THE-WITCH-Final-Press-Notes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jennifer Ricchiazzi, Csa

JENNIFER RICCHIAZZI, CSA www.jenniferricchiazzi.com Selected Film & Television Credits FUTRA DAYS (Pre-Production/Currently Casting) Producer: Ryan David, Orian Williams, David Zonshine. Director/Writer: Ryan David. SHOOTING HEROIN (Post-Production) Producer: Mark Joseph. Director/Writer: Spencer Folmar. Starring: Alan Powell, Cathy Moriarty, Sherilyn Fenn, Nicholas Turturro THE UNSPOKEN (Pre-Production) Winterland Pictures. Producers: Lionel Hicks, Rebecca Tranter. Director/Writer: Andrew Hunt FIGHTING CHANCE (Pre-Production) Producers: Scott Rosenfelt, Ron Winston. Director: Mikael Salomon FALL OF EDEN (Pre-Production) Producer: Mark G Mathis. Director: Susan Dynner. Attached: Dylan McDermott, Brianna Hildebrand. BLINDED BY ED (Pre-Production) Producer: Kristy Lash. Director/Writer: Chris Fetchko. Attached: Katrina Bowden. REAGAN (Pre-Production) Independent. Producer: Mark Joseph; Executive Producer: Dawn Krantz. Director: John G. Avildsen. Attached: Jon Voight and Dennis Quaid. HAUNTING OF THE MARY CELESTE Vertical Entertainment. Producers: Norman Dreyfuss, Brian Dreyfuss, Justin Ambrosino. Writer: David Ross; Executive Producers: Eric Brodeur, Jerome Oliver. Director: Shana Betz. Starring: Emily Swallow. SOLVE Mobile Series. Vertical Networks; Snapchat. THE STOLEN Independent/Cork Films Ltd. Producer/Writer: Emily Corcoran; Executive Producer: Julia Palau. Director/Co-Writer: Niall Johnson. Starring: Alice Eve, Jack Davenport. THE CLAPPER (Tribeca Film Festival 2017) Independent. Producer: Robin Schorr. Director: Dito Montiel. Starring: -

Star Channels, Jan. 5-11, 2020

JANUARY 5 - 11, 2020 staradvertiser.com HEARING VOICES In an innovative, exciting departure from standard television fare, NBC presents Zoe’s Extraordinary Playlist. Jane Levy stars as the titular character, Zoey Clarke, a computer programmer whose extremely brainy, rigid nature often gets in the way of her ability to make an impression on the people around her. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 7, on NBC. Delivered over 877,000 hours of programming Celebrating 30 years of empowering our community voices. For our community. For you. olelo.org 590191_MilestoneAds_2.indd 2 12/27/19 5:22 PM ON THE COVER | ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST A penny for your songs ‘Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist’ ...,” narrates the first trailer for the show, “... her new ability, when she witnesses an elabo- what she got, was so much more.” rate, fully choreographed performance of DJ premieres on NBC In an event not unlike your standard super- Khaled’s “All I Do is Win,” but Mo only sees “a hero origin story, an MRI scan gone wrong bunch of mostly white people drinking over- By Sachi Kameishi leaves Zoey with the ability to access people’s priced coffee.” TV Media innermost thoughts and feelings. It’s like she It’s a fun premise for a show, one that in- becomes a mind reader overnight, her desire dulges the typical musical’s over-the-top, per- f you’d told me a few years ago that musicals to fully understand what people want from formative nature as much as it subverts what would be this culturally relevant in 2020, I her seemingly fulfilled. -

'James Cameron's Story of Science Fiction' – a Love Letter to the Genre

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 27 - May 3, 2018 A S E K C I L S A M M E L I D 2 x 3" ad D P Y J U S P E T D A B K X W Your Key V Q X P T Q B C O E I D A S H To Buying I T H E N S O N J F N G Y M O 2 x 3.5" ad C E K O U V D E L A H K O G Y and Selling! E H F P H M G P D B E Q I R P S U D L R S K O C S K F J D L F L H E B E R L T W K T X Z S Z M D C V A T A U B G M R V T E W R I B T R D C H I E M L A Q O D L E F Q U B M U I O P N N R E N W B N L N A Y J Q G A W D R U F C J T S J B R X L Z C U B A N G R S A P N E I O Y B K V X S Z H Y D Z V R S W A “A Little Help With Carol Burnett” on Netflix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) (Carol) Burnett (DJ) Khaled Adults Place your classified ‘James Cameron’s Story Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 (Taraji P.) Henson (Steve) Sauer (Personal) Dilemmas ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End (Mark) Cuban (Much-Honored) Star Advice 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise (Wanda) Sykes (Everyday) People Adorable Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lisa) Kudrow (Mouths of) Babes (Real) Kids of Science Fiction’ – A love letter Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 to the genre for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light,3.5" ad “AMC Visionaries: James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction,” Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post premieres Monday on AMC. -

Star Channels, May 20-26

MAY 20 - 26, 2018 staradvertiser.com LEGAL EAGLES Sandra’s (Britt Robertson) confi dence is shaken when she defends a scientist accused of spying for the Chinese government in the season fi nale of For the People. Elsewhere, Adams (Jasmin Savoy Brown) receives a compelling offer. Chief Judge Nicholas Byrne (Vondie Curtis-Hall) presides over the Southern District of New York Federal Court in this legal drama, which wraps up a successful freshman season. Airing Tuesday, May 22, on ABC. WE’RE LOOKING FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY. Are you passionate about an issue? An event? A cause? ¶ũe^eh\Zga^eirhn[^a^Zk][r^fihp^kbg`rhnpbmama^mkZbgbg`%^jnbif^gm olelo.org Zg]Zbkmbf^rhng^^]mh`^mlmZkm^]'Begin now at olelo.org. ON THE COVER | FOR THE PEOPLE Case closed ABC’s ‘For the People’ wraps Deavere Smith (“The West Wing”) rounds example of how the show delves into both the out the cast as no-nonsense court clerk Tina professional and personal lives of the charac- rookie season Krissman. ters. It’s a formula familiar to fans of Shonda The cast of the ensemble drama is now part Rhimes, who’s an executive producer of “For By Kyla Brewer of the Shondaland dynasty, which includes hits the People,” along with Davies, Betsy Beers TV Media “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Scandal” and “How to Get (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Donald Todd (“This Is Us”) Away With Murder.” The distinction was not and Tom Verica (“How to Get Away With here’s something about courtroom lost on Rappaport, who spoke with Murder”). -

Alex Gibney Film

Mongrel Media Presents A Kennedy/Marshall Production In association with Jigsaw Productions and Matt Tolmach Productions An Alex Gibney Film The ARMSTRONG Lie Official Selection Toronto Film Festival 2013 Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html 2 THE ARMSTRONG LIE Written and Directed by ALEX GIBNEY Produced by FRANK MARSHALL MATT TOLMACH ALEX GIBNEY Director of Photography MARYSE ALBERTI Edited by ANDY GRIEVE TIM SQUYRES, A.C.E. Music by DAVID KAHNE Co-Producers JENNIE AMIAS MARK HIGGINS BETH HOWARD Associate Producers BRETT BANKS NICOLETTA BILLI Music Supervisor JOHN MCCULLOUGH 3 The ARMSTRONG Lie Synopsis In 2008, Academy Award® winning filmmaker Alex Gibney set out to make a documentary about Lance Armstrong’s comeback to the world of competitive cycling. Widely regarded as one of the most prominent figures in the history of sports, Armstrong had brought global attention to cycling as the man who had triumphed over cancer and went on to win bicycling’s greatest race, the Tour de France, a record seven consecutive times. Charting Armstrong’s life-story (and given unprecedented access to both the Tour and the man), Gibney began filming what he initially envisioned as the ultimate comeback story – Armstrong’s return from his 2005 retirement and his attempt to win his eighth Tour. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

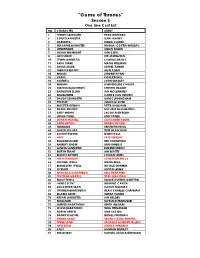

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

NOMINEES for the 39Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 39th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED Paula S. Apsell of PBS’ NOVA to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award October 1st Award Presentation at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 26, 2018 (revised 9.30.18) – Nominations for the 39th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Monday, October 1st, 2018, at a ceremony at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in the Time Warner Complex at Columbus Circle in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “New technologies are opening up endless new doors to knowledge, instantly delivering news and information across myriad platforms,” said Adam Sharp, interim President& CEO, NATAS. “With this trend comes the immense potential to inform and enlighten, but also to manipulate and distort. Today we honor the talented professionals who through their work and creativity defend the highest standards of broadcast journalism and documentary television, proudly providing the clarity and insight each of us needs to be an informed world citizen.” In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to be honoring Paula S. Apsell, Senior Executive Director of PBS’ NOVA, at the 39th News & Documentary Emmy Awards with the Lifetime Achievement Award for her many years of science broadcasting excellence. -

0113.09 Hair Fb Postings

Hi Tribe. What's your Tribe's Name? Every Tribe ever has named themselves! Great opening night. You mean what you are doing and it means a lot to those who come to see you. Your lives will be changed by this tour, so have a blast! (BTW your cast is the best of the 3 B-way stagings I've enjoyed - Less Belting and wonderful harmonizing - much more satisfying thant the over amplified shows that preceded you, plus the meaningfulness of the text is much more apparent in your show than before) Check out Rado on Smothers Brothers show w/ LA Cast in 1968! - -- - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - I did a college production of HAIR in 1977 at Northwestern (http:// www.facebook.com/album.php?id=1117459016&aid=2065972), and then took to the road in the Summer/Fall of 1978 selling computer portraits ("Put your face on a T-shirt!") in state and county fairs. It was while living in a motorhome that summer I read "On the Road" for the first time. Connecting the dots between Neal Cassady / Jack Kerouac / Alan Ginsberg / the Beat Generation / the Merry Pranksters / Counterculture of the 1960's / Summer of Love / Hippies / Yippies / Antiwar movement, etc. has been a lifelong avocation and intellectual pursuit ever since. I hope you will enjoy some of these links and will ultimately write a book about how YOUR consciousness was raised by embracing HAIR, the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical! Robert Mendel IMDB http://mendel.locations.org NEAL CASSADY AND ALAN GINSBERG http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0143944/bio - Biography for Neal Cassady http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neal_Cassady - Neal Cassady http://www.beatbookcovers.com/cassady/ - NEAL CASSADY BOOK COVERS (check out "As Ever" - collected letters between Cassady and Ginsberg http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hair_(musical) -- The theme of opposition to the war that pervades the show is unified by the plot thread that progresses through the book – Claude's moral dilemma over whether to burn his draft card.[51] Pacifism is explored throughout the extended trip sequence in Act 2. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: June 23, 2021 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] PLEASE DOUBLECHECK ALL EVENTS, THINGS ARE STILL BE POSTPONED OR CANCELLED. SOMETIMES FACEBOOK WILL SAY CANCELLED YET WEBSITE STILL SHOWS REGULAR EVENT! JUNE 24 NYC BIG APPLE COMIC CON-Summer Event New Yorker Htl, Manhatten, NY NY www.bigapplecc.com JUNE 25 Virt ANIME: NAUSICAA OF THE VALLEY OF THE WIND group watch event (requires Netflix account) https://www.fanexpocanada.com JUNE 25 Virt STAR WARS TRIVIA: ROGUE ONE round one features Rogue One movie trivia game https://www.fanexpocanada.com JUNE 25-27 S.F. CREATION - SUPERNATURAL Hyatt Regency Htl, San Francisco CA TV series tribute https://www.creationent.com/ JUNE 26-27 N.J. CREATION - STRANGER THINGS NJ Conv Ctr, Edison, NJ (NYC) TV series tribute https://www.creationent.com/ JUNE 27 Virt WIZARD WORLD-STAR TREK GUEST STARS Virtual event w/ cast some parts free, else to buy https://wizardworld.com/ Charlie Brill, Jeremey Roberts, John Rubenstein, Gary Frank, Diane Salinger, Kevin Brief JUNE 27 BTC BUFFALO TIME COUNCIL MEETING 49 Greenwood Pl, Buffalo monthly BTC meeting buffalotime council.org YES!! WE WILL HAVE A MEETING! JULY 8-11 MA READERCON Marriott Htl, Quincy, Mass (Boston) Books & Authors http://readercon.org/ Jeffrey Ford, Ursula Vernon, Vonda N McIntyre (in Memorial) JULY 9-11 T.O. TFCON DELAYED UNTIL DEC 10-12, 2021 Transformers fan-run -

10700990.Pdf

The Dolby era: Sound in Hollywood cinema 1970-1995. SERGI, Gianluca. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20344/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20344/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University jj Learning and IT Services j O U x r- U u II I Adsetts Centre City Campus j Sheffield Hallam 1 Sheffield si-iwe Author: ‘3£fsC j> / j Title: ^ D o ltiu £ r a ' o UJTvd 4 c\ ^ £5ori CuCN^YTNCa IQ IO - Degree: p p / D - Year: Q^OO2- Copyright Declaration I recognise that the copyright in this thesis belongs to the author. I undertake not to publish either the whole or any part of it, or make a copy of the whole or any substantial part of it, without the consent of the author. I also undertake not to quote or make use of any information from this thesis without making acknowledgement to the author. Readers consulting this thesis are required to sign their name below to show they recognise the copyright declaration. They are also required to give their permanent address and date.