Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 8-18, 2021

July 8-18, 2021 Val Underwood Artistic Director ExecutiveFrom Directorthe Dear Friends: to offer a world-class training and performance program, to improve Throughout education, and to elevate the spirit of history, global all who participate. pandemics have shaped society, We are delighted to begin our season culture, and with Stars of Tomorrow, featuring institutions. As many successful young alumni of our we find ourselves Young Singer Program—including exiting the Becca Barrett, Stacee Firestone, and COVID-19 crisis, one pandemic and many others. Under the direction subsequent recovery that comes to of both Beth Dunnington and Val mind is the bubonic plague—or Black Underwood, this performance will Death—which devastated Europe and celebrate the art of storytelling in its Asia in the 14th century. There was a most simple and elegant state. The silver lining, however, as it’s believed season also includes performances that the socio-economic impacts of by many of our very own, long- the Plague on European society— time Festival favorites, and two of particularly in Italy—helped create Broadway’s finest, including HPAF the conditions necessary for what is Alumna and 1st Place Winner of arguably the greatest post-pandemic the 2020 HPAF Musical Theatre recovery of all time—the Renaissance. Competition, Nyla Watson (Wicked, The Color Purple). Though our 2021 Summer Festival is not what was initially envisioned, As we enter the recovery phase and we are thrilled to return to in-person many of us eagerly await a return to programming for the first time in 24 “normal,” let’s remember one thing: we months. -

Gareth Owen Theatrical Sound Designer

Gareth Owen Theatrical Sound Designer Musical Theatre Sound Design Awards highlights include : Outer Critics Circle Award COME FROM AWAY Schoenfeld, New York Olivier Award MEMPHIS Shaftesbury Theatre, London Craig Noel Award COME FROM AWAY La Jolla Playhouse, San Diego Pro Sound Award MEMPHIS Shaftesbury Theatre, London Olivier Award MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG Comedy Theatre, London Olivier Nomination TOP HAT Aldwych Theatre, London Tony Nomination END OF THE RAINBOW Belasco Theatre, New York Olivier Nomination END OF THE RAINBOW Trafalgar Studios, London Tony Nomination A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC Walter Kerr, New York Upcoming Sound Design highlights include : Susan Stroman’s YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN on London’s West End; Stephen Schwartz’s PRINCE OF EGYPT (World Premiere), and Des McAnuff’s DONNA SUMMER PROJECT both on Broadway; COME FROM AWAY in Toronto and on tour in the USA; Don Black’s THE THIRD MAN (World Premiere) in Vienna; BODYGUARD in Madrid; and the JERSEY BOYS International Tour. International Musical Sound Design highlights include : Lead Producer Director A BRONX TALE (World Première) Long Acre, Broadway Dodgers Theatrical Robert DeNiro COME FROM AWAY (World Première) Schoenfeld, Broadway Junkyard Dog Chris Ashley STRICTLY BALLROOM (European Première) Worldwide (2 versions) Global Creatures Drew McConie DISNEY’S HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME Worldwide (5 versions) Disney Scott Schwartz SCHIKANEDER (World Premiere) Raimund, Vienna Stephen Schwartz & VBM Trevor Nunn CINDERELLA Rossia, Moscow Stage Entertainment Lindsay Posner SECRET GARDEN Lincoln -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Kathy Kahn

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press contact: Kathy Kahn, [email protected], 510-418-8523 Theater contact: Harriet Schlader, [email protected], 510-531-9597 Woodminster Summer Musicals AUGUST 2015 -- CALENDAR INFORMATION WHAT: The Producers PERFORMED BY: Woodminster Summer Musicals by Producers Associates, Inc. WHERE: Woodminster Amphitheater in Joaquin Miller Park, 3300 Joaquin Miller Road, Oakland WHEN: August 7-16, 2015 PERFORMANCES: August 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16 - 8 p.m. TICKETS: 510-531-9597, or www.woodminster.com, $28-$59 (Discounts for children, seniors, groups) PREVIEW PERFORMANCE: August 6, 8 p.m., All tickets $18 at the door. (Since it's a rehearsal, the show may be stopped to solve technical problems.) A New Mel Brooks Musical, Book by Mel Brooks and Thomas Meehan, Music and Lyrics by Mel Brooks, Based on the 1968 Film, Original direction and choreography by Susan Stroman, Produced by arrangement with Music Theatre International. Photo caption: Greg Carlson* as Max Bialystock, Melissa Reinerston as Ulla, and John Tichenor* as Leo Bloom. PRESS RELEASE The Producers Opens August 7 at Woodminster Summer Musicals Stage Musical is Adapted from Mel Brooks' Classic Comedy Film July 20, 2015, Oakland, CA -- Producers Associates, Inc. announces that the 2015 season of Woodminster Summer Musicals will continue with The Producers, the hit Broadway musical based on the 1968 Mel Brooks film of the same name. It will run August 7-16 at Woodminster Amphitheater in Oakland's Joaquin Miller Park, located at 3300 Joaquin Miller Road in the Oakland hills. The Producers tells the story of a down-on-his-luck Broadway producer and his nervous accountant, who together come up with a scheme to make a million dollars (each) by producing the worst flop in Broadway history. -

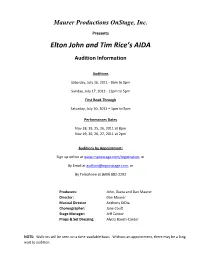

Elton John and Tim Rice's AIDA

Maurer Productions OnStage, Inc. Presents Elton John and Tim Rice’s AIDA Audition Information Auditions Saturday, July 16, 2011 - 9am to 5pm Sunday, July 17, 2011 - 12pm to 5pm First Read-Through Saturday, July 30, 2011 – 1pm to 5pm Performances Dates Nov 18, 19, 25, 26, 2011 at 8pm Nov 19, 20, 26, 27, 2011 at 2pm Auditions by Appointment: Sign up online at www.mponstage.com/registration, or By Email at [email protected], or By Telephone at (609) 882-2292 Producers: John, Diana and Dan Maurer Director: Dan Maurer Musical Director Anthony DiDia Choreographer: Jane Coult Stage Manager: Jeff Cantor Props & Set Dressing: Alycia Bauch-Cantor NOTE: Walk-ins will be seen on a time-available basis. Without an appointment, there may be a long wait to audition. Auditions for Elton John & Tim Rice’s AIDA Index 1. About the Show 2. Available Roles 3. What You Need to Know About the Audition 4. Audition Application 5. Calendar for Conflicts 6. Musical Numbers 7. Audition Monologues 1 Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida Directed by Dan Maurer Part Broadway musical, part dance spectacular and part rock concert, AIDA is an epic tale about the power and timelessness of love. The show features over twenty roles for singers, dancers, and actors of various races and will be staged by the award winning production team that brought shows like Man of La Mancha and Singin’ in the Rain to Kelsey Theatre. Winner of four Tony Awards when Disney’s Hyperion Theatrical Group first brought it to Broadway, AIDA features music by pop legend Elton John and lyrics by Tim Rice, who wrote the lyrics for hit shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita. -

Musical! Theatre!

Premier Sponsors: Sound Designer Video Producer Costume Coordinator Lance Perl Chrissy Guest Megan Rutherford Production Stage Manager Assistant Stage Manager Stage Management Apprentice Mackenzie Trowbridge* Kat Taylor Lyndsey Connolly Production Manager Dramaturg Assistant Director Adam Zonder Hollyann Bucci Jacob Ettkin Musical Director Daniel M. Lincoln Directors Gerry McIntyre+ & Michael Barakiva+ We wish to express our gratitude to the Performers’ Unions: ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS AMERICAN GUILD OF VARIETY ARTISTS SAG-AFTRA through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the Artists to appear on this program. * Member of the Actor's Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. + ALEXA CEPEDA is delighted to be back at The KRIS COLEMAN* is thrilled to return to the Hangar. Hangar! Select credits: Mamma Mia (CFRT), A Broadway Credit: Jersey Boys (Barry Belson) Chorus Line (RTP), In The Heights (The Hangar Regional Credit: Passing Strange (Narrator), Jersey Theatre), The Fantasticks (Skinner Boys - Las Vegas (Barry Belson), Chicago (Hangar Barn), Cabaret (The Long Center), Anna in the Theatre, Billy Flynn), Dreamgirls (Jimmy Early), Sister Tropics (Richard M Clark Theatre). She is the Act (TJ), Once on This Island (Agwe), A Midsummer founder & host of Broadway Treats, an annual Nights Dream (Oberon) and Big River (Jim). benefit concert organized to raise funds for Television and film credits include: The Big House Animal Lighthouse Rescue (coming up! 9/20/20), and is (ABC), Dumbbomb Affair, and The Clone. "As we find ourselves currently working on her two-person musical Room 123. working through a global pandemic and race for equality, work Proud Ithaca College BFA alum! "Gracias a mamacita y papi." like this shows the value and appreciation for all. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

Student Guide Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS STUDENT GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS APRIL 13 - JUNE 21, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writers.....................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team........................................................................................................................................................................8 Presents for Mrs. Rogers......................................................................................................................................................................9 Will Rogers..............................................................................................................................................................................................11 Wiley Post, Aviation Marvel..............................................................................................................................................................16 -

Cast Biographies Chris Mann

CAST BIOGRAPHIES CHRIS MANN (The Phantom) rose to fame as Christina Aguilera’s finalist on NBC’s The Voice. Since then, his debut album, Roads, hit #1 on Billboard's Heatseekers Chart and he starred in his own PBS television special: A Mann For All Seasons. Chris has performed with the National Symphony for President Obama, at Christmas in Rockefeller Center and headlined his own symphony tour across the country. From Wichita, KS, Mann holds a Vocal Performance degree from Vanderbilt University and is honored to join this cast in his dream role. Love to the fam, friends and Laura. TV: Ellen, Today, Conan, Jay Leno, Glee. ChrisMannMusic.com. Twitter: @iamchrismann Facebook.com/ChrisMannMusic KATIE TRAVIS (Christine Daaé) is honored to be a member of this company in a role she has always dreamed of playing. Previous theater credits: The Most Happy Fella (Rosabella), Titanic (Kate McGowan), The Mikado (Yum- Yum), Jekyll and Hyde (Emma Carew), Wonderful Town (Eileen Sherwood). She recently performed the role of Cosette in Les Misérables at the St. Louis MUNY alongside Norm Lewis and Hugh Panero. Katie is a recent winner of the Lys Symonette award for her performance at the 2014 Lotte Lenya Competition. Thanks to her family, friends, The Mine and Tara Rubin Casting. katietravis.com STORM LINEBERGER (Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny) is honored to be joining this new spectacular production of The Phantom of the Opera. His favorite credits include: Lyric Theatre of Oklahoma: Disney’s The Little Mermaid (Prince Eric), Les Misérables (Feuilly). New London Barn Playhouse: Les Misérables (Enjolras), Singin’ in the Rain (Roscoe Dexter), The Music Man (Jacey Squires, Quartet), The Student Prince (Karl Franz u/s). -

Guest Artists

Guest Artists George Hamilton, Broadway and Film Actor, Broadway Actresses Charlotte D’Amboise & Jasmine Guy speaks at a Chicago Day on Broadway speak at a Chicago Day on Broadway Fashion Designer, Tommy Hilfiger, speaks at a Career Day on Broadway SAMPLE BROADWAY GUEST ARTISTS CHRISTOPHER JACKSON - HAMILTON Christopher Jackson- Hamilton – original Off Broadway and Broadway Company, Tony Award nomination; In the Heights - original Co. B'way: Orig. Co. and Simba in Disney's The Lion King. Regional: Comfortable Shoes, Beggar's Holiday. TV credits: "White Collar," "Nurse Jackie," "Gossip Girl," "Fringe," "Oz." Co-music director for the hit PBS Show "The Electric Company" ('08-'09.) Has written songs for will.i.am, Sean Kingston, LL Cool J, Mario and many others. Currently writing and composing for "Sesame Street." Solo album - In The Name of LOVE. SHELBY FINNIE – THE PROM Broadway debut! “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert” (NBC), Radio City Christmas Spectacular (Rockette), The Prom (Alliance Theatre), Sarasota Ballet. Endless thanks to Casey, Casey, John, Meg, Mary-Mitchell, Bethany, LDC and Mom! NICKY VENDITTI – WICKED Dance Captain, Swing, Chistery U/S. After years of practice as a child melting like the Wicked Witch, Nicky is thrilled to be making his Broadway debut in Wicked. Off-Broadway: Trip of Love (Asst. Choreographer). Tours: Wicked, A Chorus Line (Paul), Contact, Swing! Love to my beautiful family and friends. BRITTANY NICHOLAS – MEAN GIRLS Brittany Nicholas is thrilled to be part of Mean Girls. Broadway: Billy Elliot (Swing). International: Billy Elliot Toronto (Swing/ Dance Captain). Tours: Billy Elliot First National (Original Cast), Matilda (Swing/Children’s Dance Captain). -

MARTIN PAKLEDINAZ, Costume Designer

THE ELIXIR OF LOVE FOR FAMILIES PRODUCTION TEAM BIOGRAPHY MARTIN PAKLEDINAZ, Costume Designer Martin Pakledinaz is an American Tony Award-winning costume designer for stage and film. His work on Broadway includes The Pajama Game, The Trip to Bountiful, Wonderful Town, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Kiss Me, Kate, The Boys From Syracuse, The Diary Of Anne Frank, A Year With Frog And Toad, The Life, Anna Christie, The Father, and Golden Child. Off-Broadway work includes Two Gentlemen of Verona, Andrew Lippa's The Wild Party, Kimberly Akimbo, Give Me Your Answer, Do, Juvenalia, The Misanthrope, Kevin Kline's Hamlet, Twelve Dreams, Waste, and Troilus and Cressida. He won two Tony Awards for designing the costumes of Thoroughly Modern Millie and the 2000 revival of Kiss Me Kate, which also earned him the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Costume Design. He has designed plays for the leading regional theatres of the United States, and the Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden. Opera credits include works at the New York Metropolitan Opera and the New York City Opera, as well as opera houses in Seattle, Los Angeles, St. Louis, Sante Fe, Houston, and Toronto. European houses include Salzburg, Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Helsinki, Gothenburg, and others. His dance credits include a long collaboration with Mark Morris, and dances for such diverse choreographers as George Balanchine, Eliot Feld, Deborah Hay, Daniel Pelzig, Kent Stowell, Helgi Tomasson, and Lila York. His collaborators in theatre include Rob Ashford, Gabriel Barre, Michael Blakemore, Scott Ellis, Colin Graham, Sir Peter Hall, Michael Kahn, James Lapine, Stephen Lawless, Kathleen Marshall, Charles Newell, David Petrarca, Peter Sellars, Bartlett Sher, Stephen Wadsworth, Garland Wright, and Francesca Zambello. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442

English 252: Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442-07-387-1551 61/63 Cartwright Gardens London, UK WC1H 9EL [*Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 28 *1:00 p.m. Beauties and Beasts. Retold by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate). Adapted by Tim Supple. Dir Melly Still. Design by Melly Still and Anna Fleischle. Lighting by Chris Davey. Composer and Music Director, Chris Davey. Sound design by Matt McKenzie. Cast: Justin Avoth, Michelle Bonnard, Jake Harders, Rhiannon Harper- Rafferty, Jack Tarlton, Jason Thorpe, Kelly Williams. Hampstead Theatre *7.30 p.m. Little Women: The Musical (2005). Dir. Nicola Samer. Musical Director Sarah Latto. Produced by Samuel Julyan. Book by Peter Layton. Music and Lyrics by Lionel Siegal. Design: Natalie Moggridge. Lighting: Mark Summers. Choreography Abigail Rosser. Music Arranger: Steve Edis. Dialect Coach: Maeve Diamond. Costume supervisor: Tori Jennings. Based on the book by Louisa May Alcott (1868). Cast: Charlotte Newton John (Jo March), Nicola Delaney (Marmee, Mrs. March), Claire Chambers (Meg), Laura Hope London (Beth), Caroline Rodgers (Amy), Anton Tweedale (Laurie [Teddy] Laurence), Liam Redican (Professor Bhaer), Glenn Lloyd (Seamus & Publisher’s Assistant), Jane Quinn (Miss Crocker), Myra Sands (Aunt March), Tom Feary-Campbell (John Brooke & Publisher). The Lost Theatre (Wandsworth, South London) Thursday December 29 *3:00 p.m. Ariel Dorfman. Death and the Maiden (1990). Dir. Peter McKintosh. Produced by Creative Management & Lyndi Adler. Cast: Thandie Newton (Paulina Salas), Tom Goodman-Hill (her husband Geraldo), Anthony Calf (the doctor who tortured her). [Dorfman is a Chilean playwright who writes about torture under General Pinochet and its aftermath.