New York Queer Punk in the 1970S Jarek Paul Ervin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Elvis Costello and Blondie

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Bridget Smith v.845.583.2179 Photos & Interviews may be available upon request [email protected] ELVIS COSTELLO & THE IMPOSTERS AND BLONDIE EMBARK ON CO-HEADLINING SUMMER TOUR, BEGINNING AT BETHEL WOODS ON SATURDAY, JULY 20TH Tickets on-sale Saturday, April 6th at 10 AM April 2, 2019 (BETHEL, NY) – Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, the nonprofit cultural center located at the site of the 1969 Woodstock festival, today announced that Elvis Costello & The Imposters and Blondie will perform at the center on July 20th as the first stop on their coast-to-coast co-headlining tour. Tickets go on-sale Saturday, April 6th at 10:00 AM at www.BethelWoodsCenter.org, www.Ticketmaster.com, Ticketmaster outlets, or by phone at 1.800.745.3000. Elvis Costello and Blondie shared spots near the top of the UK Singles Chart 40 years ago when Blondie's "Heart Of Glass” sat neck-and-neck alongside Elvis Costello & The Attraction’s "Oliver's Army” in the company of The Bee Gees, Gloria Gaynor and ABBA. The same week, Blondie's seminal album Parallel Lines reached #1 on the Album Chart while Costello's Armed Forces landed at #3. Elvis Costello & The Imposters’ last tour in late 2018 found the combo reaching new live performance peaks. The band "came out swinging” (Star Tribune) in Minneapolis, were “unstoppable” in Anaheim (OC Register) and played an “epic and euphoric” (Variety) show in LA that even at nearly three hours “[left] ‘em wanting more.” The Imposters are: Steve Nieve (keyboards), Davey Faragher (bass) and Pete Thomas (drums). -

Reinblättern (Pdf)

Philipp Meinert Von den Sechzigern bis in die Gegenwart Philipp Meinert, 1983 ausgerechnet in Gladbeck geboren, erlebte im Ruhrgebiet eine solide Punksozialisation. Inhalt Studium der Sozialwissenschaften in Bochum. Seit 2010 neben seiner Lohnarbeit regelmäßiger Schreiber und Interviewer für verschiedene Online- und Print- medien, hauptsächlich für das »Plastic Bomb Fanzine«. Über dieses Buch und Einleitung ...................................... 9 2013 gemeinsam mit Martin Seeliger Herausgeber des Sammelbandes »Punk in Deutschland. Sozial- und kultur- »A walk on the wild side« 15 wissenschaftliche Per spektiven«. Lebt in Berlin. Die ziemlich queere Welt des Prä-Punks in New York ................... Lou Reed: Der bisexuelle Pate des Punk .................................. 17 Glam: Glitzernde Vorzeichen des Punk .................................. 25 »Personality Crisis« Die New York Dolls als Bindeglied 30 zwischen Punk und Glam ............................................. »Hey little Girl! I wanna be your boyfriend.« Mit den Ramones 35 wird es heterosexueller................................................ »Immer der coolste Typ im Raum« - Interview Danny Fields ............... 38 »Man Enough To Be a Woman« – Jayne County, die transsexuelle 44 Punkgeburtshelferin ................................................... Punk-Genese in England .............................................. 57 Die englische Punkrevolution als kreative Befreiung von Frauen ............. 67 Interview mit Bertie Marshall ......................................... -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts Announces Rock Show Double-Header to Kick Off Kauffman Center Presents 2017-2018 Season

NEWS RELEASE Contact: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Bess Wallerstein Huff, Director of Marketing Monday, February, 13, 2017 Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts (816) 994-7229 | [email protected] KAUFFMAN CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS ANNOUNCES ROCK SHOW DOUBLE-HEADER TO KICK OFF KAUFFMAN CENTER PRESENTS 2017-2018 SEASON Blondie & Garbage: The Rage and Rapture Tour to stop at Muriel Kauffman Theatre on July 18 Kansas City, MO – The first announced show of its 2017-18 Kauffman Center Presents season will feature two quintessential rock ‘n’ roll acts. Blondie & Garbage: The Rage and Rapture Tour will perform for one night in Muriel Kauffman Theatre on Tuesday, July 18. Tickets for the show range from $79 to $149, and go on sale to the public at 10 a.m. Friday, February 24. Tickets will be available through the Kauffman Center Box Office at (816) 994-7222, via the Kauffman Center mobile app, or online at www.kauffmancenter.org. ABOUT BLONDIE Singer-songwriter Debbie Harry, guitarist and co-writer Chris Stein, powerhouse drummer Clem Burke and their band- mates in the punk/new wave band Blondie are undeniable pop icons, their sound and sensibility as fresh as when they first topped the charts in the late 1970s. Since their groundbreaking 1978 album Parallel Lines, the members of Blondie have always been a forward-thinking – and forward-moving – group. Their brand of cross-genre rock has spawned hits including “Call Me,” “Rapture,” and “Heart of Glass,” bringing underground sounds into the mainstream. Blondie’s 11th studio album, Po11inator, is out in May. ABOUT GARBAGE Hailing from Madison, WI, Garbage is guitarist Duke Erikson, drummer Butch Vig, guitarist Steve Marker and lead singer Shirley Manson. -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 1 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhatt

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhattan’s East Village, CBGB was a bar and music venue which features prominently in the history of American punk rock, New Wave and Hardcore music genres. The club’s owner, Hilly Kristal, was always involved with music and musicians, having worked as a manager at the legendary jazz club Village Vanguard booking acts like Miles Davis. When CBGB first opened its doors in the early seventies the venue featured mostly country, blue grass, and blues acts (thus CBGB) before transitioning over to punk rock acts later in the decade. Many well know performers of the punk rock era received their start and earliest exposure at the club, including the Ramones, Patti Smith, Television, Blondie, and Joan Jett. During the New Wave era, performers like Elvis Costello, Talking Heads and even early performances from the Police graced the stage in the now legendary venue. Located at 315 Bowery, which is situated near the northern section of Bowery before it splits into 3rd and 4th Avenues at Cooper square, the original building on the site was constructed in 1878 and was used as a tenement house for 10 families with a shop (liquor store) on the ground floor. In 1934, 315 and 313 were combined into one building and the façade was redesigned and constructed in the Art Deco style, as documented in the 1940 tax photo. At that time, the building was occupied by the Palace Hotel with a ground floor saloon. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Jayne County Paranoia Paradise Curated by Michael Fox February 4 – March 11, 2018 Opening Reception, Sunday, February 4, 7-9Pm

For Immediate Release contact [email protected], 646-492-4076 Jayne County Paranoia Paradise Curated by Michael Fox February 4 – March 11, 2018 Opening Reception, Sunday, February 4, 7-9pm I think that my art serves as a way of putting out the fuse before it becomes a ballistic bomb of some sort. Some people are at odds with the world and they become serial killers, and others become artists. –Jayne County From February 4 – March 11, 2018, PARTICIPANT INC is honored to present Jayne County, Paranoia Paradise, the first retrospective exhibition of County’s visual artwork, curated by Michael Fox. Although County’s artistic output began in experimental theater in the late 1960s-early ‘70s, including work with Theater of the Ridiculous and in Andy Warhol’s Pork, she is perhaps most well-known as a rock singer and performer. This exhibition takes its title from one of County’s songs, Paranoia Paradise, which she famously performed as the character of “Lounge Lizard” in Derek Jarman’s 1978 film, Jubilee. Selections of her earliest known paintings and works on paper made in the early ‘80s while living in Berlin will be exhibited alongside works made up until the present, with approximately eighty pieces on view from County’s studio as well as several private collections. A presentation of related ephemeral materials from County’s archive, as well as photographs by Bob Gruen, Leee Black Childers, and Michael Fox will accompany the exhibition and further illuminate her legendary contributions to music, film, performance, as well her role as forebear and gender pioneer as the first openly transgender rock performer. -

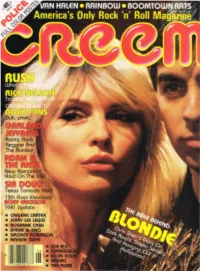

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

The Dictators Reviews

The Great Dictators | Arts | The Harvard Crimson 5/11/12 8:40 PM NEWS OPINION MAGAZINE SPORTS ARTS MEDIA FLYBY ABOUT US ADVERTISING TWITTER FACEBOOK RSS MOBILE SUBSCRIBE CLASSIFIEDS CAMBRIDGE, MA WEATHER: 44F The Great Dictators MOST READ By PETEY E. MENZ, CRIMSON STAFF WRITER 1. The Fallacy of Tuna Fish Economics Published: Thursday, April 05, 2012 2. The Delphic Renamed "The Dolphin" 3. Letter: What PBK Really Means 2 retweet 2 retweet 1 COMMENT EMAIL PRINT 4. Shielding the Vomlet 2 retweet 5. Alexander J. P. Kunkel '12 Finding High Fidelity My punk-rock years were unexpected. I grew up an hour away from Manhattan and decades away from the mid-seventies, and there was a time when these circumstances seemed the greatest tragedy of my life. That was when I spent all of my money on records and CDs, when I spent days listening to Patti Smith and Richard Hell, when there was a thrilling sense of danger in the band names “Dead Boys” and “Sex Pistols.” Punk was about disaffection, but I loved it with unfettered and unironic enthusiasm. Every band had something distinctive to listen to, and every band was amazing for it. It was during this manic stage of exploration that I discovered the Dictators, a short-lived group of Noo Yawk punks who cheerfully endorsed hamburgers, cheesy pop hits, and the suburban lifestyle. Fourteen years after they broke up, I was born, and fourteen years after that I discovered and soon fell in love with their debut album, “Go Girl Crazy.” I had purchased the record on vinyl during my freshman year, which meant I could only listen to it in my family’s living room, where my mother’s record player was permanently installed. -

Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World

Nebula 2.2 , June 2005 Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World. By Michael Angelo Tata So when the doorbell rang the night before, it was Liza in a hat pulled down so nobody would recognize her, and she said to Halston, “Give me every drug you’ve got.” So he gave her a bottle of coke, a few sticks of marijuana, a Valium, four Quaaludes, and they were all wrapped in a tiny box, and then a little figure in a white hat came up on the stoop and kissed Halston, and it was Marty Scorsese, he’d been hiding around the corner, and then he and Liza went off to have their affair on all the drugs ( Diaries , Tuesday, January 3, 1978). Privileged Intake Of all the creatures who populate and punctuate Warhol’s worlds—drag queens, hustlers, movie stars, First Wives—the drug user and abuser retains a particular access to glamour. Existing along a continuum ranging from the occasional substance dilettante to the hard-core, raging junkie, the consumer of drugs preoccupies Warhol throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s. Their actions and habits fascinate him, his screens become the sacred place where their rituals are projected and packaged. While individual substance abusers fade from the limelight, as in the disappearance of Ondine shortly after the commercial success of The Chelsea Girls , the loss of status suffered by Brigid Polk in the 70s and 80s, or the fatal overdose of exemplary drug fiend Edie Sedgwick, the actual glamour of drugs remains, never giving up its allure. 1 Drugs survive the druggie, who exists merely as a vector for the 1 While Brigid Berlin continues to exert a crucial influence on Warhol’s work in the 70s and 80s—for example, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol , as detailed by Bob Colacello in the chapter “Paris (and Philosophy )”—her street cred.