A Journal of Christian Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESBYTERIANISM in AMERICA the 20 Century

WRS Journal 13:2 (August 2006) 26-43 PRESBYTERIANISM IN AMERICA The 20th Century John A. Battle The final third century of Presbyterianism in America has witnessed the collapse of the mainline Presbyterian churches into liberalism and decline, the emergence of a number of smaller, conservative denominations and agencies, and a renewed interest in Reformed theology throughout the evangelical world. The history of Presbyterianism in the twentieth century is very complex, with certain themes running through the entire century along with new and radical developments. Looking back over the last hundred years from a biblical perspective, one can see three major periods, characterized by different stages of development or decline. The entire period begins with the Presbyterian Church being overwhelmingly conservative, and united theologically, and ends with the same church being largely liberal and fragmented, with several conservative defections. I have chosen two dates during the century as marking these watershed changes in the Presbyterian Church: (1) the issuing of the 1934 mandate requiring J. Gresham Machen and others to support the church’s official Board of Foreign Missions, and (2) the adoption of the Confession of 1967. The Presbyterian Church moves to a new gospel (1900-1934) At the beginning of the century When the twentieth century opened, the Presbyterians in America were largely contained in the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. (PCUSA, the Northern church) and the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (PCUS, the Southern church). There were a few smaller Presbyterian denominations, such as the pro-Arminian Cumberland Presbyterian Church and several Scottish Presbyterian bodies, including the United Presbyterian Church of North America and various other branches of the older Associate and Reformed Presbyteries and Synods. -

Commissioned Orchestral Version of Jonathan Dove’S Mansfield Park, Commemorating the 200Th Anniversary of the Death of Jane Austen

The Grange Festival announces the world premiere of a specially- commissioned orchestral version of Jonathan Dove’s Mansfield Park, commemorating the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen Saturday 16 and Sunday 17 September 2017 The Grange Festival’s Artistic Director Michael Chance is delighted to announce the world premiere staging of a new orchestral version of Mansfield Park, the critically-acclaimed chamber opera by composer Jonathan Dove and librettist Alasdair Middleton, in September 2017. This production of Mansfield Park puts down a firm marker for The Grange Festival’s desire to extend its work outside the festival season. The Grange Festival’s inaugural summer season, 7 June-9 July 2017, includes brand new productions of Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, Bizet’s Carmen, Britten’s Albert Herring, as well as a performance of Verdi’s Requiem and an evening devoted to the music of Rodgers & Hammerstein and Rodgers & Hart with the John Wilson Orchestra. Mansfield Park, in September, is a welcome addition to the year, and the first world premiere of specially-commissioned work to take place at The Grange. This newly-orchestrated version of Mansfield Park was commissioned from Jonathan Dove by The Grange Festival to celebrate the serendipity of two significant milestones for Hampshire occurring in 2017: the 200th anniversary of the death of Austen, and the inaugural season of The Grange Festival in the heart of the county with what promises to be a highly entertaining musical staging of one of her best-loved novels. Mansfield Park was originally written by Jonathan Dove to a libretto by Alasdair Middleton based on the novel by Jane Austen for a cast of ten singers with four hands at a single piano. -

Bishop) Emailed (4) Charleston-Epis-Pod and Goodllate 2/2/19

Episcopal Church in South Carolina (Charleston, SC)—Gladstone Adams (Bishop) emailed (4) Charleston-Epis-Pod and Goodllate 2/2/19 Faith International University & Seminary (Tacoma, WA)—Michael Adams (President) faxed and emailed Tacoma and Goodlatte 2/16/19 Northeastern Ohio Synod (Cuyahoga Falls, OH) —Abraham Allende (Bishop) faxed and emailed (4) Cuyahoga Falls and Goodlatte 2/4/19 Geneva Reformed Seminary (Greenville, SC) —Mark Allison (President) emailed Greenville-Orth-Pod and Goodlatte 2/17/19 Nashotah House (Nashotah, WI) — Garwood Anderson (President) faxed and emailed (4) Nashotah and Goodlatte 2/13/19 Episcopal Diocese of California (San Francisco, CA) —Marc Andrus (Bishop) emailed (3) San Francisco-Epis-Pod and Goodlatte 2/2/19 La Crosse Area Synod (La Crosse, WI) —Jim Arends (Bishop) emailed (4) La Crosse-ELCA-Pod and Goodlatte 2/4/19 Chesapeake Bible College & Seminary (Ridgeley, MD) — Carolyn Aronson (Dean) emailed (2) Ridgeley-Orth-Pod and Goodlatte 2/17/19 Benedict College (Columbia, SC) — Roslyn Artis (President) faxed Columbia-Bapt and Goodlatte 2/9/19 North Park Theological Seminary (Chicago, IL) —Debra Auger (Dean) emailed (3) Chicago-Non-Pod and Goodlatte 2/14/19 Howard Payne University (Brownwood, TX) —Donnie Auvenshine (Dean) faxed and emailed (4) Brownwood-Pod and Goodlatte 2/9/19 Archdiocese of New Orleans (New Orleans, LA) —Gregory Aymond (Archbishop) emailed and faxed Goodlatte and New Orelans 2/1/19 Diocese of Birmingham (Birmingham, AL) —Robert Baker (Bishop) emailed (3) and faxed Goodlatte and Birmingham1/31/19 -

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

The Surprising Consistency of Fanny Price

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2019 "I Was Quiet, But I Was Not Blind": The urS prising Consistency of Fanny Price Blake Elizabeth Bowens Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Bowens, Blake Elizabeth, ""I Was Quiet, But I Was Not Blind": The urS prising Consistency of Fanny Price" (2019). All Theses. 3081. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3081 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I WAS QUIET, BUT I WAS NOT BLIND”: THE SURPRISING CONSISTENCY OF FANNY PRICE ——————————————————————————————————— A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University ——————————————————————————————————— In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts English ——————————————————————————————————— by Blake Elizabeth Bowens May 2019 ——————————————————————————————————— Accepted by: Dr. Erin Goss, Committee Chair Dr. Kim Manganelli Dr. David Coombs ABSTRACT Mansfield Park’s Fanny is not the heroine most readers expect to encounter in a Jane Austen novel. Unlike the heroines of Pride and Prejudice, or Emma, for example, she does not have to undergo any period of being wrong, and she does not have to change in order for her position to be accepted. In the midst of conversations about Fanny as a model of perfect conduct book activity, exemplary Christian morals, or Regency era femininity, readers and scholars often focus on whether or not Fanny exists as a perfect and consistent heroine, providing very strong and polarizing opinions on either side. -

“Fanny's Price” Is a Piece of Fan Fiction About Jane Austen's Mansfield Park. I Ch

Introduction to “Fanny’s Price” “Fanny’s Price” is a piece of fan fiction about Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. I chose to write about Mansfield Park because while it interests me as a scholar, it is very unsatisfying to me as a reader. I was inspired to write this piece primarily by class discussion that led me to think of Fanny as sinister. One day, someone suggested that Fanny refuses to act in the play because she is always acting a part. I immediately thought that if Fanny was only acting righteous and timid, her real personality must be the opposite. On another day, Dr. Eberle mentioned a critical text accusing Fanny of being emotionally vampiric; immediately I thought of making her an actual vampire. When Frankenstein was brought up later, I realized that Fanny should be a vampire’s servant rather than a fully fledged vampire. She does not understand why Edmund prefers Mary, when he made her what she is. Because the film Mansfield Park makes Fanny essentially Jane Austen, it gives her power over all of the other characters and the plot. Watching it encouraged me to think of Fanny as manipulative. I find a reading of Fanny as a villain much more satisfying than my former reading of her as completely passive. I wrote “Fanny’s Price” in an alternate universe because that was the only way I could include real rather than metaphorical vampires. I wanted the vampires to be real because I feel that it raises the stakes for Mary, my heroine. I made Mary Crawford the heroine because of class discussion comparing her to Elizabeth Bennett. -

CS 2015.Indd

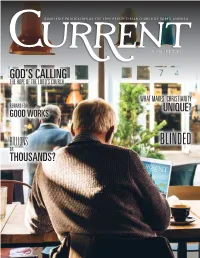

VOL. 4/No. 1 WINTER 2015 GOD’S CALLING THE HOPE OF THE LORD’S CHURCH WHAT MAKES CHRISTIANITY REWARD FOR UNIQUE? GOOD WORKS BILLIONS BLINDED OR THOUSANDS? 8 6 9 10 14 18 CONTENTS Subscriptions 3 God’s Calling: The Hope of the Lord’s Church Current is published quarterly by the Free Presbyterian Church of North America (www. 4 In Their Own Words: Rev. Anthony D’Addurno fpcna.org). The annual subscription price is $15.00 (US/CAN). To subscribe, please go to 6 Seminary Report www.fpcna.org/subscriptions. You may also subscribe by writing to Rev. Derrick Bowman, 8 Reward for Good Works 4540 Oakwood Circle, Winston-Salem, NC 27106. Checks should be made payable to Current. Billions or Thousands? 9 General Editor, Rev. Ian Goligher. Assistant Editor, Rev. Andy Foster. Copy Editor, Judy Brown. 10 Presbytery News Graphic Design, Moorehead Creative Designs. Printer, GotPrint.com. ©2015 Free Presbyterian 12 Mission Report Church of North America. All rights reserved. 14 What Makes Christianity Unique? The editor may be reached at [email protected], Church News phone: 604-897-2040, or 16 Cloverdale FPC, 18790 58 Ave., Surrey, BC V3S 9A2. 18 Blinded YOU MAY NOW READ Please consider CURRENT forwarding a link to ONLINE promote the magazine at www.fpcna.org. When at among your contacts the church website click the and friends. Current icon and choose You can still subscribe for a the format for your device. hard copy of each issue and churches may still order copies in bulk to introduce people to the magazine. -

Fanny's Heart Desire Described in Jane Austen's

FANNY’S HEART DESIRE DESCRIBED IN JANE AUSTEN’S MANSFIELD PARK THESIS Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the completion of Strata I Program of the English Language Department Specialized in Literature By: RIRIN HANDAYANI C11.2007.00841 FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LETTERS DIAN NUSWANTORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2012 1 PAGE OF APPROVAL This thesis has been approved by Board of Examiners, Strata 1 Study Program of English Department, Faculty of Languages and Letters, Dian Nuswantoro University on February 21st 2012. Board of Examiners Chairperson The 1st Examiner Haryati Sulistyorini, S.S., M.Hum. R. Asmarani S.S., M.Hum. The 2nd Examiner as 2nd Adviser The 3rd Examiner Sarif Syamsu Rizal, S.S., M.Hum. Valentina Widya, S.S., M.Hum. Approved by Dean of Faculty of Languages and Letters Achmad Basari, S.S., M.Pd. 2 MOTTO I hope you live a life you’re proud of, but if you find that you’re not. I hope you have strength to start all over again. Benjamin Button All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason. Immanuel Kant Imagination is stronger than knowledge; myth is more potent than history, dreams are more powerful than facts, hope always triumphs over experience, laughter is the cure for grief, love is stronger than death. Robert Fulghum 3 DEDICATION To : - My beloved parents and siblings - Rinchun 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At this happiest moment, I wish a prayer to the almighty who has blessed me during the writing of this paper. I would like, furthermore, to express my sincere thanks to: 1. -

2020 Maine SAT School Day Student Answer Sheet Instructions

2020 MAINE SAT® SCHOOL DAY Student Answer Sheet Instructions This guide will help you fill out your SAT® School Day answer you need to provide this information so that we can mail sheet—including where to send your four free score reports. you a copy of your score report.) College Board may Be sure to record your answers to the questions on the contact you regarding this test, and your address will answer sheet. Answers that are marked in this booklet will be added to your record. If you also opt in to Student not be counted. Search Service (Field 16), your address will be shared with If your school has placed a personalized label on your eligible colleges, universities, scholarships, and other answer sheet, some of your information may have already educational programs. been provided. You may not need to answer every question. If you live on a U.S. military base, in Field 10, fill in your box Your instructor will read aloud and direct you to fill out the number or other designation. Next, in Field 11, fill in the appropriate questions. letters “APO” or “FPO.” In Field 12, find the “U.S. Military Confidentiality Bases/Territories” section, and fill in the bubble for the two- letter code posted for you. In Field 13, fill in your zip code. Your high school, school district, and state may receive your Otherwise, for Field 10, fill in your street address: responses to some of the questions. Institutions that receive Include your apartment number if you have one. your SAT information are required to keep it confidential and to Indicate a space in your address by leaving a blank follow College Board guidelines for using information. -

“A Creditable Establishment”: the Irony of Economics in Jane Austen’S Mansfield Park

“A Creditable Establishment”: The Irony of Economics in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park by Kandice Sharren Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English Kandice Sharren, 2011 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee “A Creditable Establishment”: The Irony of Economics in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park by Kandice Sharren Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Robert Miles, Department of English Supervisor Dr. Gordon Fulton, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Andrea McKenzie, Department of History Outside Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Robert Miles, Department of English Supervisor Dr. Gordon Fulton, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Andrea McKenzie, Department of History Outside Member This thesis contextualises Austen’s novel within the issues of political economy contemporary to its publication, especially those associated with an emerging credit economy. It argues that the problem of determining the value of character is a central one and the source of much of the novel’s irony: the novel sets the narrator’s model of value against the models through which the various other characters understand value. Through language that represents character as the currency and as a commodity in a credit economy, Mansfield Park engages with the problems of value raised by an economy in flux. Austen uses this slipperiness of language to represent social interactions as a series of intricate economic transactions, revealing the irony of social exchanges and the expectations they engender, both within and without the context of courtship. -

Mansfield Park Character Descriptions

MANSFIELD PARK CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS WOMEN’S ROLES Fanny Price: (able to play Young Adult) Full of spirit. Her circumstances force her to “be good," but she has strong opinions and a big imagination. She may come off as shy, but she’s smart and wants to learn everything. She has a strong moral compass which keeps her out of trouble and makes her trustworthy to others. Hopelessly in love with Edmund Bertram. Mary Crawford: (able to play Young Adult) Mary is witty and capable of being hollow and flippant, but not fundamentally bad natured. She is ambitious and clear eyed about the truths of the world and society. She guards her heart, but is a bit of a flirt who intends to marry well. (Sister to Henry Crawford, no blood connection to Fanny Price). Maria Bertram: (able to play Young Adult) Maria is an elegant, mannered, accomplished and fashionable young woman who knows she has to marry Mr. Rushford- but later falls hard for Henry. (Sister to Tom and Edmund, Fanny’s cousin) Mrs. Norris/Mrs. Price: (DOUBLES- able to play 40-65) MRS. NORRIS is bossy and condescending with those who have no power; she feels as if she's in charge of the world. She sucks up to anyone of higher status than herself. A somewhat vicious, indomitable battleship of a woman. MRS. PRICE is a working class woman from Portsmouth. She’s fundamentally forward-looking, but a lifetime of disappointments have worn her down. She’s developed a certain brusque, vaguely-cheerful emotional-remove to deal with it all. -

In Defense of Patricia Rozema's Mansfield Park

In Defense of Patricia t Rozema’s Mansfield Park :Li DAVID MONAGHAN David Monaghan is Professor of English at Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is the author of Jane Austen: Structure and Social Vision and editor of two books of essays on Austen. His other books deal with John le Carré and the literature of the Falklands War. MANSFIELD PARK is the most controversial of all Jane Austen’s novels, mainly because readers are unable to agree in their assessment of the novel’s heroine, Fanny Price. In adapting the novel to the screen, Patricia Rozema adopts two positions that plunge her into the midst of this debate. First, as Alison Shea points out in the essay to which I am responding, she creates a heroine intended to correct the supposed inadequacies of Austen’s original, whom she judges to be “annoying,” “not fully drawn,” and “too slight and retiring and internal” (Herlevi). Second, she proposes that Mansfield Park is a novel about slavery, lesbianism, and incest. Not surprisingly, then, her film version of Mansfield Park has generated more heated discussion than any other adaptation of an Austen novel. At one extreme, Claudia Johnson describes the film as “an audacious and perceptive cinematic evocation of Jane Austen’s distinctively sharp yet forgiving vision” (10), while at the other John Wiltshire argues that “what the film represents is the marketing of a new ‘Jane Austen’ to a post-feminist audience now receptive to its reinvention of the novel” (135). It would be very difficult, in my view, to defend Rozema’s rather eccen- tric interpretation of Mansfield Park against the extremely effective critique offered by Ms.