ED390064.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Missing in Action: Repression, Return, and the Post-War Uncanny 1

Notes 1 Missing in Action: Repression, Return, and the Post-War Uncanny 1. The First World War is commonly pointed to as a pivotal event that prompted writers to search for new literary forms and modes of expres- sion. Hazel McNair Hutchinson suggests that wartime themes of “anxiety, futility, fragmentation and introspection would extend into post-war writing and would become hallmarks of American Modernist literature.” The first world conflict produced novels such as John Dos Passos’ One Man’s Initiation: 1917 (1920) based on his experi- ences as a volunteer ambulance driver and Three Solders (1921), which investigates the war’s psychological impact. Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929) includes sparse yet graphic depictions of bat- tle, and his first novel Fiesta: The Sun Also Rises (1927) chronicles the aftermath of the war for those who were physically or emotion- ally wounded. Many major American authors of the 1920s and 1930s were personally impacted by the war, and it continually surfaces in the works of writers such as Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, e. e. cum- mings, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. For a brief discussion of American literature influenced by the First World War, see Hazel McNair Hutchison, “American Literature of World War One,” The Literary Encyclopedia (July 2, 2007), http:// www.litencyc.com/ php/ stop- ics.php?rec=true&UID=1735. 2. Maxwell Geismar, “The Shifting Illusion,” in American Dreams, American Nightmares, ed. David Madden (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1970), 53. 3. Richard Bessel and Dirk Schuman, eds., Life After Death: Approaches to a Cultural and Social History of Europe during the 1940s and 1950s (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 7. -

ED071097.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 071 097 CS 200 333 TITLE Annotated Index to the "English Journal," 1944-1963. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Champaign, PUB DATE 64 NOTE 185p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Renyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 47808, paper, $2.95 non-member, $2.65 member; cloth, $4.50 non-member, $4.05 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC -$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; Educational Resources; English Education; *English Instruction; *Indexes (Locaters); Periodicals; Resource Guides; *Scholarly Journals; *Secondary School Teachers ABSTRACT Biblidgraphical information and annotations for the articles published in the "English Journal" between 1944-63are organized under 306 general topical headings arranged alphabetically and cross referenced. Both author and topic indexes to the annotations are provided. (See also ED 067 664 for 1st Supplement which covers 1964-1970.) (This document previously announced as ED 067 664.) (SW) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. f.N... EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION Cr% THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. C.) DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- 1:f INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY r REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU C) CATION POSITION OR POLICY [11 Annotated Index to the English Journal 1944-1963 Anthony Frederick, S.M. Editorial Chairman and the Committee ona Bibliography of English Journal Articles NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERS OF ENGLISH Copyright 1964 National Council of Teachers of English 508 South Sixth Street, Champaign, Illinois 61822 PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPY RIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRLNTED "National Council of Teachers of English TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE US OFFICE OF EDUCATION FURTHER REPRODUCTION OUTSIDE THE ERIC SYSTEM REQUIRES PER MISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER English Journal, official publication for secondary school teachers of English, has been published by the National Council of Teachers of English since 1912. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

War and American Literature Edited by Jennifer Haytock Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49680-3 — War and American Literature Edited by Jennifer Haytock Frontmatter More Information WAR AND AMERICAN LITERATURE This volume examines representations of war throughout American literary history, providing a firm grounding in established criticism and opening up new lines of inquiry. Readers will find accessible yet sophisticated essays that lay out key questions and scholarship in the field. War and American Literature offers a comprehensive synthesis of the literature and scholarship of US war writing, illuminates how themes, texts, and authors resonate across time and wars, and pro- vides multiple contexts in which texts and a war’s literature can be framed. By focusing on American war writing, from the wars with the Native Americans and the Revolutionary War to the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, this volume illuminates the unique role repre- sentations of war have in the US imagination. is professor of English at SUNY Brockport. She has published At Home, At War: Domesticity and World War I in American Literature () and the Routledge Introduction to American War Literature () as well as works on twentieth- century American women writers. She is Brockport’s winner of the SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Scholarship. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49680-3 — War and American Literature Edited by Jennifer Haytock Frontmatter More Information Twenty-first-century America puzzles many citizens and observers. A frequently cited phrase to describe current partisan divisions is Lincoln’s “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” a warning of the perils to the Union from divisions generated by slavery. -

Autumn 2001 Varia

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 37 | Autumn 2001 Varia What We Keep: Time and Balance in the Brother Stories of John Cheever David Raney Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/587 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2001 Number of pages: 63-80 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference David Raney, « What We Keep: Time and Balance in the Brother Stories of John Cheever », Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 37 | Autumn 2001, Online since 30 September 2008, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/587 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved What We Keep: Time and Balance in the Brother Stories of John Cheever 1 What We Keep: Time and Balance in the Brother Stories of John Cheever David Raney 1 Tolstoy famously maintained in Anna Karenina that "All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way" (1). John Cheever, born two years after the Russian master died, spent much of his literary career examining both sorts, and the forces that drive wedges between family members or bind them together. Arlin Meyer has singled out as one of Cheever's consistent subjects "the family and the intricate web of emotional and moral concerns which compose it" (23-4). Among these concerns, one that Cheever explores in considerable depth in his short fiction is the relationship between brothers. Some of the brother pairs he creates are primarily sympathetic, others almost primordially antagonistic, but taken together they develop two of Cheever's main themes : a pervasive alienation from modern mass culture and, paradoxically, a deep distrust of nostalgia. -

Catalogue 13 2 Catalogue 13

CATALOGUE 13 2 CATALOGUE 13 1904 Coolidge Ave., Altadena, California 91001 · Tel. (626) 297-7700 · [email protected] www.WhitmoreRareBooks.com Books may be reserved by email: [email protected] and by phone: (626) 297-7700 We welcome collectors and dealers to come visit our library by appointment at: 1904 Coolidge Ave., Altadena, CA 91001 For our complete inventory, including many first editions, signed books and other rare items, please visit our website at: www.WhitmoreRareBooks.com Follow us on social media! @WRareBooks @whitmorerarebooks whitmorerarebooks Catalogue 13 1. Ars Moriendi Ars Moriendi ex varijs sententijs collecta... Nurmberge (Nuremberg): J. Weissenburger, [1510]. Octavo (159 × 123 mm). Modern green morocco, spine lettered in gilt, boards single ruled in blind, edges green. Housed in a custom-made green slipcase. 14 woodcuts (the first repeated). Engraved bookplate of Catherine Macdonald to the front pastedown. Minor toning, cut close at foot with loss of portions of the decorative borders, a very good copy. First of three Latin editions printed by Weissenburger. The book derives from the Tractatus (or Speculum) Artis Bene Moriendi, composed in 1415 by an anonymous Dominican friar, probably at the request of the Council of Constance. The Ars Morienda is taken from the second chapter of that work, and deals with the five temptations that beset a dying man (lack of faith, despair, impatience, spiritual pride, and avarice), and how to avoid them. It was first published as a block book around 1450 in the Netherlands, and it was among the first books printed with movable type. It continued to be popular into the 16th century. -

100 + Books for the College Bound 100 + Books for the College Bound TITLE LEXILE AUTHOR

100 + Books for the College Bound TITLE LEXILE AUTHOR Animal/Outdoors/Nature Dolphin Island 1000 Arthur C. Clarke Never Cry Wolf 1330 Farley Mowat Walden 1420 Henry David Thoreau Moby Dick 1200 Herman Melville The Call of the Wild 1170 Jack London White Fang 970 Jack London The Plague Dogs ? Richard Adams Watership Down 880 Richard Adams Kon-Tiki 1310 Thor Heyerdahl Beyond Belief And Then There Were None 570 Agatha Christie The Hound of the Baskervilles 1090 Arthur Conan Doyle Beowulf 1090 Seamus Heaney translation Dracula 1070 Bram Stoker The Turn of the Screw 1140 Henry James Frankenstein 1170 Mary Shelley The House of Seven Gables 1320 Nathaniel Hawthorne The Picture of Dorian Gray 920 Oscar Wilde Beloved 870 Toni Morrison British Literature The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie 1120 Muriel Spark The lnheritors ? William Golding Great Expectations 1200 Charles Dickens Oliver Twist 990 Charles Dickens Pride and Prejudice 1100 Jane Austen The Return of the Native 1040 Thomas Hardy Tess of the D’ Urbervilles ? Thomas Hardy Brighton Rock ? Graham Greene A Burnt out Case ? Graham Greene Fantasy/Science Fiction Brave New World 870 Aldous Huxley 2001: A Space Odyssey 1060 Arthur C. Clarke Anthem 880 Ayn Rand Flowers for Algernon 910 Daniel Keyes 1984 1090 George Orwell The Invisible Man 980 H.G. Wells The Fellowship of the Ring 860 J.R.R. Tolkien The Lost Horizon 1060 James Hilton Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea 1030 Jules Verne Cat's Cradle ? Kurt Vonnegut Slaughterhouse-Five 850 Kurt Vonnegut On the Beach 780 Nevil Shute Fahrenheit 451 890 Ray Bradbury The Martian Chronicles 740 Ray Bradbury Green Mansions ? W.H. -

Rhetorical and Narrative Structures in John Hersey's Hiroshima: How They Breathe Life Into the Tale of a Doomed City

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2004 Rhetorical and narrative structures in John Hersey's Hiroshima: How they breathe life into the tale of a doomed city James Richard Smart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Smart, James Richard, "Rhetorical and narrative structures in John Hersey's Hiroshima: How they breathe life into the tale of a doomed city" (2004). Theses Digitization Project. 2718. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2718 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RHETORICAL AND NARRATIVE STRUCTURES IN JOHN HERSEY'S HIROSHIMA: HOW THEY BREATHE LIFE INTO THE TALE OF A DOOMED CITY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition: English Literature by James Richard Smart June 2004 RHETORICAL AND NARRATIVE STRUCTURES IN JOHN HERSEY'S HIROSHIMA: HOW THEY BREATHE LIFE INTO THE TALE OF A DOOMED CITY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by James Richard Smart June 2004 Approved by: xflUAJg Bruce Golden, Chair, English Date Ellen Gil-Gomez, English'^ Risa> Dickson, Communication Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.................................................. iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION................................ 1 CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND ON HERSEY AND HIROSHIMA....... -

Stoff, Department of History

Course Number: TC 302 Title: The Atomic Bomb in History, Film and Literature Instructor: Professor Michael B. Stoff, Department of History BRIEF COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will examine the Development anD use of the atomic bombs on Japan. Employing a variety of primary sources both written and visual, we will explore the two weapons from historical, cinematic anD literary perspectives as well as from American anD Japanese vantage w in the years before, during and after the Second World War. CONTENT The course seeKs to explain why anD how the atomic bombs were inventeD, how and why they were used, and what the consequences of their use were for the worlD at large. We will looK at both the bombers anD the bombeD anD investigate how atomic weapons transformeD the lives of those who employeD them anD those against whom they were employeD. No event in the twentieth century haD a greater impact on the course of human history than what is now regarDeD as the worlD's first nuclear war. AnD in the twenty-first century, no even is more salient. CORE OBJECTIVES StuDents will be asKeD to examine anD interpret a variety of materials, incluDing archival Documents, feature films, anD novels/narrative non-fiction that Deal with the use anD consequences of the atomic bombs at the end of the SeconD WorlD War. These sources will be DeriveD from both American anD Japanese materials. StuDents will be asKeD to compare anD contrast these perspectives in weeKly Discussions, in short papers anD in classroom Debate. Students will also be askeD to draw conclusions in several short, written exercises throughout the semester anD one longer assignment at the enD of it. -

John F. Kennedy: Public Perception and Campaign Strategy in 1946 By

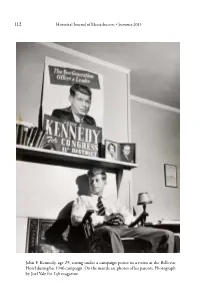

112 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2013 John F. Kennedy, age 29, sitting under a campaign poster in a room at the Bellevue Hotel during his 1946 campaign. On the mantle are photos of his parents. Photograph by Joel Yale for Life magazine. 113 John F. Kennedy: Public Perception and Campaign Strategy in 1946 SETH M. RIDINGER Editor’s Introduction: Boston politics in the 1940s were replete with backroom dealmaking, cigar smoke, and corruption; it was a world of insiders. In 1946, John F. Kennedy took on this hostile realm in a bid for the United States Congress. Kennedy’s victory set his trajectory firmly on the path toward the White House. However, it was not Kennedy’s unlimited coffers that propelled him into office; instead, it was his ability to shape public perception and outwork the other candidates, his innovations in campaign strategy, and his appeal as a naval war hero that swept him to electoral victory. The author argues that although money is an important factor in politics, it was not the determining factor in Kennedy’s 1946 success. The author’s research draws on the extensive oral history collections of the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum. The Oral History Program’s goal is to “collect, preserve, and make available interviews conducted with individuals who were in some way associated with John F. Kennedy and his legacy.” The collection comprises more than 1,700 interviews; interviewees include prominent public figures as well as private individuals who played distinct roles in Kennedy’s life, career, Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. -

The Special Characteristics of John Hersey's Writing

THE SPECIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF JOHN HERSEY’S WRITING STYLE IN HIROSHIMA AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By JUVENTUS GEMBONG NUSANTARA Student Number: 054214021 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 THE SPECIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF JOHN HERSEY’S WRITING STYLE IN HIROSHIMA AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By JUVENTUS GEMBONG NUSANTARA Student Number: 054214021 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 i Others have seen what is and asked why. I have seen what could be and asked why not. ‐ Pablo Picasso In a war, a normal code of social life was suspended. - James Nachtwey For or less, I’m free. - Gembong Nusantara FOR THE REST OF MY SOLITARY LIFE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The first one, I would like to thank the Almighty God for being inside me. Thanks for the love and blessing upon me. I believe without the Almighty God’s hand I will not have any power to finish this thesis. I do love the Almighty God with my whole heart and soul. I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A. for helping me in finishing this thesis. I thank for the patience, guidance, advice, time, and support. This thesis would not complete without his help. I would like to thank my co-advisor, J. Harris H.