Prabagaran A/L Srivijayan V Public Prosecutor and Other Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[2020] SGCA 16 Civil Appeal No 99 of 2019 Between Wham Kwok Han](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5871/2020-sgca-16-civil-appeal-no-99-of-2019-between-wham-kwok-han-155871.webp)

[2020] SGCA 16 Civil Appeal No 99 of 2019 Between Wham Kwok Han

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2020] SGCA 16 Civil Appeal No 99 of 2019 Between Wham Kwok Han Jolovan … Appellant And The Attorney-General … Respondent Civil Appeal No 108 of 2019 Between Tan Liang Joo John … Appellant And The Attorney-General … Respondent Civil Appeal No 109 of 2019 Between The Attorney-General … Appellant And Wham Kwok Han Jolovan … Respondent Civil Appeal No 110 of 2019 Between The Attorney-General … Appellant And Tan Liang Joo John … Respondent In the matter of Originating Summons No 510 of 2018 Between The Attorney-General And Wham Kwok Han Jolovan In the matter of Originating Summons No 537 of 2018 Between The Attorney-General And Tan Liang Joo John ii JUDGMENT [Contempt of Court] — [Scandalising the court] [Contempt of Court] — [Sentencing] iii This judgment is subject to final editorial corrections approved by the court and/or redaction pursuant to the publisher’s duty in compliance with the law, for publication in LawNet and/or the Singapore Law Reports. Wham Kwok Han Jolovan v Attorney-General and other appeals [2020] SGCA 16 Court of Appeal — Civil Appeals Nos 99, 108, 109 and 110 of 2019 Sundaresh Menon CJ, Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA, Judith Prakash JA, Tay Yong Kwang JA and Steven Chong JA 22 January 2020 16 March 2020 Judgment reserved. Sundaresh Menon CJ (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 These appeals arise out of HC/OS 510/2018 (“OS 510”) and HC/OS 537/2018 (“OS 537”), which were initiated by the Attorney-General (“the AG”) to punish Mr Wham Kwok Han Jolovan (“Wham”) and Mr Tan Liang Joo John (“Tan”) respectively for contempt by scandalising the court (“scandalising contempt”) under s 3(1)(a) of the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act 2016 (Act 19 of 2016) (“the AJPA”). -

Ramesh S/O Krishnan V AXA Life Insurance Singapore Pte Ltd

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2016] SGCA 47 Civil Appeal No 112 of 2015 Between RAMESH S/O KRISHNAN … Appellant And AXA LIFE INSURANCE SINGAPORE PTE LTD … Respondent In the matter of Suit No 1022 of 2012 Between RAMESH S/O KRISHNAN … Plaintiff And AXA LIFE INSURANCE SINGAPORE PTE LTD … Defendant JUDGMENT [Tort]—[Negligence]—[Breach of duty] [Tort]—[Negligence]—[Causation] This judgment is subject to final editorial corrections approved by the court and/or redaction pursuant to the publisher’s duty in compliance with the law, for publication in LawNet and/or the Singapore Law Reports. Ramesh s/o Krishnan v AXA Life Insurance Singapore Pte Ltd [2016] SGCA 47 Court of Appeal — Civil Appeal No 112 of 2015 Sundaresh Menon CJ, Chao Hick Tin JA and Steven Chong J 25 November 2015 27 July 2016 Judgment reserved. Sundaresh Menon CJ (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 Employers often require potential hirees to provide references from their former employers. Such references may serve as a basis for the prospective employer to assess the applicant’s character and abilities, and will likely have at least some, if not significant, bearing on the applicant’s chances of obtaining employment. For this and other reasons, which we will elaborate upon in the course of this judgment, it is important that employers prepare such references, when called upon to do so, in a fair and accurate manner to avoid unjustifiably prejudicing the former employee’s prospects of obtaining fresh employment. Before us, it was accepted that an employer has a duty of care when preparing such a reference. -

331KB***Administrative and Constitutional

(2016) 17 SAL Ann Rev Administrative and Constitutional Law 1 1. ADMINISTRATIVE AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW THIO Li-ann BA (Oxon) (Hons), LLM (Harvard), PhD (Cantab); Barrister (Gray’s Inn, UK); Provost Chair Professor, Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore. Introduction 1.1 In terms of administrative law, the decided cases showed some insight into the role of courts in relation to: handing over town council management to another political party after a general election, the susceptibility of professional bodies which are vested with statutory powers like the Law Society review committee to judicial review; as well as important observations on substantive legitimate expectations and developments in exceptions to the rule against bias on the basis of necessity, and how this may apply to private as opposed to statutory bodies. Many of the other cases affirmed existing principles of administrative legality and the need for an evidential basis to sustain an argument. For example, a bare allegation of bias without evidence cannot be sustained; allegations of bias cannot arise when a litigant is simply made to follow well-established court procedures.1 1.2 Most constitutional law cases revolved around Art 9 issues. Judicial observations on the nature or scope of specific constitutional powers were made in cases not dealing directly with constitutional arguments. See Kee Oon JC in Karthigeyan M Kailasam v Public Prosecutor2 noted the operation of a presumption of legality and good faith in relation to acts of public officials; the Prosecution, in particular, is presumed “to act in the public interest at all times”, in relation to all prosecuted cases from the first instance to appellate level. -

Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

RESPONSE BY CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2018 Monday, 8 January 2018 Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Members of the Bar, Honoured Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen: I. Introduction 1. It is my pleasure, on behalf of the Judiciary, to welcome you all to the Opening of this Legal Year. I particularly wish to thank the Honourable Chief Justice Prof Dr M Hatta Ali and Justice Takdir Rahmadi of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Indonesia, the Right Honourable Tun Md Raus Sharif, Chief Justice of Malaysia, and our other guests from abroad, who have made the effort to travel here to be with us this morning. II. Felicitations 2. 2017 was a year when we consolidated the ongoing development of the Supreme Court Bench, and I shall begin my response with a brief recap of the major changes, most of which have been alluded to. 1 A. Court of Appeal 3. Justice Steven Chong was appointed as a Judge of Appeal on 1 April 2017. This was in anticipation of Justice Chao Hick Tin’s retirement on 27 September 2017, after five illustrious decades in the public service. In the same context, Justice Andrew Phang was appointed Vice-President of the Court of Appeal. While we will feel the void left by Justice Chao’s retirement, I am heartened that we have in place a strong team of judges to lead us forward; and delighted that Justice Chao will continue contributing to the work of the Supreme Court, following his appointment, a few days ago, as a Senior Judge. -

OPENING of the LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General

OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General, Mr Lucien Wong, S.C. 11 January 2021 May it please Your Honours, Chief Justice, Justices of the Court of Appeal, Judges of the Appellate Division, Judges and Judicial Commissioners, Introduction 1. The past year has been an extremely trying one for the country, and no less for my Chambers. It has been a real test of our fortitude, our commitment to defend and advance Singapore’s interests, and our ability to adapt to unforeseen difficulties brought about by the COVID-19 virus. I am very proud of the good work my Chambers has done over the past year, which I will share with you in the course of my speech. I also acknowledge that the past year has shown that we have some room to grow and improve. I will outline the measures we have undertaken as an institution to address issues which we faced and ensure that we meet the highest standards of excellence, fairness and integrity in the years to come. 2. My speech this morning is in three parts. First, I will talk about the critical legal support which we provided to the Government throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Second, I will discuss some initiatives we have embarked on to future-proof the organisation and to deal with the challenges which we faced this past year, including digitalisation and workforce changes. Finally, I will share my reflections about the role we play in the criminal justice system and what I consider to be our grave and solemn duty as prosecutors. -

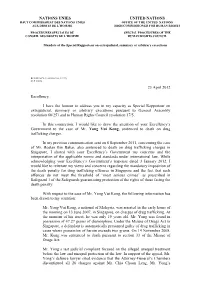

Internal Communication Clearance Form

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT DES NATIONS UNIES OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS AUX DROITS DE L’HOMME HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PROCEDURES SPECIALES DU SPECIAL PROCEDURES OF THE CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L’HOMME HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Mandate of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions REFERENCE: UA G/SO 214 (33-27) SGP 1/2012 23 April 2012 Excellency, I have the honour to address you in my capacity as Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions pursuant to General Assembly resolution 60/251 and to Human Rights Council resolution 17/5. In this connection, I would like to draw the attention of your Excellency‟s Government to the case of Mr. Yong Vui Kong, sentenced to death on drug trafficking charges. In my previous communication sent on 6 September 2011, concerning the case of Mr. Roslan Bin Bakar, also sentenced to death on drug trafficking charges in Singapore, I shared with your Excellency‟s Government my concerns and the interpretation of the applicable norms and standards under international law. While acknowledging your Excellency‟s Government‟s response dated 3 January 2012, I would like to reiterate my views and concerns regarding the mandatory imposition of the death penalty for drug trafficking offences in Singapore and the fact that such offences do not meet the threshold of “most serious crimes” as prescribed in Safeguard 1 of the Safeguards guaranteeing protection of the rights of those facing the death penalty. With respect to the case of Mr. Yong Vui Kong, the following information has been drawn to my attention: Mr. -

Micheal Anak Garing V Public Prosecutor and Another Appeal

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2017] SGCA 07 Criminal Appeal No 9 of 2015 Between MICHEAL ANAK GARING … Appellant And PUBLIC PROSECUTOR … Respondent Criminal Appeal No 11 of 2015 Between PUBLIC PROSECUTOR … Appellant And TONY ANAK IMBA … Respondent In the matter of Criminal Case No 19 of 2013 Between PUBLIC PROSECUTOR And (1) MICHEAL ANAK GARING (2) TONY ANAK IMBA JUDGMENT [Criminal Law]—[Offences]—[Murder] [Criminal Procedure and Sentencing]—[Sentencing]—[Appeals] This judgment is subject to final editorial corrections approved by the court and/or redaction pursuant to the publisher’s duty in compliance with the law, for publication in LawNet and/or the Singapore Law Reports. Micheal Anak Garing v Public Prosecutor and another appeal [2017] SGCA 07 Court of Appeal — Criminal Appeals Nos 9 and 11 of 2015 Chao Hick Tin JA, Andrew Phang Boon Leong JA and Judith Prakash JA 5 September 2016 27 February 2017 Judgment reserved. Chao Hick Tin JA (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 Micheal Anak Garing (“MAG”) and Tony Anak Imba (“TAI”) were both tried in the High Court under s 300(c) of the Penal Code (Cap 224, 2008 Rev Ed) for the murder of one Shanmuganathan Dillidurai (“the deceased”). They were both charged with murder committed in furtherance of a common intention, and were thus liable to be punished under s 302(2) read with s 34 of the Penal Code. 2 MAG and TAI, together with two other friends, Hairee Anak Landak (“HAL”) and Donny Anak Meluda (“DAM”) (collectively, “the Gang”), had set out from a friend’s house on the night of 29 May 2010 with a preconceived plan to commit robbery. -

Internal Communication Clearance Form

HAUT-COMMISSARIAT AUX DROITS DE L’HOMME • OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions and the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment REFERENCE: UA SGP 3/2015: 30 October 2015 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacity as Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions and Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 26/12 and 25/13. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning the imminent execution of Mr. Kho Jabing, a Malaysian national sentenced to death for murder by a Singaporean court. According to the information received: On 30 July 2010, Mr. Kho Jabing, a Malaysian national and a co-defendant were convicted of murder in Singapore after a 2008 robbery resulting in death. As the capital punishment was mandatory for murder until 2012, they were sentenced to death. On 24 May 2011, Mr. Jabing’s co-defendant was convicted of “robbery with hurt” while his death sentence was confirmed. In 2012, following a penal reform Singapore reviewed its mandatory capital punishment laws. The courts were allowed to impose either the death penalty or other sanctions including life imprisonment for drug trafficking and murder. On 30 April 2013, the Court of Appeal decided to re-sentence Mr. Jabing, arguing that his case meets the requirements of the definition of murder under Section 300(c) of the Penal Code, stating that when there is no intention to cause death judges have the option to impose either the death penalty or life imprisonment or caning. -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

The Janus-Faced State: an Obstacle to Human Rights Lawyering in Post-Colonial Asia-Pacific

Title: THE JANUS-FACED STATE: AN OBSTACLE TO HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYERING IN POST-COLONIAL ASIA-PACIFIC Author: Shreyas NARLA Uploaded: 20 September 2019 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of LAWASIA or its members. THE JANUS-FACED STATE: AN OBSTACLE TO HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYERING IN POST-COLONIAL ASIA-PACIFIC† Shreyas Narla* Human rights lawyers now constitute an emergent vulnerable class. This is largely on account of the various causes they represent which pits them in opposition to forces of oppression. Such a fault-line and the consequent fallouts can be traced to the historicity and prevalent patterns of governance and administration in a given State, particularly in the postcolonial states of the Asia Pacific. These states, with their shared colonial histories and legacies, have had many conflicting interests to balance and remedy, and yet are confronted with the realities of their multiple stories of oppression and human rights violations of the lawyers challenging them. Human rights lawyers belonging to these states assume a special role and responsibility as they endure much risk in order to course-correct such actions. While non- state actors and private citizens can be brought to book for violations under prevalent laws, the complexity lies where the State itself is the oppressor instead of being the facilitator. The legal impunity that guards such State- sponsored oppression plays a severe deterrent to their lawyering and requires attention, both in terms of data analyses and reformative policy. I. INTRODUCTION The modern State, meant to be a benign protector of the rights of its citizens, is also the harshest oppressor that uses several instrumentalities at its disposal to control and regulate their actions. -

SAL Annual Report 2017

An nu al R ep or t 2017/18 ears of Sharing and Creating Value The SAL Story 03 An interview with The President 06 SAL 30th Anniversary Celebration 08 SAL Senate 10 SAL Executive Board 12 SAL Key Executives 14 Organisational Structure 15 Key Statistics 16 Setting new precedents for Singapore Law 17 Financial Statements 35 SAL ANNUAL THE 02 REPORT 2017/18 SAL STORY 03 THE SAL STORY The Singapore Academy of Law Bill was Our Vision passed in 1988. It was said to be a giant step forward; lawyers will have a forum Singapore — for sharing ideas, SAL will not only help to promote a sense of belonging amongst The Legal hub of Asia members of the legal profession, but also raise the standard of legal services in Singapore. At least 1,700 people were Our Mission expected to be members, including judges, practising lawyers, legal service officers, Driving legal excellence lecturers in the university’s law faculty and law students. through thought leadership, Modelled after the Inns of Court in London, SAL provided dining facilities world-class infrastructure in City Hall to enable the Chief Justice and judges to get together over lunches and solutions and dinners with members of the legal fraternity for closer rapport. At the first Senate meeting held on 19 January 1989, with the late CJ Wee Chong Jin as President, eight Committees were appointed to carry out the functions of SAL. None had full-time staff. It was nevertheless a promising start. The first issue of the Singapore Academy of Law Journal was published in December 1989 and in the following year, SAL organised its first major conference to discuss “Legal Services in the 1990s”. -

Ho Kang Peng V Scintronix Corp

Ho Kang Peng v Scintronix Corp Ltd (formerly known as TTL Holdings Ltd) [2014] SGCA 22 Case Number : Civil Appeal No 24 of 2013 Decision Date : 30 April 2014 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Sundaresh Menon CJ; Chao Hick Tin JA; V K Rajah JA Counsel Name(s) : Alvin Tan Kheng Ann (Wong Thomas & Leong) for the Appellant; Tony Yeo and Fong King Man (Drew & Napier LLC) for the Respondent. Parties : Ho Kang Peng — Scintronix Corp Ltd (formerly known as TTL Holdings Ltd) Companies – Directors – Breach of duty [LawNet Editorial Note: The decision from which this appeal arose is reported at [2013] 2 SLR 633.] 30 April 2014 Judgment reserved Chao Hick Tin JA (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 This appeal arises from the decision of the High Court in Suit No 207 of 2009 (“the Suit”). The appellant, Ho Kang Peng (“the Appellant”), who at the relevant time was the chief executive officer (“CEO”) and a director of the respondent, TTL Holdings Limited (“the Company”), was found liable for the breach of various fiduciary duties owed to the Company. The liability arose from certain payments made by the Company to a third party which the High Court found to be unauthorised. The key issues in this appeal concern the purpose for which the payments were made, whether they were duly sanctioned by the Company, and whether the Company is precluded from claiming against the Appellant because it was allegedly equally at fault. Facts Parties to the dispute 2 The Company is a publicly listed company on the Stock Exchange of Singapore (“SGX”) and is engaged in the manufacture and supply of moulds and finished plastic components.