Review of Andrew Ashbee, the Harmonious Music of John Jenkins, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

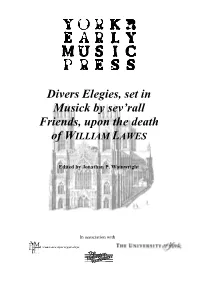

Divers Elegies, Set in Musick by Sev'rall Friends, Upon the Death

Divers Elegies, set in Musick by sev’rall Friends, upon the death of WILLIAM LAWES Edited by Jonathan P. Wainwright In association with Divers Elegies, set in Musick by sev’rall Friends, upon the death of William Lawes Edited by Jonathan P. Wainwright Page Introduction iii Editorial Notes vii Performance Notes viii Acknowledgements xii Elegiac texts on the death of William Lawes 1 ____________________ 1 Cease, O cease, you jolly Shepherds [SS/TT B bc] Henry Lawes 11 A Pastorall Elegie to the memory of my deare Brother William Lawes 2 O doe not now lament and cry [SS/TT B bc] John Wilson 14 An Elegie to the memory of his Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes, servant to his Majestie 3 But that, lov’d Friend, we have been taught [SSB bc] John Taylor 17 To the memory of his much respected Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes 4 Deare Will is dead [TTB bc] John Cobb 20 An Elegie on the death of his Friend and Fellow-servant, M r. William Lawes 5 Brave Spirit, art thou fled? [SS/TT B bc] Edmond Foster 24 To the memory of his Friend, M r. William Lawes 6 Lament and mourne, he’s dead and gone [SS/TT B bc] Simon Ives 25 An Elegie on the death of his deare fraternall Friend and Fellow, M r. William Lawes, servant to his Majesty 7 Why in this shade of night? [SS/TT B bc] John Jenkins 27 An Elegiack Dialogue on the sad losse of his much esteemed Friend, M r. -

Jouer Bach À La Harpe Moderne Proposition D’Une Méthode De Transcription De La Musique Pour Luth De Johann Sebastian Bach

JOUER BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE PROPOSITION D’UNE MÉTHODE DE TRANSCRIPTION DE LA MUSIQUE POUR LUTH DE JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MARIE CHABBEY MARA GALASSI LETIZIA BELMONDO 2020 https://doi.org/10.26039/XA8B-YJ76. 1. PRÉAMBULE ............................................................................................. 3 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 3. TRANSCRIRE BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE, UN DÉFI DE TAILLE ................ 9 3.1 TRANSCRIRE OU ARRANGER ? PRÉCISIONS TERMINOLOGIQUES ....................................... 9 3.2 BACH TRANSCRIPTEUR ................................................................................................... 11 3.3 LA TRANSCRIPTION À LA HARPE ; UNE PRATIQUE SÉCULAIRE ......................................... 13 3.4 REPÈRES HISTORIQUES SUR LA TRANSCRIPTION ET LA RÉCEPTION DES ŒUVRES DE BACH AU FIL DES SIÈCLES ....................................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Différences d’attitudes vis-à-vis de l’original ............................................................. 15 3.4.2 La musique de J.S. Bach à la harpe ............................................................................ 19 3.5 LES HARPES AU TEMPS DE J.S. BACH ............................................................................. 21 3.5.1 Panorama des harpes présentes en Allemagne. ......................................................... 21 4. CHOIX DE LA PIECE EN VUE D’UNE TRANSCRIPTION ............................... -

Rebecca Kellerman Petretta, Soprano Charles Humphries, Counter-Tenor

THE TUESDAY CONCERT SERIES THE CHURCH OF THE EPIPHANY Since Epiphany was founded in 1842, music has played a vital at Metro Center role in the life of the parish. Today, Epiphany has two fine musical instruments which are frequently used in programs and worship. The Steinway D concert grand piano was a gift to the church in 1984, in memory of parishioner and vestry member Paul Shinkman. The 64-rank, 3,467-pipe Æolian- Skinner pipe organ was installed in 1968 and has recently been restored by the Di Gennaro-Hart Co. It was originally given in memory of Adolf Torovsky, Epiphany’s organist and choirmaster for nearly fifty years. HOW YOU CAN HELP SUPPORT THE SERIES 1317 G Street NW Washington, DC 20005 www.epiphanydc.org The Tuesday Concert Series reaches out to the entire [email protected] metropolitan Washington community. Most of today’s free- Tel: 202-347-2635 will offering goes directly to WBC but a small portion helps to defray the cost of administration, advertising, instrument upkeep and the securing of outstanding performers for this concert series. We ask you to consider a minimum of $10. UESDAY ONCERT ERIES However, please do consider being a Sponsor of the Tuesday T C S Concert Series at a giving level that is comfortable for you. 2013 Our series is dependent on your generosity. For more information about supporting or underwriting a complete concert, please contact the Rev. Randolph Charles at 202- 347-2635 ext. 12 or [email protected]. To receive a 15 APRIL 2014 weekly email of the upcoming concert program, email Rev. -

Notes – RECORDER CONSORT VIOLS Trotto (Anon Italian 14Th Century) Is a Lively Monophonic Dance in the Form of a Rondeau

- Notes – RECORDER CONSORT VIOLS Trotto (Anon Italian 14th century) is a lively monophonic dance in the form of a rondeau. It originated around 1390.The time signature for the trotto is given as 6/8, Richard Mico (1590-1661) and John Jenkins (1592-1678) are celebrated fantasy and is infused with the triple meter swing, kind of like listening to horse riding and composers. This form is rather like an instrumental madrigal in which several points fox hunting. In Italian, trotto means to trot. of imitation are developed one after the other. Jenkins is our favourite composer, an inexhaustibly inventive melodist and a consummate contrapuntist. Like many of the English fantasy composers and like Haydn, Jenkins resided on the estates of the Virgo Rosa ( Gilles Binchois 1400-1460) provincial gentry; he preferred to be treated as a gentleman house-guest of Lord Gilles Binchois was a Franco-Flemish composer, one of the earliest members of the Dudley North (an amateur treble viol player) rather than an employee. Burgundian School, and one of the three most famous composers of the early 15th century. Binchois is often considered to be the finest melodist of the 15th century, Clive Lane is a Sydney based composer, with published works for viols and writing carefully shaped lines which are easy to sing, and utterly memorable. Most of recorders. He is also an accomplished singer and viol player, and is member of our his music, even his sacred music, is simple and clear in outline. consort. Air is a composition for quartet of viols (treble/tenor/tenor/bass) in a 16 th century style, in which Clive captures the mood of a viol piece by his favourite The words of this sacred motet - composer for viols: John Jenkins. -

Emma Kirkby Soprano Anthony Rooley Lute

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Emma Kirkby Soprano Anthony Rooley Lute THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 4, 1982, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN The English Orpheus A Contention between Hope and Despair ...................... JOHN DOWLAND Fantasia ............................................. ALFONSO FERRABOSCO Grief, keep within ........................................... JOHN DANYEL Pavan ....................................................... FERRABOSCO Thou Mighty God .............................................. DOWLAND Semper Dowland, semper dolens ................................. DOWLAND Sweet birds deprive us never ................................ JOHN BARTLETT INTERMISSION Come, shepherds come \ Perfect and endless circles are! ............................... WILLIAM LAWES Love I obey J I rise and grieve } The Lark J ..................................... HENRY LAWES A tale out of Anacreon j Stript of their green \ What a sad fate J .......................... HENRY PURCELL When first Amintas sued for a kiss) Mr. Rooley: London, Decca, Hyperion, and L'Oiseau Lyre Records. Miss Kirkby: Decca and Hyperion Records. Twelfth Concert of the 104th Season Special Concert About the Artists Anthony Rooley studied for three years at the Royal Academy of Music where his love of history and philosophy led him to study the music of the Renaissance. He owned his first lute in 1968 and later combined it with voice and viol to form The Consort of Musicke, one of today's leading specialist Renaissance ensembles. The ensemble covers all the major secular music of the period 1450-1650, with special emphasis in recent years on the English repertoire circa 1600. One major project to emanate from the Consort is a 21-record set of the "Complete Works of John Dowland," which has received accolades from critics throughout the world. In addition to the Consort, which is nearly a full-time concern, Mr. -

Download Booklet

2 CD John Jenkins as the occasion required; he was apparently JOHN JENKINS (1592-1678) Four Part Consort Music never officially attached to any household, for COMPLETE FOUR-PART CONSORT MUSIC his pupil Roger North wrote: “I never heard that Amateur viol players throughout the world love he articled with any gentleman where he playing the consort music of John Jenkins, resided, but accepted what they gave him.” probably more than any other English composer of the great golden era of music for multiple We can guess that they must have been quite viols, that ranges from William Cornyshe in advanced players in that much of the music CD1 CD2 1520 through to Henry Purcell in 1680. And was highly virtuosic in the division style, where 1 Fantasia No. 1 [3.24] 1 Fantasia No. 10 [3.58] the reason why is not hard to fathom: a rare slow-moving lines are decorated by ‘dividing’ the 2 Fantasia No. 2 [3.57] 2 Fantasia No. 11 [3.30] melodic gift is married to an exceptionally deep longer notes into ever shorter ones. However, the 3 Fantasia No. 3 [4.03] 3 Fantasia No. 12 [4.18] understanding of harmony and modulation; consort style was mostly concerned with more effortless counterpoint gives each part an melodic, mellifluous lines and Jenkins wrote a 4 Fantasia No. 4 [3.39] 4 Fantasia No. 13 [3.16] equal voice in the musical conversation; and large body of such music for four, five and six viols. 5 5 Pavan in D Minor [6.09] Fantasia No. -

Spring 2021 PROGRAM #: EMN 20-42 RELEASE

Early Music Now with Sara Schneider Broadcast Schedule — Spring 2021 PROGRAM #: EMN 20-42 RELEASE: April 5, 2021 Joyful Eastertide! This week's show presents an eclectic array of music to celebrate Easter, including motets by François Couperin, Jacob Obrecht, Antoine Busnois, and Orlando Gibbons. We'll also hear from two composers based in Hamburg: Matthias Weckmann and Thomas Selle. Our performers include Weser Renaissance Bremen, Capilla Flamenca, Cantus Cölln, and Henry's Eight. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-43 RELEASE: April 12, 2021 Treasures from Dendermonde The music of Hildegard of Bingen has come down to us in only two sources, one of which is known as the Dendermonde Codex, named after the abbey in the Belgian town where it is now housed. We'll hear Psallentes, a Belgian ensemble specializing in chant, performing selections from this codex. We'll also hear them singing 14th and 15th century chant from Tongeren. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-44 RELEASE: April 19, 2021 Recent Releases We're sampling a couple of exciting recent releases this week! The Mad Lover features sonatas, suites, grounds, and various bizzarie from 17th century England performed by Théotime Langlois de Swarte (violin) and Thomas Dunford (lute). We'll also hear from Ensemble Morgaine, with tracks from their 2021 release Evening Song, which focuses on 16th century hymns, songs, and Psalms from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. PROGRAM #: EMN 20-45 RELEASE: April 26, 2021 Petrucci and the Odhecaton Ottaviano Petrucci was a printer working in Venice at the turn of the 16th century. He revolutionized the distribution of music and cultivated a taste for the Franco-Flemish style in Italy with the publication of Harmonice Musices Odhecaton in 1501. -

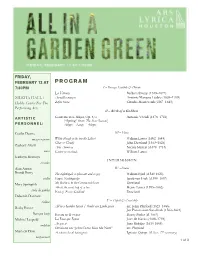

Garden Green Program Notes

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 12 AT PROGRAM 7:30PM I – Breezes Earthly & Divine La Vittoria Barbara Strozzi (1619–1677) wfihe^=e^ii=L= Ayreçillos manços António Marques Lésbio (1639–1709) Hobby Center For The Zefiro torna Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) Performing Arts = II – Birth of a Goddess ARTISTIC Concerto in E Major, Op. 8/1 Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) (“Spring” from The Four Seasons) PERSONNEL: Allegro – Largo – Allegro Cecilia Duarte III – Flora mezzo-soprano White though ye be (on the Lilies) William Lawes (1602–1645) Clear or Cloudy John Dowland (1563–1626) Zachary Averyt Aria Amorosa Nicola Matteis (c1670–1714) tenor Gather ye rosebuds William Lawes Kathryn Montoya INTERMISSION recorder Alan Austin IV –Fauna Brandi Berry The nightingale so pleasant and so gay William Byrd (c1540-1623) violin Engels Nachtegaeltje Jacob van Eyck (c1590–1657) Mary Springfels My Robin is to the Greenwood Gone Dowland About the sweet bag of a bee Henry Lawes (1595–1662) viola da gamba Earl of Essex Gaillard Dowland Deborah Dunham violone V – Cupid & Courtship Becky Baxter All in a Garden Green / Onder een Linde groen arr. John Playford (1623–1686) Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Baroque harp Sonata in G major Henry Butler (d. 1652) Michael Leopold La Rosa que Reyna Juan de Navas (c1650-1719) Ay que si Juan Hidalgo (1614-1685) archlute Divisions on “John Come Kiss Me Now” arr. Playford Matthew Dirst A señores los de buen gusto Ignacio Quispe (fl. late 17th century) harpsichord !1 of !3 PROGRAM NOTES Songs about spring have been around since the dawn of human history, when our ancestors first gave thanks for bright sunshine, warm breezes, gentle rain, and flowering plants. -

British Viol Consort Fretwork to Play Old and New Music at CMA October 12

British viol consort Fretwork to play old and new music at CMA October 12 by Daniel Hathaway You could say with some accuracy that Fretwork, the British viol consort, was an idea formed in Hell. Its early members Richard Boothby, Bill Hunt, and Richard Campbell first played together in the underworld scene in Monteverdi’s Orfeo, a production semi-staged in Barcelona in 1985 by Andrew Parrott’s Taverner Players. Those three minutes led to further performances, and now Fretwork is considered among the premier viol ensembles in the world. Most viol consorts stick to old music composed before the viola da gamba became extinct in England in the latter part of the 17th century. Fretwork is unusual in its equal embrace of contemporary music: on its website the group lists two dozen composers who have written works for them. Fretwork’s current five members, Asako Morikawa, Reiko Ichise, Sam Stadien, Emily Ashton, and Boothby (far right in the photo) will appear on the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Performing Arts series in Gartner Auditorium on Wednesday, October 12 at 7:30 pm. The program includes 16th and 17th century English consort music by John Taverner and Orlando Gibbons, works by contemporary composers Nico Muhly and Gavin Bryars, and a special performance of Norwegian composer Maja Ratkje’s River Mouth Echoes. Cleveland is one of ten cities Fretwork will visit on an American Tour that begins on October 6 in Montréal and ends on October 24 in Victoria, BC, with stops in Boston, Milwaukee, Wake Forest in North Carolina, Jackson in Mississippi, Austin and Lubbock in Texas, and Vancouver BC. -

The Silken Tent Clare Wilkinson Soprano Fretwork

The Silken Tent Clare Wilkinson soprano Fretwork 1 1 Where the Blind and Wanton Boy William Byrd 2 Auf ein altes Bild Hugo Wolf 3 Now Each Flowery Bank of May Orlando Gibbons 4 The Garden Stephen Wilkinson 5 La fille aux cheveux de lin, from Preludes, Book 1, L. 117 Claude Debussy 6 Turn Our Captivity, O Lord William Byrd 7 O Solitude, Z.406a Henry Purcell 8 O Waly, Waly, from Folk Song Arrangements, Vol. 3, “British Isles” Benjamin Britten Three Sonnetts and Two Fantasias, Op. 68: Alexander Goehr 9 Sonnet CXVI: Let Me Not to the Marriage 0 Fantasia I q The Silken Tent w Fantasia II e Sonnet LXXVI: Why Is My Verse so Barren? r O Lord, in Thy Wrath Orlando Gibbons t Music for a While Henry Purcell y Sleep Peter Warlock u Lord, to Thee I Make My Moan William Byrd i-o Prelude and Fugue in C Major, Op. 87 Dmitri Shostakovich p O Lord, Make Thy Servant Elizabeth William Byrd a Gebet Hugo Wolf s Heimweh, from Lyric Pieces, Book 6, Op. 57 Edvard Grieg d At the Manger Stephen Wilkinson f If (From “The Diary of Anne Frank”) Michael Nyman 2 The Silken Tent is quite unsuited to viols; but this opening (and closing) section is intense, deeply melancholy and contained, which suits viols down to the ground. Until quite recently it was thought that the viola da gamba died with the death of one its most loved exponents, Charles Frederick Abel, in At either end of the time spectrum, there is music written specifically 1787; and that it was literally buried with the composer in St Pancras for viols. -

An Examination of the Seventeenth-Century English Lyra

An examination of the seventeenth-century English lyra viol and the challenges of modern editing Volume 1 of 2 Volume 1 Katie Patricia Molloy MA by Research University of York Music January 2015 Abstract This dissertation explores the lyra viol and the issues of transcribing the repertoire for the classical guitar. It explores the ambiguities surrounding the lyra viol tradition, focusing on the organology of the instrument, the multiple variant tunings required to perform the repertoire, and the repertoire specifically looking at the solo works. The second focus is on the task of transcribing this repertoire, and specifically on how one can make it user-friendly for the 21st-century performer. It looks at the issues of tablature, and the issues of standard notation, and finally explores the notational possibilities with the transcription, experimenting with the different options and testing their accessibility. Volume II is a transliteration of solo lyra viol works by Simon Ives from the source Oxford, Bodleian Library Music School MS F.575. It includes a biography of Simon Ives, a study of the manuscript in question and describes the editorial procedures that were chosen as a result of the investigations in volume I. 2 Contents Volume I Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 6 Declaration 7 Introduction 8 1. The use of the term ‘lyra viol’ 12 2. The organology of the lyra viol 23 3. The tuning of the instrument 38 4. The lyra viol repertoire with specific focus on the solo works 45 5. The transcription of tablature 64 6. Experimentation with notation -

A1 JOHN JENKINS Fantasias

A1 JOHN JENKINS Fantasias: Nos. 1–12 a 6. In nomines: Nos. 1–2 a 6. Pavan in F. Bell Pavan in a • Phantasm (period instruments) • LINN 556 (Download: 66=07) JOHN WARD Fantasias: Nos. 1–7 a 6; Nos. 1–12 a 5. In nomines: Nos. 1–2 a 6; a 5 • Phantasm (period instruments) • LINN 339 (Download: 77=57) I am dealing with these two releases together because neither is new and both have been reviewed previously, though one of them, the Jenkins, not in its current incarnation. So let me sort things out. First, if a record labelʼs numbering scheme means anything, one assumes that the higher the number the more recent the recording. Not so in this case. The Jenkins release, bearing the number 556, was recorded in 2005; the Ward, bearing the number 339, was recorded in 2009. The Jenkins was originally released on Avie, the label under which Brian Robins reviewed it in 30=2, so we know this is a reissue on the Linn label. The Ward was reviewed by Barry Brenesal in 334, shortly after it was released as the same Linn BKD 339 as it appears here, so it has to be assumed that this is not a transfer from another label but an original Linn recording. This no doubt eXplains the higher number for the earlier recorded Jenkins: Linn acquired the Avie recording and reissued it on its own label in 2016, seven years after the Ward. This does not eXplain, however, why we are now seeing recordings made eight and 12 years ago, and previously reviewed, turn up for review again.