Arxiv:1705.03481V3 [Math.GT] 8 Feb 2018 H Eflnignme Nta Ftesl-Ikn Matrix Self-Linking the of Instead Number with Self-Linking Consticency the for However, Matrix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutant Knots and Intersection Graphs 1 Introduction

Mutant knots and intersection graphs S. V. CHMUTOV S. K. LANDO We prove that if a finite order knot invariant does not distinguish mutant knots, then the corresponding weight system depends on the intersection graph of a chord diagram rather than on the diagram itself. Conversely, if we have a weight system depending only on the intersection graphs of chord diagrams, then the composition of such a weight system with the Kontsevich invariant determines a knot invariant that does not distinguish mutant knots. Thus, an equivalence between finite order invariants not distinguishing mutants and weight systems depending on intersections graphs only is established. We discuss relationship between our results and certain Lie algebra weight systems. 57M15; 57M25 1 Introduction Below, we use standard notions of the theory of finite order, or Vassiliev, invariants of knots in 3-space; their definitions can be found, for example, in [6] or [14], and we recall them briefly in Section 2. All knots are assumed to be oriented. Two knots are said to be mutant if they differ by a rotation of a tangle with four endpoints about either a vertical axis, or a horizontal axis, or an axis perpendicular to the paper. If necessary, the orientation inside the tangle may be replaced by the opposite one. Here is a famous example of mutant knots, the Conway (11n34) knot C of genus 3, and Kinoshita–Terasaka (11n42) knot KT of genus 2 (see [1]). C = KT = Note that the change of the orientation of a knot can be achieved by a mutation in the complement to a trivial tangle. -

![Deep Learning the Hyperbolic Volume of a Knot Arxiv:1902.05547V3 [Hep-Th] 16 Sep 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8117/deep-learning-the-hyperbolic-volume-of-a-knot-arxiv-1902-05547v3-hep-th-16-sep-2019-158117.webp)

Deep Learning the Hyperbolic Volume of a Knot Arxiv:1902.05547V3 [Hep-Th] 16 Sep 2019

Deep Learning the Hyperbolic Volume of a Knot Vishnu Jejjalaa;b , Arjun Karb , Onkar Parrikarb aMandelstam Institute for Theoretical Physics, School of Physics, NITheP, and CoE-MaSS, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, WITS 2050, South Africa bDavid Rittenhouse Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania, 209 S 33rd Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: An important conjecture in knot theory relates the large-N, double scaling limit of the colored Jones polynomial JK;N (q) of a knot K to the hyperbolic volume of the knot complement, Vol(K). A less studied question is whether Vol(K) can be recovered directly from the original Jones polynomial (N = 2). In this report we use a deep neural network to approximate Vol(K) from the Jones polynomial. Our network is robust and correctly predicts the volume with 97:6% accuracy when training on 10% of the data. This points to the existence of a more direct connection between the hyperbolic volume and the Jones polynomial. arXiv:1902.05547v3 [hep-th] 16 Sep 2019 Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Setup and Result3 3 Discussion7 A Overview of knot invariants9 B Neural networks 10 B.1 Details of the network 12 C Other experiments 14 1 Introduction Identifying patterns in data enables us to formulate questions that can lead to exact results. Since many of these patterns are subtle, machine learning has emerged as a useful tool in discovering these relationships. In this work, we apply this idea to invariants in knot theory. -

A Remarkable 20-Crossing Tangle Shalom Eliahou, Jean Fromentin

A remarkable 20-crossing tangle Shalom Eliahou, Jean Fromentin To cite this version: Shalom Eliahou, Jean Fromentin. A remarkable 20-crossing tangle. 2016. hal-01382778v2 HAL Id: hal-01382778 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01382778v2 Preprint submitted on 16 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A REMARKABLE 20-CROSSING TANGLE SHALOM ELIAHOU AND JEAN FROMENTIN Abstract. For any positive integer r, we exhibit a nontrivial knot Kr with r− r (20·2 1 +1) crossings whose Jones polynomial V (Kr) is equal to 1 modulo 2 . Our construction rests on a certain 20-crossing tangle T20 which is undetectable by the Kauffman bracket polynomial pair mod 2. 1. Introduction In [6], M. B. Thistlethwaite gave two 2–component links and one 3–component link which are nontrivial and yet have the same Jones polynomial as the corre- sponding unlink U 2 and U 3, respectively. These were the first known examples of nontrivial links undetectable by the Jones polynomial. Shortly thereafter, it was shown in [2] that, for any integer k ≥ 2, there exist infinitely many nontrivial k–component links whose Jones polynomial is equal to that of the k–component unlink U k. -

RASMUSSEN INVARIANTS of SOME 4-STRAND PRETZEL KNOTS Se

Honam Mathematical J. 37 (2015), No. 2, pp. 235{244 http://dx.doi.org/10.5831/HMJ.2015.37.2.235 RASMUSSEN INVARIANTS OF SOME 4-STRAND PRETZEL KNOTS Se-Goo Kim and Mi Jeong Yeon Abstract. It is known that there is an infinite family of general pretzel knots, each of which has Rasmussen s-invariant equal to the negative value of its signature invariant. For an instance, homo- logically σ-thin knots have this property. In contrast, we find an infinite family of 4-strand pretzel knots whose Rasmussen invariants are not equal to the negative values of signature invariants. 1. Introduction Khovanov [7] introduced a graded homology theory for oriented knots and links, categorifying Jones polynomials. Lee [10] defined a variant of Khovanov homology and showed the existence of a spectral sequence of rational Khovanov homology converging to her rational homology. Lee also proved that her rational homology of a knot is of dimension two. Rasmussen [13] used Lee homology to define a knot invariant s that is invariant under knot concordance and additive with respect to connected sum. He showed that s(K) = σ(K) if K is an alternating knot, where σ(K) denotes the signature of−K. Suzuki [14] computed Rasmussen invariants of most of 3-strand pret- zel knots. Manion [11] computed rational Khovanov homologies of all non quasi-alternating 3-strand pretzel knots and links and found the Rasmussen invariants of all 3-strand pretzel knots and links. For general pretzel knots and links, Jabuka [5] found formulas for their signatures. Since Khovanov homologically σ-thin knots have s equal to σ, Jabuka's result gives formulas for s invariant of any quasi- alternating− pretzel knot. -

Deep Learning the Hyperbolic Volume of a Knot

Physics Letters B 799 (2019) 135033 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Physics Letters B www.elsevier.com/locate/physletb Deep learning the hyperbolic volume of a knot ∗ Vishnu Jejjala a,b, Arjun Kar b, , Onkar Parrikar b,c a Mandelstam Institute for Theoretical Physics, School of Physics, NITheP, and CoE-MaSS, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, WITS 2050, South Africa b David Rittenhouse Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania, 209 S 33rd Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: An important conjecture in knot theory relates the large-N, double scaling limit of the colored Jones Received 8 October 2019 polynomial J K ,N (q) of a knot K to the hyperbolic volume of the knot complement, Vol(K ). A less studied Accepted 14 October 2019 question is whether Vol(K ) can be recovered directly from the original Jones polynomial (N = 2). In this Available online 28 October 2019 report we use a deep neural network to approximate Vol(K ) from the Jones polynomial. Our network Editor: M. Cveticˇ is robust and correctly predicts the volume with 97.6% accuracy when training on 10% of the data. Keywords: This points to the existence of a more direct connection between the hyperbolic volume and the Jones Machine learning polynomial. Neural network © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY license 3 Topological field theory (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). -

Stability and Triviality of the Transverse Invariant from Khovanov Homology

STABILITY AND TRIVIALITY OF THE TRANSVERSE INVARIANT FROM KHOVANOV HOMOLOGY DIANA HUBBARD AND CHRISTINE RUEY SHAN LEE Abstract. We explore properties of braids such as their fractional Dehn twist coefficients, right- veeringness, and quasipositivity, in relation to the transverse invariant from Khovanov homology defined by Plamenevskaya for their closures, which are naturally transverse links in the standard contact 3-sphere. For any 3-braid β, we show that the transverse invariant of its closure does not vanish whenever the fractional Dehn twist coefficient of β is strictly greater than one. We show that Plamenevskaya's transverse invariant is stable under adding full twists on n or fewer strands to any n-braid, and use this to detect families of braids that are not quasipositive. Motivated by the question of understanding the relationship between the smooth isotopy class of a knot and its transverse isotopy class, we also exhibit an infinite family of pretzel knots for which the transverse invariant vanishes for every transverse representative, and conclude that these knots are not quasipositive. 1. Introduction Khovanov homology is an invariant for knots and links smoothly embedded in S3 considered up to smooth isotopy. It was defined by Khovanov in [Kho00] to be a categorification of the Jones polynomial. Khovanov homology and related theories have had numerous topological applications, including a purely combinatorial proof due to Rasmussen [Ras10] of the Milnor conjecture (for other applications see for instance [Ng05] and [KM11]). In this paper we will consider Khovanov homology calculated with coefficients in Z and reduced Khovanov homology with coefficients in Z=2Z. -

The Conway Knot Is Not Slice

THE CONWAY KNOT IS NOT SLICE LISA PICCIRILLO Abstract. A knot is said to be slice if it bounds a smooth properly embedded disk in B4. We demonstrate that the Conway knot, 11n34 in the Rolfsen tables, is not slice. This com- pletes the classification of slice knots under 13 crossings, and gives the first example of a non-slice knot which is both topologically slice and a positive mutant of a slice knot. 1. Introduction The classical study of knots in S3 is 3-dimensional; a knot is defined to be trivial if it bounds an embedded disk in S3. Concordance, first defined by Fox in [Fox62], is a 4-dimensional extension; a knot in S3 is trivial in concordance if it bounds an embedded disk in B4. In four dimensions one has to take care about what sort of disks are permitted. A knot is slice if it bounds a smoothly embedded disk in B4, and topologically slice if it bounds a locally flat disk in B4. There are many slice knots which are not the unknot, and many topologically slice knots which are not slice. It is natural to ask how characteristics of 3-dimensional knotting interact with concordance and questions of this sort are prevalent in the literature. Modifying a knot by positive mutation is particularly difficult to detect in concordance; we define positive mutation now. A Conway sphere for an oriented knot K is an embedded S2 in S3 that meets the knot 3 transversely in four points. The Conway sphere splits S into two 3-balls, B1 and B2, and ∗ K into two tangles KB1 and KB2 . -

Transverse Unknotting Number and Family Trees

Transverse Unknotting Number and Family Trees Blossom Jeong Senior Thesis in Mathematics Bryn Mawr College Lisa Traynor, Advisor May 8th, 2020 1 Abstract The unknotting number is a classical invariant for smooth knots, [1]. More recently, the concept of knot ancestry has been defined and explored, [3]. In my research, I explore how these concepts can be adapted to study trans- verse knots, which are smooth knots that satisfy an additional geometric condition imposed by a contact structure. 1. Introduction Smooth knots are well-studied objects in topology. A smooth knot is a closed curve in 3-dimensional space that does not intersect itself anywhere. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the unknot and a diagram of the positive trefoil knot. Figure 1. A diagram of the unknot and a diagram of the positive trefoil knot. Two knots are equivalent if one can be deformed to the other. It is well-known that two diagrams represent the same smooth knot if and only if their diagrams are equivalent through Reidemeister moves. On the other hand, to show that two knots are different, we need to construct an invariant that can distinguish them. For example, tricolorability shows that the trefoil is different from the unknot. Unknotting number is another invariant: it is known that every smooth knot diagram can be converted to the diagram of the unknot by changing crossings. This is used to define the smooth unknotting number, which measures the minimal number of times a knot must cross through itself in order to become the unknot. This thesis will focus on transverse knots, which are smooth knots that satisfy an ad- ditional geometric condition imposed by a contact structure. -

Altering the Trefoil Knot

Altering the Trefoil Knot Spencer Shortt Georgia College December 19, 2018 Abstract A mathematical knot K is defined to be a topological imbedding of the circle into the 3-dimensional Euclidean space. Conceptually, a knot can be pictured as knotted shoe lace with both ends glued together. Two knots are said to be equivalent if they can be continuously deformed into each other. Different knots have been tabulated throughout history, and there are many techniques used to show if two knots are equivalent or not. The knot group is defined to be the fundamental group of the knot complement in the 3-dimensional Euclidean space. It is known that equivalent knots have isomorphic knot groups, although the converse is not necessarily true. This research investigates how piercing the space with a line changes the trefoil knot group based on different positions of the line with respect to the knot. This study draws comparisons between the fundamental groups of the altered knot complement space and the complement of the trefoil knot linked with the unknot. 1 Contents 1 Introduction to Concepts in Knot Theory 3 1.1 What is a Knot? . .3 1.2 Rolfsen Knot Tables . .4 1.3 Links . .5 1.4 Knot Composition . .6 1.5 Unknotting Number . .6 2 Relevant Mathematics 7 2.1 Continuity, Homeomorphisms, and Topological Imbeddings . .7 2.2 Paths and Path Homotopy . .7 2.3 Product Operation . .8 2.4 Fundamental Groups . .9 2.5 Induced Homomorphisms . .9 2.6 Deformation Retracts . 10 2.7 Generators . 10 2.8 The Seifert-van Kampen Theorem . -

Vortex Knots in Tangled Quantum Eigenfunctions

Vortex knots in tangled quantum eigenfunctions Alexander J Taylor∗ and Mark R Dennisy H H Wills Physics Laboratory, University of Bristol, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TL, UK Tangles of string typically become knotted, from macroscopic twine down to long-chain macro- molecules such as DNA. Here we demonstrate that knotting also occurs in quantum wavefunctions, where the tangled filaments are vortices (nodal lines/phase singularities). The probability that a vortex loop is knotted is found to increase with its length, and a wide gamut of knots from standard tabulations occur. The results follow from computer simulations of random superpositions of degenerate eigen- states of three simple quantum systems: a cube with periodic boundaries, the isotropic 3-dimensional harmonic oscillator and the 3-sphere. In the latter two cases, vortex knots occur frequently, even in random eigenfunctions at relatively low energy, and are constrained by the spatial symmetries of the modes. The results suggest that knotted vortex structures are generic in complex 3-dimensional wave systems, establishing a topological commonality between wave chaos, polymers and turbulent Bose-Einstein condensates. Complexity in physical systems is often revealed in the sion of the Chladni problem to three dimensions. subtle structures within spatial disorder. In particular, the Despite numerous investigations of the physics of di- complex modes of typical 3-dimensional domains are not verse random filamentary tangles, including quantum usually regular, and at high energies behave according to turbulence[9], loop soups[10], cosmic strings in the early the principles of quantum ergodicity[1, 2]. The differ- universe[11], and optical vortices in 3-dimensional laser ences between chaotic and regular wave dynamics can be speckle patterns[14], the presence of knotted structures seen clearly in the Chladni patterns of a vibrating two- in generic random fields has not been previously empha- dimensional plate[2], in which the zeros (nodes) of the sized or systematically studied. -

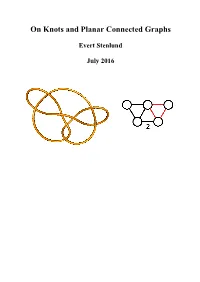

On Knots and Planar Connected Graphs

On Knots and Planar Connected Graphs Evert Stenlund July 2016 1. Introduction If a piece of string is tied and joined at its ends a mathematical knot is formed. In most cases the knot cannot be untied unless the ends are separated again. The field of mathematical knots deals with questions such as whether a knot can be untied or not or whether two knots are the same or not. A lot of efforts have been made in order to answer these questions. [1,2,3] In this note we will discuss how to represent prime knots as planar connected graphs [4]. 2. The trefoil knot The simplest nontrivial knot is the trefoil knot, in which, in its simplest form, the string crosses itself three times. Different versions of this knot are shown in figure 1. Knot 1a can be transformed to coincide with knot 1c, and the knots 1b and 1d have the same relationship. Knot 1b, which is the mirror image of knot 1a, cannot be transformed to coincide with knots 1a or 1c. The trefoil knot has alternating crossings, since, if we follow the string around, the crossings alternate between over- and under-crossings. The trefoil knot is denoted 31 [5]. The knot images shown in this and other figures are drawn using KnotPlot [6]. Figure 1: The trefoil knot 3. The trefoil graphs Figure 2: The trefoil graph I In figure 2 the trefoil knot is deformed to make a connected graph with three nodes and three edges. Firstly the three crossings are squeezed together to make elongated X-es and the rest of the string is rounded off to circles. -

Part 1 Transverse Invariants in Khovanov-Type

MY soul is an entangled knot, Upon a liquid vortex wrought By Intellect, in the Unseen residing, And thine cloth like a convict sit, With marlinspike untwisting it, Only to find its knottiness abiding; Since all the tools for its untying In four-dimensioned space are lying Extract from “A Paradoxical Ode“ by James Clerk Maxwell Contents Introduction iii 1. Links in contact manifolds and effective invariants iii 2. Transverse invariants in Khovanov-Rozansky homologies iv 3. Outline of contents and main results v Part 1. Transverse invariants in Khovanov-type sl2-theories xi Chapter 1. Frobenius algebras and Khovanov-type homologies 1 1. Frobenius algebras 1 2. Link homology theories 7 Chapter 2. Bar-Natan Theory 17 1. The structure of Bar-Natan homology I: the free part 17 2. The structure of Bar-Natan homology II: torsion 31 Chapter 3. Transverse invariants in the sl2-theory 39 1. Transverse knots and braiding 39 2. Transverse invariants from Bar-Natan Homology I: the b-invariant 46 3. Transverse invariants from Bar-Natan Homology II: the invariant c 68 4. Some philosophical remarks 77 Chapter 4. A Bennequin s-inequality from Bar-Natan homology 89 1. A Bennequin s-inequality from the c-invariants 89 2. Comparisons and examples 91 3. Final remarks 100 Part 2. Transverse invariants in sl3-homologies 103 Chapter 5. The universal sl3-link homology via foams 105 1. Webs and Foams 105 2. Foams and Local relations 110 3. The sl3-link homologies via Foams 112 4. Grading and filtration 118 Chapter 6. Transverse invariants in the universal sl3-theory 123 1.