLE SOFTWARE ) ABSTRACT This article argues that the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of Jer 37–38 correspond thematically to the Zedekiah Cycle of chs. 21–24 in at least two important ways. First, the later chapters provide a narrative enactment of the judgment on Judah’s institutions that the Zedekiah Cycle foretold, namely, judgment on Zedekiah himself and the entire Judahite kingship. Secondly, in the character of Ebed- Melech, the chapters include a narrative prefiguring of the “right- eous branch” foretold in 23:5–6. To demonstrate these correspon- dences, the article first examines the narrative structure of the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of chs. 37–38 and determines that the focus of the narrative is the unjust imprisonment and suffering of Jeremiah. The article then explores how this narrative structure provides a backdrop for understanding both Zedekiah and Ebed- Melech, especially in light of the earlier prophecies of the Zedekiah Cycle. A INTRODUCTION The book of Jeremiah includes two blocks of text that feature Zedekiah: the Zedekiah Cycle of chapters 21–24 and the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of chapters 37–38. While others have analyzed these respective blocks of Zede- kiah texts 2 and probed the redactional development of Zedekiah as a character, 3 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Milwaukee, on Nov 16, 2012. 2 E.g., Mary C. -

Remembering the World's Most Important Archaeologist

AUGUST 2021 VOL. 32, NO. 7 CIRC. 239,545 FROM THE EDITOR 1 Remembering the FROM THE EDITOR GERALD FLURRY World’s Most Important Archaeologist Remembering Dr. Eilat Mazar 1956–2021 3 Is the Fall of East Jerusalem the World’s Imminent? 4 It’s a Woman’s World 9 Most Important Russia, China and a World of Nuclear Weapons 14 Archaeologist Cyberattacks Expose Our Fragile World 17 Our friend Dr. Eilat Mazar left a dazzling legacy. When the Harvest Fails 20 • No One Fears Germany 25 erusalem archaeologist Eilat Mazar died on May 25 at age 64. She was a courageous woman of indomitable Joe Biden’s Border J strength and fierce determination, an inspiration to many Catastrophe 26 thousands of people around the world, and to me personally. • Drug Cartels Are in Although she did not regard herself as personally religious, Control 30 her sense of intellectual and scientific honesty and inquiry led Dr. Mazar to use the Bible as a crucial, historically accurate Are ‘Anglo-Saxon’ Values document. This led her to some of the most powerful and Really Racist? 32 sensational archaeological discoveries ever! Dr. Mazar’s love of archaeology—and our organization’s WORLDWATCH 35 connection with her—began when she was a child. I enrolled in Ambassador College in 1967, the same year the Six-Day War SOCIETYWATCH 39 broke out in Israel. God intervened and gave Israel a miraculous victory that awarded the Jews control of East Jerusalem. The PRINCIPLES OF LIVING 40 following year, Israelis began what they called the “Big Dig,” a The Right Way to Obey God massive archaeological excavation at the southern part of the Temple Mount. -

Discovered Discovered

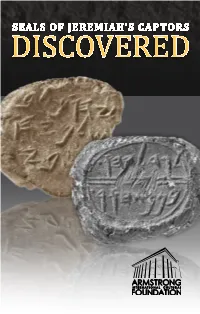

SEALS OF JEREMIAH’S CAPTORS DISCOVERED Dear visitor, Welcome! We are thrilled to be able to share these precious artifacts, and the remarkable history of ancient Israel. Biblical history is a fascinating and important subject. These relics bring to King Solomon, the heartache of Judah’s life the magnificence of ancient Israel under captivity and Jerusalem’s destruction, and the impressive faith and courage of the Prophet Jeremiah. We encourage you to take as much time as you need to let this history—and the lessons it imparts—sink in. We would also like to express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Eilat Mazar for her vital contributions to this exhibit. Were it not for the tireless efforts of Dr. Mazar and her late grandfather, Professor Benjamin Mazar, many of these artifacts, including the bullae, would lay undiscovered in the soils of Jerusalem. We treasure our long history with the Mazar family and consider it a tremendous blessing to have been by her and her grandfather’s side these past 44 years. We stand ready, spade in hand, to support Dr. Mazar as she continues to uncover the secrets of ancient Jerusalem. GERALD FLURRY FOUNDER AND CHAIRMAN ARmstRONG INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 2012 EXHIBITION 1 c. 1447 b.c. Israelite exodus 1407 b.c. Israelites enter from Egypt. Promised Land. United Kingdom King David ruled Israel from the city of Hebron for 7½ years (circa 1007 ). Although the Israelites had entered Canaan more than 400 years prior, one city remained unconquered: Jerusalem. Situated right in the b.c. lived there boasted that “the blind and the lame” could defend it. -

A Commentary on the Book of Jeremiah by Pastor Galen L

A Commentary on the Book of Jeremiah By Pastor Galen L. Doughty Southside Christian Church June 2014 INTRODUCTION: This commentary is based upon my personal devotional notes and reflections on the Book of Jeremiah. It is intended to help you better understand some of the background and issues in Jeremiah’s prophecy. It is not a technical commentary designed for academic projects. This material is intended for use by members and friends of Southside Christian Church, especially our Life Group leaders to help you lead your group in a verse by verse study of Jeremiah. However, I do not include discussion questions in the commentary. That I leave up to you as a group leader. In the commentary there are occasional references to the original Hebrew words Jeremiah used in a particular passage. Those Hebrew words are always quoted in italics and are transliterated into English from the Hebrew. I go chapter by chapter in the commentary and sometimes individual verses are commented upon, sometimes it is several sentences and sometimes a whole paragraph. This commentary is based on the New International Version and all Scripture quotations are taken from that version of the Bible. Books of the Bible, Scripture references and quotes are also italicized. KEY HISTORICAL DATES IN THE TIMELINE OF JEREMIAH: Assyria is weakened. Amon son of Manasseh, King of Judah is assassinated, 640. Eight year old Josiah son of Amon becomes King of Judah, 640. Jeremiah called to be a prophet, 627 (the 13th year of Josiah). Josiah begins his reforms, 622. The Book of the Law is found in the temple, 621; 2 Kings 23:1-25. -

Through the Bible – Jeremiah 70 Years of Exile

RESOURCES Preaching the Word Commentary Series - R. Kent Hughes (ed.) Calvary Chapel Lynchburg presents BiblicalArchaeology.org | GotQuestions.org Through the Jeremiah (NICOT) - John A. Thompson New American Commentary, vol. 16 - F. B. Huey Bible cclburg.com/ThroughTheBible with Pastor Troy Warner My Notes Jeremiah The book of Jeremiah is a long story of one man’s faithfulness in the face of failure. It is a bleak picture of Israel’s determined self-destruction amidst countless impassioned warnings from the Weeping Prophet. In it we get a decades-long look at the ministry of Jeremiah building up to the destruction of Jerusalem and the beginning of the Exile at the hands of Babylon. While tragic, the book gives us a full picture of the character of God, both His unshakeable justice and boundless mercy. Even after what seems like the end of the people of God, Jeremiah gives hope for the end of the Exile and the restoration of his city. August 9, 2017 About Jeremiah Author: Jeremiah (with Baruch) Date: ca. 580 BC Genre: Prophecy Purpose: To record the long prophetic ministry of Jeremiah leading up to the fall of Jerusalem and the beginning of the Exile. Characteristics: Long prophetic passages interspersed with short narratives of Jeremiah’s life; the tone is heartbreaking and tragic. Outline These clay bullae (seal impressions), discovered in the City of David, Jerusalem, bear the I. Judgment on Judah and Jerusalem (1-25) names of two royal ministers mentioned in the book of Jeremiah. The first bears the name “Jehucal ben Shelemiah” (left), the second “Gedaliah ben Pashur” (right).