The Political Theory of the New Deal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stalinist Terror and Democracy: the 1937 Union Campaign

Stalinist Terror and Democracy: The 1937 Union Campaign WENDY GOLDMAN IN A PRISON CAMP IN THE 1930S, a young Soviet woman posed an anguished question in a poem about Stalinist terror: We must give an answer: Who needed The monstrous destruction of the generation That the country, severe and tender. Raised for twenty years in work and battle?^ Historians, united only by a commitment to do this question justice, differ sharply about almost every aspect of "the Great Terror":^ the intent of the state, the targets of repression, the role of external and internal pressures, the degree of centralized control, the number of victims, and the reaction of Soviet citizens. One long- prevailing view holds that the Soviet regime was from its inception a "terror" state. Its authorities, intent solely on maintaining power, sent a steady stream of people to their deaths in camps and prisons. The stream may have widened or narrowed over time, but it never stopped flowing. The Bolsheviks, committed to an antidemocratic ideology and thus predisposed to "terror," crushed civil society in order to wield unlimited power. Terror victimized all strata of a prostrate population.^ 1 would like to thank the American Council of Learned Societies for its support, and William Chase, Anton D'Auria, Donald Filtzer, J. Arch Getty, Lawrence Goldman, Jonathan Harris, Donna Harsch, Aleksei Kilichenkov, Marcus Rediker. Carmine Storella, and the members of the Working Class History Seminar in Pittsburgh for their comments and suggestions. ' Yelena Vladimirova, a Leningrad communist who was sent to the camps in the late 1930s, wrote the poem. -

MISALLIANCE : Know-The-Show Guide

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide Misalliance by George Bernard Shaw Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey Artwork: Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide In This Guide – MISALLIANCE: From the Director ............................................................................................. 2 – About George Bernard Shaw ..................................................................................................... 3 – MISALLIANCE: A Short Synopsis ............................................................................................... 4 – What is a Shavian Play? ............................................................................................................ 5 – Who’s Who in MISALLIANCE? .................................................................................................. 6 – Shaw on — .............................................................................................................................. 7 – Commentary and Criticism ....................................................................................................... 8 – In This Production .................................................................................................................... 9 – Explore Online ...................................................................................................................... 10 – Shaw: Selected -

Stalin's Purge and Its Impact on Russian Families a Pilot Study

25 Stalin's Purge and Its Impact on Russian Families A Pilot Study KATHARINE G. BAKER and JULIA B. GIPPENREITER INTRODUCTION This chapter describes a preliminary research project jointly undertaken during the winter of 1993-1994 by a Russian psychologist and an American social worker. The authors first met during KGB's presentation of Bowen Family Systems Theory (BFST) at Moscow State Uni versity in 1989. During frequent meetings in subsequent years in the United States and Russia, the authors shared their thoughts about the enormous political and societal upheaval occurring in Russia in the 1990s. The wider context of Russian history in the 20th-century and its impact on contemporary events, on the functioning of families over several generations, and on the functioning of individuals living through turbulent times was central to these discussions. How did the prolonged societal nightmare of the 1920s and the 1930s affect the popula tion of the Soviet Union? What was the impact of the demented paranoia of those years of to talitarian repression on innocent citizens who tried to live "normal" lives, raise families, go to work, stay healthy, and live out their lives in peace? What was the emotional legacy of Stalin's Purge of 1937-1939 for the children and grandchildren of its victims? Does it continue to have an impact on the functioning of modern-day Russians who are struggling with new societal disruptions during the post-Communist transition to a free-market democracy? These are the questions that led to the research study presented -

George Bernard Shaw in Context Edited by Brad Kent Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04745-7 - George Bernard Shaw in Context Edited by Brad Kent Frontmatter More information GEORGE BERNARD SHAW IN CONTEXT When Shaw died in 1950, the world lost one of its most well-known authors, a revolutionary who was as renowned for his personality as he was for his humour, humanity, and rebellious thinking. He remains a compelling figure who deserves attention not only for how influential he was in his time but also for how relevant he is to ours. This collection sets Shaw’s life and achievements in context, with forty-two chapters devoted to subjects that interested him and defined his work. Contributors explore a wide range of themes, moving from factors that were formative in Shaw’s life, to the artistic work that made him most famous and the institutions with which he worked, to the political and social issues that consumed much of his attention, and, finally, to his influence and reception. Presenting fresh material and arguments, this collection will point to new direc- tions of research for future scholars. brad kent is Associate Professor of British and Irish Literatures at Université Laval and was Visiting Professor at Trinity College Dublin in 2013–14. His recent publications include a critical edition of Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession (2012), The Selected Essays of Sean O’Faolain (forthcoming), and essays in University of Toronto Quarterly, Modern Drama, ARIEL: A Review of International English Literatures, English Literature in Transition, Irish University Review, and The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Theatre. He is also the programme director of the Shaw Symposium, held annually at the Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Canada. -

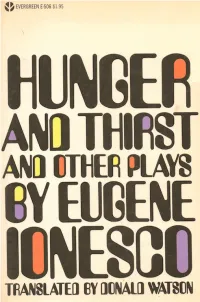

Hunger and Thirst & Other Plays

Hunger and Thirst and Other Plays Other Works by Eugene Ionesco Amedee, The New Tenant, Victims of Duty The Bald Soprano Exit the King Fragments of a journal Four Plays The Killer and Other Plays Notes and Counter Notes Rhinoceros and Other Plays A Stroll in the Air, Frenzy for Two, or More Eugene Ionesco HUNGER AND THIRST and other plays Translated from the French by Donald Watson GI�OVE PI�ESS, II\:C. :'\E\\' YOI�K Theu trar1slatio11S CO/J)' Tighted © 1968 In• Calder all(/ Royars, Ltd. Hrm{!.n a11d Thirst was originally published as La Soif et la Faim ropnigiH ® •!)fiG hl· Editions Galliman!. Paris. The Pic· ttne, Auger, and Salutations were originally publishf'd as Le Tableau, /.a Co/he, Les .\alutatiom copyright © 1!)63 by Edi· tions l.allimarcl, Paris All R ights Resewed l.ibrary of Co11g1·e.u Catalog Card Number: 73-79095 First Printing, 1969 CAl;rJO)';:h T rse plays are full)' protected, in whole, in part or iu any form uuder the copyright laws of thl' United States of America, the Rritis/1 Empire including the Dominion of Can ada, a11d all other countries of the Cop)'right Union, and are sul>ject to royalty. All rights, incl11ding professional, amateur, motion picture, radio, teler>ision, recitation, public rradillfi, and all\' m eth od of photographic reproduction, are strictly resenwl. For /JTOfessiorral rightl all inquiries should l>e addre.Hed to !.rope Prrss, Inc., Ro Unir>ersity Place, New York, X.l'. 1ooo;. For amateur and stock rights all inquiries should be adrlre.«ed to Samuel French, Inc., 25 West 45th Street, Xew York, .V.Y. -

What to Do with Gestus Today Version II

Abstract This thesis explores the common and dialectical features of pedagogy, Bertolt Brecht’s Gestus, and identity construction. It speaks from the perspectives of pedagogue, actor and subject. It argues that in each of these modes the subject is necessarily engaged in both an ontological dilemma and opportunity, which is performative. It exposes embodiment as an oscillatory process of absence and presence. This is predicated on the impossibility of arriving at a fixed notion of being in the world. The thesis is set within an autobiographical frame. First because each mode marks an encounter in the life of Rob Vesty, and second because the practice-based-research uses autobiographical performance. It advances by constructing a piece of performative writing, an autobiographical timeline, to affect an experience of the practice, which informs this thesis. This piece introduces a montage of three juxtaposing studies. The first draws on Rob Vesty’s work in TIE with Splendid Productions and uses the company’s 2007/2008 performance and workshop tour of Brecht’s The Good Woman of Szechuan. It argues that a dialectic, rather than didactic, process must occur in the pedagogic setting and that this is dependent on the presence of a creative gap produced by a strong aesthetic. The second study then argues that the Gestic actor embodies and ‘writes’ this creative gap in a parodic way and that a virtue is made of showing its construction. The final study turns to Rob Vesty’s (2008) solo theatre show – One Man Good Woman – to chart the way identity impacts upon autobiography. It argues that the ‘written’ nature of autobiography and identity renders the subject both absent and present and retains dialectical features in its construction. -

Eugène Ionesco Through the 20Th Century

Cultural and Linguistic Communication HETEROTOPIAS DISTURB: EUGÈNE IONESCO THROUGH THE 20TH CENTURY María Ángeles GRANDE ROSALES1 1. Prof., PhD, Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, Dept. of General Linguistics and Literary Theory, University of Granada, Spain Corresponding author: [email protected] Not only in the theatre, but there also, the 20th Rhinoceros (1959), A Stroll in the Air (1962), Exit century was the century of the disappearance of the King (1962), Hunger and Thirst (1966), Jack, or space and of time transfigured by massacre. The Submission (1970), Macbett (1972), Ce Scientific progress did not produce moral Formidable Bordel (1973), The Man with the Luggage progress. Hiroshima, Auschwitz, Nazism, the (1975), or Journey Among the Dead (1980), also the totalitarianisms, Vietnam present themselves as novel The Hermit (1973), the autobiographical the incontrovertible historical evidence. In the diaries Fragments of a Journal (1967) and Present words of Angelica Liddell: Past, Past Present (1968), and various collections El tiempo ya no ubica las acciones humanas of essays, aesthetic reflections, newspaper sino la descomposición. Un minuto no es articles, marginal notes etc. Born to a Rumanian tiempo, es espacio, espacio desmoronado. father and French mother, he moved to Paris Sería como decir este avión tarda en llegar aged one and lived in France until 1922, when he tres hospitales bombardeados. Sería como was reclaimed by his father and returned to decir un minuto son tres campos de Rumania, where he would continue his exterminio. La definición de sufrimiento secondary and higher education. Later he usurpa la definición del espacio y del tiempo achieved the post of cultural attaché of the (…) La realidad destruida hace que se recurra Rumanian delegation of Vichy, definitively a la metáfora como generadora de realidades establishing himself in France, where he nuevas. -

Certainty, Probability, and Stalin's Great Party Purge

McNair Scholars Journal Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 3 2004 Certainty, Probability, and Stalin’s Great Party Purge Brett omkH es Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Homkes, Brett (2004) C" ertainty, Probability, and Stalin’s Great Party Purge," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol8/iss1/3 Copyright © 2004 by the authors. McNair Scholars Journal is reproduced electronically by ScholarWorks@GVSU. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ mcnair?utm_source=scholarworks.gvsu.edu%2Fmcnair%2Fvol8%2Fiss1%2F3&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages Certainty, Probability, and Stalin’s Great Party Purge ABSTRACT In 1936, Josef Stalin, General Secretary In 1935, Stalin decided to purge his own of the Communist Party of the Soviet party to consolidate power in the Soviet Union [CPSU], initiated a Party Purge, government. Since the inception of historical the extent of which, measured by the research about this event, a debate has numbers of deaths and arrests of Party developed regarding the number of arrests members and their affiliates, has proved and deaths of Soviets ordered by Stalin. This to be highly controversial. A long- study will examine the figures calculated simmering historical debate about this by Western historians to determine where issue surprisingly deepened after the fall correlation and discrepancy exist. The of the Soviet Union brought about the importance of this research is to assess partial opening of government archives the reasons why such dramatic statistical that many thought would answer all differences exist among various historians. -

George Bernard Shaw on the Polish Stage – a Brief Overview

Anna Suwalska-Kołecka Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa w Płocku GEORGE BERNARD Shaw ON THE POLISH stage – A BRIEF overview George Bernard Shaw na polskich scenach – krótki przegląd Abstract The main aim of this paper is to delineate the most crucial aspects of the reception of George Bernard Shaw’s plays in Poland. Shaw, believed to have set the direction of modern British drama, has been welcomed enthusiastically by Polish audiences since the beginning of the twentieth century. Warsaw was called a “Shavian city” and his popularity reached its peak in the years between the two World Wars. After WWII, Shaw’s plays were frequently staged and his political views were presented as being in line with the ruling par- ty’s policies. The fall of Communism brought about a decline in his presence on Polish stag- es, but he reappeared recently in productions that dismantle his plays in postmodern ways. Keywords: Shaw, reception, drama, the twentieth century. Streszczenie Głównym celem tego artykułu jest przedstawienie głównych aspektów recepcji twórczości George’a Bernarda Shaw w Polsce. Uważany za dramatopisarza, który wy- tyczył kierunek rozwoju współczesnego dramatu brytyjskiego, Shaw był witany entu- zjastycznie przez polską widownię od początku dwudziestego wieku. Warszawa nosiła z tego powodu przydomek miasta shawiańskiego, a jego popularność osiągnęła apogeum w okresie międzywojennym. Po wojnie sztuki Shawa były często wystawiane, a lewicowe poglądy autora utożsamiano z obowiązującą linią polityczną partii. Rok 1989 i transforma- cja ustrojowa spowodowała zmniejszenie zainteresowania jego twórczością. Jego sztuki powracają ostatnio na polskie sceny poddane postmodernistycznemu recyclingowi. Słowa kluczowe: Shaw, recepcja, dramat, wiek dwudziesty 1. Introduction George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) is an Irish playwright rated as second only to William Shakespeare in the Anglophone tradition, and the only one who can boast both the Nobel Prize for Literature (1925) and an Academy Award for his screenplay of Pygmalion (1938). -

The Relationship of Shaw's Political Ideas to His Dramatic Art"

G.B.S.: PAMPHLETEER OR PLAYWRIGHT? "The Relationship of Shaw's Political Ideas to His Dramatic Art" By Joyce Long Submitted as an Honors Paper in the Department of English The Woman's College of the University of Uorth Carolina Greensboro, Korth Carolina 1956 Approved hy Examining Committee ^V^> * VfcflJT CGHTEKTS FOREWORD i I. SHAW'S I OLITICAL THOUGHT 1 II. SHAW TIIE PHILOSOPHER 8 III. SHAW TIE COKEC ARTIST 23 IV. SHAW THE ARTIST-PHILOSOPHER 36 FOREWORD Ky purpose in this paper is to answer within the limits of the paper the question, Was Shaw an artist or a propagandist? I propose to arrive at an answer by analyzing what happens to ideas in three of Shaw's plays. Taking his political ideas as a measuring stick, I have selected three plays, Back to Kethuselah, Kan ani Supernan, and Caesar and Cleopatra, which illustrate Shaw'fl treatment of ideas. I have selected these because they treat extensively political ideas and because they were written during the height of Shaw's career as a playwright. Ky chief interest has not been Shaw's political ideasj I have not attempted to explore the ideas in his plays, nor to set forth a political philosophy derived from the plays—I have been interested in what happens to these ideas in the plays, and their relationship to the dramatic fcrm. I have not attempted to trace the development of a dramatic style or technique, nor to explain in terms of Shaw's career why in one play he subordinates idea to art, and in another art to idea. -

J. Arch Getty

J. Arch Getty Afraid of Their Shadows: The Bolshevik Recourse to Terror, 1932-1938 Political terror has long been a basic part of our understanding of the Stalinist sys- tem. First appearing in the earliest days of the Soviet regime, it reached unimagi- nable heights in the 1930s. Historians and political scientists have long speculated on the causes of (or reasons for) the "Great Terror" or "Great Purges" of that dec- ade. Explanations have been extremely varied, ranging from the systemic needs of a "totalitarian" regime to the inherent evils of communism to the megalomaniac needs of an absolutist Stalin. More recently, a variety of other factors have been brought into the academic conversation. Social historians have wondered about social and status conflicts (workers vs. foremen, rank and file party members vs. the party nomenklatura), structural/institutional conflicts (party vs. police, police vs. military), mentalities, and changing social roles in the "quicksand society" of the 1930s1. The opening of central archives of the Communist Party in Moscow offers the opportunity to investigate the high-level political component of the terror phe- nomenon2 .We now have a huge number of memoranda, stenographic records, protocols, and other Central Committee and Politburo documents that can shed a great deal of light on the internal workings of the top-level party leadership. These party documents, most of which were prepared for internal rather than public consumption, can help illustrate the mentality and self-representation of the Bol- shevik leadership, as well as its understanding and construction of reality. The self-image and view of the world of those making key political decisions, includ- ing those relating to terror, would appear to be relevant areas of inquiry. -

George Bernard Shaw – Selected Quotations

GEORGE BERNARD SHAW – SELECTED QUOTATIONS A day's work is a day's work, neither more nor less, and the man who does it needs a day's sustenance, a night's repose and due leisure, whether he be painter or ploughman. A fashion is nothing but an induced epidemic. A fool's brain digests philosophy into folly, science into superstition, and art into pedantry. Hence University education. A life spent making mistakes is not only more honorable, but more useful than a life spent doing nothing. A lifetime of happiness! No man alive could bear it; it would be hell on earth. Americans adore me and will go on adoring me until I say something nice about them. An American has no sense of privacy. He does not know what it means. There is no such thing in the Criminals do not die by the hands of the law. They die by the hands of other men. Democracy is a device that ensures we shall be governed no better than we deserve. England and America are two countries separated by a common language. Everything happens to everybody sooner or later if there is time enough. Few people think more than two or three times a year; I have made an international reputation for myself by thinking once or twice a week. Gambling promises the poor what property performs for the rich--something for nothing. Hegel was right when he said that we learn from history that man can never learn anything from history. Hell is full of musical amateurs.