Reconstructing Media Culture: Transnational Perspectives on Radio in Silesia, 1924–1948

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Service Broadcasting Resists the Search for Independence in Brazil and Eastern Europe Octavio Penna Pieranti OCTAVIO PENNA PIERANTI

Public Service Broadcasting Resists The search for independence in Brazil and Eastern Europe Octavio Penna Pieranti OCTAVIO PENNA PIERANTI PUBLIC SERVICE BROADCASTING RESISTS The search for independence in Brazil and Eastern Europe Sofia, 2020 Copyright © Author Octavio Penna Pieranti Translation Lee Sharp Publisher Foundation Media Democracy Cover (design) Rafiza Varão Cover (photo) Octavio Penna Pieranti ISBN 978-619-90423-3-5 A first edition of this book was published in Portuguese in 2018 (“A radiodifusão pública resiste: a busca por independência no Brasil e no Leste Europeu”, Ed. FAC/UnB). This edition includes a new and final chapter in which the author updates the situation of Public Service Broadcasting in Brazil. To the (still) young Octavio, who will one day realize that communication goes beyond his favorite “episodes”, heroes and villains Table of Contents The late construction of public communication: two cases ............. 9 Tereza Cruvinel Thoughts on public service broadcasting: the importance of comparative studies ............................................................................ 13 Valentina Marinescu QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS .......................................................... 19 I ........................................................................................................... 21 THE END .............................................................................................. 43 II ........................................................................................................ -

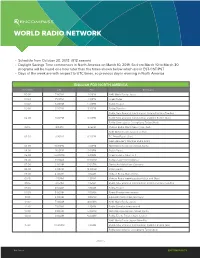

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

2019 List of Awards

List of Awards PRIX EUROPA Best European TV Documentary of the Year 2019 The Raft Sveriges Television - SVT, Sweden Author and Director: Marcus Lindeen, Producer: Erik Gandini 2nd Maelstrom Omroep Human, The Netherlands 3rd The Trial of Ratko Mladic WDR, Germany / International Co-production PRIX EUROPA IRIS Best European TV Programme of the Year 2019 about Cultural Diversity But When Mommy Is Coming? Radiotelevisione svizzera - RSI / SRG SSR, Switzerland Author and Director: Stefano Ferrari, Producer: Michael Beltrami 2nd Back to Rwanda De Chinezen, Belgium 3rd The Sit-in Cinelandia, Sweden PRIX EUROPA Best European Radio Music Programme of the Year 2019 The Man Who Sings From the Heart Polskie Radio S.A., Poland Author and Director: Agnieszka Czyzewska Jacquemet 2nd Ask the Music Professor SR, Sweden 3rd Misia VRT, Belgium 1 List of Awards PRIX EUROPA Best European Radio Investigation of the Year 2019 The Puppet Master BBC, United Kingdom Author, Director and Producer: Neal Razzell 2nd Documentary On One: The Case of Majella Moynihan RTÉ, Ireland 3rd Painkillers NDR, Germany PRIX EUROPA Best European TV Investigation of the Year 2019 MISSION INVESTIGATE: Deceptive Diplomacy SVT, Sweden Author: Ali Fegan, Director and Producer: Axel Gordh Humlesjö 2nd ENVOYÉ SPECIAL: Monsanto Papers, Manufacturing Doubt France Télévisions, France 3rd GREEN WARRIORS: Paraguay’s Poisoned Fields Premières Lignes Télévision, France PRIX EUROPA Best European Radio Documentary Series of the Year 2019 Lord of the Ring Pulls NRK, Norway Author and Director: Grete -

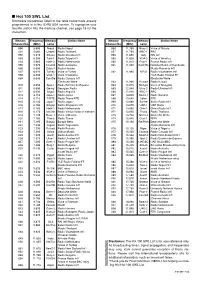

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Ideology of the Air

IDEOLOGY OF THE AIR: COMMUNICATION POLICY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN, 1896-1935 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by SETH D. ASHLEY Dr. Stephanie Craft, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled IDEOLOGY OF THE AIR: COMMUNICATION POLICY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN, 1896-1935 presented by Seth D. Ashley a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ____________________________________________________________ Professor Stephanie Craft ____________________________________________________________ Professor Tim P. Vos ____________________________________________________________ Professor Charles Davis ____________________________________________________________ Professor Victoria Johnson ____________________________________________________________ Professor Robert McChesney For Mom and Dad. Thanks for helping me explore so many different paths. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I entered the master’s program at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, my aim was to become a practitioner of journalism, but the excellent faculty members I worked with helped me aspire to become a scholar. First and foremost is Dr. Stephanie Craft, who has challenged and supported me for more than a decade. I could not have completed this dissertation or this degree without her. I was also fortunate to have early encounters with Dr. Charles Davis and Dr. Don Ranly, who opened me to a world of ideas. More recently, Dr. Tim Vos and Dr. Victoria Johnson helped me identify and explore the ideas that were most important to me. -

Optik TV Channel Listing Guide 2020

Optik TV ® Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver/ Kelowna/ Prince Dawson Victoria/ Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 Alberta Assembly TV ABLEG 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 Citytv Calgary* CKALDT ● ● ● ● ● 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Vancouver* -

Lutherlenin Vysílání Eine Sendung a Broadcasting

Studio 1 Studio 2 Studio 3 #LutherLenin 12:00-13:30 Miroslav Petříček: Confrontage, 500 years Radio Corax and Rádio Papular Prague: Vysílání of modernity (45 min, Czech, English Radio Revolts 1 - Meeting of Czech translation) and German radio activists for the foundation Eine Sendung of a Free Radio Prague Milena Bartlová: How to Share a Revolution? – (90 min, English, Czech translation) A Broadcasting Communication between the educated and the illiterate during Hussitism (45 min, Czech, English translation) 13:40-15:10 A2 collective: What is left of the revolution? Berliner Gazette: Friendly Fire - Reports from Miloš Horanský: Commentary to the Manifesto (90 min, Czech, English translation) the Frontlines of Democracy (3 parts) “The Party of Moderate Progress Within the Part 1: Krystian Woznicki, moderated by Bounds of the Law““ on the last election Sabrina Apitz: What is to be done?, or: Update (90 min, Czech) on the Coming Insurrection (45 min, English, Czech translation) 15:20-16:50 Alexander Tschernek and Tomáš Sedláček: Berliner Gazette: Friendly Fire: Reports from the Natálie Pleváková: Audio broadcasts - Anarchy & Freedom - A Walk Into The Woods Frontlines of Democracy (3 parts) how radio has changed music (90 min, English and German, Czech Part 2: Sazae Bot, moderated by Michael (90 min, Czech) translation) Prinzinger: Anonymous Blockbuster, or: Welcome to the Spectres of a Bot (45 min, English, Czech translation) Part 3: Iskra Geshoska, moderated by Magdalena 2/12/2017 Taube: How to Hijack a Country, or: Do we still Studio Hrdinů Live in the Age of Revolutions? (45 min, English, Prague Czech translation) lenin 500 years of revolution, reformation, media and subject CreWcollective: Delay Observer`s Office CreWcollective: Delay Observer`s Office (directed by: Jan Horák and Roman Štětina) (directed by: Jan Horák and Roman Štětina) 3 scenes, 3 radio stations, 36 hours of programme 17:15-18:45 Ilona Švihlíková and Miroslav Tejkl, moderated Andreas Bernard, moderated by Alexander Stefan Höhne: From Signal to Noise. -

Digital Radio Summit 2014

DIGITAL RADIO SUMMIT 2014 SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Simon Fell, EBU Mr Fell has more than 35 years’ experience in senior broadcasting technology roles, including at British broadcaster ITV, where he was Director of Future Technologies (2008- 2009) and Controller of Emerging Technologies (2004-2006). From 1991-2004 Mr Fell worked for Carlton Television, the ITV franchise holder for the London region, where he held several executive roles linked to operations and emerging technologies. From 15 August he is responsible for steering EBU Technology & Innovation in its mission of being an indispensable partner to EBU Members, driving media innovation and integration, setting standards and defining and sharing best practices in media production and delivery. His role is also involve driving business development for the EBU. Presentation: Welcome to the Digital Radio Summit Annika Nyberg Frankenhaeuser, EBU Annika Nyberg Frankenhaeuser is Director of the EBU Media Department, a role she took up in February 2012. After qualifying as an art teacher at the University of Industrial Arts in Helsinki, she began an enduring relationship with the Swedish Language Services of YLE. Several years as a radio reporter were followed by a move into print, working as an editor for a cultural magazine. In 1986 Ms Nyberg Frankenhaeuser moved from radio at YLE to become a TV reporter for the Swedish Language Services, where she climbed through the television ranks to become Head of TV News & Current Affairs. She was appointed Director of Programmes for Radio in 1997, adding the TV and internet portfolios to her responsibilities in 2006. Ms Nyberg Frankenhaeuser is bilingual in Swedish and Finnish, and fluent in English and German. -

MF Coastal Radio Stations

M.F. Coastal & Maritime Stations 1608 kHz to 4000 kHz This list was last amended 17th September 2008 TX Freq. RX Freq. Mode Callsign Station Name/Frequency Usage Country 1609 2144 SITOR TYA Cotonou Radio Benin 1612 2417 SITOR SUQ Ismaila Radio Egypt 1613 2148 SITOR TYA Cotonou Radio Benin 1614 2149 SITOR SUH El Iskandariya (Alexandria) Radio Egypt 1615 2150 SITOR TYA Cotonou Radio Benin 1615.5 2150.5 SITOR SVH Iraklion Kritis Radio Crete Greece 1618.5 2153.5 SITOR SUK Kosseir Radio Egypt 1621.5 2156.5 DSC LGP Bödo Radio Norway 1621.5 2156.5 DSC National Norwegian Channel Norway 1621.5 2156.5 DSC LGS Svalbard Radio Svalbard 1621.5 2156.5 DSC LGT Tjome Radio Norway 1621.5 2156.5 DSC LGV Vardö Radio Norway 1624.5 2159.5 DSC OXZ Lyngby Radio Denmark 1624.5 2159.5 DSC OXJ Torshavn Radio Faeroe Islands 1627.5 2162.5 DSC Den Helder Rescue Traffic Service Netherlands 1635 2060 SSB LGV Vardö/Hammerfest Radio Norway 1636.4 2045 SSB HZH Jeddah Radio Saudi Arabia 1638 2022 SSB OFK Turku/Vaasa Radio Finland 1641 2045 SSB OXJ Torshavn Radio Faeroe Islands 1641 2066 SSB OXJ Torshavn Radio Faeroe Islands 1642.5 1642.5 SSB Den Helder Rescue (Dutch Coast Guard) Netherlands 1644 2069 SSB EAL Las Palmas/Arrecife Radio Canary Islands 1644 2069 SSB EJM Malin Head Coast Guard Radio Republic of Ireland 1650 2075 SSB TYA Cotonou Radio Benin 1650 Broadcast SSB CROSS Griz-Nez France 1650 Broadcast SSB CROSS Corsen France 1650 Broadcast SSB CROSS Jobourg France 1650 SSB Kardla Piirivalve MRSCC Estonia 1650 SSB Kuressaare Piirivalve MRSCC Estonia 1650 2182 SSB 5VA -

Tribune Internationale Des Compositeurs 2009

Paris, 12.VI.2009 TRIBUNE INTERNATIONALE DES COMPOSITEURS 2009 2009 INTERNATIONAL ROSTRUM OF COMPOSERS Paris, 8 – 12 VI 2009 LISTE FINALE DES PARTICIPANTS / FINAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Président / Chairman : Heikki Valsta (Finlande/Finland) PAYS/ ORGANISME DE RADIODIFFUSION/ DELEGUE(S)/ COUNTRY BROADCASTING ORGANISATION DELEGATE(S) ALLEMAGNE/ Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (sans délégué) GERMANY Deutschlandradio Kultur Rainer PÖLLMANN ARGENTINE/ Radio Universidad Nacional LM María Vanesa RUFFA ARGENTINA AUSTRALIE/ Australian Broadcasting Corporation Duncan YARDLEY AUSTRALIA AUTRICHE/ ORF Austrian Broadcasting Corporation Ursula STRUBINSKY AUSTRIA BRESIL/BRASIL Radio MEC sans délégué/ Without delegate BULGARIE/ Bulgarian National Radio Maria Vassileva POPOVA BULGARIA CANADA Canadian Broadcasting Corporation/ Sans délégué/ Société Radio-Canada Without delegate DANEMARK/ DR- Danish Broadcasting Corporation Max FAGE-PEDERSEN DENMARK ESPAGNE/ Radio Nacional de España Ana Vega TOSCANO SPAIN ESTONIE/ Estonian Public Broadcasting Tiia TEDER ESTONIA FINLANDE/ Finnish Broadcasting Co. Karoliina VESA FINLAND FRANCE Radio France Jurjen SOETING CHINE/HONG KONG SAR/ Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) Man-Ngai TANG CHINA/HONG KONG SAR IRLANDE/ RTÉ Lyric fm Eoin O KELLY IRELAND ISLANDE/ Icelandic National Broadcasting Bergljót HARALDSDÓTTIR ICELAND Service (RUV) LITUANIE/ Lithuanian Radio Jurate KATINAITE LITHUANIA MEXIQUE/ Radio UNAM Alejandro CASTAÑOS MEXICO NORVEGE/ Norwegian Broadcasting Organization Håkon HEGGSTAD NORWAY NOUVELLE ZELANDE/ Radio New Zealand -

SPRING 2018 VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1 TCHCC TOCA Recipients Waymond and Jean Blaha Davis

SPRING 2018 VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1 TCHCC TOCA Recipients Waymond and Jean Blaha Davis Texas Czech Heritage and Cultural Center proudly honored Waymond and Jean Blaha Davis at the 2018 TOCA Awards ceremony. Waymond and Jean are tireless volunteers who are present on a weekly basis helping greet visitors, perform docent duties as well as any other tasks asked of them. Waymond spends many hours in helping maintain the grounds of our ever-growing facility. Pictured left to right: TOCA President Kevin Kana, Jean Blaha Davis, Waymond Davis, and TCHCC President Retta Chandler. Dedicated to the preservation and promotion of the history, language, culture and heritage of Texans of Czech ethnicity.. Náš Český Život OUR MISSION “Our Czech Life” The mission of the TEXAS CZECH HERITAGE AND CULTURAL CEN- TEXAS CZECH HERITAGE AND CULTURAL CENTER TER, INC. is to provide a central facility for the preservation and promo- 250 W. Fairgrounds Road/P. O. Box 6 tion of the history, language, culture and heritage of individuals of Czech La Grange, Texas 78945-0006 ethnicity who can trace their ancestry to the Czechs who immigrated (979) 968-9399 Toll Free (888) 785-4500 from the present day Czech Republic or former Austria-Hungary (in- FAX (979) 968-9249 cluding Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia and Silesia), to honor those immi- Web Page:www.czechtexas.org grants, and to operate exclusively for charitable, scientific, literary and E-mail: [email protected] educational purposes. TCHCC BOARD OF DIRECTORS The goals of the TEXAS CZECH HERITAGE AND CULTURAL Retta Slavik Chandler, Chairman CENTER, INC. are: Joseph Bartosh To educate the public about the past and present contributions and Richard G. -

Aibs 2009 - Shortlisted Entries

AIBs 2009 - shortlisted entries Organisation Country Title Artear (Telenoche - Channel 13) Argentina The Battle at the end of the world ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) Australia Losing Erin ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) Australia Pacific Break VRT Belgium Villa Politica VRT Belgium Verkiezingen 09/Elections 09 Radio Canada Canada Baby Boomers take on Mount Mera Radio Canada Canada Sunday with Darwin Cesky Rozhlas Czech Mokrsko 2008 Republic Czech Radio (Radio Prague) Czech 90 Years of Czechoslovakia - A birthday walk Republic through Prague RFE /RL Czech Afghan Service 'Woman & Life Program' Republic RFE/RL Czech Special coverage of the Azeri referendum Republic Arte France France Tibetan el Dorado France 24 France 15 years after the genocide… France 24 France France 24 - World pioneer on the phone France 24 France Launch of extended broadcast on France 24 Arabic France 24 France The Observers Deutsche Welle Germany Environment - A Paradise under threat - deforestation Deutsche Welle Germany Family affairs - How to become a political player Deutsche Welle Germany On Skis to the North Pole Deutsche Welle Germany Walled In - Germany's inner border Hessischer Rundfunk Germany The Child, the death and the truth NDR Germany Mit 80,000 Fragen um Die Welt… Ridel Communications GmbH & Co KG Germany Riedel MediorNet Riedel Communications GmbH & Co KG Germany Riedel MediorNet WDR Germany Tiananman VTV Satellite Ghana Make me a success enterprise challenge Radio Television Hong Kong Hong Kong Around the World on the Olympic