Barber, String Quartet, Op. 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 4 No. 1, Spring 1988

:.. Chaj)ter of THE INTERNATioNAL VIO~A SOCIETY Association for the Pro motion ofViolaPerforrnance and Research :' Vol. 4 No, 1 .- -. 3 Teaching: Questioning, Imagery and Exploration KathrynPlummer ' 7 Writing for the Viola "·· Alan' Shulman ' .' II ' The Story of Viol~ World .Robert Mandell" (5 William Magers Rosemary Glyde " . ... .", ~ <. ..... .; ~ . The Journal of th e American V iola Society is a public ati on of th at organi zatio n. and is produced at Br igh am You ng U nive rsi ty. w 1985, ISSN 0898-5987. The Jou rn al welcom es letters and art icles fr om its read ers. Editorial off ice : BYU M usic , Ha rr is Fine Arts Ce nte r, Pro vo , UT 84602, (80 1) 378-3083 Editor: David Dalt on Assi stant Ed itor: David Day Advertising off ice : Ha rold K lalZ, 1024 Maple Ave nue , Evanst on , IL 60202, (3 1: ) 869 2972. Dead lin es ar e March J, Ju ne I , and October 1 fo r th e th ree ann ua l issues. Inquir ies can be made to Mr. K latz. Co py and art work sho uld be se nt to th e ed ito r ial office . R ates: $75 full pa ge , 560 two- thi rd s pa ge , 540 half page , 533 o ne- third page , $25 o ne fo urth page. Fo r c lassified s: 510 for 30 wor ds in cl uding ad d ress; $20 for 3 1 to 60 wor d s. Payment to "Arner ica n V iola Soc ie ty" c/o Rose ma ry Gl yde , tr easurer , P.O . -

Joanna Cochenet USA + 1 (402).917.0827 [email protected] Conductor, Clinician, Music Educator Silver Spring, MD 20904

USA + 1 (402).917.0827 JoAnna Cochenet [email protected] Conductor, Clinician, www.joannacochenet.com Music Educator Silver Spring, MD 20904 ORCHESTRAS/ENSEMBLES CONDUCTED IN PERFORMANCE, AUDITION, WORKSHOP, ETC. College, Conservatory, and University Orchestras Bard College Conducting Institute Orchestra (NY) Coe College Concert Band (IA) Coe College Concert Choir (IA) Coe College Pit Orchestra: The Threepenny Opera (IA) Coe College Symphony Orchestra (IA) Coe College Women's Chorale (IA) Levine Music Guitar Orchestra and LA Guitar Quartet (MD) Omaha Conservatory of Music: Baroque Camerata (NE) Omaha Conservatory of Music: Chamber and Pre-Chamber Strings (NE) Omaha Conservatory of Music: Faculty-Student Orchestra (NE) Omaha Premier Lab Orchestra (NE) University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Community Orchestra (WI) University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee String Orchestra (WI) University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra (WI) Washington Conservatory Orchestra (MD) Professional Orchestras Allentown Symphony Small Ensemble (PA) Baltimore Chamber Orchestra (MD) Norwalk Symphony and Pizazz Music (CT) Omaha Symphony Orchestra (NE) Smoky Mountain International Conducting Institute Orchestra (NC) All-City, All-County, Honors, and Youth Orchestras Council Bluffs All-City High School Orchestra (IA) Monroe County Junior High All-County Festival Symphony Orchestra (NY) Northeast String Orchestra (NY) Northeast String Orchestra Advanced Ensemble (NY) Northeast String Orchestra Prelude Strings (NY) Omaha Area Youth Orchestras Prelude Strings (NE) Omaha -

Charles Mcpherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald

Charles McPherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald Generated on Sun, Oct 02, 2011 Date: November 20, 1964 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Carmell Jones (t), Barry Harris (p), Nelson Boyd (b), Albert 'Tootie' Heath (d) a. a-01 Hot House - 7:43 (Tadd Dameron) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! b. a-02 Nostalgia - 5:24 (Theodore 'Fats' Navarro) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! c. a-03 Passport [tune Y] - 6:55 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! d. b-01 Wail - 6:04 (Bud Powell) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! e. b-02 Embraceable You - 7:39 (George Gershwin, Ira Gershwin) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! f. b-03 Si Si - 5:50 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! g. If I Loved You - 6:17 (Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II) All titles on: Original Jazz Classics CD: OJCCD 710-2 — Bebop Revisited! (1992) Carmell Jones (t) on a-d, f-g. Passport listed as "Variations On A Blues By Bird". This is the rarer of the two Parker compositions titled "Passport". Date: August 6, 1965 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Clifford Jordan (ts), Barry Harris (p), George Tucker (b), Alan Dawson (d) a. a-01 Eronel - 7:03 (Thelonious Monk, Sadik Hakim, Sahib Shihab) b. a-02 In A Sentimental Mood - 7:57 (Duke Ellington, Manny Kurtz, Irving Mills) c. a-03 Chasin' The Bird - 7:08 (Charlie Parker) d. -

American Viola Works

Cedille Records CDR 90000 053 AMERICAN VIOLA WORKS Cathy Basrak viola William Koehler Robert Koenig piano music by George Rochberg Frederick Jacobi Alan Shulman Quincy Porter Lowell Liebermann DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 053 AMERICAN VIOLA WORKS GEORGE ROCHBERG: SONATA FOR VIOLA AND PIANO (1979) (20:24) 1 I. Allegro moderato (10:11) 2 II. Adagio lamentoso (7:06) 3 III. Fantasia: Epilogue (2:58) 4 FREDERICK JACOBI: FANTASY FOR VIOLA AND PIANO (1941) (9:47)* 5 ALAN SHULMAN: THEME AND VARIATIONS (1940) (14:02)** 6 QUINCY PORTER: SPEED ETUDE (1948) (2:21)* LOWELL LIEBERMANN: SONATA FOR VIOLA AND PIANO (1984) (25:23)* 7 I. Allegro moderato (8:53) 8 II. Andante (8:57) 9 III. Recitativo (7:24) CATHY BASRAK, VIOLA WILLIAM KOEHLER 4, 7-9 & ROBERT KOENIG 1-3, 5, 6 PIANO *first recording **first recording of original version TT: (72:35) CDCD EFEFEF Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chi- cago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by contributions and grants from individuals, foundations, and corporations, including the WPWR-TV Channel 50 Foundation. PROGRAM NOTES compiled by Cathy Basrak eorge Rochberg (b. 1918) studied rederick Jacobi was born in 1891 G composition at the Mannes School F in San Francisco and died in 1952 of Music and the Curtis Institute. In 1948, in New York. A composition pupil of Rubin he joined the faculty at Curtis, then taught Goldmark and Ernest Bloch, Jacobi served at the University of Pennsylvania, retir- as an assistant conductor of the Metropoli- ing in 1983 as Annenberg Professor of tan Opera and taught composition at Juil- the Humanities Emeritus. -

Notations Spring 2011

The ASCAP Foundation Making music grow since 1975 www.ascapfoundation.org Notations Spring 2011 Tony Bennett & Susan Benedetto Honored at ASCAP Foundation Awards The ASCAP Foundation held its 15th Annual Awards Ceremony at the Allen Room, Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York City on December 8, 2010. Hosted by ASCAP Foundation President, Paul Williams, the event honored vocal legend Tony Bennett and his wife, Susan Benedetto, with The ASCAP Foundation Champion Award in recognition of their unique and significant efforts in arts education. ASCAP Foundation Champion Award recipients Susan Benedetto (l) & Tony Bennett with Mary Rodgers (2nd from left), Mary Ellin A wide variety of ASCAP Foundation Scholarship Barrett (2nd from right), and ASCAP Foundation President Paul and Award recipients were also honored at the Williams (r). event, which included special performances by some of the honorees. For more details and photos of the event, please see our website. Bart Howard provides a Musical Gift The ASCAP Foundation is pleased to announce that composer, lyricist, pianist and ASCAP member Bart Howard (1915-2004) named The ASCAP Foundation as a major beneficiary of all royalties and copyrights from his musical compositions. In line with this generous bequest, The ASCAP Foundation has established programs designed to ensure the preservation of Bart Howard’s name and legacy. These efforts include: Songwriters: The Next Generation, presented by The ASCAP Foundation and made possible by the Bart Howard Estate which showcases the work of emerging songwriters and composers who perform on the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage. The ASCAP Foundation Bart Howard Songwriting Scholarship at Berklee College recog- nizes talent, professionalism, musical ability and career potential in songwriting. -

SSO Mayprogramsp11

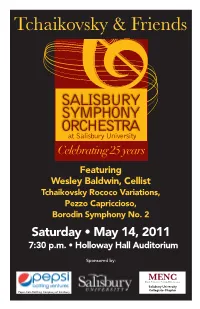

Tchaikovsky & Friends Featuring Wesley Baldwin, Cellist Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations, Pezzo Capriccioso, Borodin Symphony No. 2 Saturday • May 14, 2011 7:30 p.m. • Holloway Hall Auditorium Sponsored by: MENC Music Educators National Conference, Salisbury University Collegiate Chapter Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company of Salisbury Granger & Company, PA CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS 101 WILLIAMSPORT CIRCLE SALISBURY, MARYLAND 21804 T 410.749.5350 F 410.749.9442 www.BatesMoving.com United Van Lines U.S. DOT No. 077949 Gourmet Dining In A Relaxed, Unpretentious Atmosphere With Flawless Service Global Influences National Awards Local Venue New for the 2011-2012 SSO Concert Season Pre-Concert Prix Fixe Dinner for SSO Patrons with Tickets Five Courses for One Price 213 North Fruitland Blvd. 410-677-4880 www.restaurant213.com “A visit here is like a pilgrimage to a shrine of good taste and good tastes. 213 is worth remembering – whether to celebrate a special occasion or, more likely, to make it one.” Mary Lou Baker Chesapeake Life Magazine 2009 James Beard Foundation Honoree 2009, 2010 & 2011 Distinguished Restaurant of North America (1 of 220) WESLEY BALDWIN cello Cellist Wesley Baldwin performs throughout the United States and Europe as soloist and chamber musician. As a soloist he has appeared with conductors including Dan Allcott, James Fellenbaum, Serge Fournier, Cyrus Ginwala, Francis Graffeo, Adrian McDonnell, Daniel Meyer, Jorge Richter, Richard Rosenberg, Brendan Townsend, Kirk Trevor and David Wiley, and with the Laredo Philharmonic, the Oregon Mozart Players, the Symphony of the Mountains, the Bryan Symphony, the Oak Ridge Symphony, and the Wintergreen and Hot Springs Festival orchestras, among others. -

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL 1992-1996 June 4-28, 1992

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL 1992-1996 LOCATION: ROCKPORT ART ASSOCIATION 1992 June 4-28, 1992 Lila Deis, artistic director Thursday, June 4, 1992 GALA OPENING NIGHT CONCERT & CHAMPAGNE RECEPTION New Jersey Chamber Music Society Manhattan String Quartet Trio in C major for flute, violin and cello, Hob. IV: 1 Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Suite No. 6 in D major, BWV 1012 (arr. Benjamin Verdery) Johann Sebastian Bach, (1685-1750) Trio for flute, cello and piano Ned Rorem (1923-) String Quartet in D minor, D. 810 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Friday, June 5, 1992 MUSIC OF THE 90’S Manhattan String Quartet New Jersey Chamber Music Society Towns and Cities for flute and guitar (1991) Benjamin Verdery (1955-) String Quartet in D major, Op. 76, No. 5 Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Quartet in E-flat major for piano and strings, Op. 87 Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) Saturday, June 6, 1992 New Jersey Chamber Music Society Manhattan String Quartet Sonata in F minor for viola and piano, Op. 120, No. 1 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) String Quartet No. 4 Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Trio in E-flat major for piano and strings, Op. 100, D.929 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Sunday, June 7, 1992 SPANISH FIESTA Manhattan String Quartet New Jersey Chamber Music Society With Lila Deis, soprano La Oración del Torero Joaquin Turina (1882-1949) Serenata for flute and guitar Joaquin Rodrigo (1902-) Torre Bermeja Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909) Cordóba (arr. John Williams) Albeniz Siete Canciones Populares Españolas Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) Navarra for two violins and piano, Op. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 16 No. 3, 2000

JOURNAL of the AlVlERICAN VIOLA SOCIETY Section of THE I NTERNATIONAL VIOLA SOCIETY Association for the Promotion ofViola Performance and Research Vol. 16 No.3 2000 FEATURES Joseph Schuberr's Concerto in £-Flat Major By Andrew Levin Cultivating a Private Srudio By Christine Due Orchestral Training Forum: "Wagner's Overtures to Tannhiiuser" By Charles R. Pikfer A Thumb's Decline: To Fuse or Not to Fuse By Dan Whitman From the NS Presidency: "Linkoping Congress Review" By Dwight Pounds OFFICERS Peter Slowik President Professor ofViola Oberlin College Conservatory 13411 Compass Point Strongsville, OH 44136 peter. slowik@oberlin. edu William Preucil II Vice President 317 Windsor Dr. I Iowa City, /A 52245 Catherine Forbes Secretary 1128 Woodland Dr. Arlington, TX 76012 Ellen Rose Treasurer 2807 Lawtherwood Pl. Dallas, TX 75214 Thomas Tatton Past President 7511 Parkwoods Dr. Stockton, C4 95207 BOARD Victoria Chiang Donna Lively Clark Paul Coletti Ralph Fielding Pamela Goldsmith john Graham Barbara Hamilton ~....:::::=:-~-=~11 Karen Ritscher Christine Rutledge -__ -==~~~ ji Kathryn Steely - ! juliet White-Smith Louise Zeitlin EDITOR, JAYS Kathryn Steely Baylor University P.O. Box 97408 "Waco, TX 76798 PAST PRESIDENTS Myron Rosenblum (1971-1981) Maurice W. Riley (1981-1986) David Dalton (1986-1990) Alan de Veritch (1990-1994) HONORARY PRESIDENT William Primrose (deceased) ~ Section ofthe Internationale Viola Society The journal ofthe American Viola Society is a peer-reviewed publication of that organization and is produced at A-R Editions in Madison, Wisconsin. © 2000, American Viola Society ISSN 0898-5987 ]AVS welcomes letters and articles from its readers. Editor: Kathryn Steely Assistant Editor: Jeff A. Steely Assistant Editor for Viola Pedagogy: Jeffrey Irvine Assistant Editor for Interviews: Thomas Tatton Production: A-R Editions, Inc. -

OCT. 30 Chamber Series

OCT. 30 chamber series SEGERSTROM CENTER FOR THE ARTS Samueli Theater 3:00 p.m. presents 2011 –2012 CAFÉ LUDWIG CHAMBER SERIES ORLI SHAHAM • PIANO AND HOST | RAYMOND KOBLER • VIOLIN | BRIDGET DOLKAS • VIOLIN ROBERT BECKER • VIOLA | CAROLYN RILEY • VIOLA | TIMOTHY LANDAUER • CELLO KEVIN PLUNKETT • CELLO | BENJAMIN LULICH • CLARINET | ALAN CHAPMAN • NARRATOR DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH IGOR STRAVINSKY (1906 –1975) Preludes, Op. 34 (1882 –1971) Suite from L’Histoire du Soldat #12 G-sharp minor (The Soldier’s Tale) #2 A minor Marche du soldat (The Soldier’s March) #15 D-flat major Petits airs au bord du ruisseau (Airs by #5 D major a Stream) Orli Shaham Pastorale Marche royale (The Royal March) SERGE PROKOFIEV Petit concert (The Little Concert) (1891 –1953) Musique d’Enfants, Op. 65 Trois danses (Three Dances): #10 March Tango, Valse, Ragtime #2 Promenade Danse du Diable (The Devil’s Dance) #3 Historiette Grand choral (Great Chorale) #4 Tarantelle Marche triomphale du Diable Orli Shaham (Triumphal March of the Devil) Orli Shaham PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Raymond Kobler (1840 –1893) Album pour Enfants, Op. 39 Benjamin Lulich #5 The Toy Soldier’s March Alan Chapman #7 Dolly’s Funeral #8 Waltz #11 Russian Song INTERMISSION #22 The Lark’s Song #13 Kamarinskaja PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Orli Shaham (1840 –1893) Souvenir de Florence • Op. 70, TH 118 Allegro con spirito Adagio cantabile e con moto Allegro moderato Allegro vivace Raymond Kobler Bridget Dolkas Robert Becker Carolyn Riley Timothy Landauer Kevin Plunkett 18 • Pacific Symphony NOTES by michael clive Tchaikovsky’s “Album pour enfants,” translated “Children’s Album,” , was completed and published by the end of that same year, dedicated V to his favorite nephew, 7-year-old Vladimir Davydov — two dozen col - E orful pieces, most of them 30 to 50 bars long, taking less than a I F minute to play. -

Lydia Tang Thesis.Pdf

THE MULTI-FACETED ARTISTRY OF VIOLIST EMANUEL VARDI BY LYDIA M. TANG THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolf Haken, Chair Associate Professor Katherine Syer, Director of Research Associate Professor Scott Schwartz Professor Stephen Taylor Clinical Assistant Professor Elizabeth Freivogel Abstract As a pioneer viola virtuoso of the 20th century, Emanuel “Manny” Vardi (c. 1915-2011) is most widely recognized as the first violist to record all of Paganini’s Caprices. As a passionate advocate for the viola as a solo instrument, Vardi premiered and championed now-standard repertoire, elevated the technique of violists by his virtuosic example, and inspired composers to write more demanding new repertoire for the instrument. However, the details of his long and diverse career have never to date been explored in depth or in a comprehensive manner. This thesis presents the first full biographical narrative of Vardi’s life: highlighting his work with the NBC Symphony under Arturo Toscanini, his activities as a soloist for the United States Navy Band during World War II, his compositional output, visual artwork, an analysis of his playing and teaching techniques, as well as his performing and recording legacies in classical, jazz, and popular music. Appendices include a chronology of his life, discography, lists of compositions written by and for Vardi, registered copyrights, and a list of interviews conducted by the author with family members, former students, and colleagues. -

Toscanini X: Confluence and the Years of Greatness, 1948-1952

Toscanini X: Confluence and the Years of Greatness, 1948-1952 Remarkably, for a conductor who had been before the public since 1886 and had been through several revolutions in musical style as well as conducting style—some of which he pio- neered—Toscanini had one more phase yet to go through. This was his rethinking the “cereal- shot-from-guns” style he had been through and how and where it might be applied to works he already knew as well as works he had yet to conduct or record for the first time. The single most important thing the listener has to come to grips with was that, despite his immense fame and influence on others, Toscanini never thought of himself as an interpreter of music. Many find this claim preposterous since he clearly imposed his personality and the way he heard music on all of his performances, but it happens to be true. “Blessed are the arts who do not need interpreters” was one of his battle-cries, and he included himself in this. He may have thought of himself as the “purest” of conductors because he always strove to get as close to the composers’ original conception of a score even when he tinkered with its structure and/or orches- tration, but tinker he did. What stands in the way of many listeners’ belief that Toscanini consi- dered himself a pure vessel of the composer’s thought is that incredible, almost uncanny energy he brought to everything he conducted. Toscanini’s performances were more, to him as well as to his audiences, than just classical music played by a master. -

Introduction

Introduction Welcome to “The Greatest Hits Explained”. My name is Michael Winter and I’m the host and editor of the show. I’m a German American passionate music lover and I would now like to invite you to go on an exciting musical journey with me. I’m glad you’re here. No matter where you are right now and what you’re doing while you’re listening to this, if you’re in the mood to be entertained by music history, you’ve come to the right place. I’m really looking forward to this journey together. If you like this show, please subscribe, leave a review, a like, a comment – whatever applies to the specific platform on which you’re listening to this. Also, I really appreciate donations. You can find the link on my website or YouTube channel. Those donations help me cover my expenses for this show such as hosting fees, equipment cost, etc. I’m doing all of this to entertain you based on my endless love for music and since there is no big network pumping dollars into this show, I’m the one who has to pay for all related expenses. Therefore, a small donation would already be amazing. Today, we’re gonna talk about one of the most beautiful love songs ever: “Too Young” by the legendary Nat King Cole. I couldn’t be more excited. This song is one of my absolute favorites and I hope you’re interested in hearing a couple of facts about it. “Too Young” is one of those legendary classics that, to many people, is much more than just a song.