Connections Between Voice and Design in Puppetry: a Case-Study" (2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Happytime Murders” by Helen Lutz

“The Happytime Murders” By Helen Lutz As we go along the journey of life, we find many things which just shouldn’t be but happen every day. The anonymous bullying of a school child – shouldn’t be, but is. Guns freely being made on 3-D printers – shouldn’t be, but are. Muppets spouting profanities and having raucous sex – shouldn’t be, but is in the new movie “The Happytime Murders.” Los Angeles – sometime in the future ... People co-exist with puppets, however, puppets are definitely second class citizens. Phil Phillips, a blue skinned, chimney smoking, alcoholic private investigator puppet (Bill Barretta) opens the movie with an old Jack Webb “Dragnet” style narration of another day in the city. Phillips, the only puppet to have once been a police officer, now works various puppet cases after being part of a fatal mishap. Approached by a seductive Sandra puppet hoping that Phil will take her mysterious, nymphomania case, leads Phil to a puppet porn shop (it would be nice to un-see the action between the cow and octopus). A robbery gone wrong while Phil is in the back looking at store files, leads to a deadly scene – stuffing everywhere – enter the police and Phil’s old partner Detective Connie Edwards (Melissa McCarthy). There’s obviously no love lost between the two. Phil knows the owner of the puppet sex shop from the good old days when he starred with Phil’s brother in a popular 80’s kids’ show “The Happytime Gang.” Life after the show has gone downhill for most of the cast. -

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

Download This Issue (PDF)

CONTENTS: From the Editors The only local voice for news, arts, and culture. 200 issues in and counting Editors-in-Chief: August 29, 2018 Brian Graham & Adam Welsh ournalism will kill you,” Horace Greeley once said, “but it will Managing Editor: Nick Warren Hiding In Plain Sight – 5 “J keep you alive while you’re at it.” Though the quote is well over a century Copy Editor: Matt Swanseger Another sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic old, it’s still true today. In fact, we used it Contributing Editors: Church leads to horror and exasperation to open the introduction to our 100th is- Ben Speggen sue in 2014. It’s our 200th issue now, and Jim Wertz Company G’s World War I Disaster – 8 we’re very much alive. Contributors: Greeley of course, is well known to any Maitham Basha-Agha One hundred years ago this month journalism student. And any Erie histori- Mary Birdsong an worth their salt knows that he spent a Charles Brown Jonathan Burdick VN6: An Appeal to the Ethical Voter – 10 stint of time here in town working for the Tracy Geibel Erie Gazette. Jonathan Burdick certainly Lisa Gensheimer Pushing a button to restore decency to democracy knows this, and is quick to bring up Gree- Miriam Lamey ley’s contributions and thoughts on his Tommy Link on November 6 Aaron Mook time in Erie. Burdick traces the roots of Dan Schank Two Centuries of Making Headlines – 13 Erie newspapers, from The Mirror in 1811, Tommy Shannon all the way to what you’re reading right Ryan Smith now. -

Muppets Now Fact Sheet As of 6.22

“Muppets Now” is The Muppets Studio’s first unscripted series and first original series for Disney+. In the six- episode season, Scooter rushes to make his delivery deadlines and upload the brand-new Muppet series for streaming. They are due now, and he’ll need to navigate whatever obstacles, distractions, and complications the rest of the Muppet gang throws at him. Overflowing with spontaneous lunacy, surprising guest stars and more frogs, pigs, bears (and whatevers) than legally allowed, the Muppets cut loose in “Muppets Now” with the kind of startling silliness and chaotic fun that made them famous. From zany experiments with Dr. Bunsen Honeydew and Beaker to lifestyle tips from the fabulous Miss Piggy, each episode is packed with hilarious segments, hosted by the Muppets showcasing what the Muppets do best. Produced by The Muppets Studio and Soapbox Films, “Muppets Now” premieres Friday, July 31, streaming only on Disney+. Title: “Muppets Now” Category: Unscripted Series Episodes: 6 U.S. Premiere: Friday, July 31 New Episodes: Every Friday Muppet Performers: Dave Goelz Matt Vogel Bill Barretta David Rudman Eric Jacobson Peter Linz 1 6/22/20 Additional Performers: Julianne Buescher Mike Quinn Directed by: Bill Barretta Rufus Scot Church Chris Alender Executive Producers: Andrew Williams Bill Barretta Sabrina Wind Production Company: The Muppets Studio Soapbox Films Social Media: facebook.com/disneyplus twitter.com/disneyplus instagram.com/disneyplus facebook.com/muppets twitter.com/themuppets instagram.com/themuppets #DisneyPlus #MuppetsNow Media Contacts: Disney+: Scott Slesinger Ashley Knox [email protected] [email protected] The Muppets Studio: Debra Kohl David Gill [email protected] [email protected] 2 6/22/20 . -

Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Episode Guide Episodes 001–051

Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Episode Guide Episodes 001–051 Last episode aired Friday January 25, 2019 www.netflix.com c c 2019 www.tv.com c 2019 www.netflix.com c 2019 c 2019 telltaletv.com movienewsguide.com c 2019 www.ew.com c 2019 showsnob.com The summaries and recaps of all the Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http://www.netflix.com and http://movienewsguide.com and http://telltaletv.com and http://www.ew. com and http://showsnob.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on February 6, 2019 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.61 Contents Season 1 1 1 Kimmy Goes Outside! . .3 2 Kimmy Gets a Job! . .5 3 Kimmy Goes on a Date! . .7 4 Kimmy Goes to the Doctor! . .9 5 Kimmy Kisses a Boy! . 11 6 Kimmy Goes to School! . 13 7 Kimmy Goes to a Party! . 15 8 Kimmy Is Bad at Math! . 17 9 Kimmy Has a Birthday! . 19 10 Kimmy’s in a Love Triangle! . 21 11 Kimmy Rides a Bike! . 23 12 Kimmy Goes to Court! . 25 13 Kimmy Makes Waffles! . 27 Season 2 29 1 Kimmy Goes Roller Skating! . 31 2 Kimmy Goes on a Playdate! . 33 3 Kimmy Goes to a Play! . 35 4 Kimmy Kidnaps Gretchen! . 37 5 Kimmy Gives Up! . 39 6 Kimmy Drives a Car! . 41 7 Kimmy Walks Into a Bar! . 43 8 Kimmy Goes to a Hotel! . -

11 Schreiber Is a Great School, but It Suffocates Your Life and Is Increasingly Stressful, Said Unior Nathan Lefcowitz

2 THE SCHREIBER TIMES NEWS FRIDAY, DECEMBER 23, 2011 I N THIS ISSUE... ! e Schreiber Times N!"#. Editors-in-Chief Senior Experience p. 3 Katya Barrett Broadway assembly p. 4 Sophia Ja. e MSG Varsity p. 6 Copy Editors Matt Heiden O$%&%'&#. Will Zhou Gi( -giving p. 8 Bus issues p. 9 News Cooking p. 9 Editor Hannah Fagen Assistant Editors F!)*+,!#. Minah Kim Describing Schreiber p. 11 Celine Sze Teachers’ Lounge p. 14 Frozen yogurt p. 15 Opinions Editors Alice Chou A-E. Brendan Weintraub Best of 2011 p. 17 Assistant Editor ! e Muppets p. 18 Jake Eisenberg Amy Winehouse p. 20 Features Editor S$',*#. Hannah Zweig Gymnastics p. 21 Assistant Editors Sports media p. 22 David Katz Bowling p. 23 Heidi Shin A&E Senior Jessica Yang took this photo during summer vacation in the Catskill Mountains. Editor After a storm, the sky cleared allowing her to take a photograph of the mountains. Her Bethia Kwak photographs were on display for the AP Photography and 2D Design exhibit on Dec. 14. Assistant Editors Katie Fishbin N EWS BRIEFS Kerim Kivrak Upstander of the Month emails to members of Congress in attempt the sirens,” said junior Lani Hack. Sports Junior Christianne Bharath was to repeal Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and / e A( er a few minutes, the local 0 re Senior Editors recently featured on the website of the Defense of Marriage Act.s department arrived to survey the scene Brett Fishbin Holocaust Memorial & Tolerance Center “Schreiber is home to many di. erent and determine the cause of the smoke Drew Friedman of Nassau County as “Upstander of the people, and each and every one should alarms. -

Bill Barretta

This transcript was exported on Aug 24, 2019 - view latest version here. Charlie Mechem: Hello and welcome to 15 Minutes with Charlie. I'm your host Charlie Mechem, and I want to help you communicate more effectively. And I think that the use of anecdotes can get you there. Explore this with me as I share anecdotes from my recently published book, Total Anecdotal, and ask guests to react in relation to their own experience and careers. My guest today is a talented family friend, Bill Barretta. Bill is an illustrious American puppeteer who has been performing with the Jim Henson Company since 1991. And this has earned him a position as one of the leading Muppet performers, and the producer of productions such as It's a Very Muppet Christmas Movie and the Muppet's Wizard of Oz. So please sit back and enjoy my 15 minutes with this very talented young man, Bill Barretta. Happy to have you, Bill. Bill Barretta: Oh well, come on. I mean, come on. Thank you. Charlie Mechem: Okay. The approach I like to use is to quote several anecdotes from my book, Total Anecdotal, and ask you to react as to how these might have played a part in your own life. Bill Barretta: Okay. Can I just say one thing? Charlie Mechem: And yes, of course. Bill Barretta: I just want you to know, actually, that obviously without you knowing, and without me realizing until much later, that you played an important part in my life growing up; helping and being a part of providing the entertainment that I [inaudible 00:01:57] and inspired to do, was create characters as a kid. -

EXHIBITS in the Main Gallery 12 THURSDAY 19 THURSDAY ANDREW HOLLANDER: Meet the Artist BOOK DISCUSSION GROUP: Townie, by Whose Work Is in the Photography Gallery

July 2012 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery 12 THURSDAY 19 THURSDAY ANDREW HOLLANDER: Meet the artist BOOK DISCUSSION GROUP: Townie, by whose work is in the Photography Gallery. Andre Dubus III, facilitated by Lee Fertitta. Reception 7:30 to 9 p.m. Story in this issue. 1:30 p.m. 3rdTHURSDAYS @ 3: Orientalism. The term “Orientalism” is used to define a group of Western artists who focus on the depiction of Eastern culture, and was a spe- cialty of 19th century academic art. Several FRIDAY Orientalist painters actually traveled great 13 distances, such as North Africa, to sketch SANDWICHED IN: Meet Andrew Kane. The Great Neck resident will read from “exotic” scenes. Delacroix, Gericault, and discuss Joshua, a Brooklyn Tale. This Ingres, Gerome are a few of the many gripping saga tells a story of racism, be- painters of this period who became known trayal and redemption. Books will be avail- for their depictions of scenes from faraway able for purchase and signing. 12:10 p.m. cultures. Eroticized harem scenes became very popular at this time. Join Ines Powell for an exploration of this genre. 3 p.m. AAC Aaron Morgans’s The Beige Gallery ART ADVISORY COUNCIL: Members of the library’s Art Advisory Council exhibit “The Library Through Our Eyes,” in celebration of the library’s 120th anniversary, throughout 27 FRIDAY the summer. SATURDAY SANDWICHED IN: Meet Alex Stone: Fool- In the Martin Vogel Photography Gallery 14 ing Houdini. When he was 5-years-old, NEXT CHAPTER: Join us for a discussion FRIDAY Alex Stone’s father bought him a magic ANDREW HOLLANDER: Photographs, July 6 through August 31. -

Sherlock Holmes Films

Checklist of Sherlock Holmes (and Holmes related) Films and Television Programs CATEGORY Sherlock Holmes has been a popular character from the earliest days of motion pictures. Writers and producers realized Canonical story (Based on one of the original 56 s that use of a deerstalker and magnifying lens was an easily recognized indication of a detective character. This has led to stories or 4 novels) many presentations of a comedic detective with Sherlockian mannerisms or props. Many writers have also had an Pastiche (Serious storyline but not canonical) p established character in a series use Holmes’s icons (the deerstalker and lens) in order to convey the fact that they are acting like a detective. Derivative (Based on someone from the original d Added since 1-25-2016 tales or a descendant) The listing has been split into subcategories to indicate the various cinema and television presentations of Holmes either Associated (Someone imitating Holmes or a a in straightforward stories or pastiches; as portrayals of someone with Holmes-like characteristics; or as parody or noncanonical character who has Holmes's comedic depictions. Almost all of the animation presentations are parodies or of characters with Holmes-like mannerisms during the episode) mannerisms and so that section has not been split into different subcategories. For further information see "Notes" at the Comedy/parody c end of the list. Not classified - Title Date Country Holmes Watson Production Co. Alternate titles and Notes Source(s) Page Movie Films - Serious Portrayals (Canonical and Pastiches) The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes 1905 * USA Gilbert M. Anderson ? --- The Vitagraph Co. -

Jake Bazel Resume 2021

SAG-AFTRA | [email protected] | 732.861.5533 FILM / TELEVISION SESAME STREET Assist Muppet Performer HBO & PBS/ Sesame Workshop Ep. 4605 “Funny Farm” dir. Joey Mazzarino Ep. 4611 “Abby’s Fairy Garden” dir. Ken Diego Ep. 4810 “The Last Straw” dir. Benjamin Lehmann 90th MACY’S THANKSGIVING DAY PARADE Muppet Performer NBC/ Muppets Studio (Disney) Muppets Opening Number dir. Alex Vietmeier, Bill Barretta SESAME STREET IN COMMUNITIES (Seasons 48, 49, 50) Assist Muppet Performer HBO & PBS/ Sesame Workshop Trauma Initiative (10 episodes) dir. Ken Diego Grow Up Great Initiative (5 episodes) dir. Matt Vogel Foster Care Initiative (5 episodes) dir. Ken Diego Military Caregiving Initiative (5 episodes) dir. Ken Diego HELPSTERS Ensemble Puppeteer Apple TV/ Sesame Workshop Ep. 126 “Trophy Todd” dir. Shannon Flynn ZivaKIDS MEDITATION COURSE (10 episodes) Z Bunny (Lead) dir. Susan Blackwell, Mark Dearborn 93rd MACY’S THANKSGIVING DAY PARADE Assist Muppet Performer NBC/ Sesame Workshop Sesame Street Opening Number dir. Alex Vietmeier, Matt Vogel CALIFORNIA LIVE Z Bunny (Appearance) NBC Los Angeles PUPPET REGIME! Lead Puppeteer PBS/ dir. Alex Klement CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES “WELCOME ABOARD” AD Lead Puppeteer Gables Grove/ dir. John Tartaglia SESAME STREET DIGITAL CONTENT (Season 51) Assist Muppet Performer Sesame Workshop/ dir. Todd E. James TONY THE TIGER 2019 CAMPAIGN (proof of concept) Digital LEAP Puppeteer (Lead) The Mill/ dir. Adam Carroll HPE IT MONSTER CAMPAIGN - HPE DISCOVER 2018 Digital LEAP Puppeteer (Lead) The Mill/ dir. Jeffrey Dates SANDRA BOYNTON’S FROG TROUBLE Bunny Puppeteer (Lead) Crazy Lake Pictures “End of a Summer Storm” (Alison Krauss) dir. Keith Boynton SOMEONE WROTE THAT SONG Utility Puppeteer Dramatists Guild/ Transient Pictures (w/ Alan Menken, Stephen Schwartz) dir. -

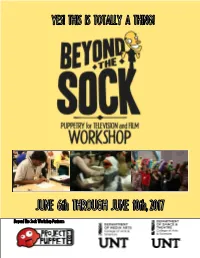

Beyond the Sock Workshop Partners: There’S a Method to Our Madness

Beyond The Sock Workshop Partners: There’s A Method To Our Madness. Beyond the Sock is an intensive, five day workshop focusing on puppetry performance in television and film. Attendees have the unique opportunity to learn the manipulation of hand and rod style puppets from two of the top performers in the industry, Peter Linz and Noel MacNeal. Attendees also learn the art of design and construction from master puppet builder Pasha Romanowski. Through a blend of small group instruction and hands on training puppet builders and performers of all skill levels can develop their skills, discover new techniques and learn to craft their own characters. Don’t miss the unique opportunity! Registration and Attendance Fees General Registration: Includes performance and building sessions, puppet building materials and welcome reception. Please note that all general $1400.00 registration attendees must pre-register. Student Registration: Must be a currently enrolled college or university student in good standing. Must provide proof of enrollment and $850.00 letter of recommendation. Contact us for more details. Student attendees Must be at least 18 years of age. Ready to get in on the action? All registrations must be completed electronically using a valid credit or debit card. Simply visit us online at www.beyondthesock.com at www.beyondthesock.unt.edu or sing up via direct link on our event registration page found at https://beyondthesock.eventbrite.com. Our class size is limited in order to maximize the experience for our attendees. Register today! WORKSHOP DATES: JUNE 6th through JUNE 10th, 2017 NEED MORE INFO? EMAIL: [email protected] Our Instructors Are Among The Best In The Business! Performance Instructors Peter Linz is a professional puppet performer who has performed in film, theatre and television using both hand-and-rod and full-body puppets. -

Misspiggy'sbackstoryandothermuppetsecrets

Living B5 SOUTH JERSEY TIMES, AFFILIATED WITH NJ.COM SUNDAY, MARCH 18, 2018 LeTRAVEL ssons from a first-timer 10 tips to make the most of an all-inclusive vacation Nicole Pensiero For South Jersey Times For as many times as I’d visited island destinations over the years, I’d always shied away from all-inclusive resorts, imag- ining long buffet lines, crowded swimming pools and watered-down drinks. Even when I heard rave reviews, I never seriously considered going the “full-package” route. But after floating the idea of a mid-win- ter getaway to a group of longtime friends to celebrate/escape a “milestone” birthday — mine — I found myself surprised when my Google search ultimately led me to an all-inclusive resort that proved not only a great value, but an amazing vacation expe- rience. We decided on a trip to the Mexican Caribbean for couple of reasons: half the group had never been “south of the border” and were eager to visit — and Mexico is a decidedly less expensive destination than some of the Eastern Caribbean islands — and even the Bahamas, for that matter. We could not have made a better choice. The resort we selected — the 4-star, 340-room Royal Sands, located smack- dab in the middle of Cancun’s coveted beachfront hotel zone – is one of six Mex- ican properties owned by Royal Resorts, founded in 1975 and considered a pioneer resort company in the Riviera Maya/Can- cun region and in the vacation ownership industry. The company, we soon learned, is extremely customer-focused.