Opens on a Singularly Apologetic Note: "I About the World in Which He Lived

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week Ending 12Th February 2010

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 06 Week Ending: 12th February 2010 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 10/00166/FULLN Erection of two replacement 33 And 34 Andover Road, Red Mr & Mrs S Brown Jnr Mrs Lucy Miranda YES 08.02.2010 dwellings together with Post Bridge, Andover, And Mr R Brown Page ABBOTTS ANN garaging and replacement Hampshire SP11 8BU 12.03.2010 and resiting of entrance gates 10/00248/VARN Variation of condition 21 of 11 Elder Crescent, Andover, Mr David Harman Miss Sarah Barter 10.02.2010 TVN.06928 - To allow garage Hampshire, SP10 3XY 05.03.2010 ABBOTTS ANN to be used for storage room -

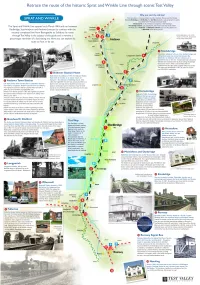

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

The Sacred Books of the East

r-He weLL read mason li""-I:~I=-•I cl••'ILei,=:-,•• Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Planning Services

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 47 Week Ending: 23rd November 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 18/03025/TREEN Fell Fir Tree encroaching on Pollyanna, Little Ann Road, Mr Patrick Roberts Mr Rory Gogan YES 19.11.2018 Cherry tree; T1 Ash and T2 Little Ann, Andover Hampshire 21.12.2018 ABBOTTS ANN Ash both showing signs of SP11 7SN desease and some dieback (see full description on form) 18/03018/FULLN Change of use from Telford Gate, Unit 1 , Mr Ricky Sumner, RSV Mr Luke Benjamin 19.11.2018 factory/warehouse to general Hopkinson Way, Portway Services 12.12.2018 ANDOVER TOWN industrial to include vehicle Business Park, Andover SP10 (HARROWAY) repairs and servicing and 3SF MOT testing 18/03067/CLEN -

King's Somborne Footpath Walks 2014

King’s Somborne Footpath Walks 2014 The programme of footpath walks listed below is as of 1 January 2014 and may be subject to change throughout the year. Please refer to the village website (www.thesombornes.org.uk – Directory – Footpath Walk) for the latest information. Sunday 26 January 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 5½ miles (8¾ Km) 2¼ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and up Red Hill before turning onto the path past Ashley New buildings. At the crossroads we take the path across the field past Ashley Manor Farm and then over the hill to Chalk Vale before returning to the village past the beef unit and back along Winchester Road. Sunday 23 February 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 4¾ miles (7½ Km) 2 hours We cross Palace Field and alongside the churchyard to pick up the Clarendon Way alongside Cow Drove Hill. We follow the Clarendon Way past How Park and across the water meadows to Houghton. From Houghton, it is road walking past the site of Bossington village before taking the footpath along the line of the Roman road to Horsebridge and the footpath back to the village. Sunday 30 March 2014 2:00 pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 6 miles (9½ Km) 2½ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and take the path past the Beef Unit. We continue towards Up Somborne before turning left to take the steep path down to Little Somborne. At Little Somborne we head North to North Park Farm and the path back towards the village. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

2021 01 Jan 11Th Planning Agenda

KING’S SOMBORNE PARISH COUNCIL All Members of the Planning Committee are summonsed to attend a virtual meeting, via Zoom, on Monday 11th January 2021 at 6.30pm Zoom Link & Codes: Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/86707740778?pwd=azdLM1dVZm5VOGNBazJXYTEwKzVFdz09 Meeting ID: 867 0774 0778 Passcode: 362474 One tap mobile: 02034815237 This Meeting is held in Public. Members of the public are welcome to attend & speak in the public session. AGENDA 1. Welcome and Introduction 2. Comments from the floor 3. Apologies for absence 4. To resolve as accurate the minutes of the Planning Committee meeting held 7th December 2020 5. Declarations of Interest 6. Consideration of Planning Applications a. Lawful Development Certificate for existing uses - Area A, timber yard for production, storage and distribution of timber products; Area B, mixed use of asphalt plant and storage/distribution use; Area C, offices Land At How Park Farm Cow Drove Hill Kings Somborne SO20 6QG Ref. No: 20/03235/CLES | Standard Consultation Expiry Date: Tuesday 19th January 2021 |Parish Council Consultation Expiry Date: Wednesday 20th January 2021 b. New barn doors and roof to barn Marsh Court Farm Romsey Road Stockbridge SO20 6DF Ref. No: 20/03212/LBWS | Standard Consultation Expiry Date: Monday 18th January 2021|Parish Council Consultation Expiry Date: Friday 22nd January 2021 c. Erection of pitched roof front porch, replacement single storey rear extension to accommodate an open plan kitchen/dining/living space, pitched roof to existing first floor dormer window and existing ground floor bay windows, amendment of 3 windows Woodlings Winchester Road Kings Somborne SO20 6NZ Ref. -

Hampshire Minerals and Waste Plan (Draft - for Cabinet) July 2013

H A M P S H I R E PORTSMOUTH, SOUTHAMPTON, NEW FOREST & SOUTH DOWNS MINERALS AND WASTE PLAN Draft for consideration by the partner authorities at democratic meetings (July 2013) All Plans reproduced within this document meet copyright of the data suppliers Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationary Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution of civil proceedings. HCC 100019180 2012. © Environment Agency Copyright 2012. All rights reserved. Reproduced from the British Geological Survey Map data at the original scale of 1:100,000. Licence 2008/202 British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Hampshire Minerals and Waste Plan (Draft - for Cabinet) July 2013 Foreword 4 1 Introduction 6 2 Vision and Spatial Strategy 9 Hampshire in 2011 10 Issues for the Plan 14 Other Plans and Programmes 15 Vision - Where we need to be 16 Spatial Strategy 17 Key Diagram 21 3 Sustainable minerals and waste development 23 4 Protecting Hampshire's Environment 26 Climate change 28 Habitats and species 29 Landscape and countryside 32 South West Hampshire Green Belt 35 Heritage 37 Soils 38 Restoration of quarries and waste developments 40 5 Maintaining Hampshire's Communities 45 Protecting public health, safety and amenity 46 Flooding - risk and prevention 48 Managing traffic impacts 49 Design, construction and operation of minerals and waste development 51 CommunityDRAFT benefits 53 6 Supporting Hampshire's Economy 55 Safeguarding mineral resources 57 Safeguarding -

Resourceful Disciple

RESOURCEFUL DISCIPLE the LIFE, TIMES, & EXTENDED FAMILY of THOMAS EDWARDS BASSETT (1862-1926) by Arthur R. Bassett Prologue Purposed Audience and Prepared Authorship Part 1: For Whom the Bells Toll: Three Target Audiences It might be argued that every written composition, either by intent or subconsciously, has an intended audience to whom it is addressed; this biography, as indicated in the title, has three: 1) those interested in the facts surrounding the life of Thomas E. Bassett, 2) those interested in his times, and 3) those with an interest in his extended family. 1) Those Interested in His Life In one sense, this is the story of a single solitary life, selected and plucked from a pool of billions. It is the life of Thomas E. Bassett. He is not only my grandfather; he is also one of my heroes, so I hope that I can be forgiven if at times this biography exhibits overtones of a hagiography.1 I feel that his story deserves to be preserved, if for no other reason than his life was so extraordinary. It is truly a classic example of the America dream come true. Like most of his immediate descendants, I had heard the litany of his achievements from my very early childhood: first state senator from his county, first schoolteacher in Rexburg, first postmaster, newspaper editor, stake president, etc. However, as far as I know, no one has laid out the entire tapestry of his life in such a way that the chronological order and interrelationship of these accomplishments is demonstrated. This has been a major part of my project in this biography. -

Week Ending 5Th June 2015

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 23 Week Ending: 5th June 2015 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 15/01158/ADVN Display of 3 non-illuminated 280 Weyhill Road, Andover, Mr D Wolfenden Mr Oliver Woolf YES 01.06.2015 fascia signs on new building Hampshire, SP10 3LS 25.06.2015 ANDOVER TOWN (HARROWAY) 15/01186/ADVN Installation of three internally Andover Trade Park, Joule Mole Valley Farmers Mrs Sharon YES 02.06.2015 illuminated fascia signs Road, Portway Business Park, Ltd Brentnall ANDOVER TOWN Andover, SP10 3ZL 29.06.2015 (HARROWAY) 15/01273/TPON 1 x Lime - Prune 3m off 1 Keeble Place, The Drove, Graham Bartlett Miss Rachel Cooke 01.06.2015 height and 1.5m off width. 1x Andover, Hampshire SP10 3PA 23.06.2015 -

Ilíl 11II Que Quer Qucj Pe*Io.S Actos Ma.Js Reprováveis, Foi Tradições Do Sempre* Contestação Do Sr

r-7^ -í æ'*¦?- .i-? *:'•¦ ** 'íí^"- * æ"* ** ¦:*¦ - t'"''^ ¦ -r— SEDE SOCIAL ASSIGNATURA NA Doze -mezes. 30|ooo Avenida Rio Branco Seis mezes . i6$ooo - 128, 130, 132 Um mez . 3$ooo . í NUMERO AVULSO 100 us. *\«' ' " ' ' '-! t JM. "3^ \jp - "¦!'" ANNO — N? 10.072 Jornal Indopeiiclonto. .k XXVIÜ RIO ÜE JANEIRO, SABBADO, 4 DE DE político, MAIO 1912 litoi-urlo e noticioso do rosto do cujas rugas n. pressão pai, aos mais exaltados luctadores daquel- disciplina, a esse desvio da» attribui- tarde, ouvir a continuação da farto. Factos e obra é que todos recla- guida que representa o sentimento da opi- da fronte revelam uma idéa tenaz, *a para respeitável legião- O governo é ções militares, a esse rebaixamento, réplica do Sr. Severino Vieira á toam. nião nacional, no protesto contra o reco- uma idéa elle fazer trium-' das exercito, nhecimento Ilíl 11II que quer quCj pe*io.s actos ma.js reprováveis, foi tradições do sempre* contestação do Sr. Luiz Vianna. Esse tardio movimento em defesa da traudulento do Sr. Raymíindi e triumpho escolhe a 1 phar, para cujo descendo, dia a dia, na confiança do obediente á lei e collaborador leaPda* Federação não passa de film. sem valor, de Miranda, como o fez no seio da carne de sua carne, um com- própria pe-('povo, e, entre elles, destaca-se o de grandeza* do regimen.'. Caso haja- numero, o Senado ele- de <]ue, .para aos atirarem poeira aos olhos, missão, porque essa'é a expressão rcil da .. .1 will speak as liberal daço do seu próprio coração monstruosos fuzilamentos do Satelli- Aprazia-lhe o despertar dessas agi- lançam mão os freis Thomazes da política verdade. -

Esconet Text Retrieval System

EscoNet Text Retrieval System TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL - PLANNING SERVICES WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 40 Week Ending: Friday, 1 October 2004 Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING to arrive before the expiry date shown in the last column For the Northern Area (TVN) to: For the Southern Area (TVS) to Head of Planning Head of Planning Council Offices 'Beech Hurst' Duttons Road Weyhill Road ROMSEY SO51 8XG ANDOVER SPIO 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection PLANNING APPLICATIONS APPLICATION NO. / PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER / REGISTRATION DATE PUBLICITY EXPIRY DATE http://www.minutes.org.uk/cgi-bin/cgi003.exe?Y,,,00000000000000100000...,,01.10.04,14223067,14295901,1,011004.HTM,1,1,1,P,67798058,0,00,00,N (1 of 6) [06/06/2013 17:03:40] EscoNet Text Retrieval System TVN.09223 Erection of rear conservatory 3 Elder Crescent, ABBOTTS ANN Mr S Grainger Maggie Francis 28.09.2004 Ms K M Auton 26.10.2004 TVN.09242 Erection of conservatory to rear 1 Stone Close, Andover Mr And Mrs Woodward Paul Goodman 28.09.2004 MILLWAY 26.10.2004 TVN.08963/1 Erection of two storey extension to 16 The Avenue, Andover Mr G Kitchen William Josey 28.09.2004 provide conservatory and garage MILLWAY Miss J Sellwood 26.10.2004 with bedroom and en-suite over TPO.00832/11 Gradual removal of whole conifer Tillers, Barncroft, APPLESHAW Mr And Mrs C & S Jones Dermot Cox 27.09.2004 hedge over a period of five years 26.10.2004 TVN.LB.00084/6 Installation of architectural lighting The Guildhall, High Street, Urban Projects Limited William Josey 27.09.2004 scheme Andover ST MARY'S 29.10.2004 TRE.CA.00587/97 Cotoneaster tree - Shorten back Fleur De Lys, AMPORT Andrew Douglas 27.09.2004 some branches on house side by one 26.10.2004 third.