Experimental Music in Catalonia from 50´S to 90'S Alter Native Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mahalta 2011 Vi Festival Internacional De Poesia De Lleida

MAHALTA 2011 VI FESTIVAL INTERNACIONAL DE POESIA DE LLEIDA (del dilluns 28 de febrer al divendres 4 de març) POETES Vicent Berenguer (País Valencià) Rosa Fabregat (Lleida) Pere Joan Martorell (Illes Balears) Ignacio Chao (Galícia) Lorenzo Oliván (Cantàbria) Álvaro Salvador (Andalusia) D. Sam Abrams (EUA) Anna Crowe (Escòcia) Taja Kramberger (Eslovènia) * * * Artistes convidats J.M. Pou, Jordi V. Pou, Frank Harrison Trio, Meritxell Nus, Richard Douglas Pennant, C.M. Sanuy, Toti Soler i Eduard Muntada Organitzen: Universitat de Lleida – Aula de Poesia Jordi Jové Institució de les Lletres Catalanes Diputació de Lleida Institut d’Estudis Ilerdencs Ajuntament de Lleida PROGRAMA MAHALTA 2011 Dilluns 28 de febrer TEATRE DE L’ESCORXADOR. SALA 2 20.00 Pou&Pou fan Poe (Inèdits d’Edgar Allan Poe) Lectura de Josep M. Pou Fotografies de Jordi V. Pou Dimarts 1 de març CAFÈ DEL TEATRE DE L’ESCORXADOR 20.00 Open Secrets FRANK HARRISON TRIO featuring RICHARD DOUGLAS PENNANT & MERITXELL NUS Frank Harrison (piano) Davide Petrocca (contrabaix) Stephen Keogh (bateria) Richard Douglas Pennant (poemes) Meritxell Nus (poemes) Producció i direcció artística: Josep Ramon Jové Dijous 3 de març EDIFICI DE LLETRES UdL (pl. Víctor Siurana). Cafeteria 19.30 Inauguració del cicle ‘Cafè Lletres’ Lectura i col·loqui dels poetes convidats al Mahalta 2011 Intervenen: Jaume Barrull, virector de la Universitat de Lleida Joan J. Busqueta, degà de la Facultat de Lletres Pere Rovira, director de l’Aula de Poesia Jordi Jové PUB ANTARES 22.00 Toti Soler & Carles M. Sanuy Cicle Veus Singulars Divendres 4 de març LA SEU VELLA. CASA DE LA VOLTA 20.00 Espectacle poètic Poetes: Vicent Berenguer (País Valencià), Rosa Fabregat (Lleida), Pere Joan Martorell (Illes Balears); Ignacio Chao (Galícia), Lorenzo Oliván (Cantàbria), Álvaro Salvador (Andalusia); D. -

Inventory of Presidential Gifts at NARA (Ie, Gifts from Foreign Nations An

Description of document: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) inventory of Presidential Gifts at NARA (i.e., gifts from foreign nations and others to Presidents that were transferred to NARA by law and stored by NARA, 2016 Requested date: 15-August-2017 Released date: 18-September-2017 Posted date: 11-June-2018 Note: Material released appears to only be part of the complete inventory. See note on page 578. Source of document: FOIA Request National Archives and Records Administration General Counsel 8601 Adelphi Road, Room 3110 College Park, MD 20740-6001 Fax: 301-837-0293 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

?Toti Soler, 70 Anys

Enderrock | Joaquim Vilarnau | Actualitzat el 07/06/2019 a les 14:30 ?Toti Soler, 70 anys El genial guitarrista porta més de cinc dècades als escenaris | Malgrat no ser un cantant molt conegut és l'autor d'èxits com "Em dius que el nostre amor" o "Susanna" Toti Soler actuant al costat de Gemma Humet | Pere Masramon El compositor, guitarrista i arranjador, Toti Soler compleix avui 70 anys. Es va donar a conèixer de ben jove tocant el baix amb Els Xerracs, banda amb la qual fins i tot va tocar al Palau de la Música Catalana però que només va deixar un sol enregistrament: un EP amb quatre cançons. Posteriorment el trobem a Brenner's Folk i a Pic-Nic, on també hi havia carismàtica Jeanette. Al capdavant d'Om va dirigir l'enregistrament del primer disc de Dioptria (Concèntric, 1969) de Pau Riba, ara fa 50 anys. Però Toti es va donar a conèixer al gran públic tocant la guitarra en solitari i al costat d'Ovidi Montllor. Els àlbums Liebeslied (Edigsa, 1972) i El gat blanc (Edigsa, 1973) són bons exemples de la seva primera producció. Tot i que no és un cantant molt conegut és l'autor d'èxits com "Em dius que el nostre amor" o "Susanna", adaptació en català del tema de Leonard Cohen. Company inseparable d'Ovidi Montllor, va seguir enregistrant els seus propis discos: Laia (Zeleste-RCA, 1978), Lonely fire (Zeleste-RCA, 1979), Epigrama (Audiovisuals de Sarrià, 1985)? També ha enregistrat amb altres músics com Taj Mahal, Léo Ferré o Maria del Mar Bonet. -

Sonisphere, Fantastic Four !

www.daily-rock.com UNE PUBLICATION No 39 DU COLLECTIF AVRIL 2010 MENSUEL Daily Rock GRATUIT TOUTE L’ACTUALITÉ BRÛLANTE DU ROCK EN ROMANDIE Sonisphere, Interview : Rod y Gab, Maison D’ailleurs, Mexico, Mexiiiicooo ! p. 6 music in space ! p. 11 fantastic Fourp. 3 ! © Joseph Carlucci Greenfield, les vertes années 11 juin 2010. Au milieu de l’après-midi. Quelque part entre Berne et Zürich. Ici commencera le meilleur weekend du mois de juin… Et c’est reparti comme en 14 ! Ou pas. Ou presque. Cela dépendra surtout de la clémence du temps si les tranchées boueuses seront de la partie pour ce sixième Greenfield Festival à Interlaken. En même temps, les vétérans greenfieldiens Edito ont acquis une certaine résistance au mauvais grain. Rappelez-vous celui Daily Rockeuses, Daily Rockeurs, de 2005 où les éléments s’étaient déchaînés sabordant carrément les Le maudit printemps est là et je prestations de Nine Inch Nails et des n'ai toujours pas acquis de disque Queens Of The Stone Age ! Et 2008 estampillé 2010 ! C'est bien moi qui donnait l’impression de vivre le ça, entre les rattrapages de l'année festival au mois de janvier. Le dernier écoulée, les tueries sorties tout à la en date, ce fut pour les deux derniers fin, les rééditions et les vieilleries, je live de la grande scène de l’édition n'arrive pas à décrocher ! 2009, à savoir KoRn & Slipknot. L’expression 'Se régaler comme une Ce n'est pas faute d'essayer mais à part des promos tornade dans un camping' n’aura (que je refile pour acheter les vrais avec pochette et jamais sonné aussi juste. -

Décryptage Des Musiques Actuelles : Fusions, Mariages Et Métissages”

1 - Présentation Dossier d’accompagnement de la conférence / concert du samedi 20 juin 2009 proposée dans le cadre du projet d’éducation artistique des Trans et des Champs Libres. “Décryptage des musiques actuelles : fusions, mariages et métissages” Conférence de Pascal Bussy Concert de Aïwa Depuis juin 2006, notre cycle de conférences concerts propose un état des Afin de compléter la lecture lieux des "musiques actuelles". Du blues aux musiques électroniques, du rock de ce dossier, n'hésitez pas aux musiques du monde, nous avons dégagé huit familles en faisant ressortir les nombreux liens et passerelles qui existent entre elles. à consulter les dossiers d’accompagnement des Aujourd'hui, au terme de ce décryptage, nous avons choisi de nous précédentes conférences-concerts concentrer sur les multiples mélanges qui sont autant de défis face à des ainsi que les “Bases étiquettes forcément réductrices. de données” consacrées Nous mettrons notamment l'accent sur le parcours de plusieurs artistes aux éditions 2005, 2006, 2007 inclassables, même s'ils sont tous à priori issus de l'une de ces familles de et 2008 des Trans, tous en base. Certains y restent ancrés tout en allant s'abreuver à d'autres sources, téléchargement gratuit, sur d'autres jonglent avec tellement d'éléments qu'ils créent leur propre esthétique, d'autres encore juxtaposent deux ou plusieurs styles qui forment un puzzle aux www.lestrans.com/jeu-de-l-ouie pièces identifiables ; ces typologies ne sont pas exclusives, elles peuvent se combiner et s'interpénétrer. En analysant quelques-uns de ces itinéraires, nous montrerons qu'ils contribuent tous à construire une nouvelle géographie musicale, et que l'ouverture artistique qui en est le socle engendre chez le public surprise et saveur de la découverte, et donc un plaisir de l'écoute renouvelé. -

Skain's Domain – Episode 5

Skain's Domain – Episode 5 Skain's Domain Episode 5 - April 20, 2020 0:00:01 Moderator: Wynton, you're ready? 0:00:02 Wynton Marsalis: I'm ready. 0:00:03 Moderator: Alright. 0:00:06 WM: I wanna thank all of you for joining me once again. This is Skain's Domain, we're talking about subjects significant and trivial, with the same intensity and feeling. We're gonna talk tonight... I'm gonna start off by talking about a series we're gonna start, which is, "How to develop your ability to hear, listen to music." I think that for many years, me and a great seer of the American vernacular, Phil Schaap, argued about the importance of music appreciation. We tend to spend a lot of time with musicians, talking about music, and we forget about the general audience of listeners, so I'm gonna go through 16 steps of hearing, over the time. I'm gonna be announcing when it is, and I'm just gonna talk about the levels of hearing from when you first start hearing music, to as you deepen your understanding of music, and you're able to understand more and more things, till I get to a very, very high level of hearing. Some of it comes from things that we all know from studying music and even what we like, what we listen to, but also it comes from the many different experiences I've had with great musicians, from the beginning. I can always remember hearing when I was a kid, the story of Ben Webster, the great balladeer on tenor saxophone. -

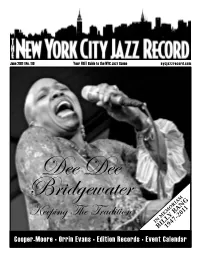

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Section I - Overview

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Street Art Subject: Los Cazadores del Sur Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE STORY SYNOPSIS INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE SECTION III – RESOURCES .................................................................................................................6 TEXTS DISCOGRAPHY WEB SITES VIDEOS BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................9 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 11 Los Cazadores del Sur preparing for a work day. Still image from SPARK story, February 2005. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES Street Art Individual and group research Individual and group exercises SUBJECT Written research materials Los Cazadores del Sur Group oral discussion, review and analysis GRADE RANGES K-12, Post-Secondary EQUIPMENT NEEDED TV & VCR with SPARK story “Street Art,” about CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS duo Los Cazadores del Sur Music, Social Studies Computer with Internet access, navigation software, -

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk Tenorsaxofonist, Født 20.10.1934 I Chicago, IL, D

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk tenorsaxofonist, født 20.10.1934 i Chicago, IL, d. 5.11.1996 Sanger og pianist som barn i baptistkirker og spillede senere vibrafon og tenorsax. Debuterede som pianist med Gene Ammons før universitetsstudier i musik. Spillede med bl.a. Cedar Walton i 7. Army Symphony Orchestra. Fik i 1961 et stort hit og jazzens første guldplade med filmmelodien "Exodus", hvad der i de følgende år gav ham visse problemer med accept i jazzmiljøet. Udsendte 1965 The in Sound med bl.a. hans egen komposition Freedom Jazz Dance, som siden er indgået i jazzens standardrepertoire. Spillede fra 1966 elektrificeret saxofon og hybrider af sax og basun. Flirtede med rock på Eddie Harris In the UK (Atlantic 1969). Spillede 1969 på Montreux festivalen med Les McCann (Swiss Movement, Atlantic) og skrev 1969-71 musik til Bill Cosbys tv-shows. Spillede i 80'erne med bl.a. Tete Montoliu og Bo Stief (Steps Up, SteepleChase, 1981) og igen med Les McCann. Som sideman med bl.a. Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, Horace Parlan og John Scofield (Hand Jive, Blue Note, 1993). Optrådte trods sygdom, så sent som maj 1996. Indspillede et stort antal plader for mange selskaber, fra 80'erne mest europæiske. Med udgangspunkt i bopmusikken udviklede Harris sine eksperimenter til en meget personlig stil med umiddelbart genkendelig, egenartet vokaliserende tone, fra 70'erne krydret med (ofte lange), humoristisk filosofisk/satiriske enetaler. Følte sig ofte underkendt som musiker og satiriserede over det i sin "Eddie Who". Kilde: Politikens Jazz Leksikon, 2003, red. Peter H. Larsen og Thorbjørn Sjøgren There's a guys (Chorus) You ought to know Eddie Harris .. -

Roberto Sierra's Missa Latina: Musical Analysis and Historical Perpectives Jose Rivera

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Roberto Sierra's Missa Latina: Musical Analysis and Historical Perpectives Jose Rivera Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ROBERTO SIERRA’S MISSA LATINA: MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND HISTORICAL PERPECTIVES By JOSE RIVERA A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Jose Rivera All Rights Reserved To my lovely wife Mabel, and children Carla and Cristian for their unconditional love and support. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work has been possible with the collaboration, inspiration and encouragement of many individuals. The author wishes to thank advisors Dr. Timothy Hoekman and Dr. Kevin Fenton for their guidance and encouragement throughout my graduate education and in the writing of this document. Dr. Judy Bowers, has shepherd me throughout my graduate degrees. She is a Master Teacher whom I deeply admire and respect. Thank you for sharing your passion for teaching music. Dr. Andre Thomas been a constant source of inspiration and light throughout my college music education. Thank you for always reminding your students to aim for musical excellence from their mind, heart, and soul. It is with deepest gratitude that the author wishes to acknowledge David Murray, Subito Music Publishing, and composer Roberto Sierra for granting permission to reprint choral music excerpts discussed in this document. I would also like to thank Leonard Slatkin, Norman Scribner, Joseph Holt, and the staff of the Choral Arts Society of Washington for allowing me to attend their rehearsals. -

THE FLAMENCO BOX in the CLASSROOM History , Evolution and Didactic Autor: Carlos Crisol Maestro

THE FLAMENCO BOX IN THE CLASSROOM History , Evolution and Didactic Autor: Carlos Crisol Maestro Coordinación de Diseño y Maquetación: Nuria Crisol de la Fuente Colaboración de los alumnos del CFGM Preimpresión en Artes Gráficas IES Santo Reino: Juan Jesús Mesa Moraleda y Gema Moreno Serrano en diseño de interiores y portada - contraportada. Traducción inglés: Nuria Sánchez INDEX I. PRECEDENTS AND ANALOGIES OF THE BOX Introduction and state of the issue Pg. 2 Searching for a box history in the world Pg. 3 The box in Perú: Findings documented on the origin of the box Pg. 5 The box in Cuba Pg. 7 The box in Spain: origin and evolution Pg. 8 . II. CONSTRUCTION OF THE BOX Building materials Pg. 12 Sundbox. Cubic capacity and dimensions of the box Pg. 14 Sound output: box hole (back, side, bottom ...) Pg. 15 Front or struck cover Pg. 18 String tension and tuning system. Treatment of harmonics. String arrangements in the box. Pg. 26 III. THE FLAMENCO BOX IN THE CLASSROOM Introduction Pg. 39 Objectives concretion Pg. 41 Subjects and curriculum areas relation: Pg. 43 Music Plastic and Visual education (Art) Language Social sciences, Geography and History Maths Physical education Languages Techology and Informatics Contribution to the Basic Competences: Pg. 45 Linguistic communication competence Mathematical competence Knowledge and interaction with the physical environment competence Information management and digital competence Social and citizen competence Cultural and Artistic competence Learning to learn competence Autonomy and self-esteem competence. IV. FLAMENCO BOX TEACHING AND LEARNING METHODS Pg. 48 V. BIBLIOGRAPHY. Pg. 51 1 Introduction and state of the issue.