The Driftless Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Mississippi River Conservation Opportunity Area Wildlife Action Plan

Version 3 Summer 2012 UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER CONSERVATION OPPORTUNITY AREA WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN Daniel Moorehouse Mississippi River Pool 19 A cooperative, inter-agency partnership for the implementation of the Illinois Wildlife Action Plan in the Upper Mississippi River Conservation Opportunity Area Prepared by: Angella Moorehouse Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Elliot Brinkman Prairie Rivers Network We gratefully acknowledge the Grand Victoria Foundation's financial support for the preparation of this plan. Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. ii Acronym List .............................................................................................................................. iii I. Introduction to Conservation Opportunity Areas ....................................................................1 II. Upper Mississippi River COA ..................................................................................................3 COAs Embedded within Upper Mississippi River COA ..............................................................5 III. Plan Organization .................................................................................................................7 IV. Vision Statement ..................................................................................................................8 V. Climate Change .......................................................................................................................9 -

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV Maps and Descriptions Denis White March 2020

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV maps and descriptions Denis White March 2020 (Image NOAA, Landsat, Copernicus; Presentation Google Earth) A contribution to the corpus of materials created by James Omernik and colleagues on the Ecological Regions of the United States, North America, and South America The page size for this document is 9 inches horizontal by 12 inches vertical. Table of Contents Content Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Geographic patterns in Minnesota 1 Geographic location and notable features 1 Climate 1 Elevation and topographic form, and physiography 2 Geology 2 Soils 3 Presettlement vegetation 3 Land use and land cover 4 Lakes, rivers, and watersheds; water quality 4 Flora and fauna 4 3. Methods of geographic regionalization 5 4. Development of Level IV ecoregions 6 5. Descriptions of Level III and Level IV ecoregions 7 46. Northern Glaciated Plains 8 46e. Tewaukon/BigStone Stagnation Moraine 8 46k. Prairie Coteau 8 46l. Prairie Coteau Escarpment 8 46m. Big Sioux Basin 8 46o. Minnesota River Prairie 9 47. Western Corn Belt Plains 9 47a. Loess Prairies 9 47b. Des Moines Lobe 9 47c. Eastern Iowa and Minnesota Drift Plains 9 47g. Lower St. Croix and Vermillion Valleys 10 48. Lake Agassiz Plain 10 48a. Glacial Lake Agassiz Basin 10 48b. Beach Ridges and Sand Deltas 10 48d. Lake Agassiz Plains 10 49. Northern Minnesota Wetlands 11 49a. Peatlands 11 49b. Forested Lake Plains 11 50. Northern Lakes and Forests 11 50a. Lake Superior Clay Plain 12 50b. Minnesota/Wisconsin Upland Till Plain 12 50m. Mesabi Range 12 50n. Boundary Lakes and Hills 12 50o. -

Pecatonica River: Targeting Conservation Practices in a Watershed to Improve Water Quality

Pecatonica River: Targeting conservation practices in a watershed to improve water quality Madison 151 Partners discuss new stream crossing on the Judd farm. © TNC Pleasant Valley Watershed One of the challenges facing landowners and managers in Wisconsin and nationwide is keeping sediment and phosphorus on the land and out of streams. Too much phosphorus leads to excessive algae growth, which consumes oxygen in the water and can contaminate The group tested this approach in the Pecatonica River drinking water. watershed in southwest Wisconsin, and the results are in. Farmers working with the project cut their estimated Since 2009, farmers and conservation groups in average phosphorus runoff and erosion almost in half, Wisconsin have worked together to test whether it is keeping an estimated average 4,400 pounds of phosphorus possible to target efforts to improve water quality to and 1,300 tons of sediment out of the water each year. have the greatest impact at the lowest possible cost. Just one year after fully implementing targeted changes The idea was to use science to target conservation to agricultural practices on approximately one third practices on those fields and pastures with the greatest of the crop and pasture acres in the watershed, water potential for contributing nutrients to streams. quality has improved. Launching a Pilot Project in Driftless Area Bypassed by the glaciers, the Driftless Area in southwest Wisconsin is characterized by steep- sided ridges and miles of rivers and smaller tributary streams that eventually drain into the Mississippi River. The pilot project took place in two sub-watersheds Changing crop rotations to increase cover on fields in winter gives the Kellers to the Pecatonica River: Pleasant Valley Branch another source of feed for some of their herd. -

NATURAL RESOURCES (Updated Excerpt from Jo Daviess Comprehensive Plan Baseline Data)

ATTACHMENT F: NATURAL RESOURCES (Updated excerpt from Jo Daviess Comprehensive Plan Baseline Data) The natural resources in Jo Daviess County are unique relative to the rest of the state and much of the mid-west because the county is part of the Wisconsin Driftless Region bypassed by continental glaciers of the Ice Age. This region covers parts of southern Minnesota and Wisconsin, Northwestern Illinois and Northeastern Iowa. Glaciated areas were leveled, strewn with glacial debris or "drift" and dotted with lakes and ponds. The driftless areas, on the other hand, have bedrock close to the surface into which deep valleys have been carved by millions of years of weather and erosion. In Jo Daviess County, streams are numerous and the only two lakes are man-made. The relief from the higher ridges to the valley floors is typically 300 feet or more creating a rugged and scenic landscape. Ecosystems can be found in this landscape that are older than those found in glaciated areas. Geology The topography of Jo Daviess County is characterized by rugged relief unique to most of Illinois. Our county, located in the far northwestern corner of the state, is in an area spared by the major glaciations of the last two million years. It is, accordingly, called the "Driftless Area" by geologists, the term "drift" referring to material deposited by glacial activity. The visible landscape that we see today began during the Paleozoic Era (570 to 245 million years ago) when shallow seas repeatedly inundated the interior of the continent. Shells of marine animals, along with muds, silts and sands from eroding highlands, were periodically deposited in those sea bottoms. -

To Prairie Preserves

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) A GUIDE TO MINNESOTA PRAIRIES By Keith M. Wendt Maps By Judith M. Ja.cobi· Editorial Assistance By Karen A. Schmitz Art and Photo Credits:•Thorn_as ·Arter, p. 14 (bottom left); Kathy Bolin, ·p: 14 (top); Dan Metz, pp. 60, 62; Minnesota Departme'nt of Natural Resources, pp. '35 1 39, 65; U.S. Department of Agriculture, p. -47; Keith Wendt, cover, pp~ 14 (right), 32, 44; Vera Wohg, PP· 22, 43, 4a. · · ..·.' The Natural Heritage Program Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Box 6, Centennial Office Building . ,. St. Paul; MN 55155 ©Copyright 1984, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resource.s CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................... Page 3 INTRODUCTION .................................... Page 5 MINNESOTA PRAIRIE TYPES ........................... Page 6 PROTECTION STATUS OF MINNESOTA PRAIRIES ............ Page 12 DIRECTORY OF PRAIRIE PRESERVES BY REGION ............ Page 15 Blufflands . Page 18 Southern Oak Barrens . Page 22 Minnesota River Valley ............................. Page 26 Coteau des Prairies . Page 32 Blue Hills . Page 40 Mississippi River Sand Plains ......................... Page 44 Red River Valley . Page 48 Aspen Parkland ................................... Page 62 REFERENCES ..................................... Page 66 INDEX TO PRAIRIE PRESERVES ......................... Page 70 2 PREFACE innesota has established an outstanding system of tallgrass prairie preserves. No state M in the Upper Midwest surpasses Minnesota in terms of acreage and variety of tallgrass prairie protected. Over 45,000 acres of native prairie are protected on a wide variety of landforms that span the 400 mile length of the state from its southeast to northwest corner. -

The Driftless Area – a Physiographic Setting (Dale K

A Look Back at Driftless Area Science to Plan for Resiliency in an Uncertain Future th Special Publication of the 11 Annual Driftless Area Symposium 1 A Look Back at Driftless Area Science to Plan for Resiliency in an Uncertain Future Special Publication of the 11th Annual Driftless Area Symposium Radisson Hotel, La Crosse, Wisconsin February 5th-6th, 2019 Table of Contents: Preface: A Look Back at Driftless Area Science to Plan for Resiliency in an Uncertain Future (Daniel C. Dauwalter, Jeff Hastings, Marty Melchior, and J. “Duke” Welter) ........................................... 1 The Driftless Area – A Physiographic Setting (Dale K. Splinter) .......................................................... 5 Driftless Area Land Cover and Land Use (Bruce Vondracek)................................................................ 8 Hydrology of the Driftless Area (Kenneth W. Potter) ........................................................................... 15 Geology and Geomorphology of the Driftless Area (Marty Melchior) .............................................. 20 Stream Habitat Needs for Brown Trout and Brook Trout in the Driftless Area (Douglas J. Dieterman and Matthew G. Mitro) ............................................................................................................ 29 Non-Game Species and Their Habitat Needs in the Driftless Area (Jeff Hastings and Bob Hay) .... 45 Climate Change, Recent Floods, and an Uncertain Future (Daniel C. Dauwalter and Matthew G. Mitro) ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Pecatonica River Rapid Watershed Assessment Document

PECATONICA RIVER WATERSHED (WI) HUC: 07090003 Wisconsin Illinois Rapid Watershed Assessment Pecatonica River Watershed Rapid watershed assessments provide initial estimates of where conservation investments would best address the concerns of landowners, conservation districts, and other community organizations and stakeholders. These assessments help landowners and local leaders set priorities and determine the best actions to achieve their goals. Wisconsin June 2008 The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington DC 20250-9410, or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. PECATONICA RIVER WATERSHED (WI) HUC: 07090003 Contents INTRODUCTION 1 COMMON RESOURCE AREAS 3 ASSESSMENT OF WATERS 5 SOILS 7 DRAINAGE CLASSIFICATION 8 FARMLAND CLASSIFICATION 9 HYDRIC SOILS 10 LAND CAPABILITY CLASSIFICATION 11 RESOURCE CONCERNS 12 PRS PERFORMANCE MEASURES 12 CENSUS AND SOCIAL DATA (RELEVANT) 13 POPULATION ETHNICITY 14 URBAN POPULATION 14 ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPES 15 WATERSHED ASSESSMENT 16 WATERSHED PROJECTS, STUDIES, MONITORING, ETC. 16 PARTNER GROUPS 17 FOOTNOTES/BIBLIOGRAPHY 18 PECATONICA RIVER WATERSHED (WI) HUC: 07090003 INTRODUCTION 1. The Pecatonica River watershed encompasses over 1.2 million acres southwest Wisconsin and northwest Illinois. -

Driftless Area - Wikipedia Visited 02/19/2020

2/19/2020 Driftless Area - Wikipedia Visited 02/19/2020 Driftless Area The Driftless Area is a region in southwestern Wisconsin, southeastern Minnesota, northeastern Iowa, and the extreme northwestern corner of Illinois, of the American Midwest. The region escaped the flattening effects of glaciation during the last ice age and is consequently characterized by steep, forested ridges, deeply carved river valleys, and karst geology characterized by spring-fed waterfalls and cold-water trout streams. Ecologically, the Driftless Area's flora and fauna are more closely related to those of the Great Lakes region and New England than those of the broader Midwest and central Plains regions. Colloquially, the term includes the incised Paleozoic Plateau of southeastern Minnesota and northeastern Relief map showing primarily the [1] Iowa. The region includes elevations ranging from 603 to Minnesota part of the Driftless Area. The 1,719 feet (184 to 524 m) at Blue Mound State Park and wide diagonal river is the Upper Mississippi covers 24,000 square miles (62,200 km2).[2] The rugged River. In this area, it forms the boundary terrain is due both to the lack of glacial deposits, or drift, between Minnesota and Wisconsin. The rivers entering the Mississippi from the and to the incision of the upper Mississippi River and its west are, from the bottom up, the Upper tributaries into bedrock. Iowa, Root, Whitewater, Zumbro, and Cannon Rivers. A small portion of the An alternative, less restrictive definition of the Driftless upper reaches of the Turkey River are Area includes the sand Plains region northeast of visible west of the Upper Iowa. -

Ecoregions of North Dakota and South Dakota Hydrography, and Land Use Pattern

1 7 . M i d d l e R o c k i e s The Middle Rockies ecoregion is characterized by individual mountain ranges of mixed geology interspersed with high elevation, grassy parkland. The Black Hills are an outlier of the Middle Rockies and share with them a montane climate, Ecoregions of North Dakota and South Dakota hydrography, and land use pattern. Ranching and woodland grazing, logging, recreation, and mining are common. 17a Two contrasting landscapes, the Hogback Ridge and the Red Valley (or Racetrack), compose the Black Hills 17c In the Black Hills Core Highlands, higher elevations, cooler temperatures, and increased rainfall foster boreal Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, This level III and IV ecoregion map was compiled at a scale of 1:250,000; it Literature Cited: Foothills ecoregion. Each forms a concentric ring around the mountainous core of the Black Hills (ecoregions species such as white spruce, quaking aspen, and paper birch. The mixed geology of this region includes the and quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial depicts revisions and subdivisions of earlier level III ecoregions that were 17b and 17c). Ponderosa pine cover the crest of the hogback and the interior foothills. Buffalo, antelope, deer, and elk highest portions of the limestone plateau, areas of schists, slates and quartzites, and large masses of granite that form the framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems originally compiled at a smaller scale (USEPA, 1996; Omernik, 1987). This Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the United still graze the Red Valley grasslands in Custer State Park. -

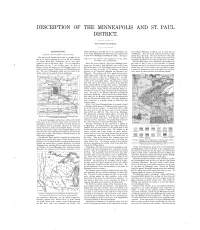

Description of the Minneapolis and St. Paul District

DESCRIPTION OF THE MINNEAPOLIS AND ST. PAUL DISTRICT. By Frederick W. Sardeson. INTRODUCTION. district described in this folio lies in the northwestern part and southern Wisconsin, in Illinois, and in Iowa, but not of the Upper Mississippi basin subprovince and embraces the in Minnesota. They are chiefly dolomitic limestones, which LOCATION AND RELATIONS OF THE DISTRICT. junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota valleys. (See fig. 2.) include many coral reefs. They were laid down in clear, shal The district here described is bounded by parallels 44° 45' low seas while this region was a low coastal plain between the and 45° 15' and by meridians 93° and 93° 30' and comprises OUTLINE OF THE GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY OF THE UPPEE Laurentian highlands on the north and the sea on the south. the Anoka, White Bear, Minneapolis, and St. Paul quad MISSISSIPPI BASIN SUBPROVINCE. The Devonian system covers the Silurian and overlaps it on rangles, an area of 846 square miles. It is in southeastern Extent and general relations. The Upper Mississippi basin the north so that it rests on the Ordovician in southern Minnesota (see fig. 1) and includes nearly the whole of subprovince lies west of Lake Michigan, east of the Coteau Minnesota (see fig. 3), but elsewhere it has been more strongly Ramsey County, the greater part of Hennepin County, and des Prairies, north of the Carboniferous basin or coal fields of eroded away and is less extensive than the Silurian system. smaller parts of Anoka, Dakota, Scott, and Washington coun Illinois and Iowa, and south of The Ranges, a southward It consists of limestones and clay shales, which were laid down ties. -

WEBSITE PARKS LISTING.Pdf

WHICH IOWA PARKS HAVE YOU CHECKED OUT? NORTHWEST Buena Vista County Conservation Park Lake Pahoja Recreation Area Peterson (Buena Vista) Inwood (Lyon) Featherstone Memorial Park Dog Creek Park Manson (Calhoun) Sutherland (O’Brien) Martin’s Access Hawkeye Point Campground Cherokee (Cherokee) Sibley (Osceola) Scharnberg Park Lost Island - Huston Park Everly (Clay) Ruthven (Palo Alto) Kenue Park Five Ridge Prairie Okoboji (Dickinson) Westfield(Plymouth) Tuttle Lake Recreation Area Meredith Park Dolliver (Emmet) (Pocahontas) Joe Sheldon Park Hagge Park Humboldt (Humboldt) Sac City (Sac) Moorehead Pioneer Park Sandy Hollow Recreation Area Ida Grove (Ida) Sioux Center (Sioux) Smith Lake Park Dorothy Pecaut Nature Center Algona (Kossuth) Sioux City (Woodbury) WEST CENTRAL Littlefield Recreation Area Willow Lake Recreation Area Exira (Audubon) Woodbine (Harrison) Swan Lake State Park Peters Park Carroll (Carroll) Rodney (Monona) Cold Springs Park Hitchcock Nature Center Lewis (Cass) Honey Creek (Pottawattamie) Yellow Smoke Park Nishna Bend Recreation Area Denison (Crawford) Harlan (Shelby) Nations Bridge Park Stuart (Guthrie) SOUTHWEST Mormon Trail Park Pierce Creek Recreation Area Bridgewater (Adair) Essex (Page) Lake Icaria Poe Hollow Park Corning (Adams) Mount Ayr (Ringgold) Fremont County Campground & Golf Course Sand’s Timber Recreation Area Sidney (Fremont) Blockton (Taylor) Pony Creek Park Three Mile Lake Pacific Junction(Mills) Afton (Union) Hacklebarney Woods Villisca (Montgomery) NORTH CENTRAL Beaver Meadows Park Calkins Nature Area -

Geology and Geomorphology of the Driftless Area

Geology and Geomorphology of the Driftless Area Marty Melchiora,1 aInter-Fluve, Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA This manuscript was compiled on February 5, 2019 1. The geology of the Driftless Area directly influences fluvial geo- morphic processes, resulting in stream systems that are unique to the region but not uncommon worldwide. 2. Land management practices impact fluvial geomorphic processes in the Driftless Area streams by changing hydrology and sediment sources, transport, and deposition. 3. The complexity of interaction between climate, landuse, soils, ge- ology, ecology and geomorphic processes in Driftless Area require careful consideration, and generalities regarding cause and effect should be avoided when making management decisions related to landuse and ecology. Geology | Geomorphology | Sediment Transport and Deposition | Chan- nel Geometry | Streambank Erosion | Riparian Vegetation Fig. 1. Bedload originating from eroding streambanks is often deposited in channel o understand the geomorphology of Driftless Area immediately downstream of the eroding outer bend. Tstreams, we must consider not only fluvial geomorphology, or the form and processes of moving water on the landscape, but also the surficial geology and landuse history, particularly by deposits of windblown fine soils called loess. The larger with regard to vegetation changes. This section examines basic river valleys, such as the Mississippi and Wisconsin Rivers, fluvial geomorphic principles, and looks at how glacial and have high bluffs rising over 500-ft (150-m) above the level of post glacial geology and landuse affects channel forms and the Mississippi. These large rivers and their tributaries have processes in the Driftless Area. eroded through Paleozoic Era sedimentary rock, primarily Ordivician dolomite, limestone, sandstone and shale.