The Munich Air Crash and Its Different Narrations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

That You May Know

THIS BOOK RECORDS THE DESCENDANTS OF WILLIAM GREGG TEE FRIEND IMMI GRANT TO DELAWARE 1682 FROM WHICH NUCLEUS DISSEMINATED NESTS OF GREGGS TO PENNSYLVANIA, VIRGINIA, AND NORTH CAROLINA. That you may know: ·'Tis no sinister nor no awkward claun Picked from wormholes of long vanished days, Nor from the dust of old oblivion rak'd, He sends you the most memorable line, ~ every branch truly demoruitrative." -King Henry V Published by HAZEL_~~,l'4W~',:;:"~ :,;Jt'NDALL - .. ....,.J 'of'{ J!b;,. l, ~,_"J'E ...:> i'B,Jl.Jl, 1: ANDEE...<:tON, ·!Ni")tA:NA 19H That you may know: ·'Tis no sinister nor no awkward claun Picked from wormholes of long vanished days, Nor from the dust of old oblivion rak'd, He sends you the most memorable line, ~ every branch truly demoruitrative." -King Henry V TO ALL OUR GREGGS. A debt of gratitude is due the author of th.is volume !or making accessible to members and friends of the Gregg family something of the origin, history, ai;tivt ties, and personalities of this numerous and widely distributed kinship. The work. is the result of years of patient, persistent effort entailing a vast amount o:f re search, correspondence, travel, and expense, which have been expended with enthusiasm and determination. The record should appeal to all who have an interest in i1onorable ancestry, family tradition, and worthy acbieve!ltent, · If should be an inspiration to noble e!:fort and high aspiration. , · In the collection of rdiable data concerning events of the distant past, the law of diminishing returns appears to operate. -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended 30 June 2018 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 001-35627 MANCHESTER UNITED plc (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Not Applicable (Translation of Company’s name into English) Cayman Islands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Sir Matt Busby Way, Old Trafford, Manchester, England, M16 0RA (Address of principal executive offices) Edward Woodward Executive Vice Chairman Sir Matt Busby Way, Old Trafford, Manchester, England, M16 0RA Telephone No. 011 44 (0) 161 868 8000 E-mail: [email protected] (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A ordinary shares, par value $0.0005 per share New York Stock Exchange Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act. None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

Arsenal.Com Thearsenalhistory.Com

arsenal.com Se11so11 1951-8 Footballthearsenalhistory.com League Division I Saturday, lst February ARSENAL v. MANCHESTER UNITED 'KICK-OFF 3 p.m. (Part Floodlight) lors who had come particularly to see our friendly match at Hereford last April and ARSENAL FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED new signings-Ronnie Clayton and Freddie when we approached our old colleague Joe Jones-both from Hereford United. Here Wade, who is man;iger of the team nowa Directors again it was a story of the goalkeeper days, it was arranged that we should talk SIR BRACBWBLL :>Mira, Bart., K.C.V.O. (C hairman) keeping down the score, for Maclaren in about it again after they had been elimin CoMMANDBR A. F. BoNB, R.o., R.N.R., asro. 1he City goal was in great form to make ated from the F.A. Cup. This we did after J. W. JOYCE, EsQ. spectacular saves from Ray Swallow, Tony the 3rd Round and everything was fixed D. J. C. H. HILL-WOOD, EsQ. G. BRAcswsu.-SMITH, EsQ., M.B.B., e.A . Biggs and Freddie Jones. up in very quick time. We wish these two Secretary First, he made a full-length, one-handed youngsters every success at Highbury and W .R. WALL. save from Jones and followed it up with a long sojourn with our club. Manager a backward somersault in saving from Last Saturday we played a Friendly W. J. CRAYSTON. Biggs. Then Newman, the centre-half, match at Swansea in most difficult con kicked off the line when a shot from Swal ditions. The thaw had set in and the pitch low seemed certain to go in and Mac was thoroughly wet and sloppy. -

Class of 1959 55 Th Reunion Yearbook

Class of 1959 th 55 Reunion BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY 55th Reunion Special Thanks On behalf of the Offi ce of Development and Alumni Relations, we would like to thank the members of the Class of 1959 Reunion Committee Michael Fisher, Co-chair Amy Medine Stein, Co-chair Rosalind Fuchsberg Kaufman, Yearbook Coordinator I. Bruce Gordon, Yearbook Coordinator Michael I. Rosen, Class Gathering Coordinator Marilyn Goretsky Becker Joan Roistacher Blitman Judith Yohay Glaser Sally Marshall Glickman Arlene Levine Goldsmith Judith Bograd Gordon Susan Dundy Kossowsky Fern Gelford Lowenfels Barbara Esner Roos Class of 1959 Timeline World News Pop Culture Winter Olympics are held in Academy Award, Best Picture: Marty Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy Elvis Presley enters the US music charts for fi rst Summer Olympics are held in time with “Heartbreak Hotel” Melbourne, Australia Black-and-white portable TV sets hit the market Suez Crisis caused by the My Fair Lady opens on Broadway Egyptian Nationalization of the Suez Canal Th e Wizard of Oz has its fi rst airing on TV Prince Ranier of Monaco Videocassette recorder is invented marries Grace Kelly Books John Barth - Th e Floating Opera US News Kay Th ompson - Eloise Alabama bus segregation laws declared illegal by US Supreme Court James Baldwin - Giovanni’s Room Autherine Lucy, the fi rst black student Allen Ginsburg - Howl at the University of Alabama, is suspended after riots Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 signed into law for the construction of 41,000 miles of interstate highways over a 20-year period Movies Guys and Dolls Th e King and I Around the World in Eighty Days Economy Gallon of gas: 22 cents Average cost of a new car: $2,050 Ground coff ee (per lb.): 85 cents First-class stamp: 3 cents Died this Year Connie Mack Tommy Dorsey 1956 Jackson Pollock World News Pop Culture Soviet Union launches the fi rst Academy Award, Best Picture: Around the World space satellite Sputnik 1 in 80 Days Soviet Union launches Sputnik Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story debuts on 2. -

Silva: Polished Diamond

CITY v BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY SILVA: POLISHED DIAMOND 38008EYEU_UK_TA_MCFC MatDay_210x148w_Jan17_EN_P_Inc_#150.indd 1 21/12/16 8:03 pm CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 52 Fans: Your Shout 6 Pep Guardiola 54 Fans: Supporters 8 David Silva Club 17 The Chaplain 56 Fans: Junior 19 In Memoriam Cityzens 22 Buzzword 58 Social Wrap 24 Sequences 62 Teams: EDS 28 Showcase 64 Teams: Under-18s 30 Access All Areas 68 Teams: Burnley 36 Short Stay: 74 Stats: Match Tommy Hutchison Details 40 Marc Riley 76 Stats: Roll Call 42 My Turf: 77 Stats: Table Fernando 78 Stats: Fixture List 44 Kevin Cummins 82 Teams: Squads 48 City in the and Offi cials Community Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcoffi cial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Offi cer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE, Tudor Thomas | Life President Bernard Halford Manager Pep Guardiola | Assistants Rodolfo Borrell, Manel Estiarte Club Ambassador | Mike Summerbee | Head of Football Administration Andrew Hardman Premier League/Football League (First Tier) Champions 1936/37, 1967/68, 2011/12, 2013/14 HONOURS Runners-up 1903/04, 1920/21, 1976/77, 2012/13, 2014/15 | Division One/Two (Second Tier) Champions 1898/99, 1902/03, 1909/10, 1927/28, 1946/47, 1965/66, 2001/02 Runners-up 1895/96, 1950/51, 1988/89, 1999/00 | Division Two (Third Tier) Play-Off Winners 1998/99 | European Cup-Winners’ Cup Winners 1970 | FA Cup Winners 1904, 1934, 1956, 1969, 2011 Runners-up 1926, 1933, 1955, 1981, 2013 | League Cup Winners 1970, 1976, 2014, 2016 Runners-up 1974 | FA Charity/Community Shield Winners 1937, 1968, 1972, 2012 | FA Youth Cup Winners 1986, 2008 3 THE BIG PICTURE Celebrating what proved to be the winning goal against Arsenal, scored by Raheem Sterling. -

Irish Football Association Annual Report 2018-2019

IRISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 WWW.IRISHFA.COM 2018-19 CONTENTS President’s Introduction 3 Chief Executive’s Report 6 Stadium Report 9 Irish FA Annual Report Irish FA International Senior Men’s Team 13 International Men’s U21 19 2 International Men’s U19 And U17 20 International Senior Women’s Team 23 International Women’s U19 And U17 26 Girls’ Regional Excellence Programme 29 Elite Performance Programme - Club NI 30 The International Football Association Board (IFAB) 32 Domestic Football Irish Cup 33 Domestic Football 35 Domestic Football Club Licensing And Facilities 36 Refereeing 39 Grassroots Programmes 40 Disability Football Special Education 42 Disability Football Activities 43 Grassroots Football In Schools 44 Domestic Football Women’s Club Football 46 Grassroots Club And Volunteer Development 48 Grassroots Futsal 50 Community Relations 51 Northern Ireland Boys’ Football Association 52 Northern Ireland Schools’ Football Association 54 Communications 56 Finance 57 The Irish Football Association’s Annual Report 2018-19 was compiled, edited and written by Nigel Tilson PRESIDENT’S Annual Report Irish FA INTRODUCTION The depth and breadth of the work we as an association undertake never ceases to amaze me. 2018-19 Initiatives such as our Ahead of the Game mental The U19 men’s side narrowly missed out on health programme and our extensive work with VIEGLMRKERIPMXIVSYRHMR9)YVSWUYEPMƤIVW8LI disabled players are just some of the excellent U17s did manage it, however they found the going things that we do. tough in an elite round mini tournament staged in the Netherlands. And it was great that we received a Royal seal of 3 approval when the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge The senior women’s team bounced back following visited the National Football Stadium at Windsor ETSSV;SVPH'YTUYEPMƤGEXMSRGEQTEMKRF] Park, and our headquarters, back in February. -

DANIEL Mcdonnell Mcclean Uncovered

Irish Independent 2 SportSoccer Saturday 11 November 2017 DANIEL McDONNELL McClean uncovered The star of Ireland’s World Cup tilt has always polarised opinions. But who is James McClean? A journey to Top: The mural of the Ireland winger in Creggan as part of their ‘local heroes’ Creggan in theme NORTH WEST NEWSPIX. Above: One of the pictures which forms part of a photo history of Bloody Sunday located near the centre of the Derry estate Derry to meet HIS is Creggan. It’s To the right of the profile of Friday lunchtime and O’Doherty, there is a sketch of Tony O’Doherty is Olympic boxer Charlie Nash. his friends and pacing up and down in To the left, there is an artist’s his usual spot outside impression of Creggan’s most family shines T the Corned Beef Tin, famous sporting son, with a the area’s community centre on flame-coloured border tracing Central Drive. his distinctive features. It’s a a light on the The 70-year-old is wearing his proud Irishman with an 11 on the Derry City jacket because he will chest and a face that appears to later function as head steward at be roaring in celebration. James man behind the final home game of the season McClean is instantly recognisable. for a club where he served as both Around these parts, there are the headlines player and manager. constant reminders that he is one In Creggan, he has the presence of their own. In truth, it only takes of a manager on the sideline, a matter of seconds. -

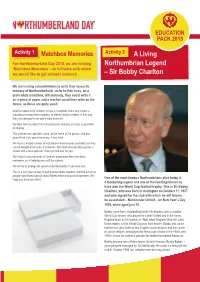

Sir Bobby Charlton

EDUCATION PACK 2019 Activity 1 Matchbox Memories Activity 2 A Living For Northumberland Day 2019, we are running Northumbrian Legend ‘Matchbox Memories’ - an initiative with which we would like to get schools involved. – Sir Bobby Charlton We are inviting schoolchildren to write their favourite memory of Northumberland, so far in their lives, on a plain white matchbox. Alternatively, they could write it on a piece of paper and a teacher could then write on the boxes, as these are quite small. Another option is for children to take a matchbox home and collect a matchbox memory from a parent, or elderly family member. In this way, they can take part in an oral history exercise. We then wish to collect the memory boxes and put as many as possible on display. The children can add their name, or the name of the person who has given them their special memory, if they wish. We have a limited number of matchbox memory boxes available, but they can be bought at Amazon, if needs be. We could also possibly partner a school with a local sponsor, if we can find one for you. We’d love to have pictures of children working on their matchbox memories, or all holding one aloft for a photo. We will try to arrange for certain collection points, if you take part. This is a very special way to being generations together and find out what people have found special about Northumberland, past and present. We hope you have fun with it. One of the most famous Northumbrians alive today is a footballing legend and one of the few Englishmen to have won the World Cup football trophy. -

The Greatest History by «Manchester United»

УДК 796.332(410.176.11):811.111 Kostykevich P., Mileiko A. The greatest history by «Manchester United» Belarusian National Technical University Minsk, Belarus Manchester United are an English club in name and a У global club in nature. They were the first English side to playТ in the European Cup and the first side to win it, and they are the only English side to have become world club champions.Н In addition, the Munich Air Disaster of 1958, which wiped out one of football's great young sides, changed the clubБ indelibly. The club was founded in 1878 as Newton Heath LYR Football Club by workers at the Lancashire and Yorkshire 1 й Railway Depot . They played in the Football League for the first time in 1892, but were relegated иtwo years later. The club became Manchester United in 1902,р when a group of local businessmen took over. It was then that they adopted the red shirt for which United would оbecome known. The new club won theirт first league championships under Ernest Mangnall in 1908 and 1911, adding their first FA Cup in 1909. Mangnall left toи join Manchester City in 1911, however, and there would зbe no more major honours until after the Second World War. In that timeо United had three different spells in Division Two, beforeп promotion in 1938 led to an extended spell in the top flight. The key to that was the appointment of the visionary Matt еBusby in 1945. Busby reshaped the club, placing Рcomplete faith in a youth policy that would prove astonishingly successful. -

A Perfect Script? Manchester United's Class of '92. Journal of Sport And

Citation: Dart, J and McDonald, P (2017) A Perfect Script? Manchester United’s Class of ‘92. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 41 (2). pp. 118-132. ISSN 1552-7638 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516685272 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/3425/ Document Version: Article (Accepted Version) The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. This is the pre-publication version To cite this article: Dart, J. and McDonald, P. (2016) A Perfect Script? Manchester United’s Class of ’92 Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 1-17 Article first published online: December 23, 2016 To link to this article: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516685272 A Perfect Script? Manchester United's Class of ‘92 Abstract The Class of ‘92 is a documentary film which features six Manchester United F.C. -

Manchester United PRE-INTERMEDIATE 3

Penguin Readers Answer Key level Manchester United PRE-INTERMEDIATE 3 Answers to book activities Answers to Factsheet activities e In 1966 f In 1966 Activities before reading the book g In Northern Ireland 1a division Open answers h On 1 January 1974 b cup i In 1955 c score Activities while reading the book j He was playing for Torino. d manage Pages 1–11 k Eric Cantona e pitch 1a The final was played in Barcelona. l He acted in films. f spirit b Solskjaer scored the winner. m In 1991 g scout c There are 90,000 fans in the n Posh Spice, Victoria Adams h tactics stadium. 3a iv 2–4 Open answers d Sixteen million fans watched the b viii 5a Open answers game in Britain. c v b Four. One at the beginning of the e They won the cup in 1968. d vi two halves and one after each of f Beckham took both the corners. e i the two goals. 2a A million fans welcomed the team f iii c To get fit and to practise their skills. home. g vii d A team of players who are younger b Alex Ferguson h ii than the adult teams. c Two. The other is Manchester City. 6 Open answers d A businessman called John Davies Pages 28–41 7a Bobby Charlton e In 1909 1a The Cliff b Open answer. The Leeds fans were f £60,000 b Five or six days a week unhappy because Cantona left their g In 1945 c In July team to join Manchester United. -

God, King, and Dennis

Watson poem 5/19/06 8:39 PM Page 65 God, and King, and Denis Law written on hearing – incorrectly– that Tony Blair was a Manchester City fan, for Trevor Griffiths, who really is As I lay asleep in Germany, there came a voice from over the sea, and with great power it forth led me to walk in the visions of Poesy. When the dust had settled on Utopia and the Dulux gloss had hardened to a cold pale blue, the people’s government found they had some fine tuning to do. Curt directives came from Downing Street: the Free Trade Hall in Manchester was to be renamed the Mike Summerbee Mall; the National Anthem became ‘Swing Lee Sweet Chariot’; Trevor Griffiths was appointed as Poet Laureate; the Hallé Orchestra would be re-constituted as the Freddie and the Dreamers Revival Band; relegation from the Premier League was to be suspended – just to be on the safe side. But when fighting broke out along Denis Law Way, as the Peace Line had recently been called, the Leader of the Opposition in the upper house, Lord Stiles of Stretford End, roundly condemned Queen Camilla, who the day before had called in at the Manchester City Superstore (formerly Harrods of Oxford Street). There she had praised the new legislation that had given merchandising access to those not fortunate enough to live in the North West. As she took a Colin Bell memento mug and a Frank Swift replica jersey from the rack, Watson poem 5/19/06 8:39 PM Page 66 she announced that she, the previous week at Sotheby’s, had been the mystery buyer behind the bid for Bert Trautmann’s 1958 Cup Final neck brace (in honour of her husband’s German stiff-upper-neck ancestors).