Frontlines Layout Insides Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cm 9437 – Armed Forces' Pay Review Body – Forty-Sixth Report 2017

Appendix 1 Pay16: Pay structure and mapping1 Trade Supplement Placement (TSP) The Trades within each Supplement are listed alphabetically, and colour coded to represent each Service (dark blue for Naval Service, red for Army, light blue for RAF and purple for the Allied Health Professionals). Supplement 1 Supplement 2 Supplement 3 Aerospace Systems Operating ARMY AAC Groundcrew Sldr Aircraft Engineering (Avionics) and Air Traffic Control including including Aircraft Engineering RAF RAF Air Cartographer Aerospace Systems Operator/Manager, RAF Technician, Aircraft Technician Flight Operations Assistant/Manager RN/RM Comms Inf Sys inc SM & WS (Avionics) and Aircraft Maintenance ARMY Army Welfare Worker ARMY Crewman 2 Mechanic (Avionics) ARMY Custodial NCO AHP Dental Hygienist Air Engineering (Mechanical) including Aircraft Engineering AHP Dental Nurse AHP Dental Technician RAF Technician, Aircraft Technician RN/RM Family Services Aircraft Engineering (Weapon) (Mechanical) and Aircraft Maintenance RAF including Engineering Weapon and (Mechanical) RAF Firefighter Weapon Technician Air Engineering Technician including AHP Health Care Assistant General Engineering including Aircraft Engineering Technician, RN/RM Hydrography & MET (including legacy General Engineering Technician, Aircraft Technician (Avionics) & Aircraft RN/RM NA(MET)) RAF General Technician Electrical, General Maintenance Mechanic (Avionics) Technician (Mechanical) and General RN/RM Logs (Writer) inc SM RN/RM Aircrewman (RM, ASW, CDO) Technician Workshops Logistics (Caterer) -

A Pictorial Record of the Combat Duty of Patrol Bombing Squadron One Hundred Nine in the Western Pacific, 20 April 1945-15 August 1945 Theodore Manning Steele

Bangor Public Library Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl World War Regimental Histories World War Collections 1946 A pictorial record of the combat duty of Patrol Bombing Squadron One Hundred Nine in the Western Pacific, 20 April 1945-15 August 1945 Theodore Manning Steele Follow this and additional works at: http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his Recommended Citation Steele, Theodore Manning, "A pictorial record of the combat duty of Patrol Bombing Squadron One Hundred Nine in the Western Pacific, 20 April 1945-15 August 1945" (1946). World War Regimental Histories. 101. http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/101 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the World War Collections at Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. It has been accepted for inclusion in World War Regimental Histories by an authorized administrator of Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 110° ato• 0 c H N A ~ DOES N01 ~ u- tlnl~ ~lifO 71HA ~' .... \ \ "''".!... ~ ', '~ \ ' ' ' .... ' .... .... ~ " ',"-'. ', \ ' ' ... \ ' ' ' ... ' \ • ·MMH ' ', \ ' ~... \ ' ' ' ~ '' .. \ ' ...... ' ':..\ INDO ':..- -- -rat-~1»4.. CHlNA ..... ---- ' . --- ---~-- ....... ~ :)-- -- --- -<.- --- --- GUAM ----- -~:------- --).. ~- ----- ->-- - --- I ·~· ·:: \~:' TRUK :l ~ J.;. A PICTORIAL RECORD of the combat duty of PATROL BOMBING SQUADRON ONE HUNDRED NINE in the _Western Pacific, 20 April1945- 15 August 1945 DEDICATED ( ' ' .. C.0 4" • . • • .. .. .. .. .~ · .. .: .. :: ~ .. :::: .. ; ~ ;."~ · . .. ~ ~ "' ... to the officers and men of the squadron who ' Ill,,. •• .. ...... ... ' .a . ... .. == ~ : > <~ :~ .£ ::~ .. ! .. :· . .. .. ~ . .. - .. gave their lives that we may live in peace II .,.' • &. ~ " Copyright 1946 By Lieutenant Theodore M. Steele, USNR General Offset Co., Inc., New York 13, N.Y. "SKIPPER" LIEUTENANT COMMANDER GEORGE LEIGHTON HICKS USNR Executive Officer 2 August 1943-2 September 1944 Commanding Officer .... ... ........ ., . ~ .. .. .... .. 6 December 1944- 19 October 1945 . -

Army Abbreviations

Army Abbreviations Abbreviation Rank Descripiton 1LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1SG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST BGLR FIRST BUGLER 1ST COOK FIRST COOK 1ST CORP FIRST CORPORAL 1ST LEADER FIRST LEADER 1ST LIEUT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST LIEUT ADC FIRST LIEUTENANT AIDE-DE-CAMP 1ST LIEUT ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT ASST SURG FIRST LIEUTENANT ASSISTANT SURGEON 1ST LIEUT BN ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT BATTALION ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT REGTL QTR FIRST LIEUTENANT REGIMENTAL QUARTERMASTER 1ST LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST MUS FIRST MUSICIAN 1ST OFFICER FIRST OFFICER 1ST SERG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST SGT FIRST SERGEANT 2 CL PVT SECOND CLASS PRIVATE 2 CL SPEC SECOND CLASS SPECIALIST 2D CORP SECOND CORPORAL 2D LIEUT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2D SERG SECOND SERGEANT 2LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2ND LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 3 CL SPEC THIRD CLASS SPECIALIST 3D CORP THIRD CORPORAL 3D LIEUT THIRD LIEUTENANT 3D SERG THIRD SERGEANT 3RD OFFICER THIRD OFFICER 4 CL SPEC FOURTH CLASS SPECIALIST 4 CORP FOURTH CORPORAL 5 CL SPEC FIFTH CLASS SPECIALIST 6 CL SPEC SIXTH CLASS SPECIALIST ACTG HOSP STEW ACTING HOSPITAL STEWARD ADC AIDE-DE-CAMP ADJT ADJUTANT ARMORER ARMORER ART ARTIF ARTILLERY ARTIFICER ARTIF ARTIFICER ASST BAND LDR ASSISTANT BAND LEADER ASST ENGR CAC ASSISTANT ENGINEER ASST QTR MR ASSISTANT QUARTERMASTER ASST STEWARD ASSISTANT STEWARD ASST SURG ASSISTANT SURGEON AUX 1 CL SPEC AUXILARY 1ST CLASS SPECIALIST AVN CADET AVIATION CADET BAND CORP BAND CORPORAL BAND LDR BAND LEADER BAND SERG BAND SERGEANT BG BRIGADIER GENERAL BGLR BUGLER BGLR 1 CL BUGLER 1ST CLASS BLKSMITH BLACKSMITH BN COOK BATTALION COOK BN -

RAF Stories: the First 100 Years 1918 –2018

LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to the box for other visitors. RAF Stories: The First 100 Years 1918 –2018 Founding partner RAF Stories: The First 100 Years 1918–2018 The items in this case have been selected to offer a snapshot of life in the Royal Air Force over its first 100 years. Here we describe some of the fascinating stories behind these objects on display here. Case 1 RAF Roundel badge About 1990 For many, their first encounter with the RAF is at an air show or fair where a RAF recruiting van is present with its collection of recruiting brochures and, for younger visitors, free gifts like this RAF roundel badge. X004-5252 RAF Standard Pensioner Recruiter Badge Around 1935 For those who choose the RAF as a career, their journey will start at a recruiting office. Here the experienced staff will conduct tests and interviews and discuss options with the prospective candidate. 1987/1214/U 5 Dining Knife and Spoon 1938 On joining the RAF you would be issued with a number of essential items. This would have included set of eating irons consisting of a knife, fork and spoon. These examples have been stamped with the identification number of the person they were issued to. 71/Z/258 and 71/Z/259 Dining Fork 1940s The personal issue knife, fork and spoon set would not always be necessary. This fork would have been used in the Sergeant’s Mess at RAF Henlow. It is the standard RAF Nickel pattern but has been stamped with the RAF badge and name of the station presumably in an attempt to prevent individuals claiming it as their personal item. -

Guide to Abbreviations on Listing (PDF)

Guide to Abbreviations on Listing Branch Abbreviation Description AAF Army Air Force ARMY United States Army CA C‐ARMY Canadian Army CG Civil Civilian ColAr Colonial Army Indian MILI Colonial Militia NAVY United States Navy RANG Colonial Ranger USMC United States Marine Corps Rank Abbreviation Description 1LT First Lieutenant 1SG First Sergeant 2LT Second Lieutenant AM3 Aircraft Structural Mechanic 3rd Class AMM2 Aviation Machinist's Mate 2nd Class AV CAviationC Aviation Cadet AVO3 Avionics Officer AvR3 AvRd3 AW2 Aviation ASW Operator 2nd Class BM1 Boatswain's Mate 1st Class CAPT / CPT Captain CPL Corporal CTM Cryptologic Technician CTO2 Cryptologic Technician 2nd Class DC2 Damage Controlman 2nd Class ELM3 ENS Ensign (Colonial, Lieutenant 2nd Class) FL O Flight Officer FO 1 GM3 Gunner's Mate 3rd Class GuM Gunner's Mate HA2 LT Lieutenant LTC Lieutenant Colonel LTJG Lieutenant, Junior Grade M1C Mechanic 1st Class www.co.armstrong.pa.us MAJ Major MECH Mechanic MM1 Machinist's Mate First Class MMM MP5 MSG Master Sergeant MUSC Musician PFC Private First Class PO2 Petty Officer 2nd Class (Canadian Forces) PSG Platoon Sergeant PVT Private QMS Quartermaster Sergeant Rad1 Rad3 S1C Se2 SEA SGT Sergeant SM1 Signalman 1st Class SM2 Signalman 2nd Class SOL Soldier (Colonial Militia) SP4 Specialist 4th Class SRe Seaman Recruit SSG Staff Sergeant SURG Surgeon T4 TEC4 Technician 4th Class TEC5 Technician 5th Class TSG Technical Sergeant Status Abbreviation Description DNB Died, Non‐Battle DNBA DNBG DNBI Died, Non‐Battle (Influenza) DOW Died of Wounds DOWG KIA Killed in Action KIAF Killed in Action (Findings of Death) KIAM Killed in Action (Missing) KIAS Killed in Action (Sinking) MIA Missing in Action POWd Prisoner of War (Died in Captivity) www.co.armstrong.pa.us. -

Master Gunner George Marshall U.S.N

1 Master Gunner George Marshall U.S.N. Demetrios Constantinos Andrianis 2 Early Life……………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Brig Jefferson………………………………………………………………...…………………………….....4 Sloop-of-War Erie.…...…………………………………………..……..…………………………………....5 Gosport Navy Yard (1820-1824)………………………………………………………….………………… 6 North Carolina 74……….……………………………………………………………………………………8 Washington Navy Yard….……………………………………………………………………………….....10 Gosport Navy Yard (1832-1855)………………………...………………………………………………….11 Memorial ……………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Notes…………………………...…………………………………….……………………………...…........16 Contact: [email protected] Updated: May 31, 2021 May 18, 2021 All Rights Reserve 3 Early Life George Marshall was a Greek-American naval hero. He served during the War of 1812. He was an author, artillery scientist, chemist, and naval educator. Marshall was a warrant officer. His specialization was gunnery. He wrote Marshall's Practical Marine Gunnery. Marshall eventually became a master gunner in the U.S. Navy. Master was the highest rank a gunner could obtain. His son and sons-in-law also became gunners. He was one of the most important naval gunners in U.S. history. He helped build the framework of U.S. naval gunnery education. His book on naval gunnery outlined, artillery propulsion, over fifty chemical mixtures for pyrotechnics, Greek fire, smoke bombs, three different chemical mixtures for dying clothes, and the chemical composition of a stain removal solution. The book also lists the chemical names of dozens of different substances used in the early nineteenth century predating Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table and the standard chemical nomenclature of the 20th century. Marshall was born on the Greek island of Rhodes in 1781. Marshall was in the United States around the time America fought the First Barbary War. The country was 31 years old. He married Phillippi Higgs. -

Johnson Lieutena

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with Farnham J. “Gunner” Johnson Lieutenant, Marine Corps, World War II. 1996 OH 543 1 OH 543 Johnson, Farnham J. (1924-2001). Oral History Interview, 1996. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 35 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 35 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder) Military Papers: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder) Abstract: Farnham “Gunner” Johnson, an Appleton, Wisconsin native, discusses his service as a 1st lieutenant in the Marine Corps during World War II with the Fleet Marine Force Pacific Forward Echelon and with the Guam Island Command. Johnson mentions his family moved from Minnesota to Appleton (Wisconsin) when he was age one because his father, a dentist and World War I Marine Corps veteran, left the Veterans Administration Hospital where he had been working to open his own dental practice. Johnson mentions he graduated from St. Mary’s High School in Menasha (Wisconsin) in 1941 and attended the University of Wisconsin in the fall, where he played on the football team. He recalls hearing about the bombing of Pearl Harbor in the football dormitory and being one of the few who knew where Pearl Harbor was located. Johnson discusses at length his football career at the University of Wisconsin, in the Marine Corps, and as a professional with the Chicago Bears and the All American Football Conference’s Chicago Rockets. In 1941, Johnson states the University of Wisconsin made ROTC compulsory for all male students; he describes doing ROTC drills in the livestock pavilion. -

The Rank Insignias of the Netherlands Armed Forces Table of Contents | the Rank Insignias of the Netherlands Armed Forces

The rank insignias of the Netherlands armed forces Table of contents | The rank insignias of the Netherlands armed forces ROYAL NETHERLANDS NAVY ROYAL NETHERLANDS ARMY ROYAL NETHERLANDS AIR FORCE ROYAL NETHERLANDS MARECHAUSSEE FORMS OF ADDRESS IN THE ARMED FORCES This brochure was published by: Netherlands Ministry of Defence Directorate of Communication April 2016 Graphic design/photography: Defence Media Centre | The Hague Royal Netherlands Navy The ranks have been grouped according to their rank group (Dag- and general oFcers, senior oFcers, junior oFcers, NCOs, corporals and other ranks). In the RNLN, a corporal is classed as an NCO. A distinction is made between the insignias of NCOs and other ranks of the Deet and those of the marine corps. Admiral Vice Admiral Rear Admiral Commodore For the marines, the chevrons (V shaped symbols) have a red border. General Lieutenant Major General Brigadier (Marine corps) General (Marine corps) General (Marine corps) (Marine corps) Captain Commander Lieutenant Lieutenant Lieutenant Sub- Warrant Chief PeXy PeXy OFcer Commander Junior Grade Lieutenant OFcer OFcer Colonel Lieutenant Major Captain First Second Warrant Sergeant Sergeant (Marine corps) Colonel (Marine corps) (Marine corps) Lieutenant Lieutenant OFcer Major (Marine corps) (Marine corps) (Marine corps) (Marine corps) (Marine corps) (Marine corps) Leading Rating Able Rating Ordinary Rating Junior Rating Corporal Marine Marine Marine (Marine corps) Class 1 Class 2 (Marine corps) (Marine corps) (Marine corps) Royal Netherlands Army The ranks have been grouped according to their rank group (general oFcers, senior oFcers, junior oFcers, NCOs, corporals and other ranks). For cavalry and military administration units, the insignias of the ranks of General Lieutenant Major Brigadier corporal up to and including sergeant major are in silver braid. -

Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Codenames

Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Codenames AASF Advanced Air Striking Force Abigail bombing campaign against selected German towns ( autumn 1940) a/c aircraft AC Army Co-operation (squadron) ACAS Assistant Chief of the Air Staff A/C/M Air Chief Marshal ADGB Air Defence of Great Britain ADI (K) Assistant Directorate of Intelligence (Department K) AEAF Allied Expeditionary Air Forces AFC Air Force Cross AFDU Air Fighting Development Unit AFHQ RCAF Headquarters, Ottawa AFU Air Fighting Unit AGLT Automatic Gun-Laying Turret Al airborne interception radar or Air Intelligence ALO Air Liaison Officer A/M Air Marshal AMP Air Member for Personnel AOC Air Officer Commanding AO-in-c Air Officer-in-Chief AOC-in-c Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief AOP Air Observation Post APC Armament Practice Camp API air position indicator Argument concentrated attack on German aircraft production (February 1944) ASR air-sea rescue ASSU Air Support Signals Unit ASV Air to Surface Vessel (radar) A/V/M Air Vice-Marshal B-bomb buoyant bomb Barbarossa German attack on Soviet Union (June 1941) xiv Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Codenames BCATP British Commonwealth Air Training Plan BdU Befehlshaber der U-boote (U-boat Headquarters) BDU Bombing Development Unit Benito German night-fighter control system Berlin German AI radar Bernhardine data transmission system used for German night-fighter control Big Ben v-2 rocket Bodenplatte Luftwaffe attack on Allied airfields in Northwest Europe (1 January 1945) Bombphoon Hawker Typhoon modified for employment as a fighter-bomber Boozer -

Name Rank Age Name Rank Age Name Rank Age Name Rank Age

NAME RANK AGE NAME RANK AGE NAME RANK AGE NAME RANK AGE BUTLER Private 37 Lance ALMOND Private 32 DALLIMORE Sergeant 25 GLEW Corporal BUTLER Private 32 APPLETON Private 28 Air Mechanic GOOCH Major 36 DANZEY 20 2nd Class CALLINGHAM Private 19 Second ARCHER Private 19 GOODFELLOW 29 DAVIS Private 27 Lieutenant CARTER Trooper 24 Second ASKER Private 18 Lance GRANT 19 Lieutenant CHANEY Private 24 DENYER 25 Corporal AYRES Sergeant 26 GREGORY Private 19 CHAPLIN Private 27 EARLE Corporal 25 BAKER Private 39 HANCOCK Gunner 32 CHAPLIN Private 27 FANCOURT Private 21 BOLTON Gunner 24 HANCOCKS Rifleman 24 CHITTY Drummer 21 FERRIS Private 21 BOULT Sergeant 38 HARLEY Lieutenant 35 FLETCHER Private 34 BOWYER Private 18 CHURCH Gunner 35 HARRIS Private 19 FREEMAN Private 22 BOWYER Private 38 CLARK Private 21 HARVEY Corporal 32 GAMBRIEL Private 25 Petty COLE Private 21 BROOKER 41 Officer HEATH Sergeant 28 GIBBINS Private 24 Stoker COLE Private 21 HEATH Private 27 BROWN Private 37 GILES Gunner 22 Lance COLLINSON 28 Corporal HOLLINGS Corporal 28 BROWN Private 21 GILKERSON Private 24 COOPER Private 25 Field Stoker 1st HOLLOWAY Private 39 BROWNLOW 84 GILKERSON 27 Marshal Class COURT Sergeant 24 HOLLY Private 22 Leading BURGES Colonel 54 GILKERSON 23 Seaman NAME RANK AGE NAME RANK AGE NAME RANK AGE NAME RANK AGE NAME RANK AGE POCOCK Private 26 WHARTON Private 18 SMITH Sergeant 27 HOPE Private 35 LYFORD-PRIOR Private 18 PROCTOR Corporal 32 WHITE Private 26 HOWARD Private 23 MARTIN Private 19 SMITH Private 20 Second WIGGETT 19 Lance Lieutenant PURSER 32 HOWELL -

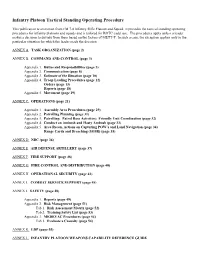

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure

Infantry Platoon Tactical Standing Operating Procedure This publication is an extract from FM 7-8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad. It provides the tactical standing operating procedures for infantry platoons and squads and is tailored for ROTC cadet use. The procedures apply unless a leader makes a decision to deviate from them based on the factors of METT-T. In such a case, the exception applies only to the particular situation for which the leader made the decision. ANNEX A. TASK ORGANIZATION (page 2) ANNEX B. COMMAND AND CONTROL (page 3) Appendix 1. Duties and Responsibilities (page 5) Appendix 2. Communication (page 8) Appendix 3. Estimate of the Situation (page 10) Appendix 4. Troop Leading Procedures (page 12) Orders (page 13) Reports (page 18) Appendix 5. Movement (page 19) ANNEX C. OPERATIONS (page 21) Appendix 1. Assembly Area Procedures (page 29) Appendix 2. Patrolling Planning (page 31) Appendix 3. Patrolling: Patrol Base Activities; Friendly Unit Coordination (page 32) Appendix 4. Conduct an Ambush and Hasty Ambush (page 33) Appendix 5. Area Recon, Actions on Capturing POW’s and Land Navigation (page 34) Range Cards and Breaching (SOSR) (page 35) ANNEX D. NBC (page 36) ANNEX E. AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY (page 37) ANNEX F. FIRE SUPPORT (page 38) ANNEX G. FIRE CONTROL AND DISTRIBUTION (page 40) ANNEX H OPERATIONAL SECURITY (page 43) ANNEX I. COMBAT SERVICE SUPPORT (page 45) ANNEX J. SAFETY (page 48) Appendix 1. Reports (page 49) Appendix 2. Risk Management (page 51) Tab 1. Risk Assessment Matrix (page 52) Tab 2. Training Safety List (page 53) Appendix 3. -

Australian Gunner Obituary Resource

AUSTRALIAN GUNNER OBITUARY RESOURCE Major General Herbert William Lloyd, CB, CMG, CVO, DSO, ED White Eagle of Siberia, 3 MIDs. (18 August1883 – 10 August 1957) By Brigadier R. M. Thompson, DSO, MC (Reproduced in part from RAA Liaison Letter Second Edition 1992 With additions by Peter Bruce) Herbert William (Bertie) Lloyd was born in South Yarra on August 18, 1883. He was the only child of Irish-born parents William Lloyd, a mounted constable (later Sergeant) in the Victoria Police and his wife Fanny Henrietta, (Nee Mills). Bertie’s early education was at Thomas Palmer’s University High School and later at Wesley College. He started work as a clerk with the Commonwealth Treasury and was commissioned in the Australian Field Artillery in 1906 and appointed militia adjutant AFA Victoria in 1908 and promoted Captain in 1909. In March 1910, entered the Permanent Military Forces and was posted to 1 Field Battery RAFA as Battery Captain 1913. In May 1914 Lloyd married Meredith Pleasents (d. 1952) in Redfern, Sydney. Lloyd proceeded overseas as Captain and Adjutant of 1 Field Brigade, 1 Australian Division, 1st AIF in the first convoy of 1914 – World War I. He landed at Cape Helles, Gallipoli, in April 1915 with the regiment which supported 29 British Division. He was subsequently promoted to Major to command 1 Field Battery and was awarded the DSO. After the evacuation of all forces from Gallipoli he became Brigade Major 2 Div Arty, 1atr AIF stationed at Tel-el-Kebir. His ardour and training capacity MADE 2 Div Arty. 2 Div Arty left the Suez Canal area in March 1916 and went into action near Armentieres, France on 1st April 1916.RAAHC Lloyd was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel to command 5 Field Brigade, 2 Aust Division of which I was a member and he became my CO.