CC OO the TASTE of OTHERS NN TT EE Research & Curatorial Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Said Atabekov

Said Atabekov From the series Wolves of the Steppes (Airborne Forces), 2011 Photo print 100 x 150 cm Edition #: 2/5 + 1 AP 1 From the series Wolves of the Steppes, 2013 Photo print 100 x 150 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP 2 From the series Wolves of the Steppes (Janabazar), 2011 Photo print 100 x 150 cm Edition #: 2/5 + 1 AP 3 From the series Wolves of the Steppes (Alpamyskokpar), 2013 Photo print 100 x 150 cm Edition #: 3/5 + 1 AP 4 From the series Steppenwolf, 2013 Photo print 100 x 150 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP 5 From the series Steppenwolf (Arsenal), 2014 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP From the series Steppenwolf (Adidas), 2016 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP 6 From the series Steppenwolf (Airborne Forces), 2014 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP 7 From the series Steppenwolf (Ferrari), 2014 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 2/5 + 1 AP 8 From the series Steppenwolf (GWDC), 2013 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP From the series Steppenwolf (ZSCA KZ), 2016 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP 9 From the series Steppenwolf (Border Control), 2015 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 2/5 + 1 AP 10 From the series Steppenwolf (Aktau Sea Port KZ), 2014 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 1/5 + 1 AP 11 From the series Steppenwolf (Liverpool), 2016 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 2/5 + 1 AP From the series Steppenwolf (Panasonic), 2016 Photo print 105 x 70 cm Edition #: 2/5 + 1 AP 12 Saddle (Oxygen), 2017 wood and car paint 33 x 34 x 47 cm 13 Said Atabekov (b1965) has been acknowledged internationally for his mix of ethnographic signs, recollections of the Russian avant – garde and post – Soviet global interferences. -

Pression” Be a Fair Description?

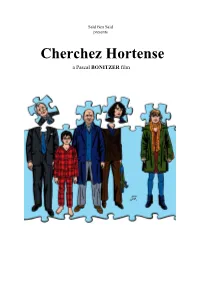

Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense a Pascal BONITZER film Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense A PASCAL BONITZER film Screenplay, adaptation and dialogues by AGNÈS DE SACY and PASCAL BONITZER with JEAN-PIERRE BACRI ISABELLE CARRÉ KRISTIN SCOTT THOMAS with the participation of CLAUDE RICH 1h40 – France – 2012 – SR/SRD – SCOPE INTERNATIONAL PR INTERNATIONAL SALES Magali Montet Saïd Ben Saïd Tel : +33 6 71 63 36 16 [email protected] [email protected] Delphine Mayele Tel : +33 6 60 89 85 41 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Damien is a professor of Chinese civilization who lives with his wife, Iva, a theater director, and their son Noé. Their love is mired in a mountain of routine and disenchantment. To help keep Zorica from getting deported, Iva gets Damien to promise he’ll go to his father, a state department official, for help. But Damien and his father have a distant and cool relationship. And this mission is a risky business which will send Damien spiraling downward and over the edge… INTERVIEW OF PASCAL BONITZER Like your other heroes (a philosophy professor, a critic, an editor), Damien is an intellectual. Why do you favor that kind of character? I know, that is seriously frowned upon. What can I tell you? I am who I am and my movies are also just a tiny bit about myself, though they’re not autobiographical. It’s not that I think I’m so interesting, but it is a way of obtaining a certain sincerity or authenticity, a certain psychological truth. Why do you make comedies? Comedy is the tone that comes naturally to me, that’s all. -

HAGGERTY NEWS Newsletter of the Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Fall 2006, Vol

HAGGERTY NEWS Newsletter of the Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Fall 2006, vol. 20, no. 2 Haggerty Exhibition Explores Work of Emerging Central Asian Artists After the collapse of the Soviet Union, artists from the Central Asian states struggled to reclaim their identity and shape their emerging cultures. The exhibitionArt and Conflict in Central Asia which opens at the Haggerty Museum on Thursday, October 19 focuses on the efforts and aspirations of artists from the states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. The opening lecture will be given in the Museum at 6 p.m. by Valerie Ibraeva, director of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art of Almaty (Kazakhstan), and scholar on Central Asian art. A reception will follow from 7 to 8 p.m. in the Museum. Erbosyn Meldibekov (Kazakhstan), Pol Pot, 2002, photograph The five featured artists are Said Atabekov, Erbossyn Meldibekov, Almagul Menlibayera, Rustan Khalfin and Georgy Tryakin-Bukharov who work Haggerty Exhibition Explores Work of Emerging Central Asian Artists in several mediums relying heavily on video and photography. Over 50 works are included. The history of the region, current conflicts as well as national traditions are all explored by the artists as they strive to express their interpretation of the relation of the Asian states to the rest of the world. Many of the works were shown at the Central Asian Pavilion at the 2005 Venice Biennale. Enrico Mascelloni, one of the foremost authorities on contemporary art of the region, is the co-curator of the exhibition with Valerie Ibraeva. He will assist Lynne Shumow, curator of education, in preparing a series of educational programs in conjunction with the exhibition. -

FIELD MEETING Curatorial Statement and Lineup

Wednesday, October 22 – Sunday, November 2, 2014 Asia Society will host ACAW 2014’s signature program FIELD MEETING: CRITICAL OF THE FUTURE, October 26th & 27th; keynote presentation by Tom Finkelpearl; commissioned performances from Haig Aivazian, Polit-Sheer-Form Office, Bavand Behpoor, and more; 35 art professionals to present latest projects and initiatives; highlighting individual practices, history and institution building in Asia, and subculture cross-pollination. Organized by ACAW director Leeza Ahmady and associate curator Xin Wang CURATORIAL STATEMENT AND LINE-UP INTRODUCTION Inspired by and born of the intense field work carried out by all practitioners of art, FIELD MEETING foregrounds the immediacy of these dynamic exchanges by bringing together over 40 artists, curators, scholars, and institutional leaders whose works variously relate to and problematize the cultural, political, and geographical parameters of contemporary Asia. As a curated platform, FIELD MEETING capitalizes on this fall’s citywide museum and gallery exhibitions shedding light on various aspects of contemporary Asian art through highlighting individual and regional practices; simultaneously, the intensive two-day forum facilitates another Sun Xun, Magician Party and Dead Crow, 2013, installation (wall painting, kind of exchange beyond established ink & color on paper, paper sculpture, and other materials). Courtesy of institutional representation and discourse the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong. to expose the field’s creative practices in a more timely and less mediated fashion. Through lectures, performances, discussions, and most crucially, the presence of the art practitioners both on stage and in the audience, FIELD MEETING presents contemporary art from Asia in its present tense and as a working process that dynamically interacts with creative energies worldwide while challenging its own boundaries. -

Clapping with Stones: Art and Acts of Resistance” Organized by Guest Curator Sara Raza Opens at the Rubin Museum, August 16

For Immediate Release “CLAPPING WITH STONES: ART AND ACTS OF RESISTANCE” ORGANIZED BY GUEST CURATOR SARA RAZA OPENS AT THE RUBIN MUSEUM, AUGUST 16 Featuring works by Lida Abdul; Kader Attia; Nadia Kaabi-Linke; Naiza Khan; Kimsooja; Pallavi Paul; Shahpour Pouyan; Ibrahim Quraishi; Nari Ward; and Hank Willis Thomas Press Preview: August 15, 9:30–11:00 AM Public Opening: August 16, 6:00–11:00 PM For more information: [email protected] July 9, 2019, New York, NY — This August the Rubin Museum of Art is pleased to present the third exhibition in its Year of Power programming, “Clapping with Stones: Art and Acts of Resistance.” Organized by guest curator Sara Raza, the exhibition brings together 10 contemporary artists living and working in the United States and internationally whose works poetically employ non-conformity and resistance as tools to question and upend power in society. Using a range of media — including installation, painting, photography, sculpture, video, and textile — the artists confront history, identity, heritage, and ways of understanding the world at a time when truth is censored, borders reconfigured, mobility impeded, and civil liberties challenged. Bringing together myriad voices, the exhibition presents a meditation on the spirit of defiance expressed through art. “Clapping with Stones: Art and Acts of Resistance” will be on view from August 16, 2019, to January 6, 2020, and will feature works by Lida Abdul, Kader Attia, Nadia Kaabi-Linke, Naiza Khan, Kimsooja, Pallavi Paul, Shahpour Pouyan, Ibrahim Quraishi, Nari Ward, and Hank Willis Thomas. Installed on the sixth floor of the Museum, the exhibition unfolds around Kimsooja’s site- specific installation “Lotus: Zone of Zero” (2019). -

Lida Abdul Biography

ANNA SCHWARTZ GALLERY LIDA ABDUL BIOGRAPHY 1973 Born Kabul, Afghanistan Lives and works in Kabul and Los Angeles EDUCATION 2000 M.F.A., University of California, Irvine 1998 B.A., Philosophy, California State University Fullerton 1997 B.A., Political Science, California State University, Fullerton SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Lida Abdul, Time, Love and the Workings of Anti-Love II, Giorgio Persano Gallery, Progetto Fo.To, Turin, Italy 2015 Lida Adbul, Cap Centre, Lyon 2014 Dhaka Art Summit, Samdani Art Foundation, Bangladesh Lida Abdul, Foundation Calouste|Gulbenkian, Paris 2013 Lida Abdul, CAC Málaga, Spain Videotank #7: Lida Abdul, Foreman Art Gallery, Bishop’s University, Quebec Lida Abdul, What we have overlooked, Galleria Giorgio Persano, Turin, Italy Lida Abdul, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon 2010 Lida Abdul, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon Lida Abdul, MADRE Museum of Contemporary Art, Naples Lida Abdul, Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois The Individual and the War, Ausstellungshalle zeitgenössische Kunst Münster, Münster, Germany Ruins: Stories of Awakening, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne 2009 Moving Perspectives, Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, Washington 2008 Lida Abdul, Galleria Alessandra Bonomo, Rome Lida Abdul, Centre A (Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art) and The Western Front, Vancouver Intimacies of Distant War, Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, State University of New York, New York Lida Abdul, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, USA Memory, -

FOCUS KAZAKHSTAN Thinking Collections: Telling Tales: a Survey Exhibition of Kyzyl Tractor Art Collective

FOCUS KAZAKHSTAN Thinking Collections: Telling Tales: A Survey Exhibition of Kyzyl Tractor Art Collective Signature Program of Asia Contemporary Art Week 2018 Mana Contemporary, Jersey City October 14– 30 November 30, 2018 Curated by Leeza Ahmady and Vladislav Sludskiy Opening Events: Sunday, October 14 Press walkthrough with the curators, 1:30-2:30PM Performance by Kyzyl Tractor, 3PM RSVP [email protected] Kyzyl Tractor Art Collective, Red Bridge of Kyzyl Tractor 2002, archival photo. As part of a documentary film shooting by B. Kairbekov. Courtesy of the artists & Asia Contemporary Art Week 2018 Thinking Collections: Telling Tales: A Survey Exhibition of Kyzyl Tractor Art Collective, a signature program of Asia Contemporary Art Week 2018 at Mana Contemporary, is part of Focus Kazakhstan, a landmark initiative celebrating the art of Kazakhstan through four thematic presentations in London, Berlin, Suwon and Jersey City. This unprecedented survey reunites Kyzyl Tractor collective, known for their feverish experimentations in the mid 1990’s and early 2000’s, after almost two decades of working both separately and occasionally together. The exhibition highlights each artist’s individual practice and contextualizes their work from all periods interacting with one another. The group is acclaimed for reorienting nomadic, Sufi, and Shamanistic philosophies as a new artistic language in juxtaposition with the region’s seismic socio- economic and political shifts. The show comprises two monumental sculptural works - one newly conceived and a reproduction of an older destroyed work - alongside numerous archival photos of the collective’s earlier performances, sculptures, paintings, drawings, found objects and other paraphernalia. On October 14, the opening day of the exhibition, the collective will reenact one of their legendary performance rituals entitled Purification. -

Let It Rain (Parlez-Moi De La Pluie)

LET IT RAIN (PARLEZ-MOI DE LA PLUIE) A FILM DIRECTED BY AGNÈS JAOUI StudioCanal International Marketing 1, place du Spectacle 92863 Issy-les-Moulineaux Cedex 09 Tel. : 33 1 71 35 11 13 Fax : 33 1 71 35 11 86 Les films A4 presents JEAN-PIERRE BACRI JAMEL DEBBOUZE AGNÈS JAOUI LET IT RAIN (PARLEZ-MOI DE LA PLUIE) A FILM WRITTEN BY AGNÈS JAOUI AND JEAN-PIERRE BACRI AND DIRECTED BY AGNÈS JAOUI French release 17 september 2008 98 minutes synopsis Agathe Villanova is a feminist and recent entrant to the political scene. She returns to her childhood home in the South of France to spend ten days helping her sister Florence sort out their mother’s affairs following her death a year earlier. Agathe doesn’t like the region and left it as soon as she could, but for reasons of gender balance in electoral lists, she’s been parachuted back there for the next elections. The house is home to Florence, her husband and her children. There is also Mimouna, the housekeeper whom the Villanovas brought back from Algeria when it became independent. Mimouna’s son, Karim, and his friend Michel Ronsard decide to make a documentary about Agathe Villanova, for a collection of programs on “Successful Women”. It’s August. It’s grey and it’s raining. It’s not normal. But then again, nothing is normal.... interview with agnès jaoui and jean-pierre bacri LET IT RAIN is your third feature film. Did you approach it to make it well up within a sequence shot, so you’re not differently to the first two? aware of the camera’s presence, but at the same it’s still Agnès Jaoui: Yes and no. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Said Atabekov Born 1965 in Bes-Terek, Uzbekistan

www.aspangallery.com Said Atabekov Born 1965 in Bes-Terek, Uzbekistan. He lives and works in Shymkent, Kazakhstan. Education: 1988-1992 Kasteev Shymkent Art College Selected solo exhibitions: 2017 66 Lbs, Andakulova Gallery, Dubai 2016 Steppen Wolves, Esentai Gallery, Almaty 2015 Steppen Wolves, Artwin Gallery, Moscow 2011 Said Atabekov: The Dream of Genghis Khan, Laura Bulian Gallery, Milan 2009 Son of the East, Laura Bulian Gallery, Milan 2007 Way to Rome, Soros Centre for Contemporary Art, Almaty Selected group exhibitions: 2017 Kazakhstan’s National Pavilion at EXPO-2017, Astana Suns and Neons above Kazakhstan, Yarat Contemporary Art Space, Baku Neon Paradise: Shamanism from Central Asia, Laura Bulian Gallery, Milan 2016 TEDxAstana Women It’s about Time, KazMedia Centre, Astana 2015 Fairy Tales, Taipei Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei The Migrant (Moving) Image, A Tale of a Tub, Rotterdam Topografica, American University of Central Asia, Bishkek Arcadia, Kunstvereniging, Diepenheim Walk in Asia, Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo Strategien fur das unplanbare – himmel und himmel GmBH, M45 artspace, Munich Too Early Too Late. Middle East and Modernity, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna 1 www.aspangallery.com 2014 The Other & Me, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah Il Piedistallo vuoto. Fantasmi dall’Est Europa, Museo Civico Archeologico di Bologna, Bologna 777, Tengri-Umai Gallery, Almaty La vie est une légende e.cité – Almaty/Kazakhstan, Museé d’Art Moderne et Contemporain, Strasbourg 2013 More Light, 5th Moscow Biennale 2013, Manege, Moscow Summoning Worlds, -

Mariam Ghani [email protected] Kabul-Reconstructions.Net/Mariam 372 Dekalb Ave

Mariam Ghani [email protected] kabul-reconstructions.net/mariam 372 DeKalb Ave. #3I Brooklyn, NY 11205 tel 718.638.9867 fax 718.398.0894 cell 917.676.8322 E D U C A T I O N & D I S T I N C T I O N S May 2002 MFA summa cum laude in Photography, Video & Related Media, School of Visual Arts Areas of Specialization: Video & the Moving Image; Installation; Computer Arts Distinctions: Aaron Siskind Memorial Scholarship, 2001. January 2000 B.A. summa cum laude with honors in Comparative Literature, New York University. Areas of Specialization: Italian Literature, Visual Studies, Middle Eastern Studies Junior Year Abroad: University of Florence, Italy (Indirizzo: Italianistica) Distinctions: Sir Harold Acton Memorial Scholarship, National Merit Scholarship, Dean’s Undergraduate Research Grant, Italian Departmental Award for Best Student, elected to Phi Beta Kappa in junior year. F E L L O W S H I P S , A W A R D S & R E S I D E N C I E S Akademie Schloss Solitude Fellowship, 2005-07. Smack Mellon Artist in Residence, 2005-06. NYFA Fellowship in Computer Arts, 2005. Eyebeam Atelier Artist in Residence, 2004. Turbulence.org Net Art Commission, 2004. Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Artist in Residence, Woolworth Building, 2003-04. Artist in the Marketplace, Bronx Museum of the Arts, 2002-03. Soros Fellowship for New Americans, 2001-03. R E L E V A N T P R O F E S S I O N A L E X P E R I E N C E Fall 05 Visiting Artist, Art & Technology, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ. -

Sensate Focus (Mark Fell) Y (Sensate Focus 1.666666) [Sensate Focus

Sensate Focus (Mark Fell) Y (Sensate Focus 1.666666) [Sensate Focus / Editions M ego] Tuff Sherm Boiled [Merok] Ital - Ice Drift (Stalker Mix) [Workshop] Old Apparatus Chicago [Sullen Tone] Keith Fullerton Whitman - Automatic Drums with Melody [Shelter Press] Powell - Wharton Tiers On Drums [Liberation Technologies] High Wolf Singularity [Not Not Fun] The Archivist - Answers Could Not Be Attempted [The Archivist] Kwaidan - Gateless Gate [Bathetic Records] Kowton - Shuffle Good [Boomkat] Random Inc. - Jerusalem: Tales Outside The Framework Of Orthodoxy [RItornel] Markos Vamvakaris - Taxim Zeibekiko [Dust-To-Digital] Professor Genius - À Jean Giraud 4 [Thisisnotanexit] Suns Of Arqa (Muslimgauze Re-mixs) - Where's The Missing Chord [Emotional Rescue ] M. Geddes Genras - Oblique Intersection Simple [Leaving Records] Stellar Om Source - Elite Excel (Kassem Mosse Remix) [RVNG Intl.] Deoslate Yearning [Fauxpas Musik] Jozef Van Wissem - Patience in Suffering is a Living Sacrifice [Important Reords ] Morphosis - Music For Vampyr (ii) Shadows [Honest Jons] Frank Bretschneider machine.gun [Raster-Noton] Mark Pritchard Ghosts [Warp Records] Dave Saved - Cybernetic 3000 [Astro:Dynamics] Holden Renata [Border Community] the postman always rings twice the happiest days of your life escape from alcastraz laurent cantet guy debord everyone else olga's house of shame pal gabor billy in the lowlands chilly scenes of winter alambrista david neves lino brocka auto-mates the third voice marcel pagnol vecchiali an unforgettable summer arrebato attila