Arxiv:2001.00954V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 11 Jun 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Possible Planetary Atmospheres in the TRAPPIST-1 System

Space Sci Rev (2020) 216:100 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00719-1 A Review of Possible Planetary Atmospheres in the TRAPPIST-1 System Martin Turbet1 · Emeline Bolmont1 · Vincent Bourrier1 · Brice-Olivier Demory2 · Jérémy Leconte3 · James Owen4 · Eric T. Wolf5 Received: 14 January 2020 / Accepted: 4 July 2020 / Published online: 23 July 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract TRAPPIST-1 is a fantastic nearby (∼39.14 light years) planetary system made of at least seven transiting terrestrial-size, terrestrial-mass planets all receiving a moderate amount of irradiation. To date, this is the most observationally favourable system of po- tentially habitable planets known to exist. Since the announcement of the discovery of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system in 2016, a growing number of techniques and approaches have been used and proposed to characterize its true nature. Here we have compiled a state- of-the-art overview of all the observational and theoretical constraints that have been ob- tained so far using these techniques and approaches. The goal is to get a better understanding of whether or not TRAPPIST-1 planets can have atmospheres, and if so, what they are made of. For this, we surveyed the literature on TRAPPIST-1 about topics as broad as irradiation environment, planet formation and migration, orbital stability, effects of tides and Transit Timing Variations, transit observations, stellar contamination, density measurements, and numerical climate and escape models. Each of these topics adds a brick to our understand- ing of the likely—or on the contrary unlikely—atmospheres of the seven known planets of the system. -

The Space Environment and Atmospheric Joule Heating of the Habitable Zone Exoplanet TOI 700 D

The Astrophysical Journal, 897:101 (11pp), 2020 July 1 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab9637 © 2020. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. The Space Environment and Atmospheric Joule Heating of the Habitable Zone Exoplanet TOI 700 d Ofer Cohen1 , C. Garraffo2,3 ,Sofia-Paraskevi Moschou3 , Jeremy J. Drake3 , J. D. Alvarado-Gómez4 , Alex Glocer5, and Federico Fraschetti6 1 Lowell Center for Space Science and Technology, University of Massachusetts Lowell, 600 Suffolk Street, Lowell, MA 01854, USA; [email protected] 2 Institute for Applied Computational Science, Harvard University, 33 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA, USA 3 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA, USA 4 Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam, An der Sternwarte 16, D-14482 Potsdam, Germany 5 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA 6 Dept. of Planetary Sciences-Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Received 2020 February 22; revised 2020 May 5; accepted 2020 May 23; published 2020 July 7 Abstract We investigate the space environment conditions near the Earth-size planet TOI700d using a set of numerical models for the stellar corona and wind, the planetary magnetosphere, and the planetary ionosphere. We drive our simulations using a scaled-down stellar input and a scaled-up solar input in order to obtain two independent solutions. We find that for the particular parameters used in our study, the stellar wind conditions near the planet are not very extreme—slightly stronger than that near the Earth in terms of the stellar wind ram pressure and the intensity of the interplanetary magnetic field. -

Open Engagment Group A

Habitable Worlds 2021 Workshop Open Engagement – Group B Abstract Title 1st Author # 19 Obliquity Variation of Circumbinary Planets Gongjie Li Removing Stellar Activity Signals from Radial 34 Zoe de Beurs Velocity Measurements Using Neural Networks 40 Dayside land on tidally locked M-Earths Evelyn Macdonald Effect of mantle oxidation state on the magma ocean 87 Nisha Katyal atmospheric evolution Stellar Variability & Precision Radial Velocimetry: 89 Eric Ford Lessons for atmospheric characterization Is there any other habitable planets in universe 91 Md Redyan Ahmed except Earth? Stellar Energetic Particle-driven Production of Biologically Relevant Molecules in Atmospheres of 93 Guillaume Gronoff Young Earth-like Exoplanets Around Active G-K Stars 97 Stable, Closely-Spaced Three-Planet Systems Sacha Gavino Ground-Based Exoplanet Direct Imaging in the Next 98 Thayne Currie Decade: The Path to Imaging Another Earth Magma ocean differentiation regime in the earliest 101 Damanveer Grewal formed rocky bodies -Internal or External? A very early origin of isotopically distinct nitrogen 102 Damanveer Grewal in the inner Solar System protoplanets XUV-Driven Atmospheric Mass Loss of M Dwarf 103 Laura Amaral Planets due to Flaring Impact of Tides on the Potential for Exoplanets to 104 Armen Tokadjian Host Exomoons 105 Drifting into habitability Bradley Hansen 106 How to Detect a Dead Planet Sara Walker Computational study on the importance of UV light 107 in the production of molecules of prebiotic Marion Armas Vazquez importance in an astrobiological -

Canopus XVII Básicamente La Escribió Él

N° 17 ENE 2020 rreevviissttaa ccaannooppuuss LA REVISTA DE COMUNICACIÓN CIENTÍFICA EDITORIAL Empezamos un nuevo año, 2020, siempre que cambia ese número, el común de las personas siente una renovación, nuevos objetivos, nuevo “aire” como comúnmente se dice. Por nuestra parte, en este enero 2020 estamos mucho mejor parados que en enero del año pasado, de hecho hace un año no hubo publicaciones, comenzamos en febrero con el número V cuando asumí la dirección editorial de este medio digital. Vale destacar algo que no mencionamos en el número pasado, hubo cambio de gestión y organigrama. El Complejo Planetario Malargüe no es más una dirección, si no que es una coordinación. Dicha coordinación, de Marcelo Salvadores depende de la dirección de Industrias y Negocios municipales, a cargo de Marilé Verón. Subiendo un escalón más está la Secretaría Rural, Tecnología Ciencia e Innovación bajo el mando de nuestro ex compañero, César Ojeda, a quien felicitamos desde nuestro pequeño espacio conformado por Agustín y yo. Como hemos ido haciendo estos últimos meses, se ha incrementado la cantidad de contenido, lo que nos lleva a agregar más páginas, digitales por suerte a esta revista. Este número supera las 70 páginas y hablamos de temáticas muy variadas. Quiero agradecer a Agustín, ya que desde el 10 de diciembre soy Coordinador Científico del Planetario, y, por temas de temporada y arreglos, el estar ocupado en esos temas, no he podido dedicarme a la escritura. Canopus XVII básicamente la escribió él. Comenzamos el año con la noticia de que ¡Argentina tiene un planeta! No es tan literal, pero sí que pudimos nombrar a uno, el concurso fue desde la UAI y canalizado desde el Nodo Nacional Argentino para la difusión de la Astronomía, donde el Planetario fue parte. -

The Tessmann Planetarium Guide to Exoplanets

The Tessmann Planetarium Guide to Exoplanets REVISED SPRING 2020 That is the big question we all have: Are we alone in the universe? Exoplanets confirm the suspicion that planets are not rare. -Neil deGrasse Tyson What is an Exoplanet? WHAT IS AN EXOPLANET? Before 1990, we had not yet discovered any planets outside of our solar system. We did not have the methods to discover these types of planets. But in the three decades since then, we have discovered at least 4158 confirmed planets outside of our system – and the count seems to be increasing almost every day. We call these worlds exoplanets. These worlds have been discovered with the help of new and powerful telescopes, on Earth and in space, including the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The Kepler Spacecraft (artist’s conception, below) and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) were specifically designed to hunt for new planets. Kepler discovered 2662 planets during its search. TESS has discovered 46 planets so far and has found over 1800 planet candidates. In Some Factoids: particular, TESS is looking for smaller, rocky exoplanets of nearby, bright stars. An earth-sized planet, TOI 700d, was discovered by TESS in January 2020. This planet is in its star’s Goldilocks or habitable zone. The planet is about 100 light years away, in the constellation of Dorado. According to NASA, we have discovered 4158 exoplanets in 3081 planetary systems. 696 systems have more than one planet. NASA recognizes another 5220 unconfirmed candidates for exoplanets. In 2020, a student at the University of British Columbia, named Michelle Kunimoto, discovered 17 new exoplanets, one of which is in the habitable zone of a star. -

Andrew Vanderburg 77 Massachusetts Avenue • Mcnair Building (MIT Building 37) • Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected] •

Andrew Vanderburg 77 Massachusetts Avenue • McNair Building (MIT Building 37) • Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected] • https://avanderburg.github.io Appointments Assistant Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology July 2021 - present Assistant Professor of Astronomy at The University of Wisconsin-Madison August 2020 - August 2021 Research Associate at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory September 2017 - present NASA Sagan Postdoctoral Fellow at The University of Texas at Austin September 2017 - August 2020 Postdoctoral Associate at Harvard University July 2017 - September 2017 Education Harvard University Cambridge, MA Ph.D. Astronomy and Astrophysics (2017) August 2013 - May 2017 A.M. Astronomy and Astrophysics (2015) University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA B.A. Physics and Astrophysics (2013) August 2009 - May 2013 Research Interests • Searching for and studying small planets orbiting other stars • Determining detailed physical properties of terrestrial planets • Learning about the origins and evolution of planetary systems • Testing theories of planetary migration by studying the architecture of planetary systems • Measuring the prevalence of planets in different galactic environments • Developing and using new data analysis techniques in astronomy, including machine learning and deep learning. Awards • 2021 Wisconsin Undergraduate Research Scholars Exceptional Mentorship Award • 2020 Scialog Fellow • 2018 NASA Exceptional Public Achievement Medal • 2017 NASA Sagan Fellow • 2016 Publications of the -

Directed Panspermia Synthetic DNA in Bioforming Planets

Physical Sciences ︱ Roy Sleator & Niall Smith Directed Panspermia Synthetic DNA in bioforming planets As our technological nter-planetary travel. Terraforming. their atmospheric and surface conditions. advancements continue, Synthetic DNA. These all sound like Astrobiology brings these two focuses scientists are beginning to Iplot points from classic science fiction together as researchers look at the origins turn what was science fiction novels, but everyday science is closing the of life on Earth, as well as looking for into reality. Concepts such as gap between concepts that were once evidence of life on other planets. terraforming and travel between reserved for fantasy and research marking stars are becoming more the boundaries of human development. Prof Roy Sleator is a molecular biologist achievable, giving life to the The idea that humanity might one day at the Cork Institute of Technology in dream that one day we might leave Earth and colonise planets across Ireland. He works together with Dr Niall colonise other planets. Directed the galaxy is an inspirational dream that Smith, astrophysicist at Blackrock Castle panspermia is one method of is rapidly becoming a reality, thanks to Observatory, and the researchers are altering a hostile, uninhabited the cutting-edge developments across a particularly interested in planets beyond Chances are slim to find a planet with perfect conditions planet to a more Earth-like to host human life. Therefore, scientists study bioforming: variety of scientific disciplines. our solar system that may support life. As the seeding of a planet with life. environment, and Cork Institute Earth’s population grows and resources of Technology’s Professor Roy One such discipline is astrobiology, which become stretched, scientists are looking Sleator and Dr Niall Smith is the intersection of biology and physics. -

16207 (Stsci Edit Number: 2, Created: Friday, January 8, 2021 at 2:00:24 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview

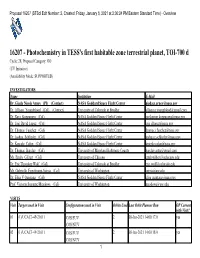

Proposal 16207 (STScI Edit Number: 2, Created: Friday, January 8, 2021 at 2:00:24 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview 16207 - Photochemistry in TESS's first habitable zone terrestrial planet, TOI-700 d Cycle: 28, Proposal Category: GO (UV Initiative) (Availability Mode: SUPPORTED) INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Dr. Giada Nicole Arney (PI) (Contact) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] Dr. Allison Youngblood (CoI) (Contact) University of Colorado at Boulder [email protected] Dr. Ravi Kopparapu (CoI) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] Dr. Eric David Lopez (CoI) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] Dr. Thomas Fauchez (CoI) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] Dr. Joshua Schlieder (CoI) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] Dr. Knicole Colon (CoI) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] Dr. Thomas Barclay (CoI) University of Maryland Baltimore County [email protected] Ms. Emily Gilbert (CoI) University of Chicago [email protected] Dr. Eric Theodore Wolf (CoI) University of Colorado at Boulder [email protected] Ms. Gabrielle Engelmann-Suissa (CoI) University of Washington [email protected] Dr. Elisa V Quintana (CoI) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] Prof. Victoria Suzanne Meadows (CoI) University of Washington [email protected] VISITS Visit Targets used in Visit Configurations used in Visit Orbits Used Last Orbit Planner Run OP Current with Visit? 01 (1) UCAC3-49-21611 -

Fyzikální Chemie Bc. Tereza Kaiserová

Univerzita Karlova Přírodovědecká fakulta Studijní program: Fyzikální chemie Bc. Tereza Kaiserová Phosphine and nitrous oxide as false-positive biosignature gases in planetary spectra Fosfan a oxid dusný jako falešně pozitivní biosignatury ve spektrech planet Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: RNDr. Martin Ferus, Ph.D. Praha, 2021 Charles University Faculty of Science Univerzita Karlova Přírodovědecká fakulta Study programme: Physical chemistry Bc. Tereza Kaiserová Phosphine and nitrous oxide as false-positive biosignature gases in planetary spectra Fosfan a oxid dusný jako falešně pozitivní biosignatury ve spektrech planet Diploma thesis Supervisor: RNDr. Martin Ferus, Ph.D. Prague, 2021 Charles University Faculty of Science Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci zpracovala samostatně a že jsem uvedla všechny použité informační zdroje a literaturu. Tato práce ani její podstatná část nebyla předložena k získání jiného nebo stejného akademického titulu. V Praze, 16. 06. 2021 Bc. Tereza Kaiserová podpis studenta Tato práce byla podpořena projektem GAČR reg. č. 19-03314S, kontraktem ESA reg. č. PEA4000131855 “Manufacturing and testing of mirrors for the ARIEL satellite mission” a projektem MŠMT - ERDF/ESF “Centrum pokročilých aplikovaných věd” reg. č. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16019/0000778. 3 Acknowledgements I would like to use this page to thank all the people who had a positive impact on my life and my work! First of all, I would like to thank my parents for always supporting me, I know you have sacrificed a lot for me to be this happy! I would like to thank my fiancé for always being my rock, for listening to me and for making me happy every time he sees that I need it. -

Venus Versus Earth Analogs

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 14, EPSC2020-1001, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-1001 Europlanet Science Congress 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Atmospheric Escape From TOI-700 d: Venus versus Earth Analogs Chuanfei Dong, Meng Jin, and Manasvi Lingam Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA ([email protected]) The recent discovery of an Earth-sized planet (TOI-700 d) in the habitable zone of an early-type M- dwarf by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite constitutes an important advance. In this Letter, we assess the feasibility of this planet to retain an atmosphere – one of the chief ingredients for surface habitability – over long timescales by employing state-of-the-art magnetohydrodynamic models to simulate the stellar wind and the associated rates of atmospheric escape. We take two major factors into consideration, namely, the planetary atmospheric composition and magnetic field. In all cases, we determine that the atmospheric ion escape rates are potentially a few orders of magnitude higher than the inner Solar system planets, but TOI-700 d is nevertheless capable of retaining a 1 bar atmosphere over gigayear timescales for certain regions of the parameter space. The simulations show that the unmagnetized TOI-700 d with a 1 bar Earth-like atmosphere could be stripped away rather quickly (< 1 gigayear), while the unmagnetized TOI-700 d with a 1 bar CO2-dominated atmosphere could persist for many billions of years; we find that the magnetized Earth-like case falls in between these two scenarios. We also discuss the prospects for detecting radio emission of the planet (thereby constraining its magnetic field) and discerning the presence of an atmosphere. -

2020-01-08 – Live at AAS - Page 1 of 20

NASA’s Universe of Learning - 2020-01-08 – Live at AAS - Page 1 of 20 Dr. Edward Guinan 0:00 [Slide 7] This gives you a distribution, stellar distribution, of stars with spectral type within 10 parsecs, about 33 light years. And we see that M dwarfs dominate with 73% of all stars. K stars are at 44, not 44%, but 13%. And G stars, main sequence G stars are only 4%. So, G stars are rather rare, when it comes to stars in general. Dr. Edward Guinan 0:33 [Slide 8] Next, please. This plays a role. This is a plot of evolution. It's a luminosity of the star in log scale versus stellar age in billions of years. And we see like an F star, a star like 1.4 solar masses, doesn't live very long. A couple billion years. The sun has a longer time to live, up to about 10 billion years. And its luminosity changes, it gets brighter as the nuclear reaction rates increase, about six and a half to 7% per billion years. What I want you to look at is that the Sun changes. We're now in the inner edge of what's called the habitable zone of the Sun. In a half a billion to 2 billion years, we're no longer in the habitable zone. The habitable Zone is where you can have liquid water; we lose that. So, at the bottom there is K stars [which] evolve at 2% increase in luminosity per billion years. And M stars don't change at all. -

Atmospheric Escape from TOI-700 D: Venus Versus Earth Analogs

18th VEXAG Meeting 2020 (LPI Contrib. No. 2356) 8001.pdf Atmospheric Escape From TOI-700 d: Venus versus Earth Analogs. C. Dong1, M. Jin2, M. Lingam3, 1Princeton University ([email protected]), 2Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Lab, 3FIT/Harvard-Cfa Introduction: The recent discovery of an Earth- indicate the orbits of three planets, namely, TOI-700 b, sized planet (TOI-700 d) in the habitable zone of an TOI-700 c, and TOI-700 d. (b) Stellar wind dynamic early-type M-dwarf by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey pressure in the equatorial plane normalized by the solar Satellite constitutes an important advance. Here we as- wind dynamic pressure at 1 AU. (c) Stellar wind density sess the feasibility of this planet to retain an atmosphere in the equatorial plane normalized by the solar wind – one of the chief ingredients for surface habitability – density at 1 AU. In panels (b) and (c), the dashed line over long timescales by employing state-of-the-art mag- represents the critical surface location. netohydrodynamic models to simulate the stellar wind and the associated rates of atmospheric escape. We take two major factors into consideration, namely, the plan- etary atmospheric composition and magnetic field. In all cases, we determine that the atmospheric ion escape rates are potentially a few orders of magnitude higher than the inner solar system planets, but TOI-700 d is nevertheless capable of retaining a 1 bar atmosphere over gigayear timescales for certain regions of the pa- rameter space. The simulations show that the unmagnet- ized TOI-700 d with a 1 bar Earth-like atmosphere could be stripped away rather quickly (<1 gigayear), while the unmagnetized TOI-700 d with a 1 bar CO2-dominated atmosphere could persist for many billions of years; we Figure 2: The logarithmic scale contour plots of the O+ find that the magnetized Earth-like case falls in between −3 these two scenarios.