The Impact of Spontaneous Independent Npc Dialogue in Rpg Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yūrei” W Japońskich Survival Horrorach : Analiza Wybranych Przykładów

Dominika Staszenko Motyw „yūrei” w japońskich survival horrorach : analiza wybranych przykładów Replay. The Polish Journal of Game Studies 1, 29-38 2014 Dominika Staszenko Uniwersytet Łódzki Motyw yūrei w japońskich survival horrorach — analiza wybranych przykładów Wprowadzenie W japońskiej mitologii określenie yūrei odnosi się do duchów zmarłych, które z ja- kichkolwiek przyczyn powróciły na ziemię i szukają kontaktu z ludźmi [Kijewska, 2012]. Według tradycyjnych wierzeń najczęstszym powodem ich przybycia do świata doczesnego są silne związki uczuciowe z bliskimi oraz pragnienie wykonania nie- dokończonych zadań. Należy podkreślić, że chociaż zdarzają się opowieści o yūrei, w których powrót motywowany jest pozytywnymi odczuciami, takimi jak miłość czy troska, to znacznie większa część przekazów odnosi się do duchów kierujących się chęcią zemsty i zadośćuczynienia za wyrządzone krzywdy. Istoty, których jedynym celem pobytu na ziemi jest krwawy odwet, noszą nazwę onryō. Termin yūrei pierwot- nie odnosił się do wszystkich powracających duchów zmarłych, jednakże obecnie czę- ściej utożsamiany jest z postacią mściwej istoty, wymierzającej karę żyjącym. Z tego względu określenie yūrei i onryō stosuję wymiennie. Japończycy od wieków wierzą, że w świecie żywych mogą przebywać byty nadna- turalne. Takie przekonanie ma swoje źródło w systemach praktyk religijnych, takich jak buddyzm czy sintoizm. Wiara w wędrówkę dusz, opiekuńczą moc duchów zmar- łych przodków czy niemal nieograniczoną możliwość wpływania istot nadnatural- nych na egzystencję żyjących sprawia, że japońska mitologia staje się inspiracją nawet dla współczesnych tekstów kultury, ponieważ zawiera szereg uniwersalnych moty- wów, które doskonale łączą tradycję z nowoczesnością. 29 Czym jest survival horror? Wraz ze wzrostem popularności filmów grozy, opierających się na motywie pośmiert- nej zemsty, postać onryō zaczęła pojawiać się również w grach wideo z gatunku survi- val horror. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

Playing with People's Lives 1 Playing with People's Lives How City-Builder Games Portray the Public and Their Role in the D

Playing With People’s Lives 1 Playing With People’s Lives How city-builder games portray the public and their role in the decision-making process Senior Honors Thesis, City & Regional Planning Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in City and Regional Planning in the Knowlton School of Architecture at the Ohio State University By William Plumley The Ohio State University May 2018 Faculty Research Mentor: Professor Tijs van Maasakkers, City and Regional Planning Playing With People’s Lives 2 Abstract – City-builder computer games are an integral part of the city planning profession. Educators structure lessons around playtime to introduce planning concepts, professionals use the games as tools of visualization and public outreach, and the software of planners and decision-makers often takes inspiration from the genre. For the public, city-builders are a source of insight into what planners do, and the digital city’s residents show players what role they play in the urban decision-making process. However, criticisms persist through decades of literature from professionals and educators alike but are rarely explored in depth. Published research also ignores the genre’s diverse offerings in favor of focusing on the bestseller of the moment. This project explores how the public is presented in city-builder games, as individuals and as groups, the role the city plays in their lives, and their ability to express their opinions and participate in the process of planning and governance. To more-broadly evaluate the genre as it exists today, two industry-leading titles receiving the greatest attention by planners, SimCity and Cities: Skylines, were matched up with two less-conventional games with their own unique takes on the genre, Tropico 5 and Urban Empire. -

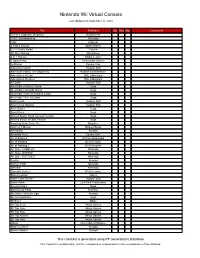

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Evolution of Game Controllers: Toward the Support of Gamers with Physical Disabilities

Evolution of Game Controllers: Toward the Support of Gamers with Physical Disabilities Dario Maggiorini(&), Marco Granato, Laura Anna Ripamonti, Matteo Marras, and Davide Gadia University of Milan, 20135 Milan, Italy {dariomaggiorini,marcogranato,lauraripamonti, davidegadia}@unimi.it, [email protected] Abstract. Video games, as an entertaining media, dates back to the ‘50s and their hardware device underwent a long evolution starting from hand-made devices such as the “cathode-ray tube amusement device” up to the modern mass-produced consoles. This evolution has, of course, been accompanied by increasingly spe- cialized interaction mechanisms. As of today, interaction with games is usually performed through industry-standard devices. These devices can be either general purpose (e.g., mouse and keyboard) or specific for gaming (e.g., a gamepad). Unfortunately, for marketing reasons, gaming interaction devices are not usually designed taking into consideration the requirements of gamers with physical disabilities. In this paper, we will offer a review of the evolution of gaming control devices with a specific attention to their use by players with physical disabilities in the upper limbs. After discussing the functionalities introduced by controllers designed for disabled players we will also propose an innovative game controller device. The proposed game controller is built around a touch screen interface which can be configured based on the user needs and will be accessible by gamers which are missing fingers or are lacking control in hands movement. Keywords: Video game Á Gaming devices Á Input device Á Game controller Á Physical disability 1 Introduction Video games, as an entertaining media, appeared around 1950. -

Helping It All Emerge Managing Crowd AI in Watch Dogs 2

Helping It All Emerge Managing Crowd AI In Watch Dogs 2 Roxanne Blouin-Payer Game Designer, Ubisoft Who Am I? Before: [email protected] Intr0ducti0n Why Emergence? • Illusion of intelligence • Interesting to watch and interact with • Create a toy sandbox What Is This About? Crowd AI Systems The Journey What’s Next? Some Context On WD Call 911! Some Context On WD2 • Vibrant and believable San Fran • Hack into humanity • Non-player centric world Anecdote Factory • Countless Anecdotes • Avoid repetition and scripted feeling • Surprise the player Anecdote Factory We know how it starts… …never how it ends! -Patrick Plourde, 2015 Anecdote Factory Cr0wd AI Syst3ms Crowd AI Systems 3 Systems • Attractors • Dynamic Attractors • Reaction System Crowd AI Systems Attractors • Spawned Activities • Based on a Game Object • Placed manually in the world Crowd AI Systems Dynamic Attractors • Using same tech as attractors • Spawned everywhere through an Event Manager • Greetings, crimes, etc. Crowd AI Systems Reaction System • Uses a stimuli based system • Emergent chain reactions • Completely systemic Crowd AI Systems General Flow Behavior A Behavior B Stimulus Decision Behavior C Ignore Crowd AI Systems Stims Propagation Reaction System Logic Rules Criteria Behavior Behavior Incident Emitter Target Ignore Observe Fight Flee Walking Insult 70% 20% 10% Walking Insult Friend 45% 50% 5% Walking Insult Enemy Friend 100% Reaction System Logic Rules Criteria Behavior Behavior Incident Emitter Target Ignore Observe Fight Flee Walking Insult 70% -

Sony Playstation

Sony PlayStation Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 007 Racing Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 101 Dalmatians II, Disney's: Patch's London Adventure Eidos Interactive 102 Dalmatians, Disney's: Puppies to the Rescue Eidos Interactive 1Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2Xtreme SCEA 2Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 3 Game Value Pack Volume #1 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #2 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #3 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #4 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #5 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #6 Agetec (Distributed by Tommo) 3D Baseball Crystal Dynamics 3D Lemmings: Long Box Ridged Psygnosis 3Xtreme 989 Studios 3Xtreme: Demo 989 Studios 40 Winks GT Interactive A-Train: Long Box Cardboard Maxis A-Train: SimCity Card Booster Pack Maxis Ace Combat 2 Namco Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere Namco Aces of the Air Agetec Action Bass Take-Two Interactive Action Man: Operation Extreme Hasbro Interactive Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600 Activision Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600: Greatest Hits Activision Adidas Power Soccer Psygnosis Adidas Power Soccer '98 Psygnosis Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron & Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft Acclaim Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron and Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft: Demo Acclaim Adventures of Lomax, The Psygnosis Agile Warrior F-111X: Jewel Case Virgin Agile Warrior F-111X: Long Box Ridged Virgin Games Air Combat: Long Box Clear Namco Air Combat: Greatest Hits Namco Air Combat: Jewel Case Namco Air Hockey Mud Duck Akuji the Heartless Eidos Aladdin in Nasira's Revenge, Disney's Sony Computer Entertainment.. -

Motyw Yūrei W Japońskich Survival Horrorach — Analiza Wybranych Przykładów

Dominika Staszenko Uniwersytet Łódzki Motyw yūrei w japońskich survival horrorach — analiza wybranych przykładów Wprowadzenie W japońskiej mitologii określenie yūrei odnosi się do duchów zmarłych, które z ja- kichkolwiek przyczyn powróciły na ziemię i szukają kontaktu z ludźmi [Kijewska, 2012]. Według tradycyjnych wierzeń najczęstszym powodem ich przybycia do świata doczesnego są silne związki uczuciowe z bliskimi oraz pragnienie wykonania nie- dokończonych zadań. Należy podkreślić, że chociaż zdarzają się opowieści o yūrei, w których powrót motywowany jest pozytywnymi odczuciami, takimi jak miłość czy troska, to znacznie większa część przekazów odnosi się do duchów kierujących się chęcią zemsty i zadośćuczynienia za wyrządzone krzywdy. Istoty, których jedynym celem pobytu na ziemi jest krwawy odwet, noszą nazwę onryō. Termin yūrei pierwot- nie odnosił się do wszystkich powracających duchów zmarłych, jednakże obecnie czę- ściej utożsamiany jest z postacią mściwej istoty, wymierzającej karę żyjącym. Z tego względu określenie yūrei i onryō stosuję wymiennie. Japończycy od wieków wierzą, że w świecie żywych mogą przebywać byty nadna- turalne. Takie przekonanie ma swoje źródło w systemach praktyk religijnych, takich jak buddyzm czy sintoizm. Wiara w wędrówkę dusz, opiekuńczą moc duchów zmar- łych przodków czy niemal nieograniczoną możliwość wpływania istot nadnatural- nych na egzystencję żyjących sprawia, że japońska mitologia staje się inspiracją nawet dla współczesnych tekstów kultury, ponieważ zawiera szereg uniwersalnych moty- wów, które doskonale łączą tradycję z nowoczesnością. 29 Czym jest survival horror? Wraz ze wzrostem popularności filmów grozy, opierających się na motywie pośmiert- nej zemsty, postać onryō zaczęła pojawiać się również w grach wideo z gatunku survi- val horror. Ewan Kirkland tłumaczy ten termin za Egenfeldtem-Nielsenem jako typ gier, w których kontrolowany przez gracza bohater musi wydostać się z zamkniętego, otoczonego przez potwory miejsca [Kirkland, 2009]. -

Well Played 3.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning Drew Davidson Et Al

Well Played 3.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning Drew Davidson et al. Published: 2011 Categorie(s): Tag(s): "Video Games" Criticism Analysis Play Literacy 1 Preface Copyright by Drew Davidson et al. & ETC Press 2011 ISBN: 978-1-257-85845-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011932994 TEXT: The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are used and reproduced with the permission of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights. Design & composition by John J. Dessler THANK YOU This third Well Played book was yet another enjoyable project full of in- teresting insights into what makes videogames great. A huge thank you to all the contributors who shared their ideas along with some insipiring analysis. A thank you to John Dessler for his great work on the book design. And thanks again to participation and support of everyone who has joined in the discussion around games being well played. And to my wife, as always. 2 Table of Contents The Deeper Game of Pokémon, or, How the world's biggest RPG inad- vertently teaches 21st century kids everything they need to know ELI NEIBURGER Hills and Lines: Final Fantasy XIII SIMON FERRARI And if You Go Chasing Rabbits: The Inner Demons of American McGee's Alice MATTHEW SAKEY Limbo ALICE TAYLOR The Neverhood; A Different Kind of Never Never Land.You Had Me at Claymation STEPHEN JACOBS Heavy Rain – How I Learned to Trust the Designer JOSÉ P. -

Sony Playstation 2

Sony PlayStation 2 Last Updated on September 28, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments .hack//G.U. Vol. 1//Rebirth Namco Bandai Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 1//Rebirth: Demo Namco Bandai Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 1//Rebirth: Special Edition Bandai Namco Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 2//Reminisce Namco Bandai Games .hack//G.U. Vol. 3//Redemption Namco Bandai Games .hack//Infection Part 1: Demo Bandai .hack//Infection Part 1 Bandai .hack//Mutation Part 2 Bandai .hack//Mutation Part 2: Trade Demo Bandai .hack//Mutation Part 2: Demo Bandai .hack//Outbreak Part 3: Demo Bandai .hack//Outbreak Part 3 Bandai .hack//Quarantine Part 4 Bandai .hack//Quarantine Part 4: Demo Bandai 007: Agent Under Fire Electronic Arts 007: Agent Under Fire: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Everything or Nothing: Demo Electronic Arts 007: Nightfire Electronic Arts 007: Nightfire: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Quantum of Solace Activision 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker Acclaim 187 Ride or Die Ubisoft 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2006 FIFA World Cup EA Sports 24: The Game 2K Games 25 to Life Eidos 4x4 Evolution Godgames 50 Cent: Bulletproof Vivendi Universal Games 50 Cent: Bulletproof: Greatest Hits Vivendi Universal Games 7 Wonders of the Ancient World MumboJumbo 989 Sports 2004 Disc: Demo 989 Sports 989 Sports Sampler 2003: Demo 989 Sports AC/DC Live: Rock Band Track Pack MTV Games Ace Combat 04: Shattered Skies Namco Ace Combat 04: Shattered Skies: Greatest Hits -

Video Game News

FEBRUARY 2017 ESSENTIAL VIDEO GAME NEWS MARKET - CONSUMPTION - USE sell.fr Julie Chalmette Chairwoman Emmanuel Martin General Delegate [email protected] Anne-Sophie Montadier Communication and Marketing Manager [email protected] FEBRUARY 2017 ESSENTIAL VIDEO GAME NEWS MARKET - CONSUMPTION - USE A word from the chairwoman Editorial ELL, which has been owes its success to the developers, representing and providing manufacturers, publishers and structure to video game accessory manufacturers who Spublishers in France for over twenty combine their talents and expertise years, aims to deliver the keys to offer gamers a multitude of to understanding the market, its experiences that are ceaselessly function and its developments, at a renewed and revised. A genuine mass time when gaming and distribution leisure industry, gaming has risen to modes are rapidly changing. the position of 2nd cultural industry in France with the objective of quickly With Essential Video Game News, becoming the leading market. This the objective is to draw up a complete pop culture sees its icons go beyond inventory of the sector, presenting a the realm of video gaming. Cinema, report of the French market in 2016, cartoons or even derivative products... the trends which drive the gamers and the richness of this industry is its ability also the perspectives for development to renew itself and deliver dreams to in the coming year. gamers. Whether on a console, PC or Video gaming represents the handheld device, the playing fields are successful digital transformation continuously growing and meeting. of entertainment industries. Solidly rooted in artistic creativity and In 2016, the video game market technological innovation, gaming reached its highest level since the 4 “In 2016, the video game market reached its highest level since the peak of generation 7.” peak of generation 7 in 2008. -

Gta V Redeem and Download Ps4 Grand Theft Auto V: Premium Edition

gta v redeem and download ps4 Grand Theft Auto V: Premium Edition. The Grand Theft Auto V: Premium Edition includes the complete Grand Theft Auto V story experience, free access to the ever evolving Grand Theft Auto Online and all existing gameplay upgrades and content including The Cayo Perico Heist, The Diamond Casino & Resort, The Diamond Casino Heist, Gunrunning and much more. You’ll also get the Criminal Enterprise Starter Pack, the fastest way to jumpstart your criminal empire in Grand Theft Auto Online. GRAND THEFT AUTO V When a young street hustler, a retired bank robber and a terrifying psychopath land themselves in trouble, they must pull off a series of dangerous heists to survive in a city in which they can trust nobody, least of all each other. GRAND THEFT AUTO ONLINE Discover an ever-evolving world of choices and ways to play as you climb the criminal ranks of Los Santos and Blaine County in the ultimate shared Online experience. THE CRIMINAL ENTERPRISE STARTER PACK The Criminal Enterprise Starter Pack is the fastest way for new GTA Online players to jumpstart their criminal empires with the most exciting and popular content plus $1,000,000 bonus cash to spend in GTA Online - all content valued at over GTA$10,000,000 if purchased separately. LAUNCH YOUR CRIMINAL EMPIRE Launch business ventures from your Maze Bank West Executive Office, research powerful weapons technology from your underground Gunrunning Bunker and use your Counterfeit Cash Factory to start a lucrative counterfeiting operation. A FLEET OF POWERFUL VEHICLES Tear through the streets with a range of 10 high performance vehicles including a Supercar, Motorcycles, the weaponized Dune FAV, a Helicopter, a Rally Car and more.