Reitz Or Wrong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Test and Registration Dates & Testing Locations 2013/2014

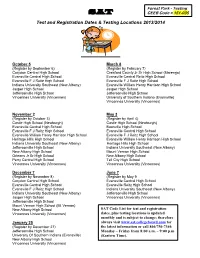

Forest Park - Testing SAT CEEB Code = 151-035 Test and Registration Dates & Testing Locations 2013/2014 October 5 March 8 (Register by September 6) (Register by February 7) Corydon Central High School Crawford County Jr Sr High School (Marengo) Evansville Central High School Evansville Central Reitz High School Evansville F J Reitz High School Evansville F J Reitz High School Indiana University Southeast (New Albany) Evansville William Henry Harrison High School Jasper High School Jasper High School Jeffersonville High School Jeffersonville High School Vincennes University (Vincennes) University of Southern Indiana (Evansville) Vincennes University (Vincennes) November 2 May 3 (Register by October 3) (Register by April 4) Castle High School (Newburgh) Castle High School (Newburgh) Evansville Central High School Boonville High School Evansville F J Reitz High School Evansville Central High School Evansville William Henry Harrison High School Evansville F J Reitz High School Heritage Hills High School Evansville William Henry Harrison High School Indiana University Southeast (New Albany) Heritage Hills High School Jeffersonville High School Indiana University Southeast (New Albany) New Albany High School Mount Vernon High School Orleans Jr Sr High School New Albany High School Perry Central High School Tell City High School Vincennes University (Vincennes) Vincennes University (Vincennes) December 7 June 7 (Register by November 8) (Register by May 9 Corydon Central High School Evansville Central High School Evansville Central High School -

Newsletter Dated October 1, 2013

Neighborhood Associations working together to preserve, enhance, and promote U N O E the Evansville neighborhoods NEIGHBOR TO NEIGHBOR A Publication of United Neighborhoods of Evansville Volume 13 Issue 10 20 N.W. Fourth Street, Suite 501, 47708 October 2013 Website: www.unoevansville.org Email: [email protected] Phone 812-428-4243 From the President …… UPCOMING UNOE DATES IT IS NOT TOO EARLY TO THINK Oct. 15th - Sparkplug Comm. ABOUT CHRISTMAS GIFTS Meeting Oct. 16th- Board Meeting This year, why not think about giving family holiday gifts that Oct. 24th - SPARKPLUG are lasting and introduce them to attractions in Evansville. BANQUET They can probably be ordered via the internet or telephone. Here are some suggestions that offer gift certificates: Please remember there Mesker Park Zoo and Botanic Garden - The zoo has over 700 animal species will be no and the botanic garden has a variety of large trees and ever changing seasonal plants. UNOE General Meetings 1545 Mesker Park Dr. in November & December 812-435-6143 MeskerParkZoo.com due to the holidays. Evansville Museum of Arts, History and Science (Submersive Planetarium Our October meeting will opens in Spring of 2014) 411 S.E. Riverside Dr. be the Sparkplug Banquet 812-425-2406 emuseum.org on Thursday, October 24th. Evansville African American Museum - Shows the roots of the African American residents in the 20th century. Our next 579 S Garvin St. General Meeting 812-423-5188 EvansvilleAAMuseum.wordpress.com will be Thursday, cMoe Koch Family Children's Museum of Evansville - Speak Loud! Live January 23rd, 2014 Big! Work Smart ! Quack Galleries! 22 SE Fifth St. -

City of Evansville, Indiana Downtown Master Plan

City of Evansville, Indiana Downtown Master Plan FINAL REPORT October 2001 Claire Bennett & Associates KINZELMAN KLINE GOSSMAN 3 Table of Contents Table of Contents F. Market Positioning 3. Conclusions and Recommendations Acknowledgments IV. Metropolitan Area Commercial Centers 1. Introduction 1.1 Planning Objectives 4. Strategic Redevelopement I. Target Area Map 4.1 Town Meeting and S.W.O.T. II. Zoning Map 4.2 Design Charrette Process 2. Strategic Planning 4.3 Strategic Vision 2.1 Strategic Thinking (issues, goals, and objectives) 5. Conclusions and Recommendations 1. Develop Three Distinctive Downtown Districts 2.2 Urban Design Principles 5.1 The Vision 2. Reintroduce Evansville to Downtown Living 3. Initial Assessment 5.2 Downtown Evansville’s Revitalization 4.4 Redevelopment Opportunities 3.1 History, Diversity & Opportunity 1. Target Market 3.2 Physical Assessment of Downtown I. Overall Concept Plan Retail, Housing, Office II. District Diagram 1. Transportation, Circulation, and Parking 2. Principles of Revitalization III. Main Street Gateway Concept I. Parking Inventory Map 3. Organizational Strategy IV. Main Street Phasing Plan II. Estimated Walking Coverage Map V. Main Street Corridor Phasing Plan 4. Commercial Strategy 3.3. Market Analysis VI. Main Street “Placemaking” 5.3 Implementation 1. Introduction VII. Streetscape Enhancements 1. Strategic Goals A. Background and Project Understanding VIII. Pilot Block 2. Development and Business Incentives IX. Civic Center Concept Plan 2. Fact Finding and Analysis 3. Policy Making and Guidance X. Fourth Street Gateway Concept A. Project Understanding XI. Riverfront West Concept 4. Sustainable Design B. Market Situation XII. Gateway and Wayfinding 5. Final Thoughts C. Trade Area Delineations XIII. -

Mccutchan Family

Descendants of William McCutchan Generation No. 1 1. WILLIAM1 MCCUTCHAN was born 01 August 1775 in County Westmeathe, Ireland, and died 22 October 1836. He married MARY ANN VICKERSTAFF. She was born 16 September 1777 in County Meath, Ireland, and died 22 September 1858. More About WILLIAM MCCUTCHAN: Burial: Hillard's Cemitary (Blue Grass) Indiana More About MARY ANN VICKERSTAFF: Burial: Hillard's Cemitary (Blue Grass) Indiana Children of WILLIAM MCCUTCHAN and MARY VICKERSTAFF are: 2. i. SAMUAL2 MCCUTCHAN, b. 16 October 1797, County Longford, Ireland; d. 26 November 1880. 3. ii. ALEXANDER DENNISON MCCUTCHAN, b. 1800; d. 1843. 4. iii. WILLIAM JR. MCCUTCHAN, b. 1801; d. 1843. 5. iv. JOHN MCCUTCHAN, b. 16 July 1800, Co. Longford, Ireland; d. 1840. 6. v. THOMAS MCCUTCHAN, b. 05 April 1803, Co. Longford Ireland; d. 04 January 1886. 7. vi. SARAH BOND, b. 20 March 1807; d. 10 June 1889. 8. vii. GEORGE BOND MCCUTCHAN, b. 03 February 1812; d. 02 January 1884. 9. viii. ROBERT MCCUTCHAN, b. February 1817, Sullivan Co. NY; d. March 1863. 10. ix. JAMES A. MCCUTCHAN, b. 05 April 1818; d. 29 July 1885. Generation No. 2 2. SAMUAL2 MCCUTCHAN (WILLIAM1) was born 16 October 1797 in County Longford, Ireland, and died 26 November 1880. He married AGNES (NANCY) MCCRABBIE 23 April 1820 in Bethyl, N.Y., Sullivan Co., daughter of ROBERT MCCRABBIE. She was born 29 May 1805 in Leith, Scotland, and died 19 September 1880. Notes for SAMUAL MCCUTCHAN: First Postmaster of McCutchanville, IN More About SAMUAL MCCUTCHAN: Burial: McCutchanville Church Cemetery More About AGNES (NANCY) MCCRABBIE: Burial: McCutchanville Church Cemetery More About SAMUAL MCCUTCHAN and AGNES MCCRABBIE: Marriage: 23 April 1820, Bethyl, N.Y., Sullivan Co. -

Evansville: the Economic History and Development of a River Town in the 1800'S

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 188 SO 019 321 AUTHOR Adams, Ruth; And Others TITLE Evansville: The Economic History and Development of a River Town in the 1800's. Grade 7. IN.-TU(1110N Evansville-Vanderburgh School Corp., Ind. SPONS AGENCY Indiana State Dept. of Education, Indianapolis. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 78p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Economics Education; Grade 7; Junior High Schools; Learning Modules; Local History; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Indiana (Evansville); Ohio River ABSTRACT This teacher's guide for the instruction of economic concepts at the seventh grade level uses Evansville's (Indiana) historical development to further the study of concepts such as economic needs and wants, factors of production, and opportunity cost. The first part of the guide, "Introducing Basic Economic Concepts," uses the text "Enterprise Island: A Simple Economy" and the student activity booklet "A Study of Basic Economics." The correspondinc chapters from the activity booklet are reproduced for each unit. The second part of the guide focuses on Evansville, and thz reading materials and student activity sheets are reproduced as student handouts. An 18-item test on economic terms and a 49-item examination on Evansville are included. (DJC) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ***********************************K*********************************** Evansville:The CO co Economic History and Ci Development of a River Town in the 1800's. LL.1 U S DEPARTMENT CW EDUCATION OtIrce of Education/1i Research and Improvement iEDUCATIONAL RFSOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organizabon originating it C Minor changes have been made tr, improve reproduction Quattty POmts Of wew Or Op. -

Accounting, Auditing & Bookkeeping Adjustment

2016 Southwest Indiana Chamber Membership Directory ad.pdf 1 6/22/2016 5:37:45 PM Umbach & Associates, LLP Kitch & Schreiber, Inc. _________________ IGT Indiana 400 Bentee Wes Ct., Evansville, IN 47715-4060 402 Court St., Evansville, IN 47708 1302 N. Meridian St., Indianapolis, IN 46202 (812) 428-224 • www.umbach.com (812) 424-7710 • www.kitchandschreiber.com (317) 264-4637 • web.1si.org/Retail/IGT-Indiana-2694 ______________________ ______________________ AGRICULTURE ______________________ C Vowells & Schaaf, LLP Lumaworx Media PRODUCTION/CROPS Indoor Golf League P.O. Box 119, Evansville, IN 47701 _________________ P.O. Box 608, Mt. Vernon, IN 47620 M 101 N.W. First St., Evansville, IN 47708 (812) 421-4165 • www.vscpas.com (812) 480-9057 812-459-1355 • www.lumaworxmedia.com Azteca Milling, LP ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ Y 15700 Hwy. 41 North, Evansville, IN 47725 Weinzapfel & Co., LLC Media Mix Communications, Inc. Painting With a Twist Evansville (972) 232-5300 • www.aztecamilling.com 5625 E. Virginia St., Ste. A, Evansville, IN 47715 CM 21 S.E. Third Steet, Suite 500 1301 Mortensen Lane, Evansville, IN 47715 4630 Bayard Park Dr., Evansville, IN 47716 ______________________ Evansville, IN 47708 (812) 474-1015 • www.weinzapfel.com (812) 473-0600 • www.mediamix1.com CGB Diversified Services (812) 304-0243 MY _________________ ______________________ www.paintingwithatwist.com/evansville (812) 464-9161 (800) 880-7800 1811 N. Main St., Mt. Vernon, IN 47620 ______________________ MOB Media (812) 833-3074 • www.cgb.com CY www.hsccpa.com ______________________ Sky Zone Indoor Trampoline Park ADJUSTMENT & 800 E. Oregon St., Evansville, IN 47711 49 N. Green River Rd., Evansville, IN 47715 CMY (812) 773-3526 Consolidated Grain & Barge ______________________ (812) 730-4759 • www.skyzone.com/evansville Real Solutions. -

Download The

Group Tour HERITAGE &History 2016-17 Planning Guide Colonial America The American Civil War Melting Pot Native Peoples The Great Expansion The American West Come experience the story that’s touched so many. Billy Graham preaching in Times Square, New York, 1957 Visit the Billy Graham Library in Charlotte and discover how God called a humble farmer’s son to preach the Good News of His love to 215 million people face to face. Retrace his dynamic journey as history comes to life through inspiring multimedia presentations and state-of-the-art exhibits. FREE ADMISSION Monday to Saturday, 9:30–5:00 • BillyGrahamLibrary.org • 704-401-3200 Reservations are required for groups of 10 or more; email [email protected] or call 704-401-3270. 4330 Westmont Drive • Charlotte, North Carolina A ministry of Billy Graham Evangelistic Association ©2015 BGEA 2 Heritage & History • GroupTour.com 2016-17 Planning Guide 3 Join Our City of Dreamers, Idealists, Rebels, and Loyalists Around here, history is living, breathing, and sometimes even galloping past you. With fun and interactive activities throughout more than 300 acres, we’ll keep your group busy thinking and dreaming. Visits can include on-site lodging, dining, 18th-century tavern meals, and entertainment. Inspire your group with a lively Colonial Williamsburg experience in beautiful Virginia. Special savings available for groups of 15 or more. To book your group call 1-800-228-8878 or email [email protected] colonialwilliamsburg.com/grouptours 2 Heritage & History • GroupTour.com Reader Service Card #217 2016-17 Planning Guide 3 © 2016 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation 3/16-TIS-11384875 2465 112th Avenue Holland, MI 49424-9657 1-800-767-3489 616-393-2077 fax: 616-393-0085 grouptour.com Just the stats, Publisher ma’am Elly DeVries I President 12 Editorial There are more than 80,000 properties listed on the Mary Lu Laffey I Editor FROM THE David Hoekman I Managing Editor EDITOR National Register of Historic Places. -

Evansville Historic Preservation Month

the Church on Oak Street. This Gothic Revival EVANSVILLE HISTORIC WALKING TOURS PRESERVATION MONTH building serves the oldest African American AND LECTURES congregation in the city, organized in 1865. Liberty Evansville’s Department of Metropolitan Baptist erected a sanctuary in 1882 that was ruined Development (DMD), Reitz Home Museum, and Presentation: WWI Evansville Nurses in 1887. The present sanctuary rose from the rubble Old Courthouse Foundation of Vanderburgh Thursday, May 3, 7:00p.m.-8:00p.m. by County 7 months later. This site was a meeting place for the County present a full slate of lectures, tours, Archivist Amber Gowen at the Reitz Home Museum African-American neighborhood of Baptisttown activities, and events on the Vanderburgh County Carriage House. 112 women tended the area’s and organizing center for African-Americans for Bicentennial and the World War I Centennial. medical needs as graduate nurses in local hospitals, their 115 year struggle for Civil Rights in and many lived in local Graduate Nurses Evansville. Guide: Clarence Tobin. FEATURED SPEAKERS Association homes. When the Army called for nurses, these homes became centers of recruitment. The Missing Buildings of Main Street Tour Preservation Keynote Address By war’s end, 56 Vanderburgh County nurses Thursday, May 17, 5:00p.m.-6:30p.m. Gather at Indiana Landmarks in Evansville and Beyond experienced the horrors of war as intimately as any Main and 2nd Street. From the Hopkins Dry Goods Marsh Davis male veteran but without their stories being told. Building to The American Theater, Main Street Thursday, May 17, 7:00p.m. Reitz Home Join us to hear some stories from these veterans. -

Deaconess Aquatic Center Regional Cities 2.0 Update

MEMBER BUSINESS DIRECTORY - PAGE 36 #keepitlocal Regional Cities 2.0 Update Deaconess Aquatic Center NEW INDOOR SWIMMING FACILITY greater evansville I-69 HOMEBUYING BRIDGING OUR DESTINATION FOR MILLENNIALS COMMUNITIESgreater evansville #1 EVANSVILLE INDIANA greater evansville LOCAL EATS, DRINKS, COUPONS & MORE! Pictured: Baret Family Selfie, Self.e Alley, Downtown Evansville. Photo: Alex Morgan Imaging CountryMark Top Tier Gasoline BecauseCountryMark they are worth it. Top Tier Gasoline Because they are worth it. Letter from President & CEO The great Michelangelo once said, “The problem human beings face is not that we aim too high and fail, but that we aim too low and succeed.” Fortunately, the leaders and officials of Southwest Indiana have aimed high in the goals for bettering our community, and in doing so are well on the way to succeeding. This year’s edition of Keep It Local showcases the many ways that our region continues growing through infrastructure upgrades, quality-of-life improvements and an increasing number of entertainment options. By aiming high, local elected officials and business leaders were able to secure millions in funds through the Regional Cities Initiative, and four years in, many projects meant to attract and retain talent to our region are coming to fruition, if not well on their way. Success, indeed. In the pages ahead, we take a look at several projects that are cementing Evansville as a top attraction in the Midwest: the continued progress of The Post House, a unique mixed-use development that will feature smart-technology labs, retail businesses, apartment living and an open outdoor community space; the upcoming groundbreaking for the Deaconess Aquatic Center, which will be the largest indoor swimming facility in the region; an update on the I-69 bridge that will connect Indiana and Kentucky and is expected to bring a huge economic impact; and several new restaurants and bars with a wide diversity of food and drink options, led by Mo’s House and Myriad Brewery. -

Fall 2017 (PDF)

DEPARTMENT Fall 2017 Vol. 1 MUSIC MAGAZINEof From the Chair It’s no exaggeration for me to say that it has been an exciting year for the Department of Music. Performances by musical and cultural icons, teaching and student awards, and events that engage with our com- munity are just a few of the oppor- tunities that our students experienced in the course of this academic year. Among the many accomplishments and activities you will discover in the following pages, I’m pleased to share news that the Depart- ment of Music received word of its re-accreditation with the National Association of Schools of Music in July. UE is among only 20 percent of institutions accepted by NASM’s highly selective accreditation process. Our membership represents an endorse- ment of the quality of programs and degrees available in our department. Our accreditation is the culmination of a multi-year process and the work of numerous members of our faculty and staff. Many thanks for their efforts! One outgrowth of our accreditation process has been departmental strategic planning, about which you can find more details on the following page. Needless to say, the engagement of our friends, students, alumni, faculty, and administrators in this process has been both an energizing experience, and a source of great ideas that will guide many of our efforts in the coming years. Wylie Wins Teaching Award Another result has been the decision to make the historic Victory Mary Ellen Wylie, professor of music therapy, was named Theatre the home for many of our large ensemble concerts. -

College Achievement Program: Giving High School Students a Jump Start to Higher Education

Spring 2013 College Achievement Program: Giving high school students a jump start to higher education on-track to finish in four years. I was able to study abroad and get involved with extra-curricular activities,” said Christy Hamon, a CAP graduate from Harrison High School in Evansville, who attends USI and will graduate this spring. CAP is not only drawing students toward college, it’s drawing them to USI. “As far as a recruitment tool, it’s doing its job,” Dumond says. More than half of CAP students end up studying at USI. “CAP really serves as a front door for the intellectual capital the University offers to prospective students,” said Taylor Gogel, a former Heritage Hills High School CAP student and current USI student. Continued on page 4 “ I’m thankful my children had the opportunity to earn college credits through CAP. The rigor prepared them for college and kept them focused USI’s College Achievement Program (CAP), a cooperative program between the University and high schools throughout the state, and engaged in their last semesters of high gives motivated high school juniors and seniors an opportunity to school. It also turned out to be a fabulous financial take entry-level college courses from approved high school faculty during the school day. The program also gives students time for decision. My twin daughters are graduating extracurricular activities, study abroad opportunities, and increases from USI in four years, even though one transferred chances of on-time graduation. from another institution and the other changed “Students are more likely to complete a certificate or a degree, her major and studied abroad. -

The Art Collection at Sunset Funeral Home & Memorial

Fishing Under the Ohio Street Bridge Signed, limited edition canvas Giclée by Cedric Hustace the art collection at Sunset funeral home & memorial park Sunset Memorial Park has been a proud member of the Evansville community since 1948. The 2008 addition of Sunset Funeral Home, the only funeral home in the Tri-State area located in a cemetery, means unprecedented convenience and savings for the families we serve. Located at the highest point in Evansville, Sunset Funeral Home is truly an inspirational setting with breathtaking views over- looking the surrounding countryside. When it came time to select the artwork, we wanted our walls to tell a story to capture the flavor of the Evansville area and we embarked on a journey to find artwork depicting the area’s history. On that journey, we discovered that the city is filled with talented local artists. In fact, Evansville is listed #2 in an article titled “10 Great Towns for Working Artists” in the February 2008 issue of Art Calendar, a national trade magazine for visual artists. Making the final selections was extremely difficult as we found so many categories and artists we liked. Sunset Funeral Home is delight- ed to present to you our choices reflecting the area’s rich history and heritage for our permanent collection. We hope you like what we’ve chosen as you walk through the funeral home. Each piece includes a vignette describing the art and informa- tion on the artist. This program, which provides the same informa- tion, is yours to keep. If only the walls could talk—we think ours do and they tell a wonderful story of the talented artists in our area and their view of our little piece of this world.