Goodbye Blue Sky: the Second World War in Pink Floyd's the Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

The First Major Exhibition of Stage Designs by Celebrated Cartoonist Gerald Scarfe

Gerald Scarfe: Stage and Screen At House of Illustration’s Main Gallery 22 September 2017 – 21 January 2018 The first major exhibition of stage designs by celebrated cartoonist Gerald Scarfe “I always want to bring my creations to life – to bring them off the page and give them flesh and blood, movement and drama.” – Gerald Scarfe "There is more to him than journalism... his elegantly grotesque, ferocious style remains instantly recognisable" – Evening Standard feature 20/09/17 Critics Choice – Financial Times 16/09/17 On 22 September 2017 House of Illustration opened the first major show of Gerald Scarfe’s striking production designs for theatre, rock, opera, ballet and film, many of which are being publicly exhibited for the very first time. Gerald Scarfe is the UK’s most celebrated political cartoonist; his 50-year-long career at The Sunday Times revealed an imagination that is acerbic, explosive and unmistakable. But less well known is Scarfe’s lifelong contribution to the performing arts and his hugely significant work beyond the page, designing some of the most high-profile productions of the last 30 years. This exhibition is the first to explore Scarfe’s extraordinary work for stage and screen. It features over 100 works including preliminary sketches, storyboards, set designs, photographs, ephemera and costumes from productions including Orpheus in the Underworld at English National Opera, The Nutcracker by English National Ballet and Los Angeles Opera’s The Magic Flute. It also shows his 1994 work as the only ever external Production Designer for Disney, for their feature film Hercules, as well as his concept, character and animation designs for Pink Floyd’s 1982 film adaptation of The Wall. -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

RICHARD STATE Final Edit

THE LONESOME VOYAGER Songs and stories from the Best Years of Our Lives STATE THEATRE – SYDNEY - SATURDAY AUGUST 15 Bookings: www.ticketmaster.com.au PHONE 136 100 Tickets on Sale at 10.00am Thursday April 30 On August 15th 2015, Richard Clapton makes a welcome return to Sydney’s State Theatre to continue the tradition of his annual concert in this special venue. This unique show will be performed in two parts. The first part of the show will be Richard and the masterful Danny Spencer on guitar, performing an acoustic repertoire and insights into Richard’s life and songwriting. Danny and Richard have been musical partners for well over a decade and Danny has become a well established part of Richard’s musical DNA. After interval, Richard returns to the stage with his full band and an exciting creative sound and lighting production. After more than 40 years of treading the boards on the Australian rock scene, this year Richard will bring together a very different style of show for the State Theatre. With the fantastic response to Richard’s recent memoirs, “The Best Years of Our Lives” in 2015, it occurred to him that audiences might just would appreciate a hybrid show featuring not just the music, but all the often crazy and often emotional stories behind the music. The book covers the halcyon years from the late Sixties in London to the Seventies and Eighties on the Oz rock scene. The musical journey onstage will cover those days of “The Golden Age” the likes of which we will never see again, accompanied by storytelling from one of the true survivors of those times. -

Cold Chisel to Roll out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History!

Cold Chisel to Roll Out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History! 56 New and Rare Recordings and 3 Hours of Previously Unreleased Live Video Footage to be Unveiled! Sydney, Australia - Under total media embargo until 4.00pm EST, Monday, 27 June, 2011 --------------------------------------------------------------- 22 July, 2011 will be a memorable day for Cold Chisel fans. After two years of exhaustively excavating the band's archives, 22 July will see both the first- ever digital release of Cold Chisel’s classic catalogue as well as brand new deluxe reissues of all of their CDs. All of the band's music has been remastered so the sound quality is better than ever and state of the art CD packaging has restored the original LP visuals. In addition, the releases will also include previously unseen photos and liner notes. Most importantly, these releases will unleash a motherlode of previously unreleased sound and vision by this classic Australian band. Cold Chisel is without peer in the history of Australian music. It’s therefore only fitting that this reissue program is equally peerless. While many major international artists have revamped their classic works for the 21st century, no Australian artist has ever prepared such a significant roll out of their catalogue as this, with its specialised focus on the digital platform and the traditional CD platform. The digital release includes 56 Cold Chisel recordings that have either never been released or have not been available for more than 15 years. These include: A “Live At -

What Shall We Do Now? Pdf Free Download

WHAT SHALL WE DO NOW? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy Canfield Fisher | 304 pages | 02 Sep 2017 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781975854263 | English | none What Shall We Do Now? PDF Book Contributed by T. What shall we do for wives for those who are left, since we have sworn by the LORD that we will not give them any of our daughters for wives? David Gagne. Shall we get into fights? Related 0. From the election to the pandemic, all atop systemic injustice continuing to manifest itself in many areas of our society. Message calling all believers to action; to move forward in servitude and stop delaying. It's not something that we need to take it without we taking likely you may have lost your finances. Don't Leave Me Now 6. Sixteenth, A man of God said, do not be afraid and that is what I'm coming to share with us this afternoon. The World's Greatest Pi…. That's a great promise. Vera SmartHumanism: it's all about making sure your tense matches what you are trying to say. Leave a Reply Want to join the discussion? We shall never still any of your glory will give them completely back to you for you deserve them all in the name of Jesus Christ, our Lord, Amen and Amen and Amen. Fathers Against Irrational Reasoning. Yes No. Hey You Two flowers — one phallic, the other yonic — timidly dance around each other before copulating for lack of a more discrete word , morphing from humanistic figures to animalistic creatures. Speak out, speak louder. -

2015 - 2016 Chairman's Manual

THE AMERICAN LEGION Department of Florida 2015 - 2016 CHAIRMAN'S MANUAL Table of Contents Foreword ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Director's Message ........................................................................................................................................ 3 District Chairmen List ................................................................................................................................... 4 What is Boys State? ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Important Dates to Remember ...................................................................................................................... 6 Overview of Chairman Responsibilities ....................................................................................................... 7 Delegate Fee.................................................................................................................................................. 8 Quota and Over-Quotas ................................................................................................................................ 9 Submitting Post Checks .............................................................................................................................. 10 Selection Process ....................................................................................................................................... -

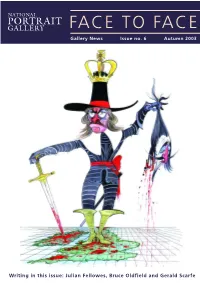

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Scarfe the Wall Live Tour Group.Pages

THE ART OF FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL PRESENTED BY ROGER WATERS THE WALL LIVE TOUR ARTWORK CATALOGUE THE ART OF GERALD SCARFE - FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC Image © Gerald Scarfe Image © Gerald Scarfe Roger Waters, c.2010 The Mother, c.2010 Pen, Ink & Watercolour on Paper Pen, Ink & Watercolour on Paper 33” x 23 ¼” sheet size 32” x 22 ¾” sheet size This illustration of Roger Waters on his The Wall Live A recent concept design, done for Roger Water’s tour (2010-2013) appeared on the front cover of The Wall Live tour (2010-2013) that was based on a Billboard Magazine 24 July, 2012. similar scene in the flm shown during the song The Trial where The Mother morphs into a giant protective wall surrounding a baby Pink. 458 GEARY STREET • SAN FRANCISCO CA 94102 • sfae.com • 415.441.8840 main THE ART OF GERALD SCARFE - FROM PINK FLOYD THE WALL SAN FRANCISCO ART EXCHANGE LLC Image © Gerald Scarfe Crazy Toys in the Attic, c.2010 Watercolor, Pen & Ink Collage on Paper 23 ¼” x 33” sheet size Image © Gerald Scarfe Go On Judge, Shit on Him! c.2010 This drawing is based on a segment of the animated scene of The Trial in The Wall flm. As the line “Crazy…Toys in the Pen, Ink & Watercolour on Paper Attic, I am crazy” is sung, the viewer sees a terrifed Pink 32 ½” x 22 ½” sheet size fade to grey as the camera zooms in on his eye until the scene fades into the next animation sequence. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

David Gilmour – the Voice and Guitar of Pink Floyd – “On an Island” and in Concert on the Big Screen for One Night Only

DAVID GILMOUR – THE VOICE AND GUITAR OF PINK FLOYD – “ON AN ISLAND” AND IN CONCERT ON THE BIG SCREEN FOR ONE NIGHT ONLY Big Screen Concerts sm and Network LIVE Present David Gilmour’s Tour Kick-Off Show Recorded Live In London On March 7 th , Plus an Interview and New Music Video, In More Than 100 Movie Theatres Across the Country (New York, NY – May 10, 2006) – David Gilmour, legendary guitarist and voice of Pink Floyd, will give American fans one more chance to catch his latest tour on the Big Screen on Tuesday, May 16th at 8:00pm local time. This exciting one-night-only Big Screen Concerts sm and Network LIVE event features David Gilmour’s March 7, 2006 performance recorded live at the Mermaid Theatre in London. Show highlights include the first public performance of tracks from On An Island , Gilmour’s new album, plus many Pink Floyd classics. David Gilmour played only 10 sold-out North American dates before returning to Europe, so this will be the only chance for many in the U.S. to see him in concert this year. This special event will also include an on-screen interview with David Gilmour talking about the creation of the new album, as well as the new On An Island music video. “We had a great time touring the U.S. and I’m glad that more of the fans will be able to see the show because of this initiative,” said David Gilmour DAVID GILMOUR: ON AN ISLAND will be presented by National CineMedia and Network LIVE in High-Definition and cinema surround sound at more than 100 participating Regal, United Artists, Edwards, Cinemark, AMC and Georgia Theatre Company movie theatres across the country.