Wagner-2014-Religon As Brands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friday Church News Notes

VOLUME 17, ISSUE 10 WAY OF LIFE MARCH 4, 2016 FRIDAY CHURCH NEWS NOTES THE IMMORALITY CRYSTAL SURROUNDING BIBLE TO LAST HILLSONG MUSIC BILLIONS OF Former Hillsong pastor Pasquale “Pat” Mesiti has pleaded guilty to YEARS assaulting his second wife and is awaiting sentencing (Christian Headlines, Feb. 29, 2016). He was forced to step down in 2002 because of adultery and visiting prostitutes. In an interview with Sight Researchers in the United Kingdom Magazine in May 2006, he said he had a “sexual addiction.” Tat was have developed digital data discs the year he was back in “ministry” afer divorce and remarriage and a that can survive an alleged 13 “restoration” process. He is now known as “Mr. Motivation” and billion years and can withstand promotes a “millionaire mindset” that comes from the charismatic temperatures up to 1,832 F. Te prosperity doctrine. Hillsong, a prominent voice in Contemporary data is encoded by laser onto a glass Worship, began in Australia and has branched out in recent years to disc that can hold 360 terabytes of establish megachurches in many cities, including New York and London. Te following is from a report by Hughie Seaborn titled information, which is equivalent to “Warning: What Do You Know about Hillsong?” which was published the information capacity of 25,500 in response to Hillsong’s World of Worship Conference at the Cairns basic iPhones (“Crystal Bible to last Convention Center September 4-7, 2002. Tis report by a former a billion years,” CNN, Feb. 26, Pentecostal exposes the immorality that is rampant in these circles: 2016). -

YOUR INFO! Work to Reach Every Street and Every Person for Jesus

The Mission of the Rock Church is to Save, Equip and Send. Miles McPherson is the Senior Pastor of the Rock Church and founder of DoSomethingChurch.org, a vibrant affiliation of churches around the world, dedicated to establishing Pervasive Hope in their communities through proactive Update community service. The Rock is one of the largest churches in the US and home to over 120 outreach ministries. In 2012, the Rock Church donated 233,712 hours of community service to the county of San Diego. This year, the Rock Church is expanding to include a campus in east San Diego county and continuing God’s YOUR INFO! work to reach every street and every person for Jesus. FOLLOW MILES ON TWITTER: @MILESMCPHERSON NORTH COUNTY SERVICES TIMES Name DOB Sunday • 8AM* • 10AM* • 12PM* • 5PM* *Rock Kids services are for Infants through 5th grade. Address Closed captioning at 10 am service for livestream viewers City State Zip Junior High • 10AM • 12PM • 5PM // Young Adult • 7PM // High School • 7PM (Wednesdays) For other Rock Church campuses, visit sdrock.com. Home Phone Cell RockTV: Sundays • 11PM • San Diego 6 // Rock Radio: KPRZ 1210 • M-F 4:30PM Email OTHER RESOURCES Rock Thrift Store @ rockthriftstore.com • 619.876.4187. Rockpile Bookstore & Dlush Lounge Rock Academy Campus: Pt. Loma North County rockpilebookstore.com • 619.764.5282 therockacademy.org • 619.764.5200 WASC-accredited, college preparatory Male Female Married Preschool K-12 school. therockacademy.org • 619.764.5205 Single Widow(er) Divorced Fully licensed, infant-to-5-year preschool. Need prayer? Military Police Firefighter Contact [email protected] Impact195 Name(s) and birthday(s) of household member(s): The Rock's School of Discipleship and Evangelism i195.org • 619.764.5249 HOW DID YOU HEAR ABOUT US? WAYS TO GIVE Friend or Family On the News Radio GIVE GIVE TEXT Social Media Drive By Web NOW ONLINE 2 GIVE Other Drop off your gift For fast and convenient Text or email your gift envelope in the lobby. -

There Is More Hillsong Album Downloa

There is more hillsong album downloa Continue HomeMusicHillsong Worship - There is more (Album Download) Download There's more album of today's, influential group worship Hillsong worship. The link is below. Download Hillsong Worship - There is more (live) album zip. There Is More is the 26th live album by Australian band Hillsong Worship. The album was released on April 6, 2018 by Hillsong Music and Capitol Christian Music Group. The production was handled by Brooke Ligertwood and Michael Guy Chisott. Stream and download Hillsong Worship - There's more (Live) Tsip Album 320kbps datafilehost Fakaza Descarger Torrent CD' iTunes Album below. Stream and download below. Tracklist below: Hillsong Worship - Who Do You Say I (Live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - You Are Life (Live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Passion (live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - God So Loved (Live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Be Still (Live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Memory (Live) Hillsong Worship - Touch of Heaven (Live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Writing Love (Live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Lord of Prayer (Live) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - New Wine (Live) Mp3 Hills Downloadong Worship - So I (100 Billion X) Live Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Seasons (Live) What I (Live /Acoustic) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Memory (Live / Acoustic) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Touch of Heaven (Live /Acoustic) Mp3 Download Hillsong Worship - Passion (Live/Acoustic) Mp3 Download Tzip You are currently listening to samples. Listen to more than 60 million songs with an unlimited streaming plan. Listen to this album and over 60 million songs with unlimited streaming plans. 1 month free, then 19.99 euros/month in Genesis 32 we read the story of Jacob fighting God for the night. -

Devotional Thoughts for Your Global 6K » a 6-Week Training Companion

Luke, age 8, USA Kamama, age 5, Kenya Devotional thoughts for your Global 6K » a 6-week training companion Cheru, age 5, Kenya Week One » Day 1 Starting anything new can be daunting: breaking in those fresh-outta-the-box sneakers, changing up your schedule to fit training in, and planning meals to fuel your workouts. Congratulations! You’ve started a training journey with a community of like-minded Christ-followers around the world, aimed at one thing—bringing clean water to people who don’t have it. There’s a significant beginning recorded in the Bible. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth … and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters” (Genesis 1:1-2). Meditate today on this passage and how water was an important part of the Creation story. And think about how the Spirit of God will empower your training— beginning today. » Day 2 If we’re honest, we’ll admit there are lots of things we don’t know. For instance, we don’t really know what it’s like to journey miles for clean water because it’s piped in to our homes. But after you’ve walked or run the Global 6K for Water, you’ll have a slight taste of the experience. Here’s another thing you may not know (or remember). The Bible says in 1 Corinthians 6:19, “Do you not know that your bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit …?” What a great insight! No matter its shape, your body holds God’s presence—and that’s something to celebrate. -

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia Hillsong Church Annual Report 2 Index

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia 2 Annual Report Hillsong Church Index Chairperson’s Report 4 The Church I Now See 5 Lead Pastor’s Report 6 General Manager’s Report 7 History 8 Church Services 10 Programs & Services 12 Children 14 Youth 16 Women 18 Young at Heart 20 Pastoral Care 22 Volunteers 24 Creative Arts 26 Worship 28 Conferences 30 Missions 32 Education 34 Local Community Services 36 Overseas Aid & Development 42 The Hillsong Foundation 46 Two Thousand & Fourteen Two Our Board 48 Financial Reports 51 “I see a church Governance 58 that beckons WELCOME HOME to every man, woman and child that walks through the doors.” – Brian Houston (The Church I Now See) 3 Chairperson’s Report Brian & Bobbie Houston As we reflect on the year past, we can truly thank God for His We have now been holding Hillsong Conference since 1986 unwavering goodness and love for humanity. God specialises with the mission: Championing the cause of local churches in lifting people out of tragedy and pain, rebuilding hope and everywhere. With over 22,000 attendees and 19 Christian restoring us to a friendship with Him. denominations represented we celebrate the diversity of the expressions of our faith and gather around the common We as a church are privileged to play our role in seeing lives understanding that a healthy local church can make a positive impacted through the Gospel of Jesus Christ. At Hillsong impact in its community. Church, hundreds of people make a decision to follow Christ each week, a foundational step on a journey of personal It is with this understanding we are enthusiastic about freedom and understanding. -

Gospel with a Groove

Southeastern University FireScholars Selected Honors Theses Spring 4-28-2017 Gospel with a Groove: A Historical Perspective on the Marketing Strategies of Contemporary Christian Music in Relation to its Evangelistic Purpose with Recommendations for Future Outreach Autumn E. Gillen Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: http://firescholars.seu.edu/honors Part of the Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Marketing Commons, Music Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Gillen, Autumn E., "Gospel with a Groove: A Historical Perspective on the Marketing Strategies of Contemporary Christian Music in Relation to its Evangelistic Purpose with Recommendations for Future Outreach" (2017). Selected Honors Theses. 76. http://firescholars.seu.edu/honors/76 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOSPEL WITH A GROOVE: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE MARKETING STRATEGIES OF CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC IN RELATION TO ITS EVANGELISTIC PURPOSE WITH RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE OUTREACH by Autumn Elizabeth Gillen Submitted to the Honors Program Committee in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors Scholars Southeastern University 2017 GOSPEL WITH A GROOVE 2 Copyright by Autumn Elizabeth Gillen 2017 GOSPEL WITH A GROOVE 3 Abstract Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) is an effective tool for the evangelism of Christianity. With its origins dating back to the late 1960s, CCM resembles musical styles of popular-secular culture while retaining fundamental Christian values in lyrical content. This historical perspective of CCM marketing strategies, CCM music television, CCM and secular music, arts worlds within CCM, and the science of storytelling in CCM aims to provide readers with the context and understanding of the significant role that CCM plays in modern-day evangelism. -

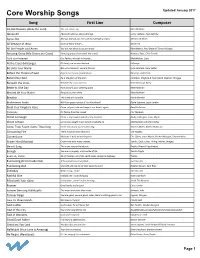

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer

Core Worship Songs Updated January 2017 Song First Line Composer 10,000 Reasons (Bless the Lord) The sun comes up, Matt Redman Above All Above all nations, above all kings Lenny LeBlanc, Paul Baloche Agnus Dei Alleluia, alleluia, for the Lord God Almighty reigns Michael W Smith All because of Jesus Giver of every breath… Steve Fee All the People said Amen You are not alone if you are lonely Matt Maher, Paul Moak & Trevor Morgan Amazing Grace (My Chains are Gone) Amazing grace, how sweet the sound Newton, Rees, Chris Tomlin As it is in heaven Our Father, who art in heaven… Matt Maher, Cash At the Cross (Hillsongs) Oh Lord, you've searched me Hillsongs Be Unto Your Name We are a moment, you are forever Lynn DeShazo, Gary Sadler Before the Throne of God Before the throne of God above Bancroft, Vicki Cook Behold Our God He is the glory of the stars Jonathan, Meghan & Ryan Baird, Stephen Altrogge Beneath the Cross Beneath the cross of Jesus Keith & Kristyn Getty Better Is One Day How lovely is your dwelling place Matt Redman Blessed Be Your Name Blessed be your name Matt Redman Breathe This is the air I breathe Marie Barnett Brokenness Aside Will Your grace run out if I let You down? David Leonard, Leslie Jordan Build Your Kingdom Here Come set your rule and reign in our hearts again Rend Collective Cannons It's falling from the clouds Phil Wyckam Christ is Enough Christ is my reward and all of my devotion Reuben Morgan, Jonas Myrin Christ is Risen Let no one caught in sin remain insidethe lie Matt Maher and Mia Fieldes Come Thou Fount, Come -

February 2004

VOLUME 31/1 FEBRUARY 2004 “Do you not give the horse his strength or clothe his neck with a flowing mane?” Job 39:19 faith in focus Volume 31/1, February 2004 CONTENTS Editorial Whose party are you going to? Uncovering a very present danger 3 It was some years ago that a minister was overhearing several colleagues at a minister’s conference speaking about several high-powered revival meetings Not satisfied with Jesus? When faith is not alone 7 they had experienced. They spoke in glowing terms of how warmly they felt and how much everyone there shared a wonderful spiritual unity. Sons of encouragement 8 This minister shared with them his own experience of a meeting he had come World News 9 from the night before he flew over. He detailed the feelings he had when over Breakthrough 40,000 sang the same songs, held hands, and came away with a truly The lesson in life 11 unforgetable event. Missions in focus His colleagues now were completely captivated by his story. This was something Growing the church in Karamoja extraordinary. And to hear all this from this man who otherwise you would think Prayer points RCNZ food aid to Malawi 12 was the last to be open to such a move of the Spirit! They had to ask him who was the cause for this incredible time. Which special person’s meeting was it? Surfing the Net The upside & downside of the Internet 15 “Oh,” the minister replied, “it was a Paul McCartney concert.” Naturally, those ministers felt somewhat taken in. -

Pentecostal Pastorpreneurs and the Global Circulation of Authoritative Aesthetic Styles

Culture and Religion An Interdisciplinary Journal ISSN: 1475-5610 (Print) 1475-5629 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcar20 Pentecostal pastorpreneurs and the global circulation of authoritative aesthetic styles Miranda Klaver To cite this article: Miranda Klaver (2015) Pentecostal pastorpreneurs and the global circulation of authoritative aesthetic styles, Culture and Religion, 16:2, 146-159, DOI: 10.1080/14755610.2015.1058527 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2015.1058527 Published online: 14 Jul 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 335 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcar20 Download by: [Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam] Date: 30 October 2017, At: 06:47 Culture and Religion, 2015 Vol. 16, No. 2, 146–159, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2015.1058527 Pentecostal pastorpreneurs and the global circulation of authoritative aesthetic styles Miranda Klaver* Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, VU University Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands This article argues that the rise of ‘pastorpreneurs’ in global neo- Pentecostalism calls for an aesthetic perspective on religious authority and leadership in the context of new media. Different from mainline churches, religious leadership in neo-Pentecostal (In many parts of the world, neo-Pentecostal or new Pentecostal churches have emerged since the 1980s. They are usually independent churches, organized in loose national or transnational networks, Anderson 2004) churches is not legitimised by denominational traditions and the ordination of clergy but by ‘pastorpre- neurs’, (Twitchell uses the term pastorpreneurs to describe megachurch pastors who by using marketing techniques and other entrepreneurial business skills create stand-alone religious communities that challenge top- down denominationalism (2007:3). -

INDUSTRY Q&A: Steve Mcpherson, Manager, Hillsong Music Publishing

WHAT’S INSIDE: INDUSTRY Q&A: Q&A with Steve McPherson, Manager, Steve McPherson, Manager, Hillsong Music Publishing Hillsong Music Publishing News By CCM Magazine Managing Editor, Celebrations Kevin Sparkman and Milestones Church bodies creating their own musical elements, Radio Movement arrangements, and even songs, isn’t really that new of a concept. One of the first congregations Appearances to embark on publishing and making their in Film/TV songs known the globe over, Australia’s Hillsong Church blazed the trail and Steve McPherson has Top Adult been there from the start. With a keen sense of Contemporary Songs ministry on a localized level, initially serving at Hillsong in youth ministry and on worship teams, Top Gospel Songs McPherson has taken his twenty-five year-plus career to now serve the Church through music on Top Rock Songs a worldwide scale. We take a few moments to chat with McPherson about the music, milestones, and Overall Chart Toppers ministry, as well as a little more about him on a personal level (Ever wondered what a guy like him Top Artists jams to while cruising the Sydney streets?) on Social Media Steve McPherson (Continued on page 3) Movement NEWS the current cover artists for the Jun. 15th with hip hop artist Blake Whitely and edition of CCM Magazine. speaker Clayton Jennings. Hillsong UNITED’s sixth studio album John Butler, former Wonder debuted VP of Promotions at at No. 1 and No. 5 on Curb Records, began the iTunes Christian his role as the head and Overall charts. of Christian Music Garnering immediate at Spotify in late April. -

Transnational Pentecostal Connections: an Australian Megachurch and a Brazilian Church in Australia Introduction I Arrived at Th

Transnational Pentecostal Connections: an Australian Megachurch and a Brazilian Church in Australia Introduction1 I arrived at the Comunidade Nova Aliança (CNA) church on a Sunday, a little bit before the 7 pm service. From the street I could hear loud music playing. When I crossed the front door I unexpectedly found myself in a nightclub: the place was dark, lit only by strobe lights, and there was a stage with large projection screens on each side. People were chatting animatedly in the adjacent foyer. They were all young, mostly in their late teens. A young woman came to chat and asked if I were okay, if I knew anyone. Prompted by me, she took me to pastor Henrique and his wife, Denise, whom I had spoken to on the phone the previous Sunday. We exchanged pleasantries and they excused themselves because service was about to start. We all moved on to the audience seats and five young people climbed onto the stage. There were three young males (a guitar and a bass players, and a drummer) and two female singers. Pastor Henrique asked the crowd in Portuguese: “Who wants to be blessed by God?” Everyone raised their arms and replied “yes”. The band started playing worship music. For an hour there was one song praising Jesus after another. Songs were in Portuguese but real-time telecasts of the band and the song lyrics translated into English were beamed onto the screens beside the stage. Everyone was dancing and singing together with the band. Many raised their arms, some kept their eyes closed, others were crying with their hands on their hearts, a few dropped to their knees overwhelmed by emotion. -

![[Article] Aboriginal Australian Pentecostals Taking the Initiative in Mount Druitt’S Urban Songlines TANYA RICHES Tanya Riches Is a Ph.D](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7325/article-aboriginal-australian-pentecostals-taking-the-initiative-in-mount-druitt-s-urban-songlines-tanya-riches-tanya-riches-is-a-ph-d-1507325.webp)

[Article] Aboriginal Australian Pentecostals Taking the Initiative in Mount Druitt’S Urban Songlines TANYA RICHES Tanya Riches Is a Ph.D

[Article] Aboriginal Australian Pentecostals taking the initiative in Mount Druitt’s urban songlines TANYA RICHES Tanya Riches is a Ph.D. student at Fuller Theological Seminary, currently investigating worship and social engagement practices of Aboriginal-led congregations in Australia from a missiological frame. Her previous M.Phil. study addressed the global expansion of Australia's Hillsong Church, and is entitled Shout to the Lord! Music and Change at Hillsong: 1996–2007. A well- known singer/songwriter in Australia, Tanya seeks creative ways of illuminating the lived experiences of those at the margins of the worship community. Her first solo album, Grace, was released in 2012. It was composed ecumenically with Christian songwriters in Sydney, and was inspired by listening to the experiences of people with disability. She regularly tours regional and transnational Pentecostal communities, including, most recently, Sicily and Malaysia. In this article I outline a renegotiation of identity boundaries as observed within the musical performance of Initiative Church, an Indigenous-led urban Pentecostal church in the suburb of Mount Druitt, Sydney, Australia, which performs under the name “Mount Druitt Indigenous Choir.” The group’s engagement with its various “others” is evident from its appeal to traditional Indigenous eldership accountability, and its location within a Pentecostal Christian religious identity. Language use and integration of culturally charged identity- markers, however, provide a subversive method of communicating both resistance and reconciliation to dominant culture holders, as music becomes a common point of intersection between various “others”: local Dharug nation elders; nearby dominant-culture Pentecostal congregations; Australian mega-churches, such as Hillsong, that disseminate music; and their North American Pentecostal counterparts, such as Bethel Church in Redding, California.