Steve Cauthen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 March Newsletter

Quarterly Newsletter March 2008 Derrinstown Derby & Guineas Trial 11th May Derrinstown Stud Apprentice Series 2008 The Derrinstown Derby and Guineas Trials will again be held a Leopardstown Racecourse on the 11th May 2008. This derrinstownderrinstown highly enjoyable day features the G2 Derby Trial and G3 Guineas Trials both proudly sponsored by Derrinstown. The trials give us an indication of the possible hopefuls for the Epsom/Irish Derbys and also the Guineas. Last years Derby Trial was won by ARCHIPENKO, who despite not running up to expectations in 2007, digest recently won the G2 Al Fahidi Fort at the 2008 Dubai Carnival. The Guineas Trial was won by ALEXANDER TANGO digest who went on to win the G1 Garden City Stakes in the US. Her dam, House In Woods was a recent sales topper at Tat- tersalls February sale and sold for £450,000gns. ALHAARTH BAHRI ELNADIM INTIKHAB MARJU The Derrinstown Stud Apprentice Series 2008 kicks off in April. Last year AMY PARSONS was crowned champion of the series, with Shane Foley and Paul Townend taking second and third spot respectively. Amy received a ladies watch and prize bonds to the value of €2000. The winning trainer, Pat Morris, received his cheque for €1500 with Joanna Morgan and Adrian McGuiness taking the runner up spots. We look forward to seeing Amy’s DOUBLE ECLIPSE FOR career progress in 2008 and wait with anticipation to see who will be crowned the winning apprentice in 2008. SHADWELL New Arrivals at Derrinstown & Shadwell It was a night to remember for Shadwell on Tuesday 22nd January at the 37th Annual KHULOOD (Storm Cat ex Elle Seule) Ch Colt by Pivotal on 22nd January—Visiting Haafhd MOON’S WHISPER (Storm Cat ex East of The Moon) Bay Filly by Pivotal on 4th February —Visiting Oasis Dream Eclipse Awards. -

Juddmonte Farms Limited Annual Report for the Year Ended 31

Registered Number 01746568 Juddmonte Farms Limited Annual Report for the year ended 31 December2018 Juddmonte Farms Limited Annual Report for the year ended 31 December 2018 Page(s) Strategic report 1 - 2 Directors’ report 3 - 4 Independent auditors’ report 5 - 8 Consolidated profit and loss account 9 Consolidated balance sheet 10 Company balance sheet 11 Consolidated and company statement of changes in equity 12 Consolidated statement of cash flows 13 Company statement of cash flows 14 Notes to the financial statements 15 — 38 Juddmonte Farms Limited 1 Strategic Report for the year ended 31 December 2018 Review of business and future developments The directors consider the profit and loss result, turnover and net debt (defined as cash balances less any internal and external borrowings) to be the key performance indicators for the company. The results for the group show a profit before taxation of £9.5 million (2017: £9.9 million) for the year and turnover of £68.8 million (2017: £63.6 million). The group has net debt of £51.3 million (2017: £51.8 million) and net assets, including long term balances to and from group entities, of £29.8 million (2017: £19.3 million). Turnover has increased in 2018 due to a successful year of racing, with group winners both home and abroad. Stallion nomination income increased again in 2018 as demand for the elite stallions was once again robust and as a result gross profit has grown by 13% year on year. The elite stallions continue to be popular with breeders and average stud fees have increased further in 2019. -

16:00 SATURDAY FEBRUARY 20, 2021 the Neom Turf Cup $1,000,000, 2100M, Turf, NH 4Yo&Up and SH 3Yo&Up 16:35 SATURDAY FEBRU

16:00 SATURDAY FEBRUARY 20, 2021 The Neom Turf Cup $1,000,000, 2100m, Turf, NH 4yo&up and SH 3yo&up Weight Dra # Horse Trainer Owner Jockey (kgs) w Prince Faisal Bin 1 Al Hamdany (IRE) Naif Ahmed 57 Cristan Demuro 2 Khalid Bin A/Aziz Wachtel, G Barber, 2 Channel Maker (CAN) William Mott 57 Joel Rosario 3 R.A. Hill & Reeves Abdullah A. J. Sh. A 3 Emirates Knight (IRE) H. Alshuwaib 57 Alexis Moreno 10 Almutairi Mickael 4 For The Top (ARG) Salem bin Ghadayer RRR Racing 57 11 Barzalona Abdulaziz Bin Khalid Mishrif Bin 5 Gronkowski (USA) 57 Olivier Peslier 7 Mishref Shanan 6 Kuwait Currency (USA) Yousef Almutairi Alshatri Steble 57 Eddie Castro 5 Dooley 7 Saltonstall (GB) Adrian McGuinness Thoroughbreds & 57 Gavin Ryan 1 Bart O'Sullivan 8 Star Of Wins (IRE) Fawaz Alghriban Al-Ghuraban Stables 57 Camilo Ospina 8 Prince A/Aziz Bin Wigberto 9 Staunch (GB) Salman F. Almandeel 57 4 Fahd Bin A/Aziz Ramos 10 Tilsit (USA) Charlie Hills Juddmonte 57 Ryan Moore 12 Haif Mohammad 11 Four White Socks (GB) Fahad Haif Alqatani 55 Fawaz Wanas 6 Abood Alqhtani Sons Three Mile House & 12 True Self (IRE) Willie Mullins 55 Hollie Doyle 9 OTI Partnership 16:35 SATURDAY FEBRUARY 20, 2021 The stc 1351 Turf Sprint $1,000,000, 1351m, Turf, NH 4yo&up and SH 3yo&up Weight Dra # Horse Trainer Owner Jockey (kgs) w Shaqran Ayyaad Abdullah 1 Captain Von Trapp (USA) Meshari Al-Mutairi 57 4 Almetairi Sons Alfayrouz Lanfranco 2 Dark Power (IRE) Allan M. -

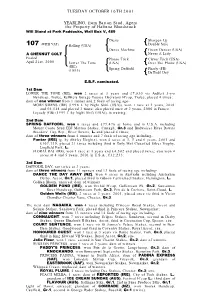

TUESDAY OCTOBER 16TH 2001 YEARLING, from Barton Stud, Agent the Property of Haltuna Bloodstock

TUESDAY OCTOBER 16TH 2001 YEARLING, from Barton Stud, Agent the Property of Haltuna Bloodstock Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Wall Box V, 489 Diesis Sharpen Up 107 (WITH VAT) Halling (USA) Doubly Sure Dance Machine Green Dancer (USA) A CHESNUT COLT Never A Lady Foaled Phone Trick Clever Trick (USA) April 21st, 2000 Lower The Tone (USA) Over The Phone (USA) (IRE) Spring Daffodil Pharly (FR) (1993) Daffodil Day E.B.F. nominated. 1st Dam LOWER THE TONE (IRE), won 2 races at 3 years and £7,830 viz Ardfert 3-y-o Handicap, Tralee, Kellihers Garage Toyota Liberators H'cap, Tralee, placed 4 times; dam of one winner from 1 runner and 2 foals of racing age- MORE SIRENS (IRE) (1998 f. by Night Shift (USA)), won 1 race at 3 years, 2001 and £6,518 and placed 3 times; also placed once at 2 years, 2000 in France. Leyaaly (GB) (1999 f. by Night Shift (USA)), in training. 2nd Dam SPRING DAFFODIL, won 6 races and £79,476 at home and in U.S.A. including Mount Coote Stud EBF Matron Stakes, Curragh, Gr.3 and Budweiser River Downs Breeders' Cup Hcp., River Downs, L. and placed 4 times; dam of three winners from 4 runners and 7 foals of racing age including- Pantar (IRE) (g. by Shirley Heights), won 4 races at 3, 5 and 6 years, 2001 and £107,739, placed 21 times including third in Daily Mail Classified Silver Trophy, Lingfield Park, L. FLORAL RAJ (IRE), won 1 race at 3 years and £4,502 and placed twice; also won 4 races at 4 and 5 years, 2001 in U.S.A., £32,233. -

SHUG MCGAUGHEY $10 Million G1 Dubai World Cup Mar

THURSDAY, 28 JANUARY 2016 RAMSAY: SHOW ME THE DRAMA FASCINATING ROCK HEADS Story and photos by Lucas Marquardt EURO CUP ENTRIES From access to jockeys' and stewards' rooms to employing new technologies like helmet cams, racing can and should do much more to shape a dramatic narrative for television viewers, according to Jim Ramsay, who spoke at the "Racing Media and the 21st Century Fan" panel during Wednesday's second session of the Asian Racing Conference in Mumbai. Ramsay is a director and producer, and has worked for IMG and Channel 4 Racing on such events as the Cheltenham Festival, the Grand National, the Epsom Derby and Royal Ascot. Ramsay's case was simple. Racing has a natural tension and excitement built into it, so why not take advantage of it and use it to create a better entertainment experience? By way of example, he reminded attendees of the 2001 G1 Cox Plate in Australia, which saw eventual winner Northerly (Aus), Sunline (NZ) and Viscount (Aus) finish in a blanket photo after a roughly run final 100 meters. Cont. p3 Champion S. winner Fascinating Rock has been nominated to the G1 Dubai World Cup | Racing Post Newtown Anner Stud homebred Fascinating Rock (Ire) (Fastnet Rock {Aus}) features among the entries for the DOWN THE SHEDROW WITH SHUG MCGAUGHEY $10 million G1 Dubai World Cup Mar. 26, and last year=s = G1 Champion S. winner could try dirt for the first time in the The TDN s Christie DeBernardis chats with Hall of Fame trainer world=s richest race. Shug McGaughey about his potential stable stars for 2016. -

Top Jockey, Trainers and Owner Awards up for Grabs at Royal Ascot

TOP JOCKEY, TRAINER AND OWNER AWARDS UP FOR GRABS AT ROYAL ASCOT 15th June 2020 Awards for leading jockey, trainer and owner will once again be distributed at this year’s Royal Ascot. Frankie Dettori claimed the QIPCO Leading Jockey Award at the Royal Meeting in 2019 with seven victories, thanks largely to a superb four-timer on day three. The 49-year-old looks set to have another excellent book of rides this year as he aims for a seventh title at the meeting. With Jamie Spencer sidelined through injury, Ryan Moore is the only other jockey riding this week to be previously crowned top jockey at Royal Ascot, having claimed the most recent of eight meeting titles in 2018. Due to the protective measures in place this week, there will be no transferable armband for the leading jockey throughout the meeting. Aidan O’Brien received the QIPCO Royal Ascot Leading Trainer Award for a 10th time in 2019 and looks to have his string in top form once again. Other previous winners who will be hoping to have a good week include Sir Michael Stoute, John Gosden, Mark Johnston and Saeed bin Suroor. Paul Cole, who was leading trainer at Royal Ascot in 1994, will aim to create history by becoming the first British-based trainer with a joint-licence to win at the meeting, having gone into partnership with his son Oliver at the start of the season. Simon and Ed Crisford, another father and son combination, will also be looking to saddle the ground-breaking first. -

Juddmonte-Stallion-Brochure-2021

06 Celebrating 40 years of Juddmonte by David Walsh 32 Bated Breath 2007 b h Dansili - Tantina (Distant View) The best value sire in Europe by blacktype performers in 2020 36 Expert Eye 2015 b h Acclamation - Exemplify (Dansili) A top-class 2YO and Breeders’ Cup Mile champion 40 Frankel 2008 b h Galileo - Kind (Danehill) The fastest to sire 40 Group winners in history 44 Kingman 2011 b h Invincible Spirit - Zenda (Zamindar) The Classic winning miler siring Classic winning milers 48 Oasis Dream 2000 b h Green Desert - Hope (Dancing Brave) The proven source of Group 1 speed WELCOME his year, the 40th anniversary of the impact of the stallion rosters on the Green racehorses in each generation. But we also Juddmonte, provides an opportunity to Book is similarly vital. It is very much a family know that the future is never exactly the same Treflect on the achievements of Prince affair with our stallions being homebred to as the past. Khalid bin Abdullah and what lies behind his at least two generations and, in the case of enduring and consistent success. Expert Eye and Bated Breath, four generations. Juddmonte has never been shy of change, Homebred stallions have been responsible for balancing the long-term approach, essential Prince Khalid’s interest in racing goes back to over one-third of Juddmonte’s 113 homebred to achieving a settled and balanced breeding the 1950s. He first became an owner in the Gr.1 winners. programme, with the sometimes difficult mid-1970s and, in 1979, won his first Group 1 decisions that need to be made to ensure an victory with Known Fact in the Middle Park Juddmonte’s activities embrace every stage in effective operation, whilst still competing at Stakes at Newmarket and purchased his first the life of a racehorse from birth to training, the highest level. -

EDITED PEDIGREE for GRACILIA (FR)

EDITED PEDIGREE for GRACILIA (FR) Danzig (USA) Northern Dancer Sire: (Bay 1977) Pas de Nom (USA) ANABAA (USA) (Bay 1992) Balbonella (FR) Gay Mecene (USA) GRACILIA (FR) (Bay 1984) Bamieres (FR) (Bay mare 2009) Bering Arctic Tern (USA) Dam: (Chesnut 1983) Beaune (FR) GREAT NEWS (FR) (Bay 2000) Great Connection (USA) Dayjur (USA) (Bay 1994) Lassie Connection (USA) 2Sx4D Danzig (USA), 5Sx5D Almahmoud, 3Sx5Dx5D Northern Dancer, 3Sx5D Pas de Nom (USA), 4Sx5D Gay Missile (USA) GRACILIA (FR), placed once in France at 3 years and £2,667; Own sister to GREAT EVENT (FR) and GUILLERMO (FR); dam of 2 winners: 2014 CAPITAINE FREGATE (FR) (c. by Fuisse (FR)), won 12 races in Hungary from 2 to 5 years, 2019 and £28,139 and placed 8 times. 2015 MOSSKETEER (GB) (g. by Moss Vale (IRE)), won 1 race at 2 years and £4,201 and placed twice. 2016 Estupendo (GB) (c. by Moohaajim (IRE)), ran once on the flat at 2 years, 2018. 2017 barren to Fast Company (IRE). 2018 (c. by Coach House (IRE)). 2019 (c. by Adaay (IRE)). 1st Dam GREAT NEWS (FR), won 4 races in France at 2 and 3 years and £49,398 including Prix Isola Bella, Maisons-Laffitte, L., placed 4 times including second in Prix Ronde de Nuit, Maisons-Laffitte, L. and third in Prix de Bagatelle, Maisons-Laffitte, L. and Prix des Lilas, Compiegne, L.; dam of 6 winners: GALVESTON (FR) (2010 c. by Green Tune (USA)), won 18 races in France and Morocco from 2 to 7 years and £141,156 and placed 16 times. -

Frankie: the Autobiography of Frankie Dettori Free Download

FRANKIE: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF FRANKIE DETTORI FREE DOWNLOAD Frankie Dettori | 448 pages | 30 Jun 2005 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007176878 | English | London, United Kingdom Frankie Dettori Biography So to have something like this in the Godolphin museum is very good. She knows she is good, and I am trying to enjoy it as much as we all Frankie: The Autobiography of Frankie Dettori. Home Local Classifieds. In total, he has won over 3, races in the UK, and is one of the most celebrated jockeys of all-time, as he has helped the sport reach new levels throughout his career. Dettori was also banned from race for six months at the end of after he tested positive for a banned substance. The inspiration Frankie: The Autobiography of Frankie Dettori the BBC series of the same name. Copy link. Other editions. It's difficult competition on Saturday. Enable: Frankie Dettori tribute as record-breaking horse retired from racing. Asked Quotes I was happy to stay off the pace but when I asked Frankie: The Autobiography of Frankie Dettori to quicken, he went away. Frankie Dettori willing Enable on for historic day in Paris. No crowd. Read more Dettori's self penned summary of his life up to Augustfocusing on his horse racing career, from Italy, via his main career in the UK, to his globe trotting missions for the Godolphin stable. Read more The dream is the third Arc. Home clients further talent our work social media Management contact group. Miriam Todd rated it it was amazing Nov 06, Details if other :. In Skelton was forced into retirement after he broke his neck. -

YEARLING, Consigned by Newsells Park Stud Ltd

YEARLING, consigned by Newsells Park Stud Ltd. Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock P, Box 318 Green Desert (USA) Invincible Spirit (IRE) 366 (WITH VAT) Rafha Kingman (GB) Zamindar (USA) Zenda (GB) A BAY FILLY (GB) Hope (IRE) Foaled Royal Applause (GB) Acclamation (GB) February 18th, 2020 All Out (GB) Princess Athena (first foal) (2015) Mark of Esteem (IRE) Time Over (GB) Not Before Time (IRE) E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. GBB (100%) 1st Dam All Out (GB), won 2 races at 2 years and £36,578 and placed 4 times viz second in Carnarvon Stakes, Newbury, L., third in Sceptre Stakes, Doncaster, Gr.3, Bosra Sham Fillies' Stakes, Newmarket, L. and fourth in Hopeful Stakes, Newmarket, L. She also has a 2021 filly by Showcasing (GB). 2nd Dam TIME OVER (GB), won 1 race at 3 years and placed once, from only 3 starts; dam of four winners from 5 runners and 7 foals of racing age including- Repeater (GB) (g. by Montjeu (IRE)), won 3 races at 2 and 7 years and £99,574, second in Esher Stakes, Sandown Park, L. and third in Doncaster Cup, Doncaster, Gr.2. 3rd Dam NOT BEFORE TIME (IRE), unraced; dam of seven winners from 11 runners and 11 foals of racing age including- TIME AWAY (IRE), won 2 races at 2 and 3 years including Musidora Stakes, York, Gr.3, third in Nassau Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.1, Prix de Diane, Chantilly, Gr.1; dam of winners. TIME ON (GB), 3 races at 3 years at home and in France including Prix de Malleret, Saint-Cloud, Gr.2 and Cheshire Oaks, Chester, L.; dam of MOT JUSTE (USA), 2 races at 2 years including Oh So Sharp Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3. -

YEARLING, Consigned by New England Stud

YEARLING, consigned by New England Stud Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock I, Box 104 Sadler's Wells (USA) Galileo (IRE) 93 (WITH VAT) Urban Sea (USA) Intello (GER) A CHESNUT COLT Impressionnante Danehill (USA) (GB) (GB) Occupandiste (IRE) Foaled Ahonoora Dr Devious (IRE) April 16th, 2015 Hannda (IRE) Rose of Jericho (USA) (2002) Be My Guest (USA) Handaza (IRE) Hazaradjat (IRE) E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st Dam HANNDA (IRE), won 1 race at 3 years and placed once, all her starts; dam of five winners from 6 runners and 7 foals of racing age including- SEAL OF APPROVAL (GB) (2009 f. by Authorized (IRE)), won 4 races at 3 and 4 years and £369,135 including Qipco British Champions Fillies/Mare Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1, EBF Chalice Stakes, Newbury, L., placed 4 times including third in Geoffrey Freer Stakes, Newbury, Gr.3, fourth in Yorkshire Cup, York, Gr.2, Park Hill Stakes, Doncaster, Gr.2. GALE FORCE (GB) (2011 f. by Shirocco (GER)), won 3 races at 4 years, 2015 at home and in France and £45,950 including Prix Denisy, Saint-Cloud, L., placed 6 times including third in Jockey Club Rose Bowl, Newmarket, L. Instance (GB) (2008 f. by Invincible Spirit (IRE)), won 3 races at 2 and 3 years and £34,086 and placed 5 times including third in Oak Tree Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3 and fourth in Sceptre Stakes, Doncaster, Gr.3. FLY (GB) (2012 f. by Pastoral Pursuits (GB)), won 3 races at 3 years, 2015, all her starts. Scoones (GB) (2014 c. -

January Ebn Mon

MONDAY, 23RD NOVEMBER 2020 NEW YEAR NEW OPPORTUNITY JANUARY EBN MON. 11 - THURS. 14 EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • FAX: +44 (0) 1638 666516 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU TODAY’S HEADLINES TATTERSALLS EBN Sales Talk Click here to is brought to contact IRT, or you by IRT visit www.irt.com CHOICE LOTS HIGHLIGHT DECEMBER YEARLING SALE The final yearling sale of the 2020 European sales season gets underway at 11.00am today at Park Paddocks in Newmarket, with over 140 horses on offer at the Tattersalls December Yearling The Tattersalls December Yearling Sale begins at Newmarket Sale. today, with over 140 yearlings due to be offered at the Strict COVID-related protocols remain in place and attendance one-day sale. © Steve Cargill is once again restricted only to those professionally involved in the sale, with internet and telephone bidding through members of the Tattersalls team again available for pre-registered buyers. A Starspangledbanner half-sister to the Gr.1 Cheveley Park IN TODAY’S ISSUE... Stakes winner Alcohol Free (Lot 119) and a Sea The Stars half- TBA AGM report p8 brother to Gr.2 Prix Corrida winner Ambition, out of the Gr.1 Oaks winner Talent (Lot 160), look to be amongst the highlights of the Stakes results p9 catalogue, which includes full/half-siblings to 37 Group or Listed Tattersalls December Yearling Sale pinhooking table p18 winners, including five Gr.1/Classic winners. ADVERTISE t RATED 119 TEN SOVEREIGNS demolishes the opposition in a vintage renewal of the July Cup-Gr.1 defeating Gr.1-winning sprinters Advertise, Fairyland, RATED 122 Pretty Pollyanna, Brando, Limato & Dream Of Dreams t Unbeaten Middle Park Stakes-Gr.1 winner at 2 2021 Fee €20,000 Contact: Coolmore Stud Tel: +353-52-6131298.