{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Friendship Films: a Post-Feminist Examination Of

FEMALE FRIENDSHIP FILMS: A POST-FEMINIST EXAMINATION OF REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN THE FASHION INDUSTRY Gülin Geloğulları UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by the Thesis Committee: Dr. George S. Larke-Walsh Dr. Jacqueline Vickery Dr. Sandra L. Spencer Geloğulları, Gülin. Female Friendship Films: A Post-Feminist Examination of Representations of Women in the Fashion Industry. Master of Arts (Radio, Television, and Film), December 2015, 101 pp., references, 56 titles. This thesis focuses on three fashion industry themed female friendship films: Pret-a- Porter/Ready to Wear (1994) by Robert Altman, The Devil Wears Prada (2006) by David Frankel, and The September Issue (2009) by R.J. Cutler. Female interpersonal relationships are complex – women often work to motivate, encourage and transform one another but can just as easily use tactics like intimidation, manipulation, and exploitation in order to save their own jobs and reputations. Through the lens of post-feminist theory, this thesis examines significant female interpersonal relationships in each film to illustrate how femininity is constructed and driven by consumer culture in the fashion industry themed films. Copyright 2015 by Gülin Geloğulları ii This thesis is dedicated to my first playmate, best friend, bodyguard, guardian angel, dreamcatcher, teacher, academic adviser, mentor, bank, real hero and brother: Dr. Cumhur Alper Geloğulları. I will be eternally grateful to you for making my life wonderful. I love you my dear brother; without your support I wouldn’t be the person I am today. Thank you, Abicim. Many Thanks to: My parents, thesis committee members, UNT Toulouse Graduate School mentors and staff members, UNT Thesis Boot Camp Committee, UNT-International Family, UNT and Denton Community, Rotary International, Rotary District 5790 and 2490. -

A Transsexual Woman-Centric Critique of Alice Dreger’S “Scholarly History” of the Bailey Controversy

1 The following essay is a “peer commentary” on Alice Dreger’s article “The Controversy Surrounding The Man Who Would Be Queen: A Case History of the Politics of Science, Identity, and Sex in the Internet Age.” Both Dreger’s article and my commentary will appear in the same upcoming issue of the journal Archives of Sexual Behavior. for the time being, this paper should be cited as: Serano, J. (in press). A Matter of Perspective: A Transsexual Woman-Centric Critique of Alice Dreger’s “Scholarly History” of the Bailey Controversy. Archives of Sexual Behavior. © 2008 Springer Science; reprinted with permission *************** A Matter of Perspective: A Transsexual Woman-Centric Critique of Alice Dreger’s “Scholarly History” of the Bailey Controversy by Julia Serano As someone who is both an academic scientist and a transsexual woman and activist, I would very much welcome a proper historical analysis of the controversy over J. Michael Bailey’s book The Man Who Would Be Queen: one that fully explores the many ethical issues raised by both the book and the backlash that ensued, one that thoughtfully articulates the perspectives of both researchers/gatekeepers and their transsexual subjects/clients while taking into consideration the institutionalized power that the former group holds over the latter. On paper, Alice Dreger seems well suited for the task given her experience as a science historian, ethicist and an advocate for sexual minorities in her past work with the Intersex Society of North America. Unfortunately, while Dreger describes her article “The Man Who Would Be Queen: A Case History of the Politics of Science, Identity, and Sex in the Internet Age” as a “scholarly history,” it fails in this regard for numerous reasons, several of which I will address here. -

Resavoring Cannibal Holocaust As a Mockumentary

hobbs Back to Issue 7 "Eat it alive and swallow it whole!": Resavoring Cannibal Holocaust as a Mockumentary by Carolina Gabriela Jauregui ©2004 "The worst returns to laughter" Shakespeare, King Lear We all have an appetite for seeing, an appétit de l'oeuil as Lacan explains it: it is through our eyes that we ingest the Other, the world.1 And in this sense, what better way to introduce a film on anthropophagy, Ruggero Deodato's 1979 film, Cannibal Holocaust, than through the different ways it has been seen.2 It seems mankind has forever been obsessed with the need to understand the world through the eyes, with the need for visual evidence. From Thomas the Apostle, to Othello's "ocular proof," to our television "reality shows," as the saying goes: "Seeing is believing." We have redefined ourselves as Homo Videns: breathers, consumers, dependants, and creators of images. Truth, in our society, now hinges on the visual; it is mediated by images. Thus it is from the necessity for ocular proof that Cinéma Vérité, Direct Cinema, documentary filmmaking and the mockumentary or mock-documentary genre stem. It is within this tradition that the Italian production Cannibal Holocaust inserts itself, as a hybrid trans-genre film. To better understand this film, I will not only look at it as a traditional horror film, but also as a contemporary mockumentary satire that presents itself as "reality" and highlights the spectator’s eye/I’s primal appetite. In the manner of Peter Watkins' film Culloden, Deodato's film is intended to confuse the audience's -

Crossdressing Cinema: an Analysis of Transgender

CROSSDRESSING CINEMA: AN ANALYSIS OF TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION IN FILM A Dissertation by JEREMY RUSSELL MILLER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2012 Major Subject: Communication CROSSDRESSING CINEMA: AN ANALYSIS OF TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION IN FILM A Dissertation by JEREMY RUSSELL MILLER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, Josh Heuman Aisha Durham Committee Members, Kristan Poirot Terence Hoagwood Head of Department, James A. Aune August 2012 Major Subject: Communication iii ABSTRACT Crossdressing Cinema: An Analysis of Transgender Representation in Film. (August 2012) Jeremy Russell Miller, B.A., University of Arkansas; M.A., University of Arkansas Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joshua Heuman Dr. Aisha Durham Transgender representations generally distance the transgender characters from the audience as objects of ridicule, fear, and sympathy. This distancing is accomplished through the use of specific narrative conventions and visual codes. In this dissertation, I analyze representations of transgender individuals in popular film comedies, thrillers, and independent dramas. Through a textual analysis of 24 films, I argue that the narrative conventions and visual codes of the films work to prevent identification or connection between the transgender characters and the audience. The purpose of this distancing is to privilege the heteronormative identities of the characters over their transgender identities. This dissertation is grounded in a cultural studies approach to representation as constitutive and constraining and a positional approach to gender that views gender identity as a position taken in a specific social context. -

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

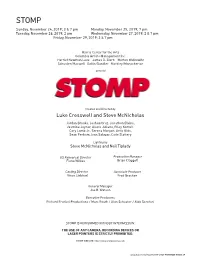

Luke Cresswell and Steve Mcnicholas

STOMP Sunday, November 24, 2019; 3 & 7 pm Monday, November 25, 2019; 7 pm Tuesday, November 26, 2019; 2 pm Wednesday, November 27, 2019; 2 & 7 pm Friday, November 29, 2019; 2 & 7 pm Harris Center for the Arts Columbia Artists Management Inc. Harriet Newman Leve James D. Stern Morton Wolkowitz Schuster/Maxwell Gallin/Sandler Markley/Manocherian present Created and Directed by Luke Cresswell and Steve McNicholas Jordan Brooks, Joshua Cruz, Jonathon Elkins, Jasmine Joyner, Alexis Juliano, Riley Korrell, Cary Lamb Jr., Serena Morgan, Artis Olds, Sean Perham, Ivan Salazar, Cade Slattery Lighting by Steve McNicholas and Neil Tiplady US Rehearsal Director Production Manager Fiona Wilkes Brian Claggett Casting Director Associate Producer Vince Liebhart Fred Bracken General Manager Joe R. Watson Executive Producers Richard Frankel Productions / Marc Routh / Alan Schuster / Aldo Scrofani STOMP IS PERFORMED WITHOUT INTERMISSION. THE USE OF ANY CAMERA, RECORDING DEVICES OR LASER POINTERS IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. STOMP WEBSITE: http://www.stomponline.com www.harriscenter.net 2019-2020 PROGRAM GUIDE 27 STOMP continued STOMP, a unique combination of percussion, movement and to Germany, Holland and France. Another STOMP production visual comedy, was created in Brighton, UK, in the summer of opened in San Francisco in May 2000, running for two and a 1991. It was the result of a ten-year collaboration between its half years. creators, Luke Cresswell and Steve McNicholas. The original cast of STOMP has recorded music for the Tank They first worked together in 1981, as members of the street Girl movie soundtrack and appeared on the Quincy Jones band Pookiesnackenburger and the theatre group Cliff Hanger. -

Top 10 Sa Music 'Media Edia

MUSIC TOP 10 SA MUSIC 'MEDIA EDIA UNITED KINGDOM GERMANY FRANCE ITALY Singles Singles Singles Singles 1 Queen Bohemian Rhapsody/These Are.. (Parlophone) 1 U 96 - Das Boot 1 (Polydor) J.P. Audin/D. Modena - Song Of Ocarina (Delphine) 1 Michael Jackson - Black Or White (Sony Music) 2 Wet Wet Wet - Goodnight Girl (Precious) 2 Michael Jackson - Black Or White (Sony Music) 2 Patrick Bruel - Qui A Le Droit (RCA) 2 G.Michael/E.John - Don't Let The Sun...(Sony Music) 3 The Prodigy - Everybody In The Place (XL) 3 Salt -N -Pepe - Let's Talk About Sex (Metronome) 3 Michael Jackson - Black Or White (Epic) 3 R.Cocciante/P.Turci - E Mi Arriva II Mare (Virgin) 4 Ce Ce Peniston - We Got A Love Thong )ABM) 4 Nirvana - Smells Like Teen Spirit (BMG) 4 Mylene Farmer - Je T'Aime Melancolie (Polydor) 4 Hammer - 2 Legit 2 Quit (EMI) 5 Kiss - God Gave Rock & Roll To ... (Warner Brothers) 5 Monty Python - Always Look On The... (Virgin) 5 Frances Cabrel - Petite Marie (Columbia) 5 D.J. Molella - Revolution (Fri Records) 6 Wonder Stuff - Welcome To The Cheap Seats (Polydor) 6 G./Michael/EJohn - Don't Let The Sun... (Sony Music) 6 Bryan Adams -I Do It For You (Polydor) 6 Bryan Adams -I Do It For You (PolyGram) 7 Kym Sims - Too Blind To See It (east west) 7 Genesis - No Son Of Mine (Virgin) 7Indra - Temptation (Carrere) 7 49ers - Move Your Feet (Media) 8 Des'ree - Feel So High (Dusted Sound) 8 Rozalla - Everybody's Free (Logic) 8 Dorothee - Les Neiges De L'Himalaya (Ariola) 8 LA Style -James Brown Is Dead (Ariola) 9 Kylie Minogue - Give Me A Little (PWL) 9 KLI/Tammy Wynette -Justified.. -

Army of Lovers Les Greatest Hits Mp3, Flac, Wma

Army Of Lovers Les Greatest Hits mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Les Greatest Hits Country: Sweden Style: Leftfield, Euro House, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1904 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1746 mb WMA version RAR size: 1295 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 648 Other Formats: AC3 ADX MP3 MP4 DMF AC3 TTA Tracklist Hide Credits 1 –Army Of Lovers Give My Life 3:55 2 –Army Of Lovers Venus And Mars 3:31 3 –Army Of Lovers My Army Of Lovers 3:27 4 –Army Of Lovers Ride The Bullet 3:27 5 –Army Of Lovers Supernatural 3:57 6 –Army Of Lovers Crucified 3:33 7 –Army Of Lovers Obsession 3:41 8 –Army Of Lovers Candyman Messiah 3:09 9 –Army Of Lovers Judgement Day 3:57 10 –La Camilla Everytime You Lie 3:12 11 –Army Of Lovers Israelism 3:21 12 –Army Of Lovers La Plage De Saint Tropez 3:31 13 –Army Of Lovers I Am 3:54 Lit De Parade 14 –Army Of Lovers 3:26 Featuring [Uncredited] – Big Money 15 –Army Of Lovers Sexual Revolution 3:58 16 –Army Of Lovers Life Is Fantastic (The 1995 Remix) 4:00 17 –Army Of Lovers King Midas 3:56 18 –Army Of Lovers Requiem 4:31 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal Music AB Notes Track 10 'Everytime You Lie' is in fact not an Army Of Lovers song, but a solo track from La Camilla. However, this is not mentioned on the sleeve. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Stockholm 529 135-2, Army Of Les Greatest Hits 529 135-2, Records, Europe 1995 529135-2 Lovers (CD, Comp) 529135-2 Stockholm Records Greatest Hits Army Of 074 (Cass, Comp, Audio Max 074 Poland Unknown -

Gravitonas Is a Stockholm-Based Band in the Electro/Dance/Rock

Gravitonas is a Stockholm-based band in the electro/dance/rock genre, fronted by lead vocalist Andreas Öhrn and celebrated record producer Alexander Bard, who work closely together with co- producer and co-writer Henrik Wikström and guitar virtuoso Ben Smith. Gravitonas was formed in 2010 An initial single and video called “Kites” was released in April 2010 and instantly became a Top 5 Club Chart hit in Sweden as well as one of the most talked about tracks on international music blogs. A four-track EP called "The Hypnosis EP" was released in September 2010. Lead track and video "Religious" quickly became a massive airplay and a Top 10 club chart hit in Russia (with over 100,000 accumulated radio spins in early 2011). “Religious” then entered the Billboard Magazine Club Play Chart in the United States in March, 2011 as an import-only release and peaked a few weeks later at #28. It also went straight to #1 on the Swedish iTunes Album Dance genre list. A four-track EP called "The Coliseum EP" was released in November 2010 with the ballad “You Break Me Up” as lead single and video which became a major radio airplay hit in Sweden. The single “Everybody Dance”, is a dance-pop collaboration with Russian electronica star Roma Kenga The track quickly became a Russian Top 10 club and music TV video hit and soon entered the Russian Top 50 Airplay chart. It also entered top 20 on the Billboard Magazine Club Play Chart and peaked at #18! The U.S. release “Everybody Dance/Religious U.S. -

PRESS KIT Baby Daddy OVERVIEW

PRESS KIT Baby Daddy OVERVIEW FILM TITLE ALEC MAPA: BABY DADDY SYNOPSIS Actor and comedian Alec Mapa (America's Gaysian Sweetheart) shares hilarious and heartfelt stories about how his life has changed since he and his husband adopted a five year old through the foster care system. No topic is off limits in this raunchy yet moving film of his award-winning one-man show: Alec's sex life, hosting gay porn award shows, midlife crisis, musical theatre, reality television, bodily functions, stage moms vs. baseball dads, and the joys, challenges, and unexpected surprises of fatherhood. Includes behind-the-scenes footage of his family's home life on a busy show day. " / / Thought Moment Media Mail: 5419 Hollywood Blvd Suite C-142 Los Angeles, CA 90027 Phone: 323-380-8662 Jamison Hebert | Executive Producer [email protected] Andrea James | Director [email protected] / Ê " TRT: 78 minutes Exhibition Format: DVD, HDCAM Aspect Ratio: 16:9 or 1.85 Shooting Format: HD Color, English ," -/ÊEÊ -/, 1/" Ê +1, - For all inquiries, please contact Aggie Gold 516-223-0034 [email protected] -/6Ê- , Ê +1, - For all inquiries, please contact Jamison Hebert 323-380-8662 [email protected] /"1/Ê" /Ê ÊÊUÊÊ/"1/" /° "ÊÊUÊÊÎÓÎÎnänÈÈÓÊÊ Baby Daddy KEY CREDITS Written and Performed by ALEC MAPA Directed by ANDREA JAMES Executive Producers JAMISON HEBERT ALEC MAPA ANDREA JAMES Director of Photography IAN MCGLOCKLIN Original Music Composed By MARC JACKSON Editors ANDREA JAMES BRYAN LUKASIK Assistant Director PATTY CORNELL Producers MARC CHERRY IAN MCGLOCKLIN Associate Producers BRIELLE DIAMOND YULAUNCZ J. DRAPER R. MICHAEL FIERRO CHRISTIAN KOEHLER-JOHANSEN JIMMY NGUYEN MARK ROSS-MICHAELS MICHAEL SCHWARTZ & MARY BETH EVANS RICHARD SILVER KAREN TAUSSIG Sound Mixer and Sound Editor SABI TULOK Stage Manager ERIKA H. -

Teacher and Student Resource Pack Lord of the Flies Teacher and Student Resource Pack 1 1

A NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE PRODUCTION TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 1 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK p3 2. WILLIAM GOLDING’S NOVEL p4 William Golding and Lord of the Flies Novel’s Plot Characters Themes and Symbols 3. NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE’S LORD OF THE FLIES p11 An Introduction By Matthew Bourne Production Research Some Initial Ideas Plot Sections Similarities and Differences 4. PRODUCTION ELEMENTS p21 Set and Costume Costume Supervisor Music Lighting 5. PRACTICAL WORKSHEETS p26 General Notes Character Devising and Developing Movement 6. REFLECTING AND REVIEWING p32 Reviewing live performance Reviews and Editorials for New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s Production of Lord of the Flies 7. FURTHER WORK p32 Did You Know? It’s An Adventure Further Reading Essay Questions References Contributors LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 2 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK This pack aims to give teachers and students further understanding of New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s production of Lord of the Flies. It contains information and materials about the production that can be used as a stimulus for written work, discussion and practical activities. There are worksheets containing information and resources that can be used to help build your own lesson plans and schemes of work based on Lord of the Flies. This pack contains subject material for Dance, Drama, English, Design and Music. Discussion and/or Evaluation Ideas Research and/or Further Reading Activities Practical Tasks Written Work The symbols above are to guide you throughout this pack easily and will enable you to use this guide as a quick reference when required. -

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) Warsaw 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Justyna Fruzińska, Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Łukasz Muniowski, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Ewa Antoszek, Edyta Frelik, Elżbieta Klimek-Dominiak, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Tadeusz Pióro, Elżbieta Rokosz-Piejko, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Stefan Schubert, Joanna Ziarkowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Vegas Options” from the series “Las Vegas.” By permission. www.flickr/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733-9154 eISSN 2544-8781 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02-653 Warsaw paas.org.pl Nakład 110 egz. Wersją pierwotną Czasopisma jest wersja drukowana. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents ARTICLES Justyna Włodarczyk Beyond Bizarre: Nature, Culture and the Spectacular Failure of B.F. Skinner’s Pigeon-Guided Missiles .......................................................................... 5 Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s ................................................................ 19 Arkadiusz Misztal Dream Time, Modality, and Counterfactual Imagination in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon ............................................................................... 37 Ewelina Bańka Walking with the Invisible: The Politics of Border Crossing in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway: A True Story .............................................