The Scented Garden 1J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banksia Vincentia (Proteaceae), a New Species Known from Fourteen Plants from South-Eastern New South Wales, Australia

Phytotaxa 163 (5): 269–286 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.163.5.3 Could this be Australia’s rarest Banksia? Banksia vincentia (Proteaceae), a new species known from fourteen plants from south-eastern New South Wales, Australia MARGARET L. STIMPSON1, JEREMY J. BRUHL1 & PETER H. WESTON2 1 Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351 Australia Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] 2 National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, Mrs Macquaries Road, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia Abstract Possession of hooked, distinctively discolorous styles, a broadly flabellate common bract subtending each flower pair, and a lignotuber place a putative new species, Banksia sp. Jervis Bay, in the B. spinulosa complex. Phenetic analysis of individuals from all named taxa in the B. spinulosa complex, including B. sp. Jervis Bay, based on leaf, floral, seed and bract characters support recognition of this species, which is described here as Banksia vincentia M.L.Stimpson & P.H.Weston. Known only from fourteen individuals, B. vincentia is distinguished by its semi-prostrate habit, with basally prostrate, distally ascending branches from the lignotuber, and distinctive perianth colouring. Its geographical location and ecological niche also separate it from its most similar congeners. Introduction The Banksia spinulosa complex has a complicated taxonomic history (Table 1). Smith (1793) first described and named B. spinulosa Sm., and subsequent botanists named two close relatives, B. collina R.Br. and B. -

The Art of Making Perfume Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ART OF MAKING PERFUME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rebecca Park Totilo | 116 pages | 31 May 2010 | Rebecca at the Well Foundation | 9780982726419 | English | United Kingdom The Art of Making Perfume PDF Book However, differences in organic synthesis may result in minute differences in concentration of impurities. For other uses, see Perfume disambiguation. Perfume manufacture in Russia grew after and became globally significant by the early 20th century. In early America, the first scents were colognes and scented water by French explorers in New France. April An opened bottle will keep its aroma intact for several years, as long as it is well stored. In , [6] archaeologists uncovered what are believed [ by whom? Roman perfume bottle; 1st century AD; glass; 5. This is because of the Muslim movement to Europe. Enchanting, Gifted, Beautiful, A work of art, are words used by readers to describe this book. Ancient Greek perfume bottle in shape of an athlete binding a victory ribbon around his head; circa s BC; Ancient Agora Museum Athens. As such there is significant interest in producing a perfume formulation that people will find aesthetically pleasing. Xlibris Corporation. Beck; S. The book discuss the nature of almost different spirits See also: Alchemy and chemistry in Islam. Related Searches. The notes unfold over time, with the immediate impression of the top note leading to the deeper middle notes, and the base notes gradually appearing as the final stage. Florida water, an uncomplicated mixture of eau de cologne with a dash of oil of cloves, cassia and lemongrass, was popular. Platts-Mills; Johannes Ring The art of perfumery prospered in Renaissance Italy , and in the 16th century, Italian refinements were taken to France by Catherine de' Medici 's personal perfumer, Rene le Florentin. -

Timeline / 1810 to 1930

Timeline / 1810 to 1930 Date Country Theme 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts Buildings present innovation in their architecture, decoration and positioning. Palaces, patrician houses and mosques incorporate elements of Baroque style; new European techniques and decorative touches that recall Italian arts are evident at the same time as the increased use of foreign labour. 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts A new lifestyle develops in the luxurious mansions inside the medina and also in the large properties of the surrounding area. Mirrors and consoles, chandeliers from Venice etc., are set alongside Spanish-North African furniture. All manner of interior items, as well as women’s clothing and jewellery, experience the same mutations. 1810 - 1830 Tunisia Economy And Trade Situated at the confluence of the seas of the Mediterranean, Tunis is seen as a great commercial city that many of her neighbours fear. Food and luxury goods are in abundance and considerable fortunes are created through international trade and the trade-race at sea. 1810 - 1845 Tunisia Migrations Taking advantage of treaties known as Capitulations an increasing number of Europeans arrive to seek their fortune in the commerce and industry of the regency, in particular the Leghorn Jews, Italians and Maltese. 1810 - 1850 Tunisia Migrations Important increase in the arrival of black slaves. The slave market is supplied by seasonal caravans and the Fezzan from Ghadames and the sub-Saharan region in general. 1810 - 1930 Tunisia Migrations The end of the race in the Mediterranean. For over 200 years the Regency of Tunis saw many free or enslaved Christians arrive from all over the Mediterranean Basin. -

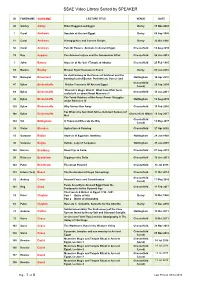

SSAE Video Library Sorted by SPEAKER

SSAE Video Library Sorted by SPEAKER ID FORENAME SURNAME LECTURE TITLE VENUE DATE 40 Shirley Addey Rider Haggard and Egypt Derby 15 Nov 2003 7 Carol Andrews Amulets of Ancient Egypt Derby 09 Sep 1995 11 Carol Andrews Hieroglyphics and Cursive Scripts Derby 12 Oct 1996 56 Carol Andrews Pets Or Powers: Animals In Ancient Egypt Chesterfield 14 Aug 2010 78 Ray Aspden The Armana Letters and the Dahamunzu Affair Chesterfield 06 Jun 2012 3 John Baines Aspects of the Seti I Temple at Abydos Chesterfield 25 Feb 1995 53 Marsia Bealby Minoan Style Frescoes in Avaris Derby 05 Jun 2010 He shall belong to the flames of Sekhmet and the 153 Maragret Beaumont Nottingham 14 Apr 2018 burning heat of Bastet: Punishment, Curses and Threat Formulae in Ancient Egypt. Chesterfield 47 Dylan Bickerstaffe Hidden Treasures Of Ancient Egypt 28 Sep 2009 (Local) ‘Pharoah’s Magic Wand? What have DNA Tests 68 Dylan Bickerstaffe Chesterfield 13 Jun 2011 really told us about Royal Mummies?’ The Tomb-Robbers of No-Amun:Power Struggles 98 Dylan Bickerstaffe Nottingham 10 Aug 2013 under Rameses IX 129 Dylan Bickerstaffe Why Sinhue Ran Away Chesterfield 13 Feb 2016 For Whom the Sun Doth Shine, Nefertari Beloved of 148 Dylan Bickerstaffe Chesterfield (Main) 16 Sep 2017 Mut Chesterfield 143 Val Billingham A Thousand Miles Up the Nile 13 May 2017 (Local) 33 Victor Blunden Agriculture & Farming Chesterfield 27 Apr 2002 15 Suzanne Bojtos Aspects of Egyptian Jewellery Nottingham 24 Jan 1998 36 Suzanne Bojtos Hathor, Lady of Turquoise Nottingham 25 Jan 2003 100 Karren Bradbury Road -

Egyptian Gardens

Studia Antiqua Volume 6 Number 1 Article 5 June 2008 Egyptian Gardens Alison Daines Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Daines, Alison. "Egyptian Gardens." Studia Antiqua 6, no. 1 (2008). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ studiaantiqua/vol6/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Egyptian Gardens Alison Daines he gardens of ancient Egypt were an integral component of their religion Tand surroundings. The gardens cannot be excavated like buildings and tombs can be, but archeological relics remain that have helped determine their construction, function, and symbolism. Along with these excavation reports, representations of gardens and plants in painting and text are available (fig. 1).1 These portrayals were frequently located on tomb and temple walls. Assuming these representations were based on reality, the gardens must have truly been spectacular. Since the evidence of gardens on excavation sites often matches wall paintings, scholars are able to learn a lot about their purpose.2 Unfortunately, despite these resources, it is still difficult to wholly understand the arrangement and significance of the gardens. In 1947, Marie-Louise Buhl published important research on the symbol- ism of local vegetation. She drew conclusions about tree cults and the specific deity that each plant or tree represented. In 1994 Alix Wilkinson published an article on the symbolism and forma- tion of the gardens, and in 1998 published a book on the same subject. -

Current Chemistry Letters Analysis of Selected Allergens Present In

Current Chemistry Letters 10 (2021) 435–444 Contents lists available at GrowingScience Current Chemistry Letters homepage: www.GrowingScience.com Analysis of selected allergens present in alcohol-based perfumes Anna Łętochaa* and Rafał Rachwalika aFaculty of Chemical Engineering and Technology, Cracow University of Technology, Warszawska 24, 31-155 Kraków, Poland C H R O N I C L E A B S T R A C T Article history: The aim of the research was to analyse fragrance allergens in selected alcohol-based perfumery Received February 18, 2021 products with the application of gas chromatography. Toilet waters and scented waters were Received in revised form analysed. Samples of the selected perfumery products were tested for the presence of typical April 25, 2021 allergens, such as linalool, citral, citronellol, geraniol, eugenol and alpha-isomethyl ionone, in Accepted May 7, 2021 the so-called fragrance concentrate. The obtained results showed that each of the products Available online contained at least a few of the above-mentioned allergens. Nevertheless, the majority of the May 7, 2021 analysed products satisfied the recommendations of the Scientific Committee on Cosmetic Keywords: Products and Non-food Products valid for cosmetics intended to remain on the skin for some Perfumery products Fragrance substances time. Allergens IFRA Standards Gas chromatography © 2021 Growing Science Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Depending on the content of the fragrance composition and ethyl alcohol, perfumery products can be divided into: parfum (perfume), eau de parfum (scented water), eau de toilette (toilet water), eau de Cologne (cologne) and eau de fraiche (body splash, body spray, body mist or body spritz). -

Guide to the Nursery and Seed Trade Catalogues, 1832-1999 Page 4 of 69

Guide to the Nursery and Seed Trade Catalogues, 1832-1999 Page 4 of 69 Series Outline 1. Nursery and Seed Trade Catalogues, 1832-1999 2. Bound Volumes: A Collection of Seed and Plant Catalogues for the United States, 1940 Special Collections, The Valley Library PDF Created November 13, 2015 Guide to the Nursery and Seed Trade Catalogues, 1832-1999 Page 6 of 69 Detailed Description of the Collection Box 1. Nursery and Seed Trade Catalogues, 1832-1999 1 Nursery and Seed Trade Catalogues (Bound), 1800-1899 Folder 0000.001 Rare Cacti. A. Blanc & Co. Philadelphia, PA., undated 0000.002 New and Rare Plants and Bulbs. A. Blanc & Co. Philadelphia, PA., undated 0000.017 Catalogue of Water Lilies, Nelumbiums, and Other New and Rare Aquatics. Benjamin Grey. Malden, MA., undated 1874.001 Hortus Krelageanus. Allgemeines Beschreibendes und Illustrirtes Verzeichniss. E. H. Krelage & Son. Haarlem, Netherlands., September 1874 (Not in English) 1874.002 A General Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Horticultural Establishment. E. H. Krelage & Son. Haarlem, Netherlands., November 1874 1884.001 Prijs-Courant der Hyancinthen voor Tentoonstelling. E. H. Krelage & Son. Haarlem, Netherlands., April 1884 1885.001 Rare Lilies. Edmund Sturtevant. Bordentown, NJ., 1885 (rare water lilies) 1886.002 Descriptive Catalogue of Choice New and Old Chrysanthemums. E. Fewkes & Sons. Newton Highlands, MA., Spring 1886 1887.001 Wholesale Catalogue of Horticultural Establishment; No. 394a. E. H. Krelage & Son. Haarlem, Netherlands., 1887-1888 (American Edition) 1888.001 Wholesale Catalogue of the Horticultural Establishment. E. H. Krelage & Son. Haarlem, Netherlands., 1888-1889 (American Edition) 1888.002 Catalogue of Miscellaneous Bulbous- and Tuberous-Rooted Plants. -

Plant Lists, a Common Sense Guide

Plant Lista common sense guide Careful plant selection is the key to creating a healthy and easy to maintain landscape. This guide will help you choose plants adapted to the Northwest. Plants on this list are either low-water use, resistant to insects and diseases or native to western Washington. Many Northwest gardens include non-native and native plants, which provide the gardens with beautiful foliage, patterns and textures. This guide also highlights plants selected by the Great Plant Picks program by using a leaf symbol. Great Plant Picks is a regional plant awards program designed to help the home gardener identify unbeatable plants for maritime Pacific Northwest gardens. It is sponsored by the Elizabeth C. Miller Botanical Garden. For more information visit www.greatplantpicks.org. Every time you plant, fertilize, water or control pests in your garden, choose methods that protect your pets and your family’s health. Ground Covers (E) Evergreen (D) Deciduous COMMON NAME *LOW EXPOSURE REMARKS SCIENTIFIC NAME WATER USE Ajuga No Part Shade (E) One of the best known and Ajuga reptans most useful ground covers; fast growing; blue flowers in spring Creeping Oregon Grape Yes Part Shade, (E) Native; yellow spring flowers and blue Receive a free Mahonia repens Sun berries; attracts birds e-newsletter with helpful tips on Cotoneaster Yes Sun (E/D) Good for erosion control, spring home and garden Cotoneaster (all varieties) bloom; small pink flowers care! False Lily-of-the-Valley Yes Shade, (D) Native; aggressive; good for wood- To subscribe: -

California Native Plants for Your Garden °

California Native Plants for Your Garden ° Botanical Name Common Name Life Form C = coast C = I = inland sun shade shade part drought summer Needs water OK sprinkler sand clay heat inland cold to 25 or dies decidous back Acer macrophyllum Big Leaf Maple Tree I * * * * * * * Acer negundo California Box Elder Small Tree I C * * * * * * * * Achillea millefolium Yarrow Ground Cover I C * * * * * * * * * * Acmispon glaber (Lotus Deerweed Small Shrub scoparius) C * * * * * Adenostoma Chamise Shrub I * * * * * * fasciculatum Aesculus californica California Buckeye Tree I C * * * * * * * * Aquilegia formosa Western Columbine Herb I C * * * * * * * * Arbutus menziesii Madrone Tree C I * * * * * * * * * Arctostaphylos 'Dr. Manzanita Tree-like C * * * * Arctostaphylos 'Howard Manzanita Shrub C I * * * * * * * Arctostaphylos Manzanita Shrub I C * * * * * * * Arctostaphylos Manzanita Low Shrub C I * * * * * * Arctostaphylos edmunsii Manzanita Low Shrub C I * * * * * Arctostaphylos 'Emerald Manzanita Gound Cover C I * * * * * Arctostaphylos hookeri Manzanita Gound Cover C * * * * * * * Arctostaphylos hookeri Manzanita Shrub C * * * * * * * Arctostaphylos 'Indian Manzanita Shrub C * * * * * * Arctostaphylos 'Louis Manzanita Shrub I * * * * * * * * * Arctostaphylos pumila Manzanita Ground Cover I * * * * * * * Arctostaphylos rudis Manzanita Shrub C * * * * * * Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Manzanita Gound Cover C * * * * * Armeria maritima Thrift Ground Cover I C * * * * * * Artemisia californica California Sagebrush Shrub I C * * * * * * * * Artemisia douglasiana -

Lesson 4 Designing a Wildlife Garden

Lesson 4: Design a Wildlife Garden Teaching Instructions Learning Outcomes • Communicate: take part in conversation, share ideas and information. • Improve their understanding of the needs of living organisms, conservation and biodiversity. • Explore ways to represent ideas and information as a plan. • Outdoor teaching provides a real-world context for learning, supports emotional and physical well-being, impacts positively on self-esteem and increases knowledge of and care for the natural environment. Required Resources Plain paper (A3 or larger) Coloured pencils, felt pens Access to computers and the internet for researching wildlife gardens. Preparation Arrange the desks for group work (2-4 people per group) Notes Lesson duration: We would recommend spending 120 – 180 minutes. You may want to split the activities into a series of lessons. * Buglife has provided notes, at the end of this lesson, to help you with the essential features of a wildlife garden. 1 Lesson 4: Design a Wildlife Garden Teaching Instructions Teaching Plan Activity 1 - Discussion Start the lesson by asking the children what we mean by a wildlife garden. Can a conventional garden be a wildlife garden? Why do we need to create wildlife gardens? (natural habitats declining). What wildlife would use the garden? What would the wildlife require from the garden? Food, water, shelter – and how would the features of the garden meet these needs? Activity 2 - Design a Wildlife Garden Ask the children to research what makes a good wildlife garden using books and the internet and to discuss, in their groups, what they want to include in their garden. Will it be solely for wildlife or will they include elements for the humans as well? They should then make a plan of the garden, labelling the different features. -

Making Room for Native Pollinators How to Create Habitat for Pollinator Insects on Golf Courses by Matthew Shepherd, the Xerces Society

Making Room for Native Pollinators How to Create Habitat for Pollinator Insects on Golf Courses by Matthew Shepherd, The Xerces Society Making Room for Native Pollinators How to Create Habitat for Pollinator Insects on Golf Courses Matthew Shepherd Pollinator Program Director, The Xerces Society Copyright© 2002 By THE UNITED STATES GOLF ASSOCIATION AND THE XERCES SOCIETY All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Recycled Paper Cover: Flower-flies, like this drone fly, are often mistaken for bees. They play an important role as a pollinator. Photo Credits: Cover and page 10 — James Cane Pages three and four — Edward S. Ross Remaining photos — The Xerces Society and USGA M AKING R OOM F OR N ATIVE P OLLINATORS Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Pollinators, the Forgotten Link in the Chain of Life................................................................................... 3 Bees, the dominant pollinators ......................................................................................................................... 3 The threats bees face ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Gentle pollinators................................................................................................................................................... 4 The Natural -

Garden Events

DESIGN SPECIFICATIONS Call for applications GARDEN EVENTS 2021 Listed as a “Historic Monument” (Monument Historique) and recognised as a “Remarkable Garden” (Jardin Remarquable) in 2005, Wesserling Park is testimony to an extraordinary textile adventure in a valley of the River Thur in the Upper Vosges. This unique site is a former “Royal Textile Printing Factory” with an incredible number of preserved buildings linked to the textile industry. The gardens have been landscaped ever since the site was first managed and the château was built. They were originally created as ornamental gardens for the enjoyment of captains of industry, bearing witness to the landscaping conventions of the various centuries. Later they were steadily turned into vegetable gardens for workers, and then abandoned, before being gradually restored. Each year for almost 18 years, designers, visual artists and landscapists have brought life to these gardens, producing temporary creations which surprise, question and enchant summer visitors. Over the past two springs, professional and amateur photographers have opened our eyes to the world with their emotionally charged photos. For this new season, we would like to offer a triple view of the site through: - a spring photo exhibition, - plastic installations ready at the opening, - and the perpetuation of our Festival des Jardins Métissés (mixed gardens Festival) during the whole summer period. Once again this year, you are offered a new theme. It again focuses on highlighting the site’s values, between respect for the past and innovation, putting the emphasis on heritage and offering interactive games for our visitors, new artistic creations and sustainable development.