A Brlef Hlstory OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

LOOKING AT MUSIC: SIDE 2 EXPLORES THE CREATIVE EXCHANGE BETWEEN MUSICIANS AND ARTISTS IN NEW YORK CITY IN THE 1970s AND 1980s Photography, Music, Video, and Publications on Display, Including the Work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Blondie, Richard Hell, Sonic Youth, and Patti Smith, Among Others Looking at Music: Side 2 June 10—November 30, 2009 The Yoshiko and Akio Morita Gallery, second floor Looking at Music: Side 2 Film Series September—November 2009 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, June 5, 2009—The Museum of Modern Art presents Looking at Music: Side 2, a survey of over 120 photographs, music videos, drawings, audio recordings, publications, Super 8 films, and ephemera that look at New York City from the early 1970s to the early 1980s when the city became a haven for young renegade artists who often doubled as musicians and poets. Art and music cross-fertilized with a vengeance following a stripped-down, hard-edged, anti- establishment ethos, with some artists plastering city walls with self-designed posters or spray painted monikers, while others commandeered abandoned buildings, turning vacant garages into makeshift theaters for Super 8 film screenings and raucous performances. Many artists found the experimental music scene more vital and conducive to their contrarian ideas than the handful of contemporary art galleries in the city. Artists in turn formed bands, performed in clubs and non- profit art galleries, and self-published their own records and zines while using public access cable channels as a venue for media experiments and cultural debates. Looking at Music: Side 2 is organized by Barbara London, Associate Curator, Department of Media and Performance Art, The Museum of Modern Art, and succeeds Looking at Music (2008), an examination of the interaction between artists and musicians of the 1960s and early 1970s. -

A Conversation with Dr Dieter Buchhart Co-Curator of the Exhibition: 'Basquiat: Boom for Real' at the Barbican, London

By Stephanie Bailey November 16, 2017 A conversation with Dr Dieter Buchhart Co-curator of the exhibition: 'Basquiat: Boom for Real' at the Barbican, London Dr Dieter Buchhart. Photo: Mathias Kessler. Curator and scholar Dr Dieter Buchhart is the co-curator of the Barbican's current exhibition, Basquiat: Boom for Real (21 September 2017–28 January 2018), alongside Barbican curator Eleanor Nairne. Organised in collaboration with the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and with the support of the Basquiat Exhibition Circle and the Basquiat family, the exhibition brings together more than 100 works from international museums and private collections, and represents the first major institutional exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat's work since the artist's 1984 show at Edinburgh's Fruitmarket Gallery. (Though the Serpentine did stage a small exhibition of major paintings from 1981 to 1988 between 6 March and 21 April 1996—described as 'the first solo showing ... in a public gallery in Britain since his death.') © Nicholas Taylor, Jean-Michel Basquiat dancing at the Mudd Club (1979). Installation view: Basquiat: Boom for Real, Barbican Art Gallery, London (21 September 2017–28 January 2018). Courtesy Barbican Art Gallery. Photo: © Tristan Fewings / Getty Images. Boom for Real offers an impressive overview of the life and work of an artist Buchhart has described as conceptual, above all—an identification that manifests in the sheer explosion of creativity that unfolds over two floors of the Barbican Art Gallery where this exhibition is staged. Aside from an excellent selection of paintings—including Leonardo da Vinci's Greatest Hits (1982) and a self-portrait from 1984—and a series of images that document the artist's days as street artist duo SAMO© (along with school mate Al Diaz), there's a room dedicated to New York / New Wave, a group show Basquiat participated in at PS1 in February 1981, curated by Diego Cortez; and another in which Downtown 81 (1980–81/2000), in which Basquiat plays a young struggling artist in the City, is screened on a loop. -

The Direct Action Politics of US Punk Collectives

DIY Democracy 23 DIY Democracy: The Direct Action Politics of U.S. Punk Collectives Dawson Barrett Somewhere between the distanced slogans and abstract calls to arms, we . discovered through Gilman a way to give our politics some application in our actual lives. Mike K., 924 Gilman Street One of the ideas behind ABC is breaking down the barriers between bands and people and making everyone equal. There is no Us and Them. Chris Boarts-Larson, ABC No Rio Kurt Cobain once told an interviewer, “punk rock should mean freedom.”1 The Nirvana singer was arguing that punk, as an idea, had the potential to tran- scend the boundaries of any particular sound or style, allowing musicians an enormous degree of artistic autonomy. But while punk music has often served as a platform for creative expression and symbolic protest, its libratory potential stems from a more fundamental source. Punk, at its core, is a form of direct action. Instead of petitioning the powerful for inclusion, the punk movement has built its own elaborate network of counter-institutions, including music venues, media, record labels, and distributors. These structures have operated most notably as cultural and economic alternatives to the corporate entertainment industry, and, as such, they should also be understood as sites of resistance to the privatizing 0026-3079/2013/5202-023$2.50/0 American Studies, 52:2 (2013): 23-42 23 24 Dawson Barrett agenda of neo-liberalism. For although certain elements of punk have occasion- ally proven marketable on a large scale, the movement itself has been an intense thirty-year struggle to maintain autonomous cultural spaces.2 When punk emerged in the mid-1970s, it quickly became a subject of in- terest to activists and scholars who saw in it the potential seeds of a new social movement. -

Xfr Stn: Public Programs

XFR STN: PUBLIC PROGRAMS 7/25 | 7 PM | FIFTH FLOOR PANEL DISCUSSIONS LIZA BÉAR & MILLY IATROU, 7/18 | 6 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER COMMUNICATIONS UPDATE MOVING IMAGE ARTISTS’ The weekly artist public access Communications DISTRIBUTION THEN & NOW Update, later renamed Cast Iron TV, ran continuously on Manhattan Cable’s Channel D from 1979 to 1991. Filmmakers Liza Béar and Milly Iatrou present indi- An assembly of participants from the MWF Video Club vidual segments cablecast in the Communications and Colab TV projects includes opening remarks from Update 1982 series: “The Very Reverend Deacon b. Alan W. Moore, Andrea Callard, Michael Carter, Coleen Peachy,” “A Matter of Facts,” “Crime Tales,” “Lighter Fitzgibbon, Nick Zedd, and members of the New Than Air,” and “Oued Nefifik: A Foreign Movie.” Museum’s “XFR STN” team. Followed by an open dis- cussion with the audience, facilitated by Alexis Bhagat. 8/1 | 7–8 PM | FIFTH FLOOR MITCH CORBER, THE ORIGINAL 9/7 | 1 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER WONDER ALWAYS ALREADY OBSOLETE: MEDIA CONVERGENCE, ACCESS, Mitch Corber has dedicated his career to production for NYC public access cable TV, working closely with AND PRESERVATION Colab TV and the MWF Video Club. Corber will present a selection of early work, as well as videos from his Beyond media specificity, what happens after video- long-running program Poetry Thin Air. tape has been absorbed into a new medium—and what are the implications of these continuing shifts in format for how we understand access and preserva- 8/8 | 7 PM | NEW MUSEUM THEATER tion? This panel considers forms of preservation that have emerged across analog, digital, and networked CLAYTON PATTERSON: platforms in conjunction with new forms of circulation FROM THE UNDERGROUND AND and distribution. -

Lenguajes Artísticos Y Vanguardias En La No Wave

UNIVERSIDAD DE LA LAGUNA. GRADO EN HISTORIA DEL ARTE. Lenguajes artísticos y vanguardias en la No Wave Trabajo Fin de Grado Adriana García Benítez 23/09/2014 Tutor del trabajo: Dr. Pompeyo Pérez Díaz. ÍNDICE 1. Metodología y objetivos. Pág. 3 2. Introducción a la No Wave . Pág. 5 a. Influencias de la No Wave . b. New Wave y No Wave . c. Donde se produce el encuentro: The Mudd Club. d. Fanzines. 3. La música de la No Wave . Pág. 19 4. El cine y los directores ( filmmakers ) de la No Wave : Pág. 24 a. Vivienne Dick. b. Beth B c. Susan Seidelman. d. Jim Jarmusch. e. Paul Auster. 5. No solo pintura: Pág. 35 a. Jean Michael Basquiat. b. Robert Longo. 6. Conclusiones. Pág. 40 7. Bibliografía. Pág. 44 2 METODOLOGÍA Y OBJETIVOS. Con el presente trabajo se pretende realizar una inmersión a las manifestaciones artísticas que se dan en el entorno No Wave de Nueva York entre los años 70 y 80. El objetivo principal es estudiar las relaciones que existen entre las figuras más relevantes tanto en artes plásticas como en música y cine. El título “Lenguajes artísticos y vanguardias” responde a una intención de establecer las colaboraciones y cruces entre las artes, ya que al tratarse de un movimiento heterogéneo, se puede y se busca estudiar diferentes artistas y objetos artísticos. Este aspecto, a nivel personal, es otro de los que nos convencieron para abordar este tema, ya que nos permite indagar en varias manifestaciones en lugar de centrarnos en una única expresión, así como en los artistas clave del momento y como encajan todos los elementos en un lugar y momento determinados. -

Notes CHAPTER 1 6

notes CHAPTER 1 6. The concept of the settlement house 1. Mario Maffi, Gateway to the Promised originated in England with the still extant Land: Ethnic Cultures in New York’s Lower East Tonybee Hall (1884) in East London. The Side (New York: New York University Press, movement was tremendously influential in 1995), 50. the United States, and by 1910 there were 2. For an account of the cyclical nature of well over four hundred settlement houses real estate speculation in the Lower East Side in the United States. Most of these were in see Neil Smith, Betsy Duncan, and Laura major cities along the east and west coasts— Reid, “From Disinvestment to Reinvestment: targeting immigrant populations. For an over- Mapping the Urban ‘Frontier’ in the Lower view of the settlement house movement, see East Side,” in From Urban Village to East Vil- Allen F. Davis, Spearheads for Reform: The lage: The Battle for New York’s Lower East Side, Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, ed. Janet L. Abu-Lughod, (Cambridge, Mass.: 1890–1914 (New York: Oxford University Blackwell Publishers, 1994), 149–167. Press, 1967). 3. James F. Richardson, “Wards,” in The 7. The chapter “Jewtown,” by Riis, Encyclopedia of New York City, ed. Kenneth T. focuses on the dismal living conditions in this Jackson (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University ward. The need to not merely aid the impover- Press, 1995), 1237. The description of wards in ished community but to transform the physi- the Encyclopedia of New York City establishes cal city became a part of the settlement work. -

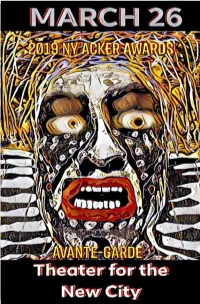

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Oral History Interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington, 2009 January 21 and May 22

Oral history interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington, 2009 January 21 and May 22 Funding for this interview was provided by the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington on January 21 and May 22, 2009. The interview took place at in New York, New York, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Wendy Olsoff, Penny Pilkington, and James McElhinney have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES McELHINNEY: This is James McElhinney speaking with Penny Pilkington and Wendy Olstroff. PENNY PILKINGTON: Olsoff. O-L-S-O-F-F. MR. McELHINNEY: Olsoff? WENDY OLSOFF: Right. MR. McELHINNEY: At 432 Lafayette Street in New York, New York, on January 21, 2009. So for the transcriber, I’m going to ask you to just simply introduce yourselves so that the person who is writing out the interview will be able to identify— [END OF DISC 1, TRACK 1.] MR. McELHINNEY: —who’s who by voice. -

Rent Glossary of Terms

Rent Glossary of Terms 11th Street and Avenue B CBGB’s – More properly CBGB & OMFUG, a club on Bowery Ave between 1st and 2nd streets. The following is taken from the website http://www.cbgb.com. It is a history written by Hilly Kristal, the founder of CBGB and OMFUG. The question most often asked of me is, "What does CBGB stand for?" I reply, "It stands for the kind of music I intended to have, but not the kind that we became famous for: COUNTRY BLUEGRASS BLUES." The next question is always, "but what does OMFUG stand for?" and I say "That's more of what we do, It means OTHER MUSIC FOR UPLIFTING GORMANDIZERS." And what is a gormandizer? It’s a voracious eater of, in this case, MUSIC. […] The obvious follow up question is often "is this your favorite kind of music?" No!!! I've always liked all kinds but half the radio stations all over the U.S. were playing country music, cool juke boxes were playing blues and bluegrass as well as folk and country. Also, a lot of my artist/writer friends were always going off to some fiddlers convention (bluegrass concert) or blues and folk festivals. So I thought it would be a whole lot of fun to have my own club with all this kind of music playing there. Unfortunately—or perhaps FORTUNATELY—things didn't work out quite the way I 'd expected. That first year was an exercise in persistence and a trial in patience. My determination to book only musicians who played their own music instead of copying others, was indomitable. -

10 Stanton St., Apt,* 3 Mercer / OLX 102 Forayti * 307 Mtt St 307 Mott St

Uza 93 Grand' St. Scott 54 Thoaas", 10013 ^ •Burne, Tim -Coocey, Robert SCorber, Hitch 10 stanton St., Apt,* 10002-••-•-677-744?* -EinG,' Stefan 3 Mercer / \ - • • ^22^-5159 ^Ensley, Susan Colen . 966-7786 s* .Granet, Ilona 281 Mott SU, 10002 226-7238* V Hanadel, Ksith 10 Bleecl:-?4St., 10012 . , 'Horowitz, Beth "' Thomas it,, 10013 ' V»;;'.•?'•Hovagiicyan, Gorry ^V , Loneendvke. Paula** 25 Park PI.-- 25 E, 3rd S . Maiwald, Christa OLX 102 Forayti St., 10002 Martin, Katy * 307 MotMttt SStt ayer. Aline 29 John St. , Miller, Vestry £ 966-6571 226-3719^* }Cche, Jackie Payne, -Xan 102 Forsyth St/, 10002 erkinsj Gary 14 Harrieon?;St., 925-229X Slotkin, Teri er, 246 Mott 966-0140 Tillett, Seth 11 Jay St 10013 Winters, Robin P.O.B. 751 Canal St. Station E. Houston St.) Gloria Zola 93 Warren St. 10007 962 487 Valery Taylor 64 Fr'^hkliii St. Alan 73 B.Houston St. B707X Oatiirlno Sooplk 4 104 W.Broedway "An Association," contact list, 1977 (image May [977 proved to be an active month for the New York art world and its provided by Alan Moore) growing alternatives. The Guggenheim Museum mounted a retrospective of the color-field painter Kenneth Notand; a short drive upstate, Storm King presented monumental abstract sculptures by Alexander Liberman; and the Museum of Modern Art featured a retro.spective of Robert Rauschenberg's work. As for the Whitney Museum of American Art, contemporary reviews are reminders that not much has changed with its much-contested Biennial of new art work, which was panned by The Village Voice. The Naiion, and, of course, Hilton Kramer in the New York Times, whose review headline, "This Whitney Biennial Is as Boring as Ever," said it all.' At the same time, An in America reported that the New Museum, a non- collecting space started by Marcia Tucker some five months earlier, was "to date, simply an office in search of exhibition space and benefac- tors."^ A month later in the same magazine, the critic Phil David E. -

John Lurie/Samuel Delany/Vladimir Mayakovsky/James Romberger Fred Frith/Marty Thau/ Larissa Shmailo/Darius James/Doug Rice/ and Much, Much More

The World’s Greatest Comic Magazine of Art, Literature and Music! Number 9 $5.95 John Lurie/Samuel Delany/Vladimir Mayakovsky/James Romberger Fred Frith/Marty Thau/ Larissa Shmailo/Darius James/Doug Rice/ and much, much more . SENSITIVE SKIN MAGAZINE is also available online at www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com. Publisher/Managing Editor: Bernard Meisler Associate Editors: Rob Hardin, Mike DeCapite & B. Kold Music Editor: Steve Horowitz Contributing Editors: Ron Kolm & Tim Beckett This issue is dedicated to Chris Bava. Front cover: Prime Directive, by J.D. King Back cover: James Romberger You can find us at: Facebook—www.facebook.com/sensitiveskin Twitter—www.twitter.com/sensitivemag YouTube—www.youtube.com/sensitiveskintv We also publish in various electronic formats (Kindle, iOS, etc.), and have our own line of books. For more info about SENSITIVE SKIN in other formats, SENSITIVE SKIN BOOKS, and books, films and music by our contributors, please go to www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/store. To purchase back issues in print format, go to www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/back-issues. You can contact us at [email protected]. Submissions: www.sensitiveskinmagazine.com/submissions. All work copyright the authors 2012. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of both the publisher and the copyright owner. All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. ISBN-10: 0-9839271-6-2 Contents The Forgetting -

82 SECOND AVENUE 1,150 SF Availble for Lease Between East 4Th and 5Th Streets EAST VILLAGE NEW YORK | NY

RETAIL SPACE 82 SECOND AVENUE 1,150 SF Availble for Lease Between East 4th and 5th Streets EAST VILLAGE NEW YORK | NY SPACE A SPACE B SPACE DETAILS GROUND FLOOR LOWER LEVEL LOCATION NEIGHBORS Between East 4th and 5th Streets Nomad, Atlas Café, Frank, The Mermaid Inn, Coopers Craft & SIZE Kitchen, Bank Ant, The Bean Space A COMMENTS EXISTING Ground Floor 700 SF Prime East Village restaurant WALK-IN Basement 300 SF opportunity SPACE A REFRIGERATOR 300 SF Space B Vented for cooking use; gas and electric in place Ground Floor 450 SF KITCHEN New direct long-term lease, Basement 200 SF no key money FRONTAGE Space A Second Avenue 12 FT Space B Second Avenue 10 FT SPACE A TRANSPORTATION 700 SF 2019 Ridership Report Second Avenue Astor Place 6 RESTAURANT Annual 5,583,944 Annual 5,502,925 Weekday 16,703 Weekday 17,180 Weekend 24,564 Weekend 21,108 12 FT SECOND AVENUE EAST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET WEST 14TH STREET EAST 14TH STREET Optyx Artichokes Pizza Petopia Akina Sushi Muzarella Pizza Bright Horizons Brothers Candy & Grocery M&J Nature Joe’s Pizza Krust Lex AMALGAMATED Vanessa’s Regina The City Synergy AVENUE SECOND Taverna Kyclades Republic Dumplings AVENUE FIRST Exchange AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS AVENUE Champion BANK Pizza Check Nugget Gourmet Big Arc Chicken AVENUE C AVENUE AVENUE A AVENUE Wine & City Le Café Coee B AVENUE Pizza First Lamb King’s Way Cashing Spot Baohaus Tortuga Vinny Vicenz Jewelry Spirits AVENUE THIRD Planet Rose FIFTH AVENUE Streets Cava Grill Revolution Shabu Food Corp Discount PJ’s Grocery