Images of Christ in the Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L E N T E N P R O G R a M 2 0

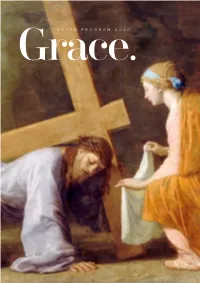

LENTEN PROGRAM 2020 Grace. 12 TheFIRST Temptation. SUNDAY OF LENT CONTENTS 22 The SECONDTransfiguration. SUNDAY OF LENT 4 Leading the weekly sessions 5 Contributor biographies Sunday reflections 32 Fr Christopher G Sarkis The Samaritan Sr Anastasia Reeves OP THIRD SUNDAYwoman. OF LENT Mgr Graham Schmitzer 6 Contributor biographies Weekday reflections 42 Sr Susanna Edmunds OP Healing the Fr Damian Ference blind man. Peter Gilmore FOURTH SUNDAY OF LENT Michael “Gomer” Gormley Sr Mary Helen Hill OP Fr Antony Jukes OFM Sr Elena Marie Piteo OP 53 Sr Magdalen Mather OSB Darren McDowell RaisingFIFTH SUNDAY Lazarus. OF LENT Trish McCarthy Matthew Ockinga Fr Chris Pietraszko Mother Hilda Scott OSB 62 Professor Eleonore Stump Michelle Vass ThePALM Passion. SUNDAY 74 HeEASTER is risen. SUNDAY 3 The Temptation.FIRST SUNDAY OF LENT 4 ARTWORK REFLECTION He was born of a poor family, and his mother had hoped he would become a priest. He was involved in the insurrection of 1848 which erupted in Naples. After his death, he was labelled as one of the warrior artists of Italy. Is this reflected in the painting we are contemplating—a battle? The landscape is desert, not a slice of green to be seen. Christ seems to be in a completely relaxed mode, an attitude of prayer, engrossed in conversation with his Father. Fasting has not emaciated him. He seems completely in control. The Temptation of Christ But, on the left is the Tempter. In Latin, “left” is Domenico Morelli (1823–1901) sinistra, from which we get our word “sinister”. It “The Temptation of Christ”, c. -

Cial Climber. Hunter, As the Professor Responsible for Wagner's Eventual Downfall, Was Believably Bland but Wasted. How Much

cial climber. Hunter, as the professor what proves to be a sordid suburbia, responsible for Wagner's eventual are Mitchell/Woodward, Hingle/Rush, downfall, was believably bland but and Randall/North. Hunter's wife is wasted. How much better this film attacked by Mitchell; Hunter himself might have been had Hunter and Wag- is cruelly beaten when he tries to ner exchanged roles! avenge her; villain Mitchell goes to 20. GUN FOR A COWARD. (Universal- his death under an auto; his wife Jo- International, 1957.) Directed by Ab- anne Woodward goes off in a taxi; and ner Biberman. Cast: Fred MacMurray, the remaining couples demonstrate Jeffrey Hunter, Janice Rule, Chill their new maturity by going to church. Wills, Dean Stockwell, Josephine Hut- A distasteful mess. chinson, Betty Lynn. In this Western, Hunter appeared When Hunter reported to Universal- as the overprotected second of three International for Appointment with a sons. "Coward" Hunter eventually Shadow (released in 1958), he worked proved to be anything but in a rousing but one day, as an alcoholic ex- climax. Not a great film, but a good reporter on the trail of a supposedly one. slain gangster. Having become ill 21. THE TRUE STORY OF JESSE with hepatitis, he was replaced by JAMES. (20th Century-Fox, 1957.) Di- George Nader. Subsequently, Hunter rected by Nicholas Ray. Cast: Robert told reporters that only the faithful Wagner, Jeffrey Hunter, Hope Lange, Agnes Moorehead, Alan Hale, Alan nursing by his wife, Dusty Bartlett, Baxter, John Carradine. whom he had married in July, 1957, This was not even good. -

Review Essay Faith and Film

RELIGION and the ARTS Religion and the Arts 13 (2009) 595–603 brill.nl/rart Review Essay Faith and Film David McNutt University of Cambridge Austin, Ron. In a New Light: Spirituality and the Media Arts. Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007. Pp. x + 95 + illus- trations. $12.00 paper. Humphries-Brooks, Stephenson. Cinematic Savior: Hollywood’s Making of the American Christ. London and Westport CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006. Pp. x + 160. $39.95 cloth. Malone, Peter, ed. Th rough a Catholic Lens: Religious Perspectives of Nine- teen Film Directors From Around the World. Communication, Culture, and Religion Series, eds. Paul J. Soukup, S.J. and Fran Plude. Lanham MD, Boulder CO, New York, and Plymouth, England: Sheed and Ward Books Division of Rowman and Littlefi eld Publishers, 2007. Pp. vi + 272. $25.95 paper. Walsh, Richard. Finding St. Paul in Film. New York and London: T. and T. Clark, 2005. Pp. vi + 218 + illustrations. $29.95 paper. * he dynamic relationship between religious faith and fi lm may be seen Tthrough a number of diff erent lenses. Th is essay will evaluate four examples of the growing number of recent books that address this connec- tion. Th e titles featured here include a volume about Hollywood’s portray- als of Jesus Christ on screen, an interpretation of fi lms in light of the fi gure and theology of Paul, a study of the infl uence of Catholicism upon the © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009 DOI: 10.1163/107992609X12524941450244 596 D. McNutt / Religion and the Arts 13 (2009) 595–603 work of directors from around the world, and a book investigating the pos- sibility of developing one’s spirituality through fi lmmaking. -

The Temptation of Christ

The Temptation of Christ REDEMPTION SERIES # 2 Ellen G. White 1877 Contents Confrontation in the Desert Adam and Eve and their Eden home The Test of Probation Paradise Lost. Plan of Redemption Sacrificial Offerings Appetite and Passion A Threat to Satan's Kingdom The Temptation Christ as a Second Adam Terrible Effects of Sin upon Man The First Temptation of Christ Significance of the Test Christ did no Miracle for Himself He Parleyed not with Temptation Victory through Christ The Second Temptation The Sin of Presumption Christ our Hope and Example The Third Temptation Christ's Temptation Ended Christian Temperance. Self-indulgence in Religion's Garb More Than One Fall. Health and Happiness. Strange Fire. Presumptuous Rashness and Intelligent Faith. Spiritism Character Development Confrontation in the Desert After the baptism of Jesus in Jordan He was led by the Spirit into the wilderness, to be tempted of the devil. When He had come up out of the water, He bowed upon Jordan's banks and pleaded with the great Eternal for strength to endure the conflict with the fallen foe. The opening of the heavens and the descent of the excellent glory attested His divine character. The voice from the Father declared the close relation of Christ to His Infinite Majesty: "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased." The mission of Christ was soon to begin. But He must first withdraw from the busy scenes of life to a desolate wilderness for the express purpose of bearing the threefold test of temptation in behalf of those He had come to redeem. -

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009 Annotations and citations (Law) -- Arizona. SHEPARD'S ARIZONA CITATIONS : EVERY STATE & FEDERAL CITATION. 5th ed. Colorado Springs, Colo. : LexisNexis, 2008. CORE. LOCATION = LAW CORE. KFA2459 .S53 2008 Online. LOCATION = LAW ONLINE ACCESS. Antitrust law -- European Union countries -- Congresses. EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW ANNUAL 2007 : A REFORMED APPROACH TO ARTICLE 82 EC / EDITED BY CLAUS-DIETER EHLERMANN AND MEL MARQUIS. Oxford : Hart, 2008. KJE6456 .E88 2007. LOCATION = LAW FOREIGN & INTERNAT. Consolidation and merger of corporations -- Law and legislation -- United States. ACQUISITIONS UNDER THE HART-SCOTT-RODINO ANTITRUST IMPROVEMENTS ACT / STEPHEN M. AXINN ... [ET AL.]. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y. : Law Journal Press, c2008- KF1655 .A74 2008. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Consumer credit -- Law and legislation -- United States -- Popular works. THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO CREDIT & BANKRUPTCY. 1st ed. New York : Random House Reference, c2006. KF1524.6 .A46 2006. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Construction industry -- Law and legislation -- Arizona. ARIZONA CONSTRUCTION LAW ANNOTATED : ARIZONA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND REGULATIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS AND COMMENTARY. [Eagan, Minn.] : Thomson/West, c2008- KFA2469 .A75. LOCATION = LAW RESERVE. 1 Court administration -- United States. THE USE OF COURTROOMS IN U.S. DISTRICT COURTS : A REPORT TO THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE ON COURT ADMINISTRATION & CASE MANAGEMENT. Washington, DC : Federal Judicial Center, [2008] JU 13.2:C 83/9. LOCATION = LAW GOV DOCS STACKS. Discrimination in employment -- Law and legislation -- United States. EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION : LAW AND PRACTICE / CHARLES A. SULLIVAN, LAUREN M. WALTER. 4th ed. Austin : Wolters Kluwer Law & Business ; Frederick, MD : Aspen Pub., c2009. KF3464 .S84 2009. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. -

On the Temptation of Jesus

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1993 On the temptation of Jesus. Thomas P. Sullivan University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Sullivan, Thomas P., "On the temptation of Jesus." (1993). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2212. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2212 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON THE TEMPTATION OF JESUS A Dissertation Presented by THOMAS P. SULLIVAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 1993 Department of Philosophy Copyright by Thomas P. Sullivan 1993 All Rights Reserved ON THE TEMPTATION OF JESUS A Dissertation Presented by THOMAS P. SULLIVAN Approved as to style and content by: Gareth B. Matthews, Chair Fred Feldman, Member To Fred, Lois, and Elizabeth In Memory of Lindsay ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank a number of people who have helped to see me through my graduate work in general and through this dissertation in particular. Before anyone else, I should mention my grandmothers, Elizabeth Stout and Laura Sullivan. Neither of them lived long enough to see me complete my Ph.D., but each of them always supported my academic career actively and enthusiastically. My parents, Ginny and Neal, have continued that support as long as I can remember, and they have consistently encouraged me to work hard (and to finish!). -

The Old Story Teller As a John the Baptist-Figure in Demille's Samson and Delilah

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 8 (2006) Issue 3 Article 2 The Old Story Teller as a John the Baptist-figure in DeMille's Samson and Delilah Anton Karl Kozlovic Flinders University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Kozlovic, Anton Karl. "The Old Story Teller as a John the Baptist-figure in DeMille's Samson and Delilah." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 8.3 (2006): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1314> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Norman Jewison: Commercial Success, Critical Failure

Norman Jewison: Commercial Success, Critical Failure An Honors Thesi s (1 D c199) by Ant.hnny L. Beeson Thes is Di reel.or Hall SUit.e Univprsit:,,- ('lune i e ,I nd i ana February, 1987 f'>...;pec\.pd dat(~ of graduation: >Ja;.- 19M! Sc '2.0 \! ·1 ' ... 1he.:;i:J L.D .. d\J·f2;'( I ;;';;"1 I QS7 , BJ.f4 Table of Contents In t roduc~ T i. on .. Commen t a 1':'>- on: F. i . ;:-; . r ..... 6 .And Jusr.icp for Ai ] 0 1:2 T h p f 0 \J r f, Lm s j n rom par j s r' n . l ;) Jewison as a riirertor. 1 I Cone 1 us jon .•.• 1 H R i. hI i og raph:v •. I~ Introduction The f ~ I m s () f '\ 0 r man J tCO~'; i son are a stu d :.~ 1 n C Cl n t nl s t s . h 11 i ] e r-tlmost Cill of t.he fi Ims in Ci (1irr>ctin!:!, car'eer hhi('h t)(~gan In 1::lt:i2 hCi n=~ been successful, thpy ha\e alsn bf~en (-h('> c.;llh.)(·et ni neg;-lt \\-P, !'-.()met JOlt'S revIews from film C I' j t. I rs . for I-',pst J) reet.or, In the Heat Flddler' un tl:e h'o(~f, oid not go unsC'athpd. ( Fin I p r, 2 (i ( - 2 () 8 i (,\1 0 cit z, 1 H b - j 9 j ) fn the se(' t -j ons on :.. 0 r m Ci 'I ,J e his () n in the I ~1 i-~; e d i T. -

Moments of Doubt and Pain: the Symbol of Jesus Christ in the Last

MOMENTS OF DOUBT AND PAIN: THE SYMBOL OF JESUS CHRIST IN THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST AND APOCALYPSE NOW by MARIA ELIZABETH KLECKLEY (Under the Direction of Carolyn Jones Medine) ABSTRACT This thesis explores the intersection of the fields of film studies and religion. That intersection, after being studied through several works on the topic, is further explored through the films The Last Temptation of Christ and Apocalypse Now. Each of these films is analyzed for their religious aspects, more specifically through their depictions of a Christ figure. INDEX WORDS: Film Studies, Film Theory, The Last Temptation of Christ, Apocalypse Now, Jesus Christ, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola MOMENTS OF DOUBT AND PAIN: THE SYMBOL OF JESUS CHRIST IN THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST AND APOCALYPSE NOW by MARIA ELIZABETH KLECKLEY BA, University of South Carolina, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 © 2014 Maria Elizabeth Kleckley All Rights Reserved MOMENTS OF DOUBT AND PAIN: THE SYMBOL OF JESUS CHRIST IN THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST AND APOCALYPSE NOW by MARIA ELIZABETH KLECKLEY Major Professor: Carolyn Jones Medine Committee: Sandy D. Martin Christopher Sieving Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2014 iv DEDICATION To W.W. My star, my perfect silence Psalm 16:6 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It’s entirely obnoxious to begin to think of all the people who deserve acknowledgement for encouraging and guiding me over the last two years, but it’s a fantastic means of procrastination, so here we go. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

Actor Jeffrey Hunter Dies of Injuries; Fall Believed Cause

Actor Jeffrey Hunter Dies of Injuries; Fall Believed Cause Actor Jeffrey Hunter, who portrayed Christ in the remake of the motion picture classic "King of Kings," died Tuesday from injuries believed suffered in a fall at his Van Nuys home, police reported. The 42-year-old Hunter, whose true name was Henry H. McKinnies Jr., was found unconscious by an unidentified friend Monday at 4:45 p.m. at the actor's home, 13451 Erwin St. Hunter had apparently fallen down a flight of stairs. The friend called the Fire Department and an ambulance. Taken to Valley Receiving Hospital, Hunter underwent surgery Monday night and died Tuesday at 9:30 a.m. An autopsy revealed he died of head injuries. Detective Sgt. Jesse A. Tubbs began an investigation of the apparent accident. He was unable to talk immediately to Hunter's third wife, Emily, who was reported under sedation. The actor formerly was married to actresses Barbara Rush, by whom he had a son, and Joan (Dusty) Bartlett, by whom he had two sons. One of Hunter's other important screen roles was that of the nephew of Mayor Skeffington, played by Spencer Tracy, in "The Last Hurrah." His other films included "Call Me Mister," "The Frogmen," "Red Skies of Montana," "Sailor of the King," "Seven Angry Men," "Proud Ones," "Kiss Before Dying," "Hell to "Eternity," "Sergeant Rutledge" and "Brainstorm." During the early 1960s he starred in "Temple Houston, a television series about a frontier lawyer. Hunter was a native of New Orleans, a graduate of Northwestern University and a Navy veteran of World War II.