Major Depressive Disorder in Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

The Effects of Antipsychotic Treatment on Metabolic Function: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

The effects of antipsychotic treatment on metabolic function: a systematic review and network meta-analysis Toby Pillinger, Robert McCutcheon, Luke Vano, Katherine Beck, Guy Hindley, Atheeshaan Arumuham, Yuya Mizuno, Sridhar Natesan, Orestis Efthimiou, Andrea Cipriani, Oliver Howes ****PROTOCOL**** Review questions 1. What is the magnitude of metabolic dysregulation (defined as alterations in fasting glucose, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride levels) and alterations in body weight and body mass index associated with short-term (‘acute’) antipsychotic treatment in individuals with schizophrenia? 2. Does baseline physiology (e.g. body weight) and demographics (e.g. age) of patients predict magnitude of antipsychotic-associated metabolic dysregulation? 3. Are alterations in metabolic parameters over time associated with alterations in degree of psychopathology? 1 Searches We plan to search EMBASE, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE from inception using the following terms: 1 (Acepromazine or Acetophenazine or Amisulpride or Aripiprazole or Asenapine or Benperidol or Blonanserin or Bromperidol or Butaperazine or Carpipramine or Chlorproethazine or Chlorpromazine or Chlorprothixene or Clocapramine or Clopenthixol or Clopentixol or Clothiapine or Clotiapine or Clozapine or Cyamemazine or Cyamepromazine or Dixyrazine or Droperidol or Fluanisone or Flupehenazine or Flupenthixol or Flupentixol or Fluphenazine or Fluspirilen or Fluspirilene or Haloperidol or Iloperidone -

Antipsychotic Medication Reduction

So tonight we'll be discussing antipsychotic medication reduction. I'm happy to share some of my experiences with this challenging initiative and in nursing homes. I have no financial affiliations to disclose. And for our objectives and our agenda today, we're going to assess and evaluate appropriate antipsychotic medication use in nursing home residents, and apply strategies toward behavior management and antipsychotic medication reduction. The first part of the program we'll look at current trends and rates of antipsychotic medication use. We'll discuss the CMS initiative and latest policy issues. And then we'll look at a couple case studies. So first off, this first graph goes over the national progress in reducing the inappropriate use of antipsychotic medications in nursing homes. The taller red bar gives us the 2011 baseline number of 23.9%. That's a dotted red line indicates the start of the 2012 CMS initiative. That's the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes. The latest information all the way down at the end is from the third quarter of 2018, which shows that nationally we have a 14.6% use rate. Overall, this looks like a reduction of nearly 40% since the initiative began. Overall though, I think this is great progress. Why should we be concerned with antipsychotic medications at all in this population? I have to say, that when I first exited my training from psychiatry and geriatric psychiatry, the black box warning had not yet come out. And it hit me that most of all the training that I learned was getting reversed when I entered the care setting. -

Psychotropic Medication Concerns When Treating Individuals with Developmental Disabilities

Tuesday, 2:30 – 4:00, C2 Psychotropic Medication Concerns when Treating Individuals with Developmental Disabilities Richard Berchou 248-613-6716 [email protected] Objective: Identify effective methods for the practical application of concepts related to improving the delivery of services for persons with developmental disabilities Notes: Medication Assistance On-Line Resources OBTAINING MEDICATION: • Needy Meds o Needymeds.com • Partnership for Prescriptions Assistance o Pparx.org • Patient Assistance Program Center o Rxassist.org • Insurance coverage & Prior authorization forms for most drug plans o Covermymeds.com REMINDERS TO TAKE MEDICATION: • Medication reminder by Email, Phone call, or Text message o Sugaredspoon.com ANSWER MOST QUESTIONS ABOUT MEDICATIONS: • Univ. of Michigan/West Virginia Schools of Pharmacy o Justaskblue.com • Interactions between medications, over-the-counter (OTC) products and some foods; also has a pictorial Pill Identifier: May input an entire list of medications o Drugs.com OTHER TRUSTED SITES: • Patient friendly information about disease and diagnoses o Mayoclinic.com, familydoctor.org • Package inserts, boxed warnings, “Dear Doctor” letters (can sign up to receive e- mail alerts) o Dailymed.nlm.nih.gov • Communications about drug safety o www.Fda.gov/cder/drug/drugsafety/drugindex.htm • Purchasing medications on-line o Pharnacychecker.com Updated 2013 Psychotropic Medication for Persons with Developmental Disabilities April 23, 2013 Richard Berchou, Pharm. D. Assoc. Clinical Prof., Dept. Psychiatry & Behavioral -

CHAPTER 6 Sleep and Stroke G.J

CHAPTER 6 Sleep and Stroke G.J. Meskill*, C. Guilleminault** *Comprehensive Sleep Medicine Associates, Houston, TX, USA **The Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine, Redwood City, CA, USA OUTLINE Introduction 115 Stroke, Parasomnias, and Sleep- Related Movement Disorders 120 Sleep Apnea is a Risk Factor for Stroke 115 Diagnosis 120 Pathophysiology 116 Treatment 122 Stroke Increases the Risk of Sleep Apnea 118 Conclusions 123 Stroke and the Sleep–Wake Cycle 118 References 124 INTRODUCTION Stroke, defined as a focal neurological deficit of acute onset and vascular origin, is the sec- ond leading cause of death worldwide and is a major source of physical, psychological, and monetary hardship. There are more than 15 million cases worldwide annually, and 795,000 in the United States alone. In total, 137,000 stroke patients will die from stroke complications, and more than 50% will have physical and mental impairment.1 Factoring healthcare services, medications, and productivity loss, strokes cost the United States $34 billion annually.2 SLEEP APNEA IS A RISK FACTOR FOR STROKE Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by recurrent episodes of partial or complete interruption in breathing during sleep due to increased upper airway resistance. OSA has been identified as an independent risk factor for several cardiovascular and cerebrovascular Sleep and Neurologic Disease. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804074-4.00006-6 Copyright © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 115 116 6. SLEEP AND STROKE morbidities, including hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.3–6 The incidence of OSA varies due to significant differ- ences in the sensitivity of testing sites, testing modalities (e.g., in-laboratory polysomnog- raphy vs. -

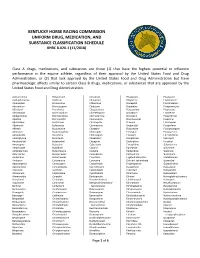

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias Second Edition WORK GROUP ON ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE AND OTHER DEMENTIAS Peter V. Rabins, M.D., M.P.H., Chair Deborah Blacker, M.D., Sc.D. Barry W. Rovner, M.D. Teresa Rummans, M.D. Lon S. Schneider, M.D. Pierre N. Tariot, M.D. David M. Blass, M.D., Consultant STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Barbara Schneidman, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. Woods, M.D., Ph.D. AREA AND COMPONENT LIAISONS Joseph Berger, M.D. (Area I) C. Deborah Cross, M.D. (Area II) Harry A. Brandt, M.D. (Area III) Philip M. Margolis, M.D. (Area IV) John P. D. Shemo, M.D. (Area V) Barton J. Blinder, M.D. (Area VI) David L. Duncan, M.D. (Area VII) Mary Ann Barnovitz, M.D. Anthony J. Carino, M.D. Zachary Z. Freyberg, M.D., Ph.D. Sheila Hafter Gray, M.D. Tina Tonnu, M.D. Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. -

Sundowning Behavior and Nonpharmacological Intervention Migmar Wangchuk

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Nursing Capstones Department of Nursing 2-4-2018 Sundowning Behavior and Nonpharmacological Intervention Migmar Wangchuk Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones Recommended Citation Wangchuk, Migmar, "Sundowning Behavior and Nonpharmacological Intervention" (2018). Nursing Capstones. 276. https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones/276 This Independent Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Nursing at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nursing Capstones by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTION FOR SUNDONWING 1 Sundowning Behavior and Nonpharmacological Intervention Migmar Wangchuk Master of Science in Nursing, University of North Dakota, 2018 An Independent Study Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota January 2018 NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTION FOR SUNDOWNING BEHAVIOR 2 Abstract Dementia patients commonly experience sundowning behavior which includes the following symptoms: restlessness, agitation, aggression, anxiety, swearing and confusion (NIH, 2013). Bachman and Rabins (2005) claim that in the U.S., 13% of dementia patients who experience sundowning behavior live in nursing homes and 66% live in community dwellings. Disruptive behaviors can burden caregivers and eventually institutionalize clients. The etiology of sundowning behaviors is unknown and there may be multiple factors such as, unmet physiological, emotional and psychological needs (NIH, 2013). American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines (2014) for the treatment of dementia recommend the use of psychosocial interventions to improve and maintain cognition, mood, behavior and quality of life. -

Textbook of Disaster Psychiatry

Textbook of Disaster Psychiatry Edited by Robert J. Ursano Carol S. Fullerton Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Lars Weisaeth University of Oslo Beverley Raphael University of Western Sydney CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS I Assessment and management of medical-surgical disaster· casualties James R. Rundell Introduction identify how postdisaster patient triage and manage ment can incorporate behavioral/psychiatric assess Having medical or surgical injuries or conditions ment and treatment, merging behavioral and following a disaster or terrorist attack increases the medical approaches in the differential diagnosis likelihood a psychiatric condition is also present. and early management of common psychiatric syn Fear of exposure to toxic agents can drive many dromes among medical-surgical disaster or terrorism times more patients to medical facilities than actual casualties. terrorism-related toxic exposures. Existing post disaster and post-terrorism algorithms consider pre dominantly medical and surgical triage and patient Phases of individual and community management. There are few specific empirical data responses to terrorism and disasters: about the potential effectiveness of neuropsychiatric integrating psychiatric management triage and treatment integrated into the medical into disaster victim medical-surgical surgical triage and management processes (Burkle, triage and treatment 1991). This is unfortunate, since there are lines of evidence to suggest that early identification of Disasters include natural disasters as well as human psychiatric casualties can help decrease medical made disasters such as terrorist attacks with explo surgical treatment burden, decrease inappropriate sives, chemicals, and biological agents. In cases of treatments of patients, and possibly decrease long disaster or terrorism, particularly when the scope of term psychological sequelae in some patients potential casualties could overwhelm local response (Rundell, 2000). -

Impact of Parity

Appendix D. List of Medications for Identifying MH/SA Use and Spending Restricted and expanded Restricted and expanded Major Depressive MH/SA medications Disorder medications 1 = Restricted 1 = Restricted Drug generic name Drug brand name 0 = Expanded* 0 = Expanded** Donepezel Aricept 1 0 Galantamine Reminyl 1 0 Tacrine Cognex 1 0 Rivastigmine Exelon 1 0 Amitriptyline Elavil, Endep, Amitid 1 1 Clomipramine Anafranil 1 1 Desipramine Norpramin, Pertofrane 1 1 Doxepin Sinequan, Zonalon 1 1 Imipramine Tipramine, Tofranil, Tofranil-PM, 1 1 Norfranil Nortriptyline Aventyl, Pamelor 1 1 Protriptyline Vivactil 1 1 Trimipramine Surmontil 1 1 Amoxapine Asendin 1 1 Maprotiline Ludiomil 1 1 Isocarboxazid Marplan 1 1 Meclobemide Aurorix 1 1 Phenelzine Nardil 1 1 Tranylcypromine Parnate 1 1 Citalopram Celexa 1 1 Escitalopram Lexapro 1 1 Fluoxetine Prozac, Sarafem, Prozac Weekly 1 1 Fluvoxamine Luvox 1 1 Paroxetine Paxil 1 1 Sertraline Zoloft 1 1 Bupropion Wellbutrin, Wellbutrin SR 1 1 Mirtazapine Remeron, Remeron SolTab 1 1 Nefazodone Serzone 1 1 Reboxetine Vestra, Edronax 1 1 Venlafaxine Effexor, Effexor XR 1 1 Trazodone Desyrel, Trazolan, Trialodine, 1 1 Dotazone Chlordiazepoxide/amitriptyline Limbitrol, Limbitrol-DS 1 1 Perphenazine/amitriptyline Etrafon, Etrafon-A, Etrafon-Forte, 1 1 Triavil Carbamazepine Atretol, Epitol, Tegretol, Tregetol- 0 0 Evaluation of Parity in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program D-1 Restricted and expanded Restricted and expanded Major Depressive MH/SA medications Disorder medications 1 = Restricted 1 = Restricted -

Special Project

National Mental Health Benchmarking Project Forensic Forum Special Project Seclusion Medication Audit A joint Australian, State and Territory Government Initiative October 2007 National Benchmarking Project - Forensic Forum Seclusion Medication Audit In previous benchmarking work conducted by the National Benchmarking Project – Forensic Forum on reviewing the Australian Council of Health Care Standards (ACHS) seclusion indicators, significant variation in organisational performance was noted. Participants agreed to further explore, in detail, seclusion events. A detailed audit of seclusion was conducted by participating services in late 2006. Discussion of possible reasons for variation identified that there may be differing prescribing patterns of psychotropic medication. The aim of this sub-project was to better understand the reasons for variation in seclusion practices and prescribing patterns across participating organizations Method: Consumer level data to be submitted for each consumer who was an inpatient on 1st November 2005 for acute in-scope services. Same day admissions are not included in this collection. Detailed specifications for this project were developed by the Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit (QMHBU) with advice and endorsement from the National Benchmarking Project Forensic Forum. Formulae for calculation of Chlorpromazine and Benzodiazepine (Valium) equivalent doses are included in the specifications. This report was compiled by the QMHBU on behalf of the National Benchmarking Project – Forensic Forum; it includes the findings of this sub-project. Service Profile A B C D Group Total number of consumers in census 44 43 40 28 155 Average number of days for consumers (Nov) 25 12 27 29 22 Data was collected for 155 consumers. Average length of stay during the month of data collection was the lowest for Org B (12 days), but was similar for the other participating services (25-29 days). -

Electronic Search Strategies

Appendix 1: electronic search strategies The following search strategy will be applied in PubMed: ("Antipsychotic Agents"[Mesh] OR acepromazine OR acetophenazine OR amisulpride OR aripiprazole OR asenapine OR benperidol OR bromperidol OR butaperazine OR Chlorpromazine OR chlorproethazine OR chlorprothixene OR clopenthixol OR clotiapine OR clozapine OR cyamemazine OR dixyrazine OR droperidol OR fluanisone OR flupentixol OR fluphenazine OR fluspirilene OR haloperidol OR iloperidone OR levomepromazine OR levosulpiride OR loxapine OR lurasidone OR melperone OR mesoridazine OR molindone OR moperone OR mosapramine OR olanzapine OR oxypertine OR paliperidone OR penfluridol OR perazine OR periciazine OR perphenazine OR pimozide OR pipamperone OR pipotiazine OR prochlorperazine OR promazine OR prothipendyl OR quetiapine OR remoxipride OR risperidone OR sertindole OR sulpiride OR sultopride OR tiapride OR thiopropazate OR thioproperazine OR thioridazine OR tiotixene OR trifluoperazine OR trifluperidol OR triflupromazine OR veralipride OR ziprasidone OR zotepine OR zuclopenthixol ) AND ("Randomized Controlled Trial"[ptyp] OR "Controlled Clinical Trial"[ptyp] OR "Multicenter Study"[ptyp] OR "randomized"[tiab] OR "randomised"[tiab] OR "placebo"[tiab] OR "randomly"[tiab] OR "trial"[tiab] OR controlled[ti] OR randomized controlled trials[mh] OR random allocation[mh] OR double-blind method[mh] OR single-blind method[mh] OR "Clinical Trial"[Ptyp] OR "Clinical Trials as Topic"[Mesh]) AND (((Schizo*[tiab] OR Psychosis[tiab] OR psychoses[tiab] OR psychotic[tiab] OR disturbed[tiab] OR paranoid[tiab] OR paranoia[tiab]) AND ((Child*[ti] OR Paediatric[ti] OR Pediatric[ti] OR Juvenile[ti] OR Youth[ti] OR Young[ti] OR Adolesc*[ti] OR Teenage*[ti] OR early*[ti] OR kids[ti] OR infant*[ti] OR toddler*[ti] OR boys[ti] OR girls[ti] OR "Child"[Mesh]) OR "Infant"[Mesh])) OR ("Schizophrenia, Childhood"[Mesh])).