6. Scientists on Stamps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

DUTCH COUNTRY AUCTIONS the Stamp Center Presents PUBLIC AUCTION #329 Now in Our 41St Year

DUTCH COUNTRY AUCTIONS The Stamp Center Presents PUBLIC AUCTION #329 Now In Our 41st Year NEW DATES TUESDAY, & JULY 14, TIMES: WEDNESDAY, 2020 – 10 JULY 15, am ET THURSDAY, 2020 – 10 JULY 16, am ET 2020 – 10 am ET Live Internet Bidding Via Stamp Auction Network See back cover for additional info ORIGINAL DATES & TIMES: Friday, July 17, 2020 – 3 & 5:30 pm ET Saturday, July 18, 2020 – 10 am & 12:30 pm ET 302-478-8740 www.dutchcountryauctions.com 4115 Concord Pike • Wilmington, DE 19803 46900 Dutch Country Auction.pdf1 CONDITIONS OF SALE Bidding 1. The placing of a bid will constitute acceptance of the conditions of sale. 2. All bids are per lot as numbered in the catalog. The right is reserved to withdraw any lot or lots and to group two or more lots. 3. Lots are sold to the highest bidder at one advance over the second highest bid. The auctioneer shall regulate the bidding and in the event of any dispute the auctioneer’s decision shall be final. 4. The auctioneer shall not be liable for errors and omissions in executing instructions to bid. 5. Unlimited bids and bids believed not to be made in good faith will be respectfully declined. 6. Minimum bid on any lot is $50.00. 7. All lots will be sold at the price for which they are knocked down by the auctioneer, plus a commission of 15%. Payment of Purchases 8. Successful bidders will be notified of lots purchased and must remit before lots are delivered. Persons who are known to us may, at our option, have purchases forwarded for immediate payment. -

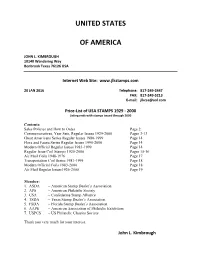

USA Price List (.PDF File)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA JOHN L. KIMBROUGH 10140 Wandering Way Benbrook Texas 76126 USA Internet Web Site: www.jlkstamps.com 20 JAN 2016 Telephone: 817-249-2447 FAX: 817-249-5213 E-mail: [email protected] Price-List of USA STAMPS 1929 - 2000 Listing ends with stamps issued through 2000 Contents: Sales Policies and How to Order Page 2 Commemoratives, Year Sets, Regular Issues 1929-2000 Pages 3-13 Great Americans Series Regular Issues 1980-1999 Page 14 Flora and Fauna Series Regular Issues 1990-2000 Page 14 Modern Official Regular Issues 1983-1999 Page 14 Regular Issue Coil Stamps 1920-2000 Pages 15-16 Air Mail Coils 1948-1976 Page 17 Transportation Coil Series 1981-1995 Page 18 Modern Official Coils 1983-2000 Page 18 Air Mail Regular Issues1926-2000 Page 19 Member: 1. ASDA -- American Stamp Dealer’s Association 2. APS -- American Philatelic Society 3. CSA -- Confederate Stamp Alliance 4. TSDA -- Texas Stamp Dealer’s Association 5. FSDA -- Florida Stamp Dealer’s Association 6. AAPE -- American Association of Philatelic Exhibitors 7. USPCS -- US Philatelic Classics Society Thank you very much for your interest. John L. Kimbrough Sales Policies and How to Order 1. Orders from this USA Listing may be made by mail, FAX, telephone, or E-mail ([email protected]). If you have Internet access, the easiest way to order is to visit my web site (http://www.jlkstamps.com) and use my secure Visa/Mastercard on-line credit card order form. 2. Please order using the Scott Numbers only (may also use a description of the stamp as well). -

View Annual Report

ANNUSKY NETWORKA TLELEVI REPOSION LIMITEDRT JUNE 2013 EVEry Day we’RE ON AN ADVENTURE LESLEY BANKIER FanaticalAS THE about RECEPTIONI Food TV ST I love sweet endings. Whether I’m behind the front desk or attempting recipes from Food TV, I’ll do my best to whip it all into shape and serve it with a smile. COME WITH US EVEry Day we’RE ON AN ADVENTURE FORGING NEW GROUND AND BRINGING CUSTOMERS EXPERIENCES THEY NEVER KNEW EXISTED NADINE WEARING FanaticalAS THE about SENIO SKYR Sport MARKETING EXECUTIVE I’m passionate about getting the right message, to the right person, at the right time. Especially on a Saturday night when the rugby is on SKY Sport. Run it Messam! Straight up the middle! COME WITH US FORGING NEW GROUND AND BRINGING CUSTOMERS EXPERIENCES THEY NEVER KNEW EXISTED TOGETHER WE CAN GO ANYWHERE 7 HIGHLIGHTS 8 CHAIRMAn’S LETTER 10 CHIEF Executive’S REVIEW 14 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 16 BUSINESS OVERVIEW 22 COMMUNITY AND SPONSORSHIP 24 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 30 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 33 2013 FINANCIALS 34 Financial Trends Statement 37 Directors’ Responsibility Statement 38 Income Statement 39 Statement of Comprehensive Income 40 Balance Sheet 41 Statement of Changes in Equity 42 Statement of Cash Flows 43 Notes to the Financial Statements 83 Independent Auditors’ Report 84 OTHER INFORMATION OPENING 86 Corporate Governance Statements 89 Interests Register CREDITS 91 Company and Bondholder Information 95 Waivers and Information 96 Share Market and Other Information 97 Directory 98 SKY Channels SKY Annual Report 2013 6 | HIGHLIGHTS TOTAL REVENUE TOTAL SUBSCRIBERS $885m 855,898 EBITDA ARPU $353m $75.83 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE NET PROFIT $82m $137.2m EMPLOYEES FTEs MY SKY SUBSCRIBERS 1,118 456,419 SKY Annual Report 2013 | 7 “ THE 17-DAY COVERAGE OF THE LONDON OLYMPICS WAS UNPRECEDENTED IN NEW ZEALAND .. -

Assessment Schedule – 2009 History: Examine a Significant Decision Made by People in History, in an Essay (90657) Judgement Statement

NCEA Level 3 History (90657) 2009 — page 1 of 26 Assessment Schedule – 2009 History: Examine a significant decision made by people in history, in an essay (90657) Judgement Statement Achievement Achievement with Merit Achievement with Excellence Through her / his response to the Through her / his response to the Through her / his response to first part of the essay question, the first part of the essay question, the the first part of the essay candidate has accurately candidate has accurately question, the candidate has described factors that contributed explained factors that contributed to accurately and perceptively to the decision. the decision. explained factors that contributed to the decision. (See content guidelines for (See content guidelines for (See content guidelines for examples of relevant historical examples of relevant historical examples of relevant historical information that could be included in information that could be included in information that could be the candidate’s answer.) the candidate’s answer.) included in the candidate’s answer.) Through her / his response to the Through her / his response to the Through the breadth, depth second part of the essay question, second part of the essay question, and / or range of ideas in her / the candidate has accurately the candidate has evaluated the his response to the second described the consequences of the consequences of the decision. part of the question the decision. candidate has comprehensively evaluated (See content guidelines for the consequences of the (See content guidelines for examples of relevant historical decision. examples of relevant historical information that could be included in information that could be included in the candidate’s answer.) the candidate’s answer.) This evaluation should involve the comprehensive weighing This evaluation should involve up of the consequences. -

1946 ~ Former Ref: Second Series M

University Museums and Special Collections Service MAC C C C., H.S. ~ 1878 ~ former ref: 6/60 MAC C&A C&A C. & A. Trading Agencies ~ 1946 ~ former ref: Second series MAC CAB CAB Cabahe, Michael ~ 1909 ~ former ref: 52/58 Caball, John ~ 1953 ~ former ref: Second series Cabaud, Jacques M. ~ 1957 ~ former ref: Second series Cabaut & Cia ~ 1907 ~ former ref: 57/162 Cabaut & Cia ~ 1907 ~ former ref: 203/245 Cabbon, James ~ 1900 ~ former ref: 23/88 Cabburn, John ~ 1945 ~ former ref: Second series University Museums and Special Collections Service Cabell, H.F. ~ 1961 ~ former ref: Second series Cabell, Harold F. ~ 1915 ~ former ref: 69/213 Cabell, William L. ~ 1855 ~ former ref: 224/28 Cable and Wireless Limited ~ 1946, 1956 ~ former ref: Second series Cable, George C. ~ 1947, 1951 ~ former ref: Second series Cable, Herbert ~ 1942 ~ former ref: Second series Cable, John A. ~ 1958 ~ former ref: Second series Cable, Lindsay W. ~ 1942 ~ former ref: Second series Cabran, Auguste ~ 1925 ~ former ref: 88/110 MAC CAC CAC Cachia, Frank ~ 1933 ~ former ref: 152/141 Cacoulides, Libraire C. ~ 1948-61 ~ Booksellers Re: A Greek edition of Composition Excercises in Everyday English by AS Hornby [qv] ~ former ref: Second series University Museums and Special Collections Service MAC CAD CAD Cadbury Bros. Ltd. ~ 1946-62 ~ Chocolate manufacturers Re: The supply of illustrative material for Macmillan titles including The Co-operative Movement at Home and Overseas by Spaull and Kay; Living in Communities Bk II and History Class Pictures; also a request to Macmillan from Cadbu ~ former ref: Second series Cadbury, Geraldine S. ~ 1937 ~ former ref: 179/137 Cadbury, Henry J. -

Postal Bulletin 21993 (3-11-99)

PUBLISHED SINCE MARCH 4, 1880 PB 21993, March 11, 1999 CONTENTS The Postal Bulletin is also available on the World Philately Wide Web at http://www.usps.com for customers Stamp Announcement 99-14: Ayn Rand and at http://blue.usps.gov for employees. Commemorative Stamp. 59 Correction 99-13: Daffy Duck Commemorative Stamp. 61 Correction 99-10: Classroom Flag Definitive ATM Administrative Services Stamp. 61 Correction: Directives and Forms Update Correction. 2 Pictorial Cancellations Announcement. 62 Customer Relations Special Cancellation Die Hubs. 70 Mail Alert. 3 Post Offices Missing Children Posters. 5 Poster Update: Revised Poster 296 Available. 71 Domestic Mail Update: Certification of Invoices Self-Inking Rubber DMM Revision: Correction to Idemnity Claims. 11 Stamp. 71 Reminder: Error in Publication 49. 11 MarketBasket: Ordering MarketBasket Products. 72 DMM Revision: Clarification of Postal Standards: Update: Special Series Post Office Box Locks and Label Carriers, Wrappers, and Printed Features. 12 Keys. 72 PS Form Update: New PS Form 3540-S, Postage Retail Statement Supplement . 13 What’s in Store? . 73 PUB 91 Update: Publication 91, Delivery Confirmation Service Talk: It’s Here. .and We Can Confirm It!. 75 Technical Guide . 16 Update: Retail Merchandising Update. 76 APO/FPO Changes. 16 Your Retail Calendar: March–May 1999 . 81 Notice: Standard Operating Procedures for Accepting Delivery Confirmation Mailings. 17 Postal Bulletin Indexes DMM Revision: Delivery Confirmation Service. 22 Quarterly Index. PB 21984 (11-5-98) Finance Quarterly Index. PB 21984 (11-5-98) Revision: Revision to Handbook F-1, Post Office Ordering Information: Following is the list of postal stock Accounting Procedures . -

Stamp Collecting for Novices – a Brief Booklist

Stamp Collecting for Novices – a Brief Booklist Top Choices for Beginners Encyclopedia of United States stamps and stamp collecting / / Rodney A. Juell & Steven J. Rod, editors; United States Stamp Society. Imprint: Minneapolis, MN: Kirk House Publishers, c2006. Jenny! / / by George Amick. Author: Amick, George Imprint: Sidney, OH: Amos Press, c1986. Linn’s complete stamp collecting basics / / Michael Baadke. Baadke, Michael. Imprint: Sidney, OH: Amos Press, Inc. 2004. Nassau Street / / by Herman Herst, Jr. Herst, Herman. Imprint: Sidney, OH: Amos Press, Inc. c1988 Scott U.S. pocket stamp catalogue / / James Kloetzel (editor) Kloetzel, James. Imprint: Sidney, OH: Scott Publishing Company. Stamp yearbook. United States Postal Service. Imprint: Washington, DC: United States Postal Service, c1998. Catalogs The 1999 comprehensive catalogue of United States stamp booklets: postage and airmail / / Robert Furman. Furman, Robert. Imprint: Iola, WI: Krause Publications, c1999. Brookman stamp price guide / / David S. MacDonald (editor) MacDonald, David S. Imprint: Iola, WI: Krause Publications. Postal Service Guide to U.S. stamps / / U.S. Postal Service Staff. Imprint: Washington, DC: United States Postal Service. Scott standard postage stamp catalogue / / James Kloetzel (editor) Kloetzel, James. Imprint: Sidney, OH: Scott Publishing Company. Scott U.S. pocket stamp catalogue / / James Kloetzel (editor) Kloetzel, James. Imprint: Sidney, OH: Scott Publishing Company. Dictionaries and terminology Definition of terms / / the Expert Committee. Author: Philatelic Foundation (New York, N.Y.). Expert Committee. Publisher: New York, NY: The Philatelic Foundation, 1988. International encyclopaedic dictionary of philatelics / / R. Scott Carlton. Carlton, R. Scott. Imprint: Iola, WI: Krause Publications, c1997. Stamp collecting: philatelic terms illustrated / / James Mackay. Mackay, James A. (James Alexander), 1936. -

1999 Spring USPS Philatelic Catalog

Arctic Fox Polor Bear PUT YOUR STAMP ON HISTORY 1 UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE# usa Philatelic THE OFFICIAL SOURCE FOR STAMP ENTHUSIASTS Dear Stamp Enthusiast, USA PHILATELIC Welcome to USA Philatelic, the official source for current US stamps and The Official Source For Stamp Enthusiasts stamp products. This is the first catalog of the year, and to celebrate we have Spring 1999 several firsts lined up for you. Published by Stamp Services United States Postal Service For a start, with the Victorian-Love stamps (page 4) we have the first stamps Washington, DC 20260-2435 in US postal history cut to the shape of the image. These beautiful 334 and 554 stamps both celebrate the joy of love—and make philatelic history. In this issue we’re Postmaster General and Chief Executive Officer also unveiling two new wildlife stamp issues. Arctic Animals (page 5) depicts creatures William J. Henderson who have adapted to the extreme conditions near the North Pole. And Sonoran Senior Vice President and Desert (page 7), the first in our Nature of America Series, explores the beauty and Chief Marketing Officer diversity of the North American biotic communities. Broadway’s First Couple, Allen R. Kane Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, make their debut on a stamp. And Malcolm X Executive Director, Stamp Services is the latest African American to be honored in the Black Heritage Series. Azeezaly S. Jaffer Manager, International In 1997, the International Collection was introduced as part of the USA Philatelic & Direct Marketing catalog. Since then, the number of countries whose stamps we offer has grown to Richard H. -

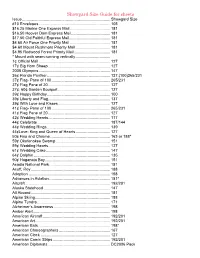

Showgard Size Guide for Sheets Issue

Showgard Size Guide for sheets Issue ................................................................................. Showgard Size #10 Envelopes .................................................................. 105 $16.25 Marine One Express Mail ..................................... 181 $16.50 Hoover Dam Express Mail .................................... 181 $17.50 Old Faithful Express Mail...................................... 181 $4.60 Air Force One Priority Mail ..................................... 181 $4.60 Mount Rushmore Priority Mail ................................ 181 $4.95 Redwood Forest Priority Mail ................................. 181 * Mount with seam running vertically ................................ 1¢ Official Mail .................................................................. 127 17¢ Big Horn Sheep ......................................................... 127 2008 Olympics .................................................................. 147 26¢ Florida Panther .......................................................... 127,(100)265/231 37¢ Flag- Pane of 100 ...................................................... 265/231 37¢ Flag Pane of 20 ......................................................... 127 37¢. 60¢ Garden Bouquet ................................................ 127 39¢ Happy Birthday .......................................................... 100 39¢ Liberty and Flag ......................................................... 137 39¢ With Love and Kisses ............................................... -

1 4 1974 Souvenir Collection of Canada's Standard Postage

NOTE: All of the "The"s & some "A"s have been removed from the Titles. Condition: "F" = Fair, "G" = Good, "E" = Excellent. Date: February 4, 2021 Number Title Author/Edited Cond. By/Description 1 100 Years of Stamp Production (1894-1994) Reprint from the U. S. F Specialist 2 100 Years of Stamp Production (1894-1994) Reprint from the U. S. F Specialist 3 1913-14 Recess Printed Series and the King George Sideface and Australian Philatelic Bureau E Pictorial Definitive Stamps 4 1913-14 Recess-Printed and the King George V Sideface & Australian Post Office E Pictorial Definitive Stamps 5 1913-14 Recess-Printed Series and the King George Sideface and Australian Philatelic Bureau G Pictorial Definitive Stamps 6 1974 Souvenir Collection of Canada's Standard Postage Not Identified E Stamps 7 1975 Canada Specialized Postage Stamp Catalogue Not Identified G 8 1982 Register Rose, Jon E 9 1993 Commemorative Stamp Collection, 1993 U.S. Postal Service E 10 1993 Commemorative Stamp Collection, 1993 U.S. Postal Service E 11 1993 Commemorative Stamp Collection, 1994 U.S. Postal Service E 12 1993 Commemorative Stamp Collection, Elvis Not Identified E 13 1999 Comprehensive Catalogue of United States Stamp Booklets Furman, Robert G 14 19th Century Postage Stamps of the United States, Vol. 1 Brookman, Lester G. G 15 19th Century Postage Stamps of the United States, Vol. 1,1947 Brookman, Lester G. E 16 19th Century Postage Stamps of the United States, Vol. 2, 1947 Brookman, Lester G. G 17 19th Century Postage Stamps of the United States, Vol. 2,1947 Brookman, Lester G. -

Easy to Find?

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County - City Directory Collection - 1939 384 Are You Your name in bold type, under all headings where a buyer might look, referring to a carefully worded descriptive space in this book, to Find? Easy is simply insurance that business will find you. Buttacavoli Angeline tailoress r 1052 Norton Hutz John sec Laffler BYRNE (Gertrude) Engraving Co Inc , Battiste shoe rpr 1052 Norton h do 552 Clinton av N h at Irond Edwd J Rev prof StBernard's Seminary r 2260 Lake Christina studt r 1052 Norton Roy formn 303 State h 108 Vayo Irond Frank r lab 1052 Norton Butzer Ephraim (Flora M) h 112 Rugby av Evelyn M tel opr r 108 Averill av Jos baker r 1052 Norton Marjorie G asst bkpr 47 Main W h 834 Benning Francis r 31 Frost av Mary studt r 1052 Norton ton dr Gr Frank T (Maiy E) v-pres RT Corp 183 Main E rm Buttaccio Francis A (Anna M) asst mgr 14 Franklin Verna M asst bkpr 47 Main W r 834 Bennington 1123 h 312 Roslyn rm 1103 h 163 Augustine dr Gr Fredk A lab r 108 Averill av Jos A (Florence A) h 6 Laura Buxton Lola L wid Fredk G h 1203 Genesee Harrietta L r 178 Magee av Veto A (Margt A) gen agt Manhattan Life Ins Co Robt asst resident surg Strong Memorial Hosp r do Helen r 25 Tracy of N Y 5 StPaul rm 418 h 2325 Clifford av Wm P special agt 183 Main E rm 1004 h 302 Helen E sec 5 StPaul rm 228 r 178 Magee av Buttacovoli John (Jennie) h 58 Ontario Barrington Helen L r 1915 Lake av Buttarazzi Alf mason r 326 Emerson Buyck Ina D Mrs bkpr 121 N Fitzhugh h 1845 Titus Jas J (Lucille) shoe wkr 250 N Goodman r 123 Angelina