Motif Within the Adventist Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Will There Be a Triple Crown?

Will there be a Triple Crown? SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 2014 732-747-8060 • TDN Home Page Click Here SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 2014 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here SWEEP DREAMS ARE MADE OF THIS THE TAG TEAM At about T-minus 10 minutes in the countdown Yesterday=s G1 Investec Oaks, which was run in towards today=s GI Belmont S., the field will parade memory of Sir Henry Cecil, proved a watershed onto the main track to sounds of Frank Sinatra=s >New moment in the careers of John Gosden, Paul Hanagan York, New York.= It=s reasonable to assume that the and also Sea the Stars (Ire), as Shadwell=s Taghrooda human connections of GI Kentucky Derby and (GB) dominated proceedings to lead home a one-two for GI Preakness S. the Stud and provide her trainer hero California with a first renewal and her jockey Chrome (Lucky and sire with a first Classic of any Pulpit)--heck, kind. All the rage in the ante-post maybe even the market following her emphatic six- horse himself-- length success in Newmarket=s could find certain Listed Pretty Polly S. May 4, the parts of the Taghrooda homebred was eventually let go at a Racing Post Classic tune most generous 5-1 with the operation=s appealing. Lyrics other contender Tarfasha (Ire) (Teofilo {Ire}) more such as: AKing of favored at 9-2. Always traveling with zest behind the California Chrome Horsephotos the hill, top of the leading quartet, the bay tanked down to Tattenham heap.@ Or AA- Corner and, after being allowed to stride to the front number one, head of the list, cream of the crop.@ Well, approaching the quarter pole, opened up to if the chestnut Acan make it there,@ he is Agoing to make comprehensively to best that rival by 3 3/4 lengths. -

FAITHFUL UNDER FIRE: a BIBLE STUDY and DEVOTIONAL for the FILM Introduction

FAITHFUL UNDER FIRE: A BIBLE STUDY AND DEVOTIONAL FOR THE FILM Introduction Hacksaw Ridge, a new film released by Lions Gate Entertainment, Inc., tells the story of Private First Class Desmond Doss, an Army medic who received the nation’s highest award for valor, the Medal of Honor. The MOH decoration is awarded only for conspicuous and personal acts of valor that are unequivocally deemed to be “above and beyond the call of duty.” Desmond Doss was the first conscientious objector to receive that award — and one of only three ever to do so in our Nation’s history. Doss, a Seventh-day Adventist Christian, had a personal, deeply held, biblically formed conviction not to kill — or even to carry a weapon. Nevertheless, he voluntarily enlisted in the Army in 1942 as a combat medic so as to fulfill his calling to serve both his country and his fellow soldiers by saving lives rather than taking them. But a significant part of Desmond’s story is the staunch resistance he faced in the U.S. Army — from both his superiors and fellow soldiers alike, who deemed his non-combatant stance to be a guise for cowardice. The manner in which Doss tenaciously holds-onto his Scripturally based beliefs and ultimately proves himself under the most excruciating and even barbaric combat conditions not only makes for gripping drama. It also confronts everyone who similarly holds biblical convictions in a pluralistic or secular “marketplace” with a challenging roadmap for living faithfully in this world as citizens of our Nation while reserving our highest allegiance to the Kingdom of God. -

138904 03 Dirtmile.Pdf

breeders’ cup dirt mile BREEDERs’ Cup DIRT MILE (GR. I) 7th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS AND UPWARD ONE MILE Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 123 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 120 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile will be limited to twelve (12). If more than twelve (12) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge Winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Dirt Mile (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Alpha Godolphin Racing, LLC Lessee Kiaran P. McLaughlin B.c.4 Bernardini - Munnaya by Nijinsky II - Bred in Kentucky by Darley Broadway Empire Randy Howg, Bob Butz, Fouad El Kardy & Rick Running Rabbit Robertino Diodoro B.g.3 Empire Maker - Broadway Hoofer by Belong to Me - Bred in Kentucky by Mercedes Stables LLC Brujo de Olleros (BRZ) Team Valor International & Richard Santulli Richard C. -

Jebel Ali Raises Curtain on New UAE Season

28 October 2016 www.aladiyat.ae ISSUE 593 Dhs 5 Jebel Ali raises curtain on new UAE season Previews Jebel Ali (Fri) Sharjah (Sat) Cards Pages 50/55 Pages 57/62 28 October 2016 3 Familiar faces with few new names to follow ITH the new season upon Contents us, owners and trainers NEWS 3-21 have clearly completed Wtheir planning ahead of five months UK RACING 22-29 of competition with retained and AUSTRALIAN RACING 31 stable jockeys firmly in place. After a stellar campaign both USA RACING 32-35 domestically and at the Meydan SH MANSOUR FESTIVAL 36-37 Carnival, Champion Trainer Doug BLOODSTOCK 38-43 Watson will again be availing of the services of Pat Dobbs and NICHOLAS GODFREY 44 Sam Hitchcott, while apprentice Adam McLean is also on his Red HOWARD WRIGHT 45 Doug Watson Tadhg O’Shea Stables’ roster. Richard Mullen JOHN BERRY 46 is long established as stable jockey Mansour’s Haajeb in the middle DEREK THOMPSON 47 for Satish Seemar and their round of the Al Maktoum Challenge formidable partnership continues and Sheikh Khalifa’s Abhaar in the MICHELE MACDONALAD 48 with Cameron Noble the latest Emirates Championship. TOM JENNINGS 49 apprentice to grace Zabeel Stables. He is replaced at Millennium PREVIEWS / CARDS Champion Jockey Tadhg O’Shea II Stables, home of Ismail settled in well at Grandstand Mohammed, by ‘The Flying JEBEL ALI (FRIDAY) 50-55 Stables with Ali Rashid Al Rayhi Dutchman’, Adrie de Vries. SHARJAH (SATURDAY) 57-62 last season and is based there again, Erwan Charpy, master of Green while enjoying the opportunity to Stables, has recruited the talents of Editorial ride the cream of Eric Lemartinel’s Antonio Fresu, an Italian whose Purebred Arabians. -

Hacksaw Ridge Partners with DAV

Hacksaw Ridge partners with DAV Film focuses on Medal of Honor recipient, DAV member’s actions, effects of war Andrew Garfield (far right) portrays conscientious objector and Medal of Honor recipient Desmond Doss, credited with carrying 75 injured soldiers one at a time down a cliff face to safety during the Battle of Okinawa. The young medic went on to rescue and render aid to several others in the days that followed, before being seriously wounded himself. (Photo by Mark Rogers © Cross Creek Pictures Pty. Ltd.) Academy Award-winning director Mel Gibson’s newly released film, “Hacksaw Ridge,” will undoubtedly earn millions of dollars at the box office and get plenty of award buzz during its opening weekend, but its impact has the potential to extend well beyond Hollywood. The film is based on the extraordinary true story of late DAV life member Desmond Doss, an Army medic who became the first conscientious objector to be awarded the Medal of Honor. Doss is credited for singlehandedly saving and evacuating 75 wounded men from behind enemy lines, without firing or even carrying a weapon, during World War II’s Battle of Okinawa. “I did a lot of research prior to principal photography because the responsibility I immediately felt taking on the role was palpable,” said Andrew Garfield, who portrayed Doss in the film. “It’s difficult to even attempt to understand who he was and how he was able to do the things that he did with such conviction and bravery and love in his heart through such a horribly violent, traumatizing situation.” While speaking at the 2016 DAV and Auxiliary National Convention in August, Gibson said he intentionally made the battle scenes of the film graphic in order to give viewers a better understanding of the horrors of combat. -

Burlesonincluding Crowley and Joshua MAGAZINE JULY 2014 NOW

BurlesonIncluding Crowley and Joshua MAGAZINE JULY 2014 NOW Her Life is Art Out of a happy place, Kit Hall makes a mark A Visual Masterpiece Seven Miles to Freedom AAtt HHomeome WWithith GGregreg BBradleyr Jr. The Versatile Stripe Taking to the Road In the Kitchen With Raphael Mthombeni www.nowmagazines.com 1 BurlesonNOW July 2014 www.nowmagazines.com 2 BurlesonNOW July 2014 Publisher, Connie Poirier General Manager, Rick Hensley EDITORIAL CONTENTS ,WN[e8QNWOG+UUWG Managing Editor, Becky Walker Burleson Editor, Melissa Rawlins Editorial Coordinator, Sandra Strong Editorial Assistant, Beverly Shay Writers, Lisa Bell . Mark Jameson 8 Erin McEndree . Betty Tryon . Amy Walton Editors/Proofreaders, Pat Anthony Randy Bigham GRAPHICS AND DESIGN Creative Director, Chris McCalla Artists, Eduardo Barajas . Kristin Bato Martha Macias . Felipe Ruiz Brande Morgan . Shannon Pfaff PHOTOGRAPHY Photography Director, Jill Rose Photographers, Jennifer Spears SRC Photography ADVERTISING Advertising Representatives, Melissa McCoy . Lisa Miller . Teresa Banks Rick Ausmus . Linda Dean . Laura Fira Mark Fox . Bryan Frye . Carolyn Mixon Jami Navarro . Cleta Nicholson Lori O’Connell . John Powell . Steve Randle 8 Her Life is Art Linda Roberson Horses inspire this TWU art professor to be an even better teacher. Billing Manager, Angela Mixon Seven Miles to Freedom ON THE COVER 18 Seeking weight loss turned into a motivational tool for Joe Colby. 28 A Visual Masterpiece 18 At Home With Greg Bradley Jr. 44 BusinessNOW Kit Hall preps for painting Lady, one of her five-horse herd. The Versatile Stripe 46 Around TownNOW 36 Both classic and trendy, this design element Photo by SRC Photography. 48 FinanceNOW makes a statement anywhere. -

Life and Death on Hacksaw Ridge

Life and Death on + HACKSAW RIDGE esmond Doss. In Adventist meant he would not carry a gun. He circles, the story of his bravery served in combat in the Pacific, on the Dand how he faced persecution islands of Guam, Leyte, and Okinawa. from fellow soldiers is repeated over His most well-known service was and over. Now, seventy-one years after when Doss was tested in one of the his heroic efforts, the Desmond Doss bloodiest battles during World War story will be shared with the world. II, when his fellow soldiers needed aid Hacksaw Ridge tells the story during the Battle of Okinawa. It was on of Doss’ enlistment and the trials the Maeda Escarpment that Doss ran he faced for taking a stand as a into the fight rather than from it. He is conscientious objector who wanted credited with lowering 75 men to safety to serve his country. Although Doss down the 400-foot escarpment. was a conscientious objector and “Courage and bravery can’t be could have received a draft exemption, taught,” says retired U. S. Army he chose to serve according to the Colonel Charles Knapp and chair of dictates of his conscience, which the Desmond Doss Council. “What 20 many people don’t know about for making the movie changed when Desmond is that before his actions the economy tanked in 2007-2008. on the Maeda Escarpment, he had After that, we had to start completely already been awarded 2 Bronze Stars over.” In February 2015, funding and 2 Purple Hearts. His faith carried was obtained, and the creation of the him through unimaginable horror.” movie was finally underway. -

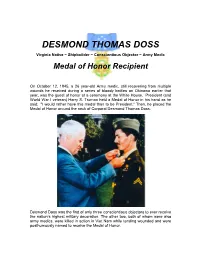

DESMOND-THOMAS-DOSS.Pdf

DESMOND THOMAS DOSS Virginia Native ~ Shipbuilder ~ Conscientious Objector ~ Army Medic Medal of Honor Recipient On October 12, 1945, a 26 year-old Army medic, still recovering from multiple wounds he received during a series of bloody battles on Okinawa earlier that year, was the guest of honor at a ceremony at the White House. President (and World War I veteran) Harry S. Truman held a Medal of Honor in his hand as he said: "I would rather have this medal than to be President." Then, he placed the Medal of Honor around the neck of Corporal Desmond Thomas Doss. Desmond Doss was the first of only three conscientious objectors to ever receive the nation’s highest military decoration. The other two, both of whom were also army medics, were killed in action in Viet Nam while tending wounded and were posthumously named to receive the Medal of Honor. Usually, when people think of Medal of Honor recipients, they picture soldiers rushing into battle with guns blazing. But that description does not fit Desmond Doss. Although he repeatedly rushed into battle, heedless of his own safety, this brave American never carried or fired a weapon. But he was fearless on the battlefield, and more importantly, he also saved an untold number of men's lives. The Medal of Honor is bestowed on members of the armed forces who distinguish themselves through “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his or her life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States”. -

Issue 2 (For Area Codes 434, 757, and 804)

Virginia Veteran November 2018 Page 1 Volume 7, Issue 2 November 2018 Greetings from Staunton! We have Camp Valor Results gone through nearly the first half of By Colonel Denise Loring, USA, (Ret) the year, the weather was interesting, and the amazing work of our VFW Chief Operating Officer (NCR), Camp Valor Outdoors continues. Looking back, I see much was accomplished and I know we will Camp Valor Outdoors connects wounded, injured, and ill continue that going forward. veterans in the outdoors. This is through guided hunting, VFW VA COMMANDER We are excited to welcome our newest fishing, recreational shooting, and competitive shooting. KEN WISEMAN Post on December 8th, 2018. VFW The camp is located in Post 12179 in Lynchburg will be named after Desmond Doss Kingsville, MO, where the who earned the Medal of Honor during WWII as an Army guided hunting, fishing, and Medic. Doss is from Lynchburg. The addition of this Post is archery are primary events. part of a larger goal by the VFW to add some 40 new Posts The competitive shooting this year. We are proud to see Post 12197 be part of that! program is centered in Going forward, we have the second half of the year and a lot Northern Virginia with of work in front of us. We finished the first half with all Quantico and the Fairfax Posts reported in the five categories of community activities Rod & Gun Club being a and I know we can do it again for the second half. We will central base for local shoot- see Voice of Democracy, Patriot’s Pen, and Teacher of the ing. -

B-H Index for 2005 W Cover

INDEX FOR 2005 • VOLUME CXXXI Index, Volume CXXXI January-December, 2005 Abbreviations include: acctg, accounting; adm, administration; adver, Benevolent and Protective Association; IRB, Illinois Racing Board; IRS, advertising; AEI, Average-Earnings Index; agree, agreement; agr, agricul- Internal Revenue Service; JC, Jockey Club; KEEP, Kentucky Equine ture; AI, Artificial Insemination; Am, American; amt, amount; ann, annual; Education Project; KSRC, Kentucky State Racing Commission; KTOB, anniv, anniversary; appt, appointment, appointed; Arg, Argentina; assn, Kentucky Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders; LBSC, Louisiana Breeders association; asst, assistant; attend, attendance; auc, auction; Aust, Sales Company; LSRC, Louisiana State Racing Commission; MHBA, Australian; avg, average; bldstk, bloodstock; BC, Breeders’ Cup; bm, Maryland Horse Breeders Association; MJC, Maryland Jockey Club; MTA, broodmare; bd, board; brdrs, breeders; brdg, breeding; Bute, Butazolidin; Minnesota Thoroughbred Association; MUTBOA, Michigan United c, colt; Can, Canada; CCA, Coaching Club American; CEM, contagious Thoroughbred Breeders and Owners Association; NJTBA, New Jersey equine metritis; chrmn, chairman; champ, champion; co, company; com, Thoroughbred Breeders Association; NTRA, National Thoroughbred Racing committee; comm, commission; conf, conference; conv, convention; corp, Association; NTWA, National Turf Writers Association; NYRA, New York corporation; ct, court; dec, decrease; dept, department; dh, dead heat; dir, Racing Association; NYSRWB, New York -

The Lampette

th 77 INFANTRY DIVISION Reserve Officers Association P.O. Box 604931 Bay Terrace, New York 11360-4931 www.77thinfdivroa.org THE LAMPETTE Editor: BG Robert J. Winzinger, Sr., USA (Ret) Editor Emeritus: BG Harry J. Mott, III, USA (Ret) Summer 2015 Issue 1. THE PRESIDENT’S CORNER: On behalf of the Directors of the Association, I welcome you, our Members, friends, and other readers, to the summer edition of The Lampette. Before getting started, I want to acknowledge the special efforts of BG Bob Winzinger, our Editor, and Mr. Malcolm Schade, for all of their efforts in ensuring that The Lampette publishes on time, is informative, and is made available in both the printed and electronic media. Also, thank you to those who have contributed with their articles. 2015 started out with the deployment of elements of the 389th Combat Sustainment Support Battalion, commanded by LTC Thomas P. Sullivan, a Director of our Association. The Farewell Ceremony for those Soldiers was held in Kaine Hall on 4 January. A number of members of our Association, including MG George E. Barker and BG Robert J. Winzinger, Sr., attended the ceremony, joining the many relatives and friends of the Soldiers who were activated. A report from LTC Sullivan later in this issue indicates that the 389th is being kept busy and is doing very well. Early in the New Year, we lost CW4 Leonard E. Polikoff. Lenny was very active in the Florida Detachment and succeeded BG Russell C. Wright, for whom the Detachment is now officially named, as its leader. In addition to being our communications link with the Detachment, for a number of years Lenny also organized annual cruises which a number of members and spouses enjoyed.