PSALMS to STRANGE TUNES Psalms 22, 45, 58, 60, 69, 75, 80, 88

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm 60-64 Monday 22Nd June - Psalm 60

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 60-64 Monday 22nd June - Psalm 60 For the director of music. To the tune of “The 6 God has spoken from his sanctuary: Lily of the Covenant.” A miktam of David. For “In triumph I will parcel out Shechem teaching. When he fought Aram Naharaim and and measure off the Valley of Sukkoth. Aram Zobah, and when Joab returned and 7 Gilead is mine, and Manasseh is mine; struck down twelve thousand Edomites in the Ephraim is my helmet, Valley of Salt. Judah is my scepter. 8 Moab is my washbasin, You have rejected us, God, and burst upon us; on Edom I toss my sandal; you have been angry—now restore us! over Philistia I shout in triumph.” 2 You have shaken the land and torn it open; 9 Who will bring me to the fortified city? mend its fractures, for it is quaking. Who will lead me to Edom? 3 You have shown your people desperate times; 10 Is it not you, God, you who have now rejected you have given us wine that makes us stagger. us 4 But for those who fear you, you have raised a and no longer go out with our armies? banner 11 Give us aid against the enemy, to be unfurled against the bow. for human help is worthless. 5 Save us and help us with your right hand, 12 With God we will gain the victory, that those you love may be delivered. and he will trample down our enemies. It seems that this Psalm is written against the backdrop of Israel’s army being defeated in the final days of Saul’s reign. -

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72 was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. ". there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."2 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. As with some of the added and updated material in the historical books, the Holy Spirit evidently led editors to add material that the original writer did not include. -

80 Days in the Psalms (Summer 2016)

80 Days in the Psalms (Summer 2016) June 16 Psalm 1, 2 July 6 Psalm 40, 41 July 26 Psalm 80, 81 August 15 Psalm 119 June 17 Psalm 3, 4 July 7 Psalm 42, 43 July 27 Psalm 82, 83 August 16 Psalm 119 June 18 Psalm 5, 6 July 8 Psalm 44, 45 July 28 Psalm 84, 85 August 17 Psalm 119 June 19 Psalm 7, 8 July 9 Psalm 46, 47 July 29 Psalm 86, 87 August 18 Psalm 119 June 20 Psalm 9, 10 July 10 Psalm 48, 49 July 30 Psalm 88, 89 August 19 Psalm 120, 121 June 21 Psalm 11, 12 July 11 Psalm 50, 51 July 31 Psalm 90, 91 August 20 Psalm 122, 123 June 22 Psalm 13, 14 July 12 Psalm 52, 53 August 1 Psalm 92, 93 August 21 Psalm 124, 125 June 23 Psalm 15, 16 July 13 Psalm 54, 55 August 2 Psalm 94, 95 August 22 Psalm 126, 127 June 24 Psalm 17, 18 July 14 Psalm 56, 57 August 3 Psalm 96, 97 August 23 Psalm 128, 129 June 25 Psalm 19, 20 July 15 Psalm 58, 59 August 4 Psalm 98, 99 August 24 Psalm 130, 131 June 26 Psalm 21, 22 July 16 Psalm 60, 61 August 5 Psalm 100, 101 August 25 Psalm 132, 133 June 27 Psalm 23, 23 July 17 Psalm 62, 63 August 6 Psalm 102, 103 August 26 Psalm 134, 135 June 28 Psalm 24, 25 July 18 Psalm 64, 65 August 7 Psalm 104, 105 August 27 Psalm 136, 137 June 29 Psalm 26, 27 July 19 Psalm 66, 67 August 8 Psalm 106, 107 August 28 Psalm 138, 139 June 30 Psalm 28, 29 July 20 Psalm 68, 69 August 9 Psalm 108, 109 August 29 Psalm 140, 141 July 1 Psalm 30, 31 July 21 Psalm 70, 71 August 10 Psalm 110, 111 August 30 Psalm 142, 143 July 2 Psalm 32, 33 July 22 Psalm 72, 73 August 11 Psalm 112, 113 August 31 Psalm 144, 145 July 3 Psalm 34, 35 July 23 Psalm 74, 75 August 12 Psalm 114, 115 September 1 Psalm 146, 147 July 4 Psalm 36, 37 July 24 Psalm 76, 77 August 13 Psalm 116, 117 September 2 Psalm 148, 149 July 5 Psalm 38, 39 July 25 Psalm 78, 79 August 14 Psalm 118 September 3 Psalm 150 How to use this Psalms reading guide: • Read consistently, but it’s okay if you get behind. -

Psalms Commentary

I YOU CAN UNDERSTAND THE BIBLE PSALMS: THE HYMNAL OF ISRAEL BOOK I BOB UTLEY PROFESSOR OF HERMENEUTICS (BIBLE INTERPRETATION) STUDY GUIDE COMMENTARY SERIES OLD TESTAMENT, VOL. 9B BIBLE LESSONS INTERNATIONAL MARSHALL, TEXAS 2012 www.BibleLessonsIntl.com www.freebiblecommentary.org Copyright ©2012 by Bible Lessons International, Marshall, Texas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. Bible Lessons International P. O. Box 1289 Marshall, TX 75671-1289 1-800-785-1005 ISBN 978-1-892691-37-8 The primary biblical text used in this commentary is: New American Standard Bible (Update, 1995) Copyright ©1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation P. O. Box 2279 La Habra, CA 90632-2279 The paragraph divisions and summary captions as well as selected phrases are from: 1. The New King James Version, Copyright ©1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 2. The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Copyright ©1989 by the Division of Christian Education of National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U. S. A. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 3. Today’s English Version is used by permission of the copyright owner, The American Bible Society, ©1966, 1971. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 4. The New Jerusalem Bible, copyright ©1990 by Darton, Longman & Todd, Ltd. and Doubleday, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. www.freebiblecommentary.org The New American Standard Bible Update — 1995 Easier to read: } Passages with Old English “thee’s” and “thou’s” etc. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

PSALMS 60 and 61

PSALMS 60 and 61 Old Testament history confirms the truth that when God has been rejected by his people-- the nation of Israel--he delivers them into the hands of her enemies. In this 60st psalm, Israel is suffering persecution from the Arameans. This psalm commemorates one memorable part of that battle, when Joab returns and kills 12,000 Edomites in the Valley of Salt. David praises God for the triumph, recognizing that the help of man is vain. Psalm 60 For the choir director; according to Shushan Eduth. A Mikhtam of David, to teach; when he struggled with Aram-naharaim and with Aram-zobah, and Joab returned, and smote twelve thousand of Edom in the Valley of Salt. 1 O God, You have rejected us. You have broken us; You have been angry; O, restore us. 2 You have made the land quake, You have split it open; heal its breaches, for it totters. 3 You have made Your people experience hardship; You have given us wine to drink that makes us stagger. 4 You have given a banner to those who fear You, that it may be displayed because of the truth. Selah 5 That Your beloved may be delivered, save with Your right hand, and answer us! 6 God has spoken in His holiness: “I will exult, I will portion out Shechem and measure out the valley of Succoth. 7 “Gilead is Mine, and Manasseh is Mine; Ephraim also is the helmet of My head; Judah is My scepter. 8 “Moab is My washbowl; over Edom I shall throw My shoe; shout loud, O Philistia, because of Me!” 9 Who will bring me into the besieged city? Who will lead me to Edom? 10 Have not You Yourself, O God, rejected us? And will You not go forth with our armies, O God? 11 O give us help against the adversary, for deliverance by man is in vain. -

Introducing the Bible Discovering the Contents and the Message of the Bible

Learning for Life Introducing The Bible Discovering the contents and the message of the Bible Revised September 2019 Overview Introducing the Bible This course will help participants understand: the time-line of the Bible, the relationship of the Old and New Testaments, the varieties of literature in the Bible And show: A variety of ways to read the Bible for yourself. Group Leaders Notes Session 1: One God, One Bible GLN Page 2 Session 2: The Old Testament as foundation for the Christian GLN Page 4 Gospel Session 3: The Bible as today’s book GLN Page 8 Session 4: The varieties of literature in the Bible GLN Page 12 Session 5: Guidelines for personal reading and listening GLN Page 14 Group Members’ Resources Session 1: Timeline activity sheet GMR Sheet 1 A Bible time-line GMR Sheet 2 Session 2: Quiz True or False? GMR Sheet 3 The story of the Old Testament GMR Sheet 4 Verses from the Psalms. GMR Sheet 6 Session 4: What do these passages tell us about God’s love? GMR Sheet 7 Session 5: The formation of the New Testament GMR Sheet 8 Bible Aids GMR Sheet 9 GLN Page 1 One God, One Bible Session One God in both Old and New Testaments, One One Bible with many themes Aim To learn about the one God of the Old and New Testaments which are united by many themes in common. Objectives Building on previous knowledge of the Bible, Helping participants reflect on their understanding of God’s nature. Suggested Programme timing 1 Opening Prayer Welcome and Introductions Up to 2 Invite participants to recall one favourite passage from the Old Testament 15 mins and one from the New to share with each other. -

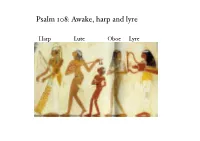

Psalm 108: Awake, Harp and Lyre

Psalm 108: Awake, harp and lyre Harp Lute Oboe Lyre Psalm 108 (107) (Mode 3. 3….12 / 4……271) Psalm 108:1-5 is borrowed from Psalm 57:7-11 and Psalm 108:6-13 is borrowed from Psalm 60:5-12. This gives us an idea how psalms were ‘up-dated’. It also gives us an indication of how careful the writers were in quoting their sources. Psalm 108 seems to belong to the Persian period (5th century BC?) when Judah, along with her neighbours, was part of a Persian province (‘satrapy’). My heart is steadfast, O God, my heart is steadfast. I will sing and make melody. Awake, my soul! Awake, O harp and lyre! I will awake the dawn. Harp Lute Oboe Lyre He stirs himself. It is not God who needs awakening, it is our hearts. ‘Awake, awake, put on strength, O arm of the Lord! … Rouse yourself, rouse yourself! Stand up, O Jerusalem!’(Isaiah 51:9,17). I will give thanks to you, O Lord, among the peoples. I will sing praises to you among the nations. For your kindness is as high as the heavens; your faithfulness extends to the clouds. Rise up, O God, above the heavens. Let your glory fill the earth. ‘By the tender mercy of our God, the dawn from on high will break upon us’(Luke 1:78). ‘Arise, shine; for your light has come, and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you’(Isaiah 60:1). Resurrection through death ‘When you have lifted up the Son of Man, then you will realise that I am he’(John 8:28). -

Psalm 113-114 Psalms Praising God for His Deliverance Psalms 113-118

Finding Yourself in the Psalms Psalm 113-114 Psalms Praising God for His Deliverance Psalms 113-118 - The HALLEL. Recited during PASSOVER, TABERNACLES, PENTECOST 113-114 Sung at the Passover Meal, after the 2nd CUP 113 - 3 Stanzas, 3 verses each. - Trinity - Praise and Deliverance 114 - Deliverance from Egypt I. Praise Him EVERYWHERE. 113:1-3 II. Praise Him EVERYONE. 113:4-6 III. The Deliverer of the NEEDY. 113:7-9 A. 113:7. “Dust” (Psalm 103:14) "for he knows how we are formed, he remembers that we are dust." B. “When you’re as low as you can get, God is there waiting to deliver you.” C. (Psalm 40:1-3) "I waited patiently for the Lord; he turned to me and heard my cry. He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire; he set my feet on a rock and gave me a firm place to stand. He put a new song in my mouth, a hymn of praise to our God. Many will see and fear and put their trust in the Lord." D. The Songs of HANNAH and MARY. 113:9 1. (1 Samuel 2:8) "He raises the poor from the dust and lifts the needy from the ash heap; he seats them with princes and has them inherit a throne of honor. “For the foundations of the earth are the Lord’s; upon them he has set the world." 2. (Luke 1:52) "He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble." 3. -

Psalm 75 — God Will Judge

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2006 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 75 — God Will Judge 1.0 Introducing Psalm 75 y Psalms 50 and 73–83 attribute their composition to Asaph. 9 There could be more than one Asaph. 9 “Asaph” might sometimes refer to a descendant of Asaph (cp. 2 Chron 35:15). y Psalm 75 shares themes and phraseology with “Hannah’s Song” (1 Samuel 2:1-10) and Mary’s “Magnificat” (Luke 1:46-55). y Placement of Psalm 75 following 74 highlights common emphases: 9 The psalmist prays for God to act (74:22-23) and He does (75:7, 10). 9 God is King (74:12) and God is Judge (75:2, 7). 9 Question of “How long?” (74:10) will be answered at “an appointed time” (75:2). 9 Both “meeting places” (74:8) and “appointed time” (75:2) translate the same Hebrew word (74:8 is the plural). 9 “Your name” occurs in both psalms (74:7, 10, 18, 21; 75:1). 2.0 Reading Psalm 75 (NAU) 75:1 A Psalm of Asaph, a Song. We give thanks to You, O God, we give thanks, For Your name is near; Men declare Your wondrous works. 75:2 “When I select an appointed time, It is I who judge with equity. 75:3 “The earth and all who dwell in it melt; It is I who have firmly set its pillars. Selah. Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs 2 Barrick, Placerita Baptist Church 2006 75:4 “I said to the boastful, ‘Do not boast,’ And to the wicked, ‘Do not lift up the horn; 75:5 “‘Do not lift up your horn on high, Do not speak with insolent pride.’” 75:6 For not from the east, nor from the west, Nor from the desert comes exaltation; 75:7 But God is the Judge; He puts down one and exalts another. -

Weekly Spiritual Fitness Plan” but the Basic Principles of Arrangement Seem to Be David to Provide Music for the Temple Services

Saturday: Psalms 78-82 (continued) Monday: Psalms 48-53 81:7 “I tested you.” This sounds like a curse. Yet it FAITH FULLY FIT Psalm 48 This psalm speaks about God’s people, is but another of God’s blessings. God often takes the church. God’s people are symbolized by Jerusa- something from us and then waits to see how we My Spiritual Fitness Goals for this week: Weekly Spiritual lem, “the city of our God, his holy mountain . will handle the problem. Will we give up on him? Mount Zion.” Jerusalem refers to the physical city Or will we patiently await his intervention? By do- where God lived among his Old Testament people. ing the latter, we are strengthened in our faith, and But it also refers to the church on earth and to the we witness God’s grace. Fitness Plan heavenly, eternal Jerusalem where God will dwell among his people into eternity. 82:1,6 “He gives judgment among the ‘gods.’” The designation gods is used for rulers who were to Introduction & Background 48:2 “Zaphon”—This is another word for Mount represent God and act in his stead and with his to this week’s readings: Hermon, a mountain on Israel’s northern border. It authority on earth. The theme of this psalm is that was three times as high as Mount Zion. Yet Zion they debased this honorific title by injustice and Introduction to the Book of Psalms - Part 3 was just as majestic because the great King lived corruption. “God presides in the great assembly.” within her. -

Daily Prayers and Readings June and July 2021 Summer Suns Are

Front cover page 1 Page 2 Dear friends, Daily Prayers It’s with great joy I write this, knowing that we can now be back together in the Porch Chapel for and Readings prayers. It feels like it has been a long time coming and so much has happened in between. We have worked our way through a pandemic and June and July 2021 are coming out the other side. We give thanks that so many of us are still here, and offer prayers for those who have passed on. We also give our thanks to God for those who have been endowed with scientific gifts, to create vaccines, in order that we may, little by Summer suns are glowing little, head back into life as we knew it Over land and sea; It may take some time to get back into the routine of Happy light is flowing this regular worship slot but one thing is for certain – Bountiful and free whenever the church has been open, our chapel has Everything rejoices been visited by a variety of folk who write down In the mellow rays their prayers and concerns, safe in the assurance that they will be prayed for. This witness has gone All earth’s thousand voices on for over 40 years and we pray that it continues. Swell the psalm of praise (William Walsham How, 1871) Every blessing to all, JD The weekly readings are taken from the Common Lectionary and reflect those used on the immediate Sunday in our own church and very many others.