NIOSH Alert: Preventing Occupational Exposures to Antineoplastic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Product Characteristics

Health Products Regulatory Authority Summary of Product Characteristics 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT NIPENT 10 mg powder for solution for injection, powder for solution for infusion 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION One vial contains 10 mg Pentostatin. When reconstituted (see Section 6.6), the resulting solution contains pentostatin 2 mg/ml. For a full list of excipients see section 6.1. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Powder for solution for injection, powder for solution for infusion. The vials contain a solid white to off-white cake or powder. The pH of reconstituted solution is 7.0 – 8.2. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic Indications Pentostatin is indicated as single agent therapy in the treatment of adult patients with hairy cell leukaemia. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Pentostatin is indicated for adult patients. Administration to patient It is recommended that patients receive hydration with 500 to 1,000 ml of 5% glucose only or 5% glucose in 0.18% or 0.9% saline or glucose 3.3% in 0.3% saline or 2.5% glucose in 0.45% saline or equivalent before pentostatin administration. An additional 500 ml of 5% glucose only or 5% glucose in 0.18% or 0.9% saline or 2.5% glucose in 0.45% saline or equivalent should be administered after pentostatin is given. The recommended dosage of pentostatin for the treatment of hairy cell leukaemia is 4 mg/m2 in a single administration every other week. Pentostatin may be given intravenously by bolus injection or diluted in a larger volume and given over 20 to 30 minutes. -

LYSODREN Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION -----------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS------------------------ These highlights do not include all the information needed to use • Central Nervous System (CNS) Toxicity: Plasma concentrations LYSODREN safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for exceeding 20 mcg/mL are associated with a greater incidence of toxicity. LYSODREN. (5.2) • Adrenal Insufficiency: Institute steroid replacement as clinically LYSODREN® (mitotane) tablets, for oral use indicated. Measure free cortisol and corticotropin (ACTH) levels to Initial U.S. Approval: 1970 achieve optimal steroid replacement. (5.3) • Embryo-Fetal Toxicity: Can cause fetal harm. Advise women of WARNING: ADRENAL CRISIS IN THE SETTING OF SHOCK OR reproductive potential of the potential risk to a fetus and use of effective SEVERE TRAUMA contraception. (5.4, 8.1, 8.3) See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. • Ovarian Macrocysts in Premenopausal Women: Advise women to seek medical advice if they experience gynecological symptoms such as In patients taking LYSODREN, adrenal crisis occurs in the setting of vaginal bleeding and/or pelvic pain. (5.5) shock or severe trauma and response to shock is impaired. Administer hydrocortisone, monitor for escalating signs of shock and discontinue -------------------------------ADVERSE REACTIONS------------------------------ LYSODREN until recovery. (2.2, 5.1) Common adverse reactions (≥15%) include: anorexia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea; depression, dizziness or vertigo; and rash. (6) ---------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE---------------------------- LYSODREN is an adrenal cytotoxic agent indicated for the treatment of To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Bristol-Myers inoperable, functional or nonfunctional, adrenal cortical carcinoma. (1) Squibb at 1-800-721-5072 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch. -

EDP & Mitotane Protocol

THE CLATTERBRIDGE CANCER CENTRE NHS FOUNDATION TRUST Systemic Anti Cancer Treatment Protocol EDP + mitotane PROCEDURE REF: MPHA HANEDP (Version No: 1.0) Approved for use in: Symptomatic treatment for advanced (unresectable, metastatic or relapsed) adrenocortical carcinoma ECOG performance status of 0 - 2 All possible tumour tissues should be surgically removed from large metastatic masses before mitotane administration is instituted. This is necessary to minimise the possibility of infarction and haemorrhage in the tumour due to a rapid cytotoxic effect of mitotane Exclusion criteria: Previous complete cumulative doses of anthracyclines Decompensated heart failure (ejection fraction <50%) Unstable angina, uncontrolled cardiac arrhythmias, MI or revascularisation procedure within last 6 months Dosage: Drug Dosage Route Frequency Etoposide 100mg/m2 IV Daily on days 2, 3 and 4 of each cycle Doxorubicin 40mg/m2 IV Once only on day 1 of each cycle Cisplatin 40mg/m2 IV Daily on days 3 and 4 of each cycle Variable, max Continuous, started a week prior to IV Mitotane PO 6g daily chemotherapy if not already taking With cycles repeated at 28 day intervals until disease progression Supportive treatments: Domperidone 10mg oral tablets maximum 3 times a day or as required Issue Date: May 2017 Page 1 of 8 Protocol reference: MPHAHANEDP 1 Authorised by: Drugs & Therapeutics Author: Helen Flint Committee & Dr D Husband Version No: 1.0 THE CLATTERBRIDGE CANCER CENTRE NHS FOUNDATION TRUST Extravasation risk: Doxorubicin is a vesicant and must be observed during administration. Follow the procedure for anthracycline extravasation. Erythematous streaking (a histamine release phenomenon) along the vein proximal to the site of injection has been reported, and must be differentiated from an extravasation event. -

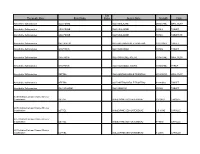

Therapeutic Class Brand Name P a Status Generic

P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 250MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET DR Absorbable Sulfonamides BACTRIM DS SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 800-160MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML SYRUP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 200-40MG/5 ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 400-80MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides SULFADIAZINE SULFADIAZINE 500MG TABLET ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-20MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 2.5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-20MG CAPSULE P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-40MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-40MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 10MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 20MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE -

Cyclophosphamide-Etoposide PO Ver

Chemotherapy Protocol LYMPHOMA CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE-ETOPOSIDE ORAL Regimen Lymphoma – Cyclophosphamide-Etoposide PO Indication Palliative treatment of malignant lymphoma Toxicity Drug Adverse Effect Cyclophosphamide Dysuria, haemorrragic cystitis (rare), taste disturbances Etoposide Alopecia, hyperbilirubinaemia The adverse effects listed are not exhaustive. Please refer to the relevant Summary of Product Characteristics for full details. Patients diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma carry a lifelong risk of transfusion associated graft versus host disease (TA-GVHD). Where blood products are required these patients must receive only irradiated blood products for life. Local blood transfusion departments must be notified as soon as a diagnosis is made and the patient must be issued with an alert card to carry with them at all times. Monitoring Drugs FBC, LFTs and U&Es prior to day one of treatment Albumin prior to each cycle Dose Modifications The dose modifications listed are for haematological, liver and renal function and drug specific toxicities only. Dose adjustments may be necessary for other toxicities as well. In principle all dose reductions due to adverse drug reactions should not be re-escalated in subsequent cycles without consultant approval. It is also a general rule for chemotherapy that if a third dose reduction is necessary treatment should be stopped. Please discuss all dose reductions / delays with the relevant consultant before prescribing, if appropriate. The approach may be different depending on the clinical circumstances. Version 1.1 (Jan 2015) Page 1 of 6 Lymphoma- Cyclophosphamide-Etoposide PO Haematological Dose modifications for haematological toxicity in the table below are for general guidance only. Always refer to the responsible consultant as any dose reductions or delays will be dependent on clinical circumstances and treatment intent. -

©Ferrata Storti Foundation

Malignant Lymphomas Ifosfamide, epirubicin and etoposide (IEV) regimen as salvage and research paper mobilizing therapy for haematologica 2002; 87:816-821 relapsed/refractory lymphoma http://www.haematologica.ws/2002_08/816.htm patients PIER LUIGI ZINZANI, MONICA TANI, ANNA LIA MOLINARI,* VITTORIO STEFONI, ELIANA ZUFFA,* LAPO ALINARI, ANNALISA GABRIELE, FRANCESCA BONIFAZI, Institute of Hematology and Medical Oncology PATRIZIA ALBERTINI, MARZIA SALVUCCI,* SANTE TURA, “L. e A. Seràgnoli”, University of Bologna; MICHELE BACCARANI *Division of Hematology, Ravenna Hospital, Ravenna, Italy Background and Objectives. Therapy for relapsed/refrac- lthough advanced stage Hodgkin’s disease tory lymphomas should be based only on drugs not (HD) and some aggressive non-Hodgkin’s included in the front-line chemotherapy regimens. We Alymphomas (NHL) are potentially curable adopted the strategy of using salvage chemotherapy to with standard chemotherapy, many patients either debulk disease and simultaneously mobilize stem cells, relapse or never achieve remission.1,2 One way of using a regimen based on ifosfamide and etoposide, improving this situation could be to intensify (drugs not usually used for front-line treatment). front-line chemotherapy, either by dose-escala- tion of conventional therapy3 or by adding high- Design and Methods. A three-drug combination of ifos- famide, epirubicin and etoposide (IEV) was used to treat dose chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell 4,5 62 patients with relapsing or refractory aggressive non- (PBSC) rescue. Whereas treatment of relapsing Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL; n=51) or Hodgkin’s disease disease with conventional chemo- and/or radiation (HD; n=11). Forty-five of the patients were studied for the therapy is unsatisfactory, especially in those feasibility of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) harvest. -

PEMD-91-12BR Off-Label Drugs: Initial Results of a National Survey

11 1; -- __...._-----. ^.-- ______ -..._._ _.__ - _........ - t Ji Jo United States General Accounting Office Washington, D.C. 20648 Program Evaluation and Methodology Division B-242851 February 25,199l The Honorable Edward M. Kennedy Chairman, Committee on Labor and Human Resources United States Senate Dear Mr. Chairman: In September 1989, you asked us to conduct a study on reimbursement denials by health insurers for off-label drug use. As you know, the Food and Drug Administration designates the specific clinical indications for which a drug has been proven effective on a label insert for each approved drug, “Off-label” drug use occurs when physicians prescribe a drug for clinical indications other than those listed on the label. In response to your request, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of oncologists to determine: . the prevalence of off-label use of anticancer drugs by oncologists and how use varies by clinical, demographic, and geographic factors; l the extent to which third-party payers (for example, Medicare intermediaries, private health insurers) are denying payment for such use; and l whether the policies of third-party payers are influencing the treatment of cancer patients. We randomly selected 1,470 members of the American Society of Clinical Oncologists and sent them our survey in March 1990. The sam- pling was structured to ensure that our results would be generalizable both to the nation and to the 11 states with the largest number of oncologists. Our response rate was 56 percent, and a comparison of respondents to nonrespondents shows no noteworthy differences between the two groups. -

LEUKERAN 3 (Chlorambucil) 4 Tablets 5

1 PRESCRIBING INFORMATION ® 2 LEUKERAN 3 (chlorambucil) 4 Tablets 5 6 WARNING 7 LEUKERAN (chlorambucil) can severely suppress bone marrow function. Chlorambucil is a 8 carcinogen in humans. Chlorambucil is probably mutagenic and teratogenic in humans. 9 Chlorambucil produces human infertility (see WARNINGS and PRECAUTIONS). 10 DESCRIPTION 11 LEUKERAN (chlorambucil) was first synthesized by Everett et al. It is a bifunctional 12 alkylating agent of the nitrogen mustard type that has been found active against selected human 13 neoplastic diseases. Chlorambucil is known chemically as 4-[bis(2- 14 chlorethyl)amino]benzenebutanoic acid and has the following structural formula: 15 16 17 18 Chlorambucil hydrolyzes in water and has a pKa of 5.8. 19 LEUKERAN (chlorambucil) is available in tablet form for oral administration. Each 20 film-coated tablet contains 2 mg chlorambucil and the inactive ingredients colloidal silicon 21 dioxide, hypromellose, lactose (anhydrous), macrogol/PEG 400, microcrystalline cellulose, red 22 iron oxide, stearic acid, titanium dioxide, and yellow iron oxide. 23 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY 24 Chlorambucil is rapidly and completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. After single 25 oral doses of 0.6 to 1.2 mg/kg, peak plasma chlorambucil levels (Cmax) are reached within 1 hour 26 and the terminal elimination half-life (t½) of the parent drug is estimated at 1.5 hours. 27 Chlorambucil undergoes rapid metabolism to phenylacetic acid mustard, the major metabolite, 28 and the combined chlorambucil and phenylacetic acid mustard urinary excretion is extremely 29 low — less than 1% in 24 hours. In a study of 12 patients given single oral doses of 0.2 mg/kg of 30 LEUKERAN, the mean dose (12 mg) adjusted (± SD) plasma chlorambucil Cmax was 31 492 ± 160 ng/mL, the AUC was 883 ± 329 ng●h/mL, t½ was 1.3 ± 0.5 hours, and the tmax was 32 0.83 ± 0.53 hours. -

Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment Regimens

HODGKIN LYMPHOMA TREATMENT REGIMENS (Part 1 of 5) Clinical Trials: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends cancer patient participation in clinical trials as the gold standard for treatment. Cancer therapy selection, dosing, administration, and the management of related adverse events can be a complex process that should be handled by an experienced health care team. Clinicians must choose and verify treatment options based on the individual patient; drug dose modifications and supportive care interventions should be administered accordingly. The cancer treatment regimens below may include both U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved and unapproved indications/regimens. These regimens are provided only to supplement the latest treatment strategies. These Guidelines are a work in progress that may be refined as often as new significant data become available. The NCCN Guidelines® are a consensus statement of its authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult any NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma1 Note: All recommendations are Category 2A unless otherwise indicated. Primary Treatment Stage IA, IIA Favorable (No Bulky Disease, <3 Sites of Disease, ESR <50, and No E-lesions) REGIMEN DOSING Doxorubicin + Bleomycin + Days 1 and 15: Doxorubicin 25mg/m2 IV push + bleomycin 10units/m2 IV push + Vinblastine + Dacarbazine vinblastine 6mg/m2 IV over 5–10 minutes + dacarbazine 375mg/m2 IV over (ABVD) (Category 1)2-5 60 minutes. -

Cancer Drug Pharmacology Table

CANCER DRUG PHARMACOLOGY TABLE Cytotoxic Chemotherapy Drugs are classified according to the BC Cancer Drug Manual Monographs, unless otherwise specified (see asterisks). Subclassifications are in brackets where applicable. Alkylating Agents have reactive groups (usually alkyl) that attach to Antimetabolites are structural analogues of naturally occurring molecules DNA or RNA, leading to interruption in synthesis of DNA, RNA, or required for DNA and RNA synthesis. When substituted for the natural body proteins. substances, they disrupt DNA and RNA synthesis. bendamustine (nitrogen mustard) azacitidine (pyrimidine analogue) busulfan (alkyl sulfonate) capecitabine (pyrimidine analogue) carboplatin (platinum) cladribine (adenosine analogue) carmustine (nitrosurea) cytarabine (pyrimidine analogue) chlorambucil (nitrogen mustard) fludarabine (purine analogue) cisplatin (platinum) fluorouracil (pyrimidine analogue) cyclophosphamide (nitrogen mustard) gemcitabine (pyrimidine analogue) dacarbazine (triazine) mercaptopurine (purine analogue) estramustine (nitrogen mustard with 17-beta-estradiol) methotrexate (folate analogue) hydroxyurea pralatrexate (folate analogue) ifosfamide (nitrogen mustard) pemetrexed (folate analogue) lomustine (nitrosurea) pentostatin (purine analogue) mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard) raltitrexed (folate analogue) melphalan (nitrogen mustard) thioguanine (purine analogue) oxaliplatin (platinum) trifluridine-tipiracil (pyrimidine analogue/thymidine phosphorylase procarbazine (triazine) inhibitor) -

Chemotherapy in Advanced Ovarian Cancer: an Overview of Randomised Clinical Trials BMJ: First Published As 10.1136/Bmj.303.6807.884 on 12 October 1991

Chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer: an overview of randomised clinical trials BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.303.6807.884 on 12 October 1991. Downloaded from Advanced Ovarian Cancer Trialists Group Abstract cytotoxic drugs, usually doxorubicin and cyclophos- Objectives-To consider the role of platinum and phamide with or without hexamethylmelamine.45 the relative merits of single agent and combination When, however, doubt was cast on the effectiveness chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced ovarian of doxorubicin by both randomised phase III trials6-8 cancer. and phase II studies in patients not responding to Design-Formal quantitative overview using cisplatin9 several major centres adopted cisplatin plus updated individual patient data from all available cyclophosphamide as standard. Furthermore, when randomised trials (published and unpublished). other trials failed to find significant survival differences Subjects-8139 patients (6408 deaths) included in between single agent cisplatin and cisplatin in combi- 45 different trials. nation with other drugs'0 some centres reverted to Results-No firm conclusions could be reached. using single agent platinum as routine first line treat- Nevertheless, the results suggest that in terms of ment. Recently a large number oftrials have compared survival immediate platinum based treatment was cisplatin with its less nephrotoxic and neurotoxic better than non-platinum regimens (overall relative analogue carboplatin, and although follow up times risk 0-93; 95% confidence interval 0-83 to 1-05); were often short, many institutions have now adopted platinum in combination was better than single agent carboplatin as standard. platinum when used in the same dose (overall Currently it is unclear what constitutes optimal relative risk 0-85; 0*72 to 1-00); and cisplatin and chemotherapy for advanced disease and treatment carboplatin were equally effective (overall relative strategies vary both nationally and internationally. -

The Synergic Effect of Vincristine and Vorinostat in Leukemia in Vitro and In

Chao et al. Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2015) 8:82 DOI 10.1186/s13045-015-0176-7 JOURNAL OF HEMATOLOGY & ONCOLOGY RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The synergic effect of vincristine and vorinostat in leukemia in vitro and in vivo Min-Wu Chao1, Mei-Jung Lai2, Jing-Ping Liou3, Ya-Ling Chang1, Jing-Chi Wang4, Shiow-Lin Pan4*† and Che-Ming Teng1*† Abstract Background: Combination therapy is a key strategy for minimizing drug resistance, a common problem in cancer therapy. The microtubule-depolymerizing agent vincristine is widely used in the treatment of acute leukemia. In order to decrease toxicity and chemoresistance of vincristine, this study will investigate the effects of combination vincristine and vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA)), a pan-histone deacetylase inhibitor, on human acute T cell lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Methods: Cell viability experiments were determined by 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, and cell cycle distributions as well as mitochondria membrane potential were analyzed by flow cytometry. In vitro tubulin polymerization assay was used to test tubulin assembly, and immunofluorescence analysis was performed to detect microtubule distribution and morphology. In vivo effect of the combination was evaluated by a MOLT-4 xenograft model. Statistical analysis was assessed by Bonferroni’s t test. Results: Cell viability showed that the combination of vincristine and SAHA exhibited greater cytotoxicity with an IC50 value of 0.88 nM, compared to each drug alone, 3.3 and 840 nM. This combination synergically induced G2/M arrest, followed by an increase in cell number at the sub-G1 phase and caspase activation.