Chapter 7: Natural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 ACWORTH COLD RIVER 111 ALBANY IONA LAKE 1 ALLENSTOWN ARCHERY POND 1 ALLENSTOWN BEAR BROOK 1 ALLENSTOWN CATAMOUNT POND 1 ALSTEAD COLD RIVER 1 ALSTEAD NEWELL POND 1 ALSTEAD WARREN LAKE 1 ALTON BEAVER BROOK 1 ALTON COFFIN BROOK 1 ALTON HURD BROOK 1 ALTON WATSON BROOK 1 ALTON WEST ALTON BROOK 1 AMHERST SOUHEGAN RIVER 11 ANDOVER BLACKWATER RIVER 11 ANDOVER HIGHLAND LAKE 11 ANDOVER HOPKINS POND 11 ANTRIM WILLARD POND 1 AUBURN MASSABESIC LAKE 1 1 1 1 BARNSTEAD SUNCOOK LAKE 1 BARRINGTON ISINGLASS RIVER 1 BARRINGTON STONEHOUSE POND 1 BARTLETT THORNE POND 1 BELMONT POUT POND 1 BELMONT TIOGA RIVER 1 BELMONT WHITCHER BROOK 1 BENNINGTON WHITTEMORE LAKE 11 BENTON OLIVERIAN POND 1 BERLIN ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 11 BRENTWOOD EXETER RIVER 1 1 BRISTOL DANFORTH BROOK 11 BRISTOL NEWFOUND LAKE 1 BRISTOL NEWFOUND RIVER 11 BRISTOL PEMIGEWASSET RIVER 11 BRISTOL SMITH RIVER 11 BROOKFIELD CHURCHILL BROOK 1 BROOKFIELD PIKE BROOK 1 BROOKLINE NISSITISSIT RIVER 11 CAMBRIDGE ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 1 CAMPTON BOG POND 1 CAMPTON PERCH POND 11 CANAAN CANAAN STREET LAKE 11 CANAAN INDIAN RIVER 11 NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 CANAAN MASCOMA RIVER, UPPER 11 CANDIA TOWER HILL POND 1 CANTERBURY SPEEDWAY POND 1 CARROLL AMMONOOSUC RIVER 1 CARROLL SACO LAKE 1 CENTER HARBOR WINONA LAKE 1 CHATHAM BASIN POND 1 CHATHAM LOWER KIMBALL POND 1 CHESTER EXETER RIVER 1 CHESTERFIELD SPOFFORD LAKE 1 CHICHESTER SANBORN BROOK -

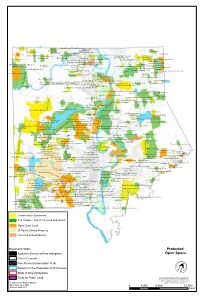

Protected Open Space

Joan and Conrad Hardy Easement Keating Property Weir Road Lot East Street Vacant Lot Weir Road Lot Penacook Park Kattar Subdivision Hyland Property Weir Road Lot Island Pond EstatesVillage Street Gazebo Maxfield Lot Allen State Forest B&M Conservation Land Malinsky Easement Dorthy Walker PropertyReno Easement Foss Easement Freedom Acres Open Space Keller Easement Bulla Property Hardy Property #2 Rolfe Park - LWCF Freedom Acres Open Space Glen Ellen Subdivsion Sally Silver Easement Penacook Street Lot Millstream Open SpaceRolfe Park - LWCF 95 Hoit Road Easement Bois de Brodeur TrustHoit Road Marsh WMA Millsteam Open Space Riley Property Merrimack Valley School District Hoit Road Marsh WMA Woodland Cemetery Laura M Jobin Family Trust Easement Primrose at Penacook Randall Property Emerald Abode Broad Cove Forest Kevin Prince Pines at Hayward BrookAcres of Wildlife Hoit Road Marsh WMA Primrose at Penacook Hoit Road Marsh WMA Emerald Abode Easement Harold Colby Easement Primrose at Penacook rk Riley Property Pa Richards Community Forest Primrose Woods ear Hoit and Shaker Road Easement Primrose Woods Sp k r Riley Property Mast Yard State Forest a P Primrose WoodsPrimrose Woods Manor Dump n Stonehaven e Oxbow Bluffs or Rust Property n i Swan Circle Subdivision t h Horse Hill Road Parcel Oxbow Subdivision Open Space e L Hot Hole Pond Boat Access Sewalls Falls State Recreation AreaFranklin Pierce Property s Carter Hill Road Easement Claremont & Concord RR Bed u G Griffin Easement Contoocook River ParcelClaremont & Concord RR BedB&M Claremont Rail -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

New Hampshire River Protection and Energy Development Project Final

..... ~ • ••. "'-" .... - , ... =-· : ·: .• .,,./.. ,.• •.... · .. ~=·: ·~ ·:·r:. · · :_ J · :- .. · .... - • N:·E·. ·w··. .· H: ·AM·.-·. "p• . ·s;. ~:H·1· ··RE.;·.· . ·,;<::)::_) •, ·~•.'.'."'~._;...... · ..., ' ...· . , ·....... ' · .. , -. ' .., .- .. ·.~ ···•: ':.,.." ·~,.· 1:·:,//:,:: ,::, ·: :;,:. .:. /~-':. ·,_. •-': }·; >: .. :. ' ::,· ;(:·:· '5: ,:: ·>"·.:'. :- .·.. :.. ·.·.···.•. '.1.. ·.•·.·. ·.··.:.:._.._ ·..:· _, .... · -RIVER~-PR.OT-E,CT.10-N--AND . ·,,:·_.. ·•.,·• -~-.-.. :. ·. .. :: :·: .. _.. .· ·<··~-,: :-:··•:;·: ::··· ._ _;· , . ·ENER(3Y~EVELOP~.ENT.PROJ~~T. 1 .. .. .. .. i 1·· . ·. _:_. ~- FINAL REPORT··. .. : .. \j . :.> ·;' .'·' ··.·.· ·/··,. /-. '.'_\:: ..:· ..:"i•;. ·.. :-·: :···0:. ·;, - ·:··•,. ·/\·· :" ::;:·.-:'. J .. ;, . · · .. · · . ·: . Prepared by ~ . · . .-~- '·· )/i<·.(:'. '.·}, •.. --··.<. :{ .--. :o_:··.:"' .\.• .-:;: ,· :;:· ·_.:; ·< ·.<. (i'·. ;.: \ i:) ·::' .::··::i.:•.>\ I ··· ·. ··: · ..:_ · · New England ·Rtvers Center · ·. ··· r "., .f.·. ~ ..... .. ' . ~ "' .. ,:·1· ,; : ._.i ..... ... ; . .. ~- .. ·· .. -,• ~- • . .. r·· . , . : . L L 'I L t. ': ... r ........ ·.· . ---- - ,, ·· ·.·NE New England Rivers Center · !RC 3Jo,Shet ·Boston.Massachusetts 02108 - 117. 742-4134 NEW HAMPSHIRE RIVER PRO'l'ECTION J\ND ENERGY !)EVELOPMENT PBOJECT . -· . .. .. .. .. ., ,· . ' ··- .. ... : . •• ••• \ ·* ... ' ,· FINAL. REPORT February 22, 1983 New·England.Rivers Center Staff: 'l'bomas B. Arnold Drew o·. Parkin f . ..... - - . • I -1- . TABLE OF CONTENTS. ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS . ~ . • • . .. • .ii EXECUTIVE -

Bradford Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018 for Adoption 11-19-18

- 2012: September Tropical Storm Irene- Flood of Fairgrounds Road (from R Herman, FD) 2018: April Wind Storm- Trees Down on Power Lines & NH 114 (from J Valiquet, PD) 2018: May Tornado EF-1- Trees Down in Bradford (from internet) Adopted by the Bradford Board of Selectmen November 19, 2018 NHHSEM/FEMA Approved____ 2018 Selectmen Adopted November 19, 2018 NHHSEM/FEMA Approved ___, 2018 Town of Bradford PO Box 436 134 East Main Street Bradford, NH 03221 Phone: (603) 938-5900 www.bradfordnh.org Central NH Regional Planning Commission (CNHRPC) 28 Commercial Street, Suite 3 Concord, NH 03301 Phone: (603) 226-6020 www.cnhrpc.org NH Department of Safety (NHDOS) NH Homeland Security and Emergency Management (NHHSEM) 33 Hazen Drive Concord, NH 03305 (Mailing Address) Incident Planning and Operations Center (IPOC) 110 Smokey Bear Blvd Concord, NH 03301 (Physical Address) Phone: (800) 852-3792 or (603) 271-2231 www.nh.gov/safety/divisions/hsem https://apps.nh.gov/blogs/hsem US Department of Homeland Security Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 99 High Street, Sixth Floor Boston, Massachusetts 02110 Phone: (617) 223-9540 www.fema.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 1 PLANNING PROCESS ................................................................................................................ 1 Certificate of Adoption, 2018 ................................................................................................................. 1 Plan Process Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... -

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES Lakesmart Program

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES LakeSmart Program Only with YOUR help will New Hampshire’s lakes remain clean and healthy, now and in the future. The health of our lakes, and our enjoyment of these irreplaceable natural resources, is at risk. Polluted runoff water from the landscape is washing into our lakes, causing toxic algal blooms that make swimming in lakes unsafe. Failing septic systems and animal waste washed off the land are contributing bacteria to our lakes that can make people and pets who swim in the water sick. Toxic products used in the home, on lawns, and on roadways and driveways are also reaching our lakes, poisoning the water in some areas to the point where fish and other aquatic life cannot survive. NH LAKES has found that most property owners don’t know how their actions affect the health of lakes. We’ve also found that property owners want to do the right thing to help keep the lakes they enjoy clean and healthy and that they often need help of professional service providers like YOU! What is LakeSmart? The LakeSmart program is an education, evaluation, and recognition program that inspires property owners to live in a lake- friendly way, keeping our lakes clean and healthy. The program is free, voluntary, and non-regulatory. Through a confidential evaluation process, property owners receive tailored recommendations about how to implement lake-friendly living practices year-round in their home, on their property, and along and on the lake. Property owners have access to a directory of lake- friendly living service providers to help them adopt lake-friendly living practices. -

Board of Selectmen Minutes

TOWN OF DEERING Board of Selectmen 762 Deering Center Road Deering, NH 03244 Meeting Minutes June 20, 2018 Selectmen present: Aaron Gill, Allen Belouin, John Shaw. The meeting was called to order at 1900. MEETING MINUTES: Meeting Minutes – June 20th. Mr. Gill made the motion to approve the June 20th meeting minutes. Mr. Belouin seconded the motion. The vote was unanimous and so moved. New Business Gary Samuels – Little Library Placement Library Trustees Gary Samuels and Betsy Holmes spoke about the concept of a “Little Free Library” explaining that they are a small, boxlike structure mounted to a post where books can be taken and returned. Given the absence of a full-time library the Trustees believed that the “Little Free Library” represented a good alternative that provided better accessibility to books and reading opportunities for the Deering community. The Board along with the two Library Trustees went outside to look at a recently constructed Little Free Library. Discussion about its location on the Town Office grounds ensued with a decision about its final placement left until consultation with the Road Agent. Handicap accessibility and snow removal being prime concerns related to its placement. Little Free Library Example Fire Department – Per Diem New Hires Fire Chief Dan Gorman introduced two new hires, Troy Normandin who is an advanced EMT and Fire Fighter, and Drew Bertolino who is a paramedic. Board members welcomed the new hires and all agreed that they will make valuable contributions to the department. Intent to Cut – Mike Mullen Mr. Gill explained to those present that Mr. -

Open Space Master Plan

SECTION VII. CONSERVATION AND OPEN SPACE A. INTRODUCTION The Conservation and Open Space Section is intended to guide the protection of the City’s natural resources and environment while promoting the appropriate and efficient use of land and water within the City of Concord in a manner consistent with the economic, physical, and social needs and desires of the citizens of Concord. Appropriate uses of open space have been identified as recreation, public service and safety, resource production, and environmental protection while providing the maximum and multi-purpose use of open space by the citizens of Concord. Open space in Concord is intended to be a system, interconnected and interrelated, and therefore, the links among major open space areas, as well as between the open areas and developed areas, must be defined The Conservation and Open Space Use Section consists of a review of existing protected lands with a focus on additions to the protected land inventory that have occurred since the last Master Plan was adopted in December 1993. Conservation and open space goals are articulated, and applied to and interpreted upon the landscape of the City, and as displayed on maps that indicate how land in Concord should be preserved and protected. Policies and recommendations to guide the implementation of the Future Open Space Plan complete this Section of the Master Plan. B. CONSERVATION AND OPEN SPACE GOALS When the City Council established the Conservation Commission in 1971, it set forth for the Commission the goal of "protecting, promoting and developing the natural resources...and for protecting the watershed resource of the City" and mandated the Conservation Commission, in conjunction with the City Planning Board, to prepare "a conservation and open space plan" as the major objective in achieving this goal, noting that the plan shall be based "on the concept of multiple use of natural resources and open space". -

Working for Clean and Healthy Lakes

NH LAKES 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Working for clean and healthy lakes ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Working for clean and healthy lakes 1 2019 ANNUAL REPORT NH LAKES 2019 Annual Report A reflection on the fiscal year ending March 31, 2019 You are NH LAKES! NH LAKES by Stuart Lord, Board Chair 17 Chenell Drive, Suite One Concord, NH 03301 603.226.0299 It has been an Everyone has a part to play! This nhlakes.org [email protected] extraordinary year for year, NH LAKES has flung the doors Board of Directors NH LAKES! Before wide open for anyone and everyone (as of March 31, 2019) you get deeper into to find their place in this rapidly- this report and read growing community of concerned Officers about all the citizens who value the beauty of New Stuart Lord (Silver Lake) programmatic Hampshire’s lakes. Chair John Edie (Meredith) accomplishments, In this report, you will see all the Vice Chair I want to try to make tangible for you different ways people of all ages have Bruce Freeman (Strafford) what is, on some levels, intangible. I’m responded to this call-to-action. We Treasurer referring to the evolution this John-Michael (JM) Girald (Rye) appreciate every pledge, contribution, Secretary organization has experienced as a story, photograph, and drawing shared Kim Godfrey (Holderness) result of the success of The Campaign for the purpose of keeping New At-Large for New Hampshire Lakes. Hampshire’s lakes clean and healthy. Board of Directors I’m talking about pride in the work we Inspired by the generosity of the 40 Reed D. -

2008 State Owned Real Property Report

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE STATE OWNED REAL PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL FINANCIAL DATA to the COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2008 STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE STATE OWNED REAL PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL FINANCIAL DATA to the COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2008 Prepared by the Department of Administrative Services Linda M. Hodgdon Commissioner Division of Accounting Services: Stephen C. Smith, CPA Administrator Diana L. Smestad Kelly J. Brown STATE OWNED REAL PROPERTY TABLE OF CONTENTS Real Property Summary: Comparison of State Owned Real Property by County........................................ 1 Reconciliation of Real Property Report to the Financial Statements............................................................. 2 Real Property Summary: Acquisitions and Disposals by Major Class of Fixed Assets............................. 3 Real Property Summary: By Activity and County............................................................................................ 4 Real Property Summary: By Town...................................................................................................................... 13 Detail by Activity: 1200- Adjutant General......................................................................................................................................... 20 1400 - Administrative Services............................................................................................................................ 21 1800 - Department of Agriculture, -

Merrimack Valley

Aì Im Aì !"`$ ?{ Aù ?x Ij ?¬ ?¬ Im Ai AÔ Aù AÔ ?x ?v !"b$ Ij AÔ AÙ Aä ?¸ !"`$ ?¨ Im AÕ A£ CÚ ?{ ?x A¢ AÖ Ij ?} ?} ?v Il ?} Aõ A¡ ?} Il Ae AÑ ?} AÙ AÑ fg ?¸ ?} ?} Aù Aä !"b$ A¡ !"`$ ?} Ij AÕ A¤ CÓ ?} CÒ Ij ?¸ AÑ ?} ?} C¹ ?{ #V Im Aõ ?¨ AÑ Aý AÙ Ij AÖ fgA B C D AÕ E F G 4 Lake Winnipesaukee d . Merrymeeting Lake Greenough Pond R ALTON BAY STATE FOREST ROLLINS STATE PARK F R A N K L I N 0 K F R A N K L I N B E L M O N T h B E L M O N T e t N 1 9 PAGE STATE FOREST a o . u Sondogardy Pond Aä 8 r r o Crystal Lake 1 th s NNOORRTTHH FFIIEE LLDD N 6 y S O N w a I . R SSAA LLIISS BB UURRYY E GG I O 6 an H r R E t STATE FOREST NURSERY R m Palmer Pond 3 S l i g 4 E S i 3v . K E G e S A K C e L A . N L k 7 n Marsh Pond 3r t 5 1 MEADOW POND STATE FOREST a r . R-11 N Suncook River F R s M o Tucker Pond 1 New Pond MERRIH MACK VALLEY REGION r Chalk Pond 3 r d Stevens Brook AÑ e o 1 t 5 1 h Forest Pond 4 u Lyford Pond . h AYERS STATE FOREST 4 0 Marchs Pond ?§ H e Shellcamp Pond n fg m r S U T T O N B i t n Merrymeeting River S U T T O N g 6 A a d a . -

Maintaining Grassmere

“Your Local Weekly Since 1868 A Tradition Worth Keeping” THE MessengerFree Our 147th Year Issue 33 August 14, 2015 Hilliard honored Attorney Russell F. Hilliard of Upton & Hatfield, LLP, became President of the National Caucus of State Bar Associations at the recent ABA Annual Meeting in Chicago. The purpose of the caucus is to coordinate the efforts of state bar associations across the country in con- sidering and proposing matters before the American Bar. He has been ranked by Chambers USA’s America’s Leading Lawyers for Business, The Best Lawyers in America® and Super Lawyers. Tina Minard paints the face of Isabel Brotherton as brothers Corwin and Anthony wait for their turns at the New Assist Principal Annual Deering Fair. Sondra Brake has been named Assistant Principal at the Weare Middle School. She replaces John Mac- Arthur, who Maintaining Grassmere is now a principal at Goffstown Selectmen question future of Hall the Boynton Middle Vice Chairman Lemay told the Goffstown enough income to make it sustain itself. If we School Selectmen that he had seen the report on the can't, what's the next best thing to preserve in New Grasmere Town Hal and there were several the building? Selectman Adams said he'd like Ipswich. areas of concern. Chairman Georgantas asked to see how much money we have put into Mrs. Brake how much it would cost and Lemay said it this already to help decide what to do next. comes would have to go out to bid. It would have to Selectman Gross said he's not sure it's a sound to the Weare Middle School from the meet the Historic Registry requirements.