University of California Santa Cruz Quantum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Fellow Quantum Mechanics;

Dear Fellow Quantum Mechanics Jeremy Bernstein Abstract: This is a letter of inquiry about the nature of quantum mechanics. I have been reflecting on the sociology of our little group and as is my wont here are a few notes. I see our community divided up into various subgroups. I will try to describe them beginning with a small group of elderly but distinguished physicist who either believe that there is no problem with the quantum theory and that the young are wasting their time or that there is a problem and that they have solved it. In the former category is Rudolf Peierls and in the latter Phil Anderson. I will begin with Peierls. In the January 1991 issue of Physics World Peierls published a paper entitled “In defence of ‘measurement’”. It was one of the last papers he wrote. It was in response to his former pupil John Bell’s essay “Against measurement” which he had published in the same journal in August of 1990. Bell, who had died before Peierls’ paper was published, had tried to explain some of the difficulties of quantum mechanics. Peierls would have none of it.” But I do not agree with John Bell,” he wrote,” that these problems are very difficult. I think it is easy to give an acceptable account…” In the rest of his short paper this is what he sets out to do. He begins, “In my view the most fundamental statement of quantum mechanics is that the wave function or more generally the density matrix represents our knowledge of the system we are trying to describe.” Of course the wave function collapses when this knowledge is altered. -

Multi-Dimensional Entanglement Transport Through Single-Mode Fibre

Multi-dimensional entanglement transport through single-mode fibre Jun Liu,1, ∗ Isaac Nape,2, ∗ Qianke Wang,1 Adam Vall´es,2 Jian Wang,1 and Andrew Forbes2 1Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics, School of Optical and Electronic Information, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430074, Hubei, China. 2School of Physics, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Wits 2050, South Africa (Dated: April 8, 2019) The global quantum network requires the distribution of entangled states over long distances, with significant advances already demonstrated using entangled polarisation states, reaching approxi- mately 1200 km in free space and 100 km in optical fibre. Packing more information into each photon requires Hilbert spaces with higher dimensionality, for example, that of spatial modes of light. However spatial mode entanglement transport requires custom multimode fibre and is lim- ited by decoherence induced mode coupling. Here we transport multi-dimensional entangled states down conventional single-mode fibre (SMF). We achieve this by entangling the spin-orbit degrees of freedom of a bi-photon pair, passing the polarisation (spin) photon down the SMF while ac- cessing multi-dimensional orbital angular momentum (orbital) subspaces with the other. We show high fidelity hybrid entanglement preservation down 250 m of SMF across multiple 2 × 2 dimen- sions, demonstrating quantum key distribution protocols, quantum state tomographies and quantum erasers. This work offers an alternative approach to spatial mode entanglement transport that fa- cilitates deployment in legacy networks across conventional fibre. Entanglement is an intriguing aspect of quantum me- chanics with well-known quantum paradoxes such as those of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) [1], Hardy [2], and Leggett [3]. -

Unity Consciousness: a Quantum Biomechanical Foundation

Theoretical UNITY CONSCIOUSNESS: A QUANTUM BIOMECHANICAL FOUNDATION Thomas E. Beck, Ph.D. & Janet E. Colli, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Citing research in consciousness, quantum physics, biophysics and cosmology, we propose the collective amplification of quantum effects as the basis for scientifically describing Kundalini awakening, and the higher-order, emergent phenomenon of Unity consciousness, Such alterations of consciousness have their origin in quantum-scale processes, such as self-induced transparency, superradiance, superpositions, quantum tunneling, and Bose-Einstein condensa tion, Microtubules are considered to be key components in non-local, quantum processes critical to human consciousness, We postulate that bundles of fibers (neural cells), each containing numerous microtubule "lasers" acting in unison, collectively result in a massive surge of light energy to the brain, The sudden onset and radically altered nature of such states are consis tent with a model based on the activation of a laser. The liquid crystalline nature of the human body likely provides a foundation for the non-local aspect ofVniry consciousness, The unifYing paradigm of the "quantum hologram" is introduced ro apply quantum properties to macroscopic events, KEYWORDS: Uniry consciousness, kundalini, microtubules, non-local communication, Bose-Einstein condensate, liquid crystals, dark matter, zero-point energy Subtle Energies & Energy Medicine • Volume 14 • Number 3 • Page 267 INTRODUCTION he history of humanity has been irreversibly altered by a relative few individuals who have attained the highest state of consciousness known T to humankind: Unity consciousness, described as a merging with the Oneness of all Creation. The historical figures of Buddha ("the illumined one"), Jesus Christ, and the contemporary spiritual leader, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, exemplity those who have contributed to uplifting consciousness through their enlightenment. -

On Monte Carlo Time-Dependent Variational Principles

On Monte Carlo Time-Dependent Variational Principles Von der QUEST-Leibniz-Forschungsschule der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universit¨atHannover zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften { Doctor rerum naturalium { genehmigte Dissertation von FABIANWOLFGANGG UNTERTRANSCHEL¨ Geboren am 10.01.1987 in Gehrden 2016 0 Erstpr¨ufer : Prof. Dr. Reinhard F. Werner Zweitpr¨ufer : Prof. Dr. Klemens Hammerer Beratendes Mitglied des Pr¨ufungsausschusses : Prof. Dr. Tobias J. Osborne Vorsitzender des Pr¨ufungsausschusses : Prof. Dr. Rolf Haug Tag der Promotion: 17. Dezember 2015 On Monte Carlo Time-Dependent Variational Principles Fabian W. G. Transchel Abstract The present dissertation is concerned with the development and implementation of a novel scheme for quantitative, numeric approximation of the dynamics of quantum lattice systems based on the Time-Dependent Variational Principle together with Monte Carlo techniques in order to include dissipative interactions. The specific implementation is demonstrated on both common and not yet in-detail explored Heisenberg- and Fermi-Hubbard models in one and two dimensions. Additionally, the technical requirements regarding computational complexity and capacity are discussed, especially with regards toward parallelizable components of the imple- mentation. Concluding remarks include prospects with respect to application and extension of the presented methods. Keywords: Monte Carlo method, Dissipative Dynamics, Lindblad Equation iii Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Dissertation befasst sich mit der Entwicklung und Umsetzung eines neuartigen Schemas zur quantitativen numerischen N¨aherung der Dynamik von Quantengittersystemen auf Grundlage des zeitabh¨angigenVariationsprinzips unter Zuhilfenahme von Monte-Carlo-Techniken zur Einbeziehung von dissipativen Wech- selwirkungen. Die Implementierung wird anhand von Beispielen f¨urHeisenberg- und Fermi-Hubbard-Modellen in einer und zwei Dimensionen gezeigt und erl¨autert. -

![Arxiv:1107.3800V2 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 30 Nov 2011 Uzigfaue,Sc Stemdfiaino Elt Ythe by Reality of Ment](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8628/arxiv-1107-3800v2-physics-hist-ph-30-nov-2011-uzigfaue-sc-stemd-aino-elt-ythe-by-reality-of-ment-408628.webp)

Arxiv:1107.3800V2 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 30 Nov 2011 Uzigfaue,Sc Stemdfiaino Elt Ythe by Reality of Ment

Quantum magic: A skeptical perspective Giorgio Torrieri FIAS, J.W. Goethe Universit¨at, Frankfurt A.M., Germany torrieri@fias.uni-frankfurt.de Quantum mechanics (QM) has attracted a considerable amount of mysticism, in public opinion and even among academic researches, due to some of its conceptually puzzling features, such as the modification of reality by the observer and entangle- ment. We argue that many popular ”quantum paradoxes” stem from a confusion be- tween mathematical formalism and physics; We demonstrate this by explaining how the paradoxes go away once a different formalism, usually inconvenient to perform calculations, is used. we argue that some modern developments, well-studied in the research literature but generally overlooked by both popular science and teaching- level literature, make quantum mechanics (that is, ”canonical” QM, not extensions of it) less conceptually problematic than it looks at first sight. When all this is looked at together, most “puzzles” of QM are not much different from the well-known paradoxes from probability theory. Consequently, “explanations of QM” involving physical action of consciousness or an infinity of universes are ontologically unnecessary arXiv:1107.3800v2 [physics.hist-ph] 30 Nov 2011 2 I. INTRODUCTION All the way from its origins, the theory of quantum mechanics (QM) [1] has enjoyed a resounding experimental success, but has elicited unease regarding its philosophical impli- cations, and place as a scientific theory. A lot of research effort on the part of distinguished scientists [2–4] (founders of QM among them! [5–8]) has gone into “interpreting” quantum mechanics. This effort has produced quite a few candidates for interpretation, ranging from the sensible but ambiguous Copenhagen interpretation (“quantum variables only refer to what can be known to us, rather than any objective reality”) esoteric ideas (such as “many universes” and a role of consciousness in quantum physics), less ontologically troublesome extensions (“hidden variables”) as well as quite a few “paradoxes”. -

What Is Consciousness? Artificial Intelligence, Real Intelligence, Quantum Mind, and Qualia

What Is Consciousness? Artificial Intelligence, Real Intelligence, Quantum Mind, And Qualia Stuart A. Kauffman1 and Andrea Roli2,3 1Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, USA 2Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Campus of Cesena, Alma Mater Studiorum Universit`adi Bologna 3European Centre for Living Technology, Venezia, Italy July 24, 2021 Abstract We approach the question \What is Consciousness?" in a new way, not as Descartes' \systematic doubt", but as how organisms find their way in their world. Finding one's way involves finding possible uses of features of the world that might be beneficial or avoiding those that might be harmful. \Possible uses of X to accom- plish Y" are “Affordances”. The number of uses of X is indefinite (or unknown), the different uses are unordered and are not deducible from one another. All biological adaptations are either affordances seized by heritable variation and selection or, far faster, by the organism acting in its world finding uses of X to accomplish Y. Based on this, we reach rather astonishing conclusions: (1) Artificial General Intelligence based on Universal Turing Machines (UTMs) is not possible, since UTMs cannot “find” novel affordances. (2) Brain-mind is not purely classical physics for no classi- cal physics system can be an analogue computer whose dynamical behavior can be isomorphic to \possible uses". (3) Brain mind must be partly quantum|supported by increasing evidence at 6.0 sigma to 7.3 Sigma. (4) Based on Heisenberg's interpre- tation of the quantum state as \Potentia" converted to \Actuals" by Measurement, a natural hypothesis is that mind actualizes Potentia. -

Scientific Report for the Year 2000

The Erwin Schr¨odinger International Boltzmanngasse 9 ESI Institute for Mathematical Physics A-1090 Wien, Austria Scientific Report for the Year 2000 Vienna, ESI-Report 2000 March 1, 2001 Supported by Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, Austria ESI–Report 2000 ERWIN SCHRODINGER¨ INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MATHEMATICAL PHYSICS, SCIENTIFIC REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2000 ESI, Boltzmanngasse 9, A-1090 Wien, Austria March 1, 2001 Honorary President: Walter Thirring, Tel. +43-1-4277-51516. President: Jakob Yngvason: +43-1-4277-51506. [email protected] Director: Peter W. Michor: +43-1-3172047-16. [email protected] Director: Klaus Schmidt: +43-1-3172047-14. [email protected] Administration: Ulrike Fischer, Eva Kissler, Ursula Sagmeister: +43-1-3172047-12, [email protected] Computer group: Andreas Cap, Gerald Teschl, Hermann Schichl. International Scientific Advisory board: Jean-Pierre Bourguignon (IHES), Giovanni Gallavotti (Roma), Krzysztof Gawedzki (IHES), Vaughan F.R. Jones (Berkeley), Viktor Kac (MIT), Elliott Lieb (Princeton), Harald Grosse (Vienna), Harald Niederreiter (Vienna), ESI preprints are available via ‘anonymous ftp’ or ‘gopher’: FTP.ESI.AC.AT and via the URL: http://www.esi.ac.at. Table of contents General remarks . 2 Winter School in Geometry and Physics . 2 Wolfgang Pauli und die Physik des 20. Jahrhunderts . 3 Summer Session Seminar Sophus Lie . 3 PROGRAMS IN 2000 . 4 Duality, String Theory, and M-theory . 4 Confinement . 5 Representation theory . 7 Algebraic Groups, Invariant Theory, and Applications . 7 Quantum Measurement and Information . 9 CONTINUATION OF PROGRAMS FROM 1999 and earlier . 10 List of Preprints in 2000 . 13 List of seminars and colloquia outside of conferences . -

![Arxiv:1805.06871V2 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 21 May 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5874/arxiv-1805-06871v2-physics-hist-ph-21-may-2018-725874.webp)

Arxiv:1805.06871V2 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 21 May 2018

VISITING NEWTON'S ATELIER BEFORE THE PRINCIPIA, 1679-1684. MICHAEL NAUENBERG UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ Abstract. The manuscripts that presumably contained Newton's early development of the fundamental concepts that led to his Principia have been lost. A plausible recon- struction of this development is presented based on Newton's exchange of letters with Robert Hooke in 1679, with Edmund Halley in 1686, and on some clues in the diagram associated with Proposition1 in Book1 of the Principia that have been ignored in the past. The graphical method associated with this proposition leads to a rapidly conver- gent method to obtain orbital curves for central forces, and elucidates how Newton may have have been led to formulate some of his other propositions in the Principia.. 1. Introduction The publication of Newton's masterpiece, \Mathematical Principles of Natural Philos- ophy" known as Principia [1], marks the beginning of modern theoretical Physics and Astronomy. It was regarded as a very difficult book by his contemporaries, and also by modern readers. In 1687 when the Principia was first published, it was claimed that only a handful of readers in Europe were competent to read it [2]. John Locke, for example, found the demonstrations impenetrable, and asked Christiaan Huygens if he could trust them. When Huygens assured him that he could, \he applied himself to the prose and digested the physics without the mathematics" [3]. Shortly after the release of the Principia a group of students at Cambridge supposedly were heard by Newton to say, \here goes a man who has written a book that neither he nor anyone else understands" [4]. -

Gerald Holton Wins Pais Prize by Daniel M

History Physics NEWSLETTER A F o r u m o F T h e A m e r i c A n P h y s i cof A l s o c i e T y • V o l u m e X • n o . 4 • s P r i n G 2 0 0 8 Gerald Holton Wins Pais Prize By Daniel M. Siegel, Chair, Pais Prize Selection Committee, and David C. Cassidy he American Physical Society and the American an NSF-sponsored national curriculum-development project Institute of Physics have chosen Gerald Holton to co-directed by Holton. With its textbook, films, laboratory Treceive the 2008 Abraham Pais Prize for the History of exercises, and other materials, the Course brought physics, Physics “for his pioneering work in the history of physics, as seen through its history, to some 200,000 high school especially on Einstein and relativity. students a year. The book still exists His writing, lecturing, and leader- in a revised edition titled Under- ship of major educational projects standing Physics (Springer, 2002), introduced history of physics to a coauthored with David Cassidy and mass audience.” Holton joins previ- James Rutherford. This project not ous winners Martin J. Klein, John only influenced an entire generation L. Heilbron, and Max Jammer in of physics students and educators, receiving this distinguished prize, but it also inspired recent initiatives which will be awarded to him dur- by the NSF, the National Research ing the April 2008 APS meeting in Council, and the American Associa- St. Louis. tion for the Advancement of Science After receiving a certificate of to improve U.S. -

Skeptic Redesign

ARTICLE Quantum Consciousness and Other Spooky Myths Quantum mechanics is mysterious. Consciousness is mysterious. The thought that there may be a connection has led to a lot of quantum biological pseudoscience. BY MARTIN BIER ABOUT A HUNDRED YEARS HAVE PASSED since coordinate axes are not to be thought of as tangible quantum mechanics was first developed. Quantum geometrical objects with real directions in three di- mechanics proved very successful in describing mensional space. They are part of a mathematical what is happening on the atomic level. The emission model in which there may be infinitely many such of light by objects when they are heated up (e.g., a axes. There is no equation that describes the col- light bulb), spectral lines, and later things like super- lapse. The numerical outcome of the observation conductivity, superfluidity, and the laser could be depends on which of the coordinate axes the wave well understood and described with quantum me- function collapses on. It is only probabilities that chanics. are associated with the different coordinate axes Quantum mechanics is not an approximation or that can be derived from Schrödinger’s equation. an ad hoc trick to make the equations agree with real- “Observation” is a somewhat vague notion and ity and with each other. It is a fundamental theory many physicists have a problem with its central role that is supposed to describe what is really happening in quantum mechanics. Furthermore, the element at the subatomic level. A wave function is the basis of of randomness in the collapse of the wave function the theory and Schrödinger's equation, named after is troublesome, and led to Einstein’s famous remark the German physicist Erwin Schrödinger, explains that “God does not play dice.” Richard Feynman, in the evolution of that wave function over time. -

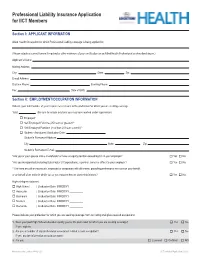

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members Section I: APPLICANT INFORMATION Allied Health Occupation for which Professional Liability coverage is being applied for: (Please attach a current license if required or other evidence of your certification as anAllied Health Professional as described above.) Applicant’s Name: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: E-mail Address: Daytime Phone: Evening Phone: Fax: Date of Birth: Section II: EMPLOYMENT/OCCUPATION INFORMATION Indicate your total number of years experience relevant to the profession for which you are seeking coverage. Total: (Be sure to include any time you may have worked under supervision) o Employed* o Self-Employed Full-time (25 hours or greater)** o Self-Employed Part-time (less than 25 hours a week)** o Student - Anticipated Graduation Date: Student’s Permanent Address: City: State: Zip: Student’s Permanent E-mail: *Are you or your spouse also a shareholder or have an equity position exceeding 5% in your employer? o Yes o No *Are you incorporated (including Sub chapter S Corporations), a partner, owner or officer to your employer? o Yes o No **Are there any other individuals, employed or associated with otherwise, providing professional services on your behalf, or on behalf of an entity in which you or your spouse has an ownership interest? o Yes o No Highest degree obtained: o High School | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Associate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Bachelors | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Masters | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Doctorate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ Please indicate your profession for which you are seeking coverage from our listing of eligible covered occupations: ______________________________________ 1. -

Science Beyond Enchantment Revisiting the Paradigm of Re-Enchantment As an Explanatory Framework for New Age Science

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR LITTERATUR, IDÉHISTORIA OCH RELIGION Science Beyond Enchantment Revisiting the Paradigm of Re-enchantment as an Explanatory Framework for New Age Science Kristel Torgrimsson Termin VT-17 Kurs: RKT 250, 30 hp Nivå: Master Handledare: Jessica Moberg Abstract A common understanding of scientists within the New Age movement is that they are manifesting a form of re-enchantment and that their ideas should be addressed as natural theologies. This understanding often takes as its reference point, the re-entanglement of science and religion whose original separation, in this case, is often the working definition of disenchantment. This essay argues that many contemporary scientists who are both popular references and active participants on New Age conferences cannot fully be accounted for by this paradigm. Among these scientists and more particularly those interested in quantum physics, there are many who wish to extend the quantum phenomena not only to support questions of religious character, but to develop theories on physical reality and human nature. Their ambitions are not solely about merging science and religion but also about suggesting new scientific solutions and discussing scientific dilemmas. The purpose of this essay has therefore been to find a viable alternative to the re-enchantment paradigm that offers a more detailed description of their ideas. By opting instead for a radically revised re-enchantment paradigm and an anthropological suggestion for studying minor sciences, this essay has found that a more precise definition of popular New Age scientists could be as (1) “problematic” to the epistemological and ontological underpinnings of the disenchantment of the world, where the problem is not necessarily restricted to the separation of religion and science, and (2) as being a minor science, which entails a critique and challenge to state science, albeit not necessarily in terms of imposing religion on the grounds of science.