Digital Signal Processing in Clinical Validation Studies with Impedance Plethysmography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signal and Image Processing in Biomedical Photoacoustic Imaging: a Review

Review Signal and Image Processing in Biomedical Photoacoustic Imaging: A Review Rayyan Manwar 1,*,†, Mohsin Zafar 2,† and Qiuyun Xu 2 1 Richard and Loan Hill Department of Bioengineering, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60607, USA 2 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48201, USA; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (Q.X.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors have equal contributions. Abstract: Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a powerful imaging modality that relies on the PA effect. PAI works on the principle of electromagnetic energy absorption by the exogenous contrast agents and/or endogenous molecules present in the biological tissue, consequently generating ultrasound waves. PAI combines a high optical contrast with a high acoustic spatiotemporal resolution, al- lowing the non-invasive visualization of absorbers in deep structures. However, due to the optical diffusion and ultrasound attenuation in heterogeneous turbid biological tissue, the quality of the PA images deteriorates. Therefore, signal and image-processing techniques are imperative in PAI to provide high-quality images with detailed structural and functional information in deep tissues. Here, we review various signal and image processing techniques that have been developed/implemented in PAI. Our goal is to highlight the importance of image computing in photoacoustic imaging. Keywords: photoacoustic; signal enhancement; image processing; SNR; deep learning 1. Introduction Citation: Manwar, R.; Zafar, M.; Xu, Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a non-ionizing and non-invasive hybrid imaging Q. Signal and Image Processing in modality that has made significant progress in recent years, up to a point where clinical Biomedical Photoacoustic Imaging: studies are becoming a real possibility [1–6]. -

Digital Camera Identification Using Sensor Pattern Noise for Forensics Applications

Citation: Lawgaly, Ashref (2017) Digital camera identification using sensor pattern noise for forensics applications. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/32314/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html DIGITAL CAMERA IDENTIFICATION USING SENSOR PATTERN NOISE FOR FORENSICS APPLICATIONS Ashref Lawgaly A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Engineering and Environment January 2017 DECLARATION I declare that no outputs submitted for this degree have been submitted for a research degree of any other institution. I also confirm that this work fully acknowledges opinions, ideas and contributions from the work of others. Any ethical clearance for the research presented in this commentary has been approved. -

Understanding Digital Signal Processing

Understanding Digital Signal Processing Richard G. Lyons PRENTICE HALL PTR PRENTICE HALL Professional Technical Reference Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458 www.photr,com Contents Preface xi 1 DISCRETE SEQUENCES AND SYSTEMS 1 1.1 Discrete Sequences and Their Notation 2 1.2 Signal Amplitude, Magnitude, Power 8 1.3 Signal Processing Operational Symbols 9 1.4 Introduction to Discrete Linear Time-Invariant Systems 12 1.5 Discrete Linear Systems 12 1.6 Time-Invariant Systems 17 1.7 The Commutative Property of Linear Time-Invariant Systems 18 1.8 Analyzing Linear Time-Invariant Systems 19 2 PERIODIC SAMPLING 21 2.1 Aliasing: Signal Ambiquity in the Frequency Domain 21 2.2 Sampling Low-Pass Signals 26 2.3 Sampling Bandpass Signals 30 2.4 Spectral Inversion in Bandpass Sampling 39 3 THE DISCRETE FOURIER TRANSFORM 45 3.1 Understanding the DFT Equation 46 3.2 DFT Symmetry 58 v vi Contents 3.3 DFT Linearity 60 3.4 DFT Magnitudes 61 3.5 DFT Frequency Axis 62 3.6 DFT Shifting Theorem 63 3.7 Inverse DFT 65 3.8 DFT Leakage 66 3.9 Windows 74 3.10 DFT Scalloping Loss 82 3.11 DFT Resolution, Zero Padding, and Frequency-Domain Sampling 83 3.12 DFT Processing Gain 88 3.13 The DFT of Rectangular Functions 91 3.14 The DFT Frequency Response to a Complex Input 112 3.15 The DFT Frequency Response to a Real Cosine Input 116 3.16 The DFT Single-Bin Frequency Response to a Real Cosine Input 117 3.17 Interpreting the DFT 120 4 THE FAST FOURIER TRANSFORM 125 4.1 Relationship of the FFT to the DFT 126 4.2 Hints an Using FFTs in Practice 127 4.3 FFT Software Programs -

Averaging Correlation for Weak Global Positioning System Signal Processing

AVERAGING CORRELATION FOR WEAK GLOBAL POSITIONING SYSTEM SIGNAL PROCESSING A Thesis Presented to The Faculty ofthe Fritz J. and Dolores H. Russ College ofEngineering and Technology Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master ofScience by ZhenZhu June, 2002 OHIO UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank all the people who had helped me on my research all through the past years. Particularly I would like to acknowledge some of them who did directly support me on this thesis. First I would express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Starzyk. It is him who first led me into the area of GPS. He offered insight directions to all my research topics. His professional advices always inspired me. I would like to thank Dr. van Graas for his guidance, patience and encouragements. His effort is very important to my research. Also Dr. Uijt de Haag must be specially thanked for being my committee member. Sincere thanks are for Dr. Matolak. From his courses about mobile communication, I did learn a lot that I had never been taught in other classes. The assistance provided by all the faculty members in the EECS School will never be forgotten. This thesis would never be finished without the help ofmy friends, especially Jing Pang, Abdul Alaqeeli and Sanjeev Gunawardena. Their cooperation made it possible for me to complete my research quickly. Finally, the support from my family gives me the opportunity to study here. All my energy to work on my research is from them. IV TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES vi LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 GLOBAL POSITIONING SySTEM 4 3 GPS SIGNAL PROCESSING 7 3.1 GPS Signal Structure 7 3.2 GPS Receiver Architecture 12 3.3 GPS Signal Processing- Acquisition 14 3.3.1 Acquisition 14 3.3.2 Signal Power and Misdetection Probability 16 3.3.3 Demodulating Frequency 24 3.4 Tracking 25 3.4.1 Sequential Time Domain Tracking Loop 25 3.4.2 Correlation Based Tracking 28 3.5 Software Radio Introductions 30 3.6 Hardware Implementations 32 4 AVERAGING 33 4.1 Averaging Up Sampled Signa1. -

Digitisation and Data Processing in Fourier Transform Nmr

0079 6565/X0/0301 0027SO5.00/0 DIGITISATION AND DATA PROCESSING IN FOURIER TRANSFORM NMR J. C. LINDON and A. G. FERRIG~ Department of Physical Chemistry, Wellcome Research Laboratories, Langley Court, Beckenham, Kent BR3 3BS, 1J.K. (Received 17 December 1979) CONTENTS 1. Introduction 28 1,I. Aims of the Review 28 1.2. FTNMR Computer Systems 28 2. Digitisation 29 2.1 Signal-to-Noise 29 2.1.1. Signal averaging 29 2.1.2. Signal-to-noise in time and frequency domains 30 2.2. Hardware Requirements 30 2.2.1. Sample-and-hold 30 2.2.2. Analog-to-digital conversion 31 2.2.3. ADC resolution and error sources 32 2.3. Sampling Rates and Timing 33 2.4. Quantisation Errors 33 2.5. Signal Overflow 34 2.5.1. Introduction 34 2.5.2. Possible number of scans 34 2.5.3. Scaling of memory and ADC 35 2.5.4. Normalised averaging 36 2.5.5. Double length averaging 31 2.6. Signal Averaging in the Presence of Large Signals 37 2.6.1. Number of scans and ADC resolution 37 2.6.2. Spectroscopic methods of improving dynamic range 40 2.6.3. Block averaging 40 2.6.4. Double length averaging 41 2.7 Summary of Averaging Methods 42 3. Manipulations Prior to Fourier Transformation 43 3.1. Zero Filling 43 3.2 Sensitivity Enhancement 45 3.2.1. Introduction 45 3.2.2. Apodisation methods 45 3.3. Resolution Enhancement 47 3.3.1. Introduction and spectroscopic methods 47 3.3.2. -

Introduction Simulation of Signal Averaging

Signal Processing Naureen Ghani December 9, 2017 Introduction Signal processing is used to enhance signal components in noisy measurements. It is especially important in analyzing time-series data in neuroscience. Applications of signal processing include data compression and predictive algorithms. Data analysis techniques are often subdivided into operations in the spatial domain and frequency domain. For one-dimensional time series data, we begin by signal averaging in the spatial domain. Signal averaging is a technique that allows us to uncover small amplitude signals in the noisy data. It makes the following assumptions: 1. Signal and noise are uncorrelated. 2. The timing of the signal is known. 3. A consistent signal component exists when performing repeated measurements. 4. The noise is truly random with zero mean. In reality, all these assumptions may be violated to some degree. This technique is still useful and robust in extracting signals. Simulation of Signal Averaging To simulate signal averaging, we will generate a measurement x that consists of a signal s and a noise component n. This is repeated over N trials. For each digitized trial, the kth sample point in the jth trial can be written as xj(k) = sj(k) + nj(k) Here is the code to simulate signal averaging: % Signal Averaging Simulation % Generate 256 noisy trials trials = 256; noise_trials = randn(256); % Generate sine signal sz = 1:trials; sz = sz/(trials/2); S = sin(2*pi*sz); % Add noise to 256 sine signals for i = 1:trials noise_trials(i,:) = noise_trials(i,:) + S; -

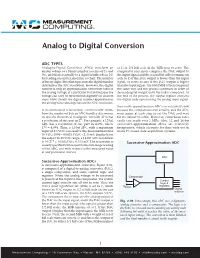

Analog to Digital Conversion

Analog to Digital Conversion ADC TYPES Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADCs) transform an at 1) or 1/4 full scale (if the MSB reset to zero). The analog voltage to a binary number (a series of 1’s and comparator once more compares the DAC output to 0’s), and then eventually to a digital number (base 10) the input signal and the second bit either remains on for reading on a meter, monitor, or chart. The number (sets to 1) if the DAC output is lower than the input of binary digits (bits) that represents the digital number signal, or resets to zero if the DAC output is higher determines the ADC resolution. However, the digital than the input signal. The third MSB is then compared number is only an approximation of the true value of the same way and the process continues in order of the analog voltage at a particular instant because the descending bit weight until the LSB is compared. At voltage can only be represented (digitally) in discrete the end of the process, the output register contains steps. How closely the digital number approximates the digital code representing the analog input signal. the analog value also depends on the ADC resolution. Successive approximation ADCs are relatively slow A mathematical relationship conveniently shows because the comparisons run serially, and the ADC how the number of bits an ADC handles determines must pause at each step to set the DAC and wait its specific theoretical resolution: An n-bit ADC has for its output to settle. However, conversion rates n a resolution of one part in 2 . -

Notes on Noise Reduction

PHYS 331: Junior Physics Laboratory I Notes on Noise Reduction When setting out to make a measurement one often finds that the signal, the quantity we want to see, is masked by noise, which is anything that interferes with seeing the signal. Maximizing the signal and minimizing the effects of noise then become the goals of the experimenter. To reach these goals we must understand the nature of the signal, the possible sources of noise and the possible strategies for extracting the desired quantity from a noisy environment.. Figure 1 shows a very generalized experimental situation. The system could be electrical, mechanical or biological, and includes all important environmental variables such as temperature, pressure or magnetic field. The excitation is what evokes the response we wish to measure. It might be an applied voltage, a light beam or a mechanical vibration, depending on the situation. The system response to the excitation, along with some noise, is converted to a measurable form by a transducer, which may add further noise. The transducer could be something as simple as a mechanical pointer to register deflection, but in modern practice it almost always converts the system response to an electrical signal for recording and analysis. In some experiments it is essential to recover the full time variation of the response, for example the time-dependent fluorescence due to excitation of a chemical reaction with a short laser pulse. It is then necessary to record the transducer output as a function of time, perhaps repetitively, and process the output to extract the signal of interest while minimizing noise contributions. -

Understanding Digital Signal Processing Third Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Understanding Digital Signal Processing Third Edition

Understanding Digital Signal Processing Third Edition This page intentionally left blank Understanding Digital Signal Processing Third Edition Richard G. Lyons Upper Saddle River, NJ • Boston • Indianapolis • San Francisco New York • Toronto • Montreal • London • Munich • Paris • Madrid Capetown • Sydney • Tokyo • Singapore • Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trade- marks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. The author and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied war- ranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or con- sequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The publisher offers excellent discounts on this book when ordered in quantity for bulk purchases or special sales, which may include electronic versions and/or custom covers and content particular to your business, training goals, marketing focus, and branding interests. For more information, please contact: U.S. Corporate and Government Sales (800) 382-3419 [email protected] For sales outside the United States please contact: International Sales [email protected] Visit us on the Web: informit.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lyons, Richard G., 1948- Understanding digital signal processing / Richard G. Lyons.—3rd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-13-702741-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. -

Introduction to Biomedical Engineering

Introduction to Biomedical Engineering Biosignal processing Kung-Bin Sung 1 Outline Chapter 10: Biosignal processing • Characteristics of biosignals • Frequency domain representation and analysis – Fourier series, Fourier transform, discrete Fourier transform – Digital filters • Signal averaging • Time-frequency analysis – Short-time Fourier transform – Wavelet transform • Artificial neural networks 2 Example biosignals EEG EMG Blood pressure ECG 3 Characteristics of (bio)signals • Continuous vs. discrete x(t) continuous variables such as time and space x(n) n =0, 1, 2, 3… ⇒ n is an integer sampled at a finite number of points we will deal with discrete signals in this module (a subset of digital signal processing) • Deterministic vs. random – Deterministic: can be described by mathematical functions or rules Periodic signal is an example of deterministic signals x(t) = x(t + nT ) ⇒ repeats itself every T units in time, T is the period ECG and blood pressure both have dominant periodic components 4 Characteristics of biosignals Random (stochastic) signals - Contain uncertainty in the parameters that describe them, therefore, cannot be precisely described by mathematical functions - Often analyzed using statistical techniques with probability distributions or simple statistical measures such as the mean and standard deviation - Example: EMG (electromyogram) Stationary random signals: the statistics or frequency spectra of the signal remain constant over time. It is the stationary properties of signals that we are interested in Real biological -

Chapter 2: Static and Dynamic Characteristics of Signals

Chapter 2 Static and Dynamic Characteristics of Signals Signals Signals classified as 1. Analog – continuous in time and takes on any magnitude in range of operations 2. Discrete Time – measuring a continuous variable at finite time intervals 3. Digital – discretized magnitude at discrete times Quantization assigns a single number to represent a range of magnitudes of a continuous signal This is done by a Analog to Digital A/D converter 1 Signal Wave Form Static – does not vary with time and can be considered over long periods, like the life of a battery. Dynamic Signal – time dependent y(t) Definitions Deterministic Signal –a signal that varies in time in a predictable manner, such as a sine wave, a step function, or a ramp function. Steady Periodic –a signal whose variation of the magnitude of the signal repeats at regular intervals in time. Definitions cont’d Complex Periodic Waveform – contains multiple frequencies and is represented as a superposition of multiple simple periodic waveforms. Aperiodic Waveforms – deterministic signals that do not repeat at regular intervals (step function). Nondeterministic Signal –a signal with no discernible pattern of repetition. 2 For periodic signal: c = amplitude f = 1/T cycles/sec (hz) T = period ω = 2Πfrad/sec Signal Analysis Assume y=current t 2 t 2 Y = (())/()ytdt dt ∫∫t1 t1 If power is equal to P=I2R, then energy is dissipated in resistor from t1 to t2 Signal Analysis t 2 T 2 E ==Pdt [()]It2 Rdt ∫∫t1 T1 To find a fixed current Ie that produces some energy dissipation in time -

Understanding Digital Signal Processing Third Edition

Understanding Digital Signal Processing Third Edition Richard G. Lyons •• ..•• Pearson Education International Upper Saddle River, NJ • Boston • Indianapolis • San Francisco New York • Toronto • Montreal • London • Munich • Paris • Madrid Capetown • Sydney • Tokyo • Singapore • Mexico City Contents PREFACE xv ABOUT THE AUTHOR xxiii 1 DISCRETE SEQUENCES AND SYSTEMS 1 1.1 Discrete Seguences and Their Notation 2 1.2 Signal Amplitude, Magnitude, Power 8 1.3 Signal Processing Operational Symbols 10 1.4 Introduction to Discrete Linear Time-Invariant Systems 12 1.5 Discrete Linear Systems 12 1.6 Time-Invariant Systems 17 1.7 The Commutative Property of Linear Time-Invariant Systems 18 1.8 Analyzing Linear Time-Invariant Systems 19 References 21 Chapter 1 Problems 23 2 PERIODIC SAMPLING 29 2.1 Aliasing: Signal Ambiguity in the Frequency Domain 29 2.2 Sampling Lowpass Signals 34 2.3 Sampling Bandpass Signals 38 2.4 Practical Aspects of Bandpass Sampling 41 References 45 Chapter 2 Problems 46 3 THE DISCRETE FOURIER TRANSFORM 53 3.1 Understanding the DFT Equation 54 3.2 DFT Symmetry 67 vii viii Contents 3.3 DFT Linearity 69 3.4 DFT Magnitudes 69 3.5 DFT Frequency Axis 71 3.6 DFT Shifting Theorem 71 3.7 Inverse DFT 74 3.8 DFT Leakage 75 3.9 Windows 83 3.10 DFT Scalloping Loss 90 3.11 DFT Resolution, Zero Padding, and Frequency-Domain Sampling 92 3.12 DFT Processing Gain 96 3.13 The DFT of Rectangular Functions 99 3.14 Interpreting the DFT Using the Discrete-Time Fourier Transform 114 References 118 Chapter 3 Problems 119 4 THE FAST FOURIER 'rRANSFORM