MESSENGER DATA REVEALS Another Side of Mercury an Interview with Planetary Geologist Paul K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of Volatiles in Permanently Cold Areas of Mercury’S North Polar Region

Icarus 281 (2017) 19–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of volatiles in permanently cold areas of Mercury’s north polar region ∗ M.L. Delitsky a, , D.A. Paige b, M.A. Siegler c, E.R. Harju b,f, D. Schriver b, R.E. Johnson d, P. Travnicek e a California Specialty Engineering, Pasadena, CA b Dept of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA c Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ d Dept of Engineering Physics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA e Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA f Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft during its flyby and orbital observations of Mercury in 2008– Received 3 January 2016 2015 indicated the presence of cold icy materials hiding in permanently-shadowed craters in Mercury’s Revised 29 July 2016 north polar region. These icy condensed volatiles are thought to be composed of water ice and frozen Accepted 2 August 2016 organics that can persist over long geologic timescales and evolve under the influence of the Mercury Available online 4 August 2016 space environment. Polar ices never see solar photons because at such high latitudes, sunlight cannot Keywords: reach over the crater rims. The craters maintain a permanently cold environment for the ices to persist. Mercury surface ices magnetospheres However, the magnetosphere will supply a beam of ions and electrons that can reach the frozen volatiles radiolysis and induce ice chemistry. -

Bepicolombo - a Mission to Mercury

BEPICOLOMBO - A MISSION TO MERCURY ∗ R. Jehn , J. Schoenmaekers, D. Garc´ıa and P. Ferri European Space Operations Centre, ESA/ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany ABSTRACT BepiColombo is a cornerstone mission of the ESA Science Programme, to be launched towards Mercury in July 2014. After a journey of nearly 6 years two probes, the Magneto- spheric Orbiter (JAXA) and the Planetary Orbiter (ESA) will be separated and injected into their target orbits. The interplanetary trajectory includes flybys at the Earth, Venus (twice) and Mercury (four times), as well as several thrust arcs provided by the solar electric propulsion module. At the end of the transfer a gravitational capture at the weak stability boundary is performed exploiting the Sun gravity. In case of a failure of the orbit insertion burn, the spacecraft will stay for a few revolutions in the weakly captured orbit. The arrival conditions are chosen such that backup orbit insertion manoeuvres can be performed one, four or five orbits later with trajectory correction manoeuvres of less than 15 m/s to compensate the Sun perturbations. Only in case that no manoeuvre can be performed within 64 days (5 orbits) after the nominal orbit insertion the spacecraft will leave Mercury and the mission will be lost. The baseline trajectory has been designed taking into account all operational constraints: 90-day commissioning phase without any thrust; 30-day coast arcs before each flyby (to allow for precise navigation); 7-day coast arcs after each flyby; 60-day coast arc before orbit insertion; Solar aspect angle constraints and minimum flyby altitudes (300 km at Earth and Venus, 200 km at Mercury). -

The Search for Another Earth – Part II

GENERAL ARTICLE The Search for Another Earth – Part II Sujan Sengupta In the first part, we discussed the various methods for the detection of planets outside the solar system known as the exoplanets. In this part, we will describe various kinds of exoplanets. The habitable planets discovered so far and the present status of our search for a habitable planet similar to the Earth will also be discussed. Sujan Sengupta is an 1. Introduction astrophysicist at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bengaluru. He works on the The first confirmed exoplanet around a solar type of star, 51 Pe- detection, characterisation 1 gasi b was discovered in 1995 using the radial velocity method. and habitability of extra-solar Subsequently, a large number of exoplanets were discovered by planets and extra-solar this method, and a few were discovered using transit and gravi- moons. tational lensing methods. Ground-based telescopes were used for these discoveries and the search region was confined to about 300 light-years from the Earth. On December 27, 2006, the European Space Agency launched 1The movement of the star a space telescope called CoRoT (Convection, Rotation and plan- towards the observer due to etary Transits) and on March 6, 2009, NASA launched another the gravitational effect of the space telescope called Kepler2 to hunt for exoplanets. Conse- planet. See Sujan Sengupta, The Search for Another Earth, quently, the search extended to about 3000 light-years. Both Resonance, Vol.21, No.7, these telescopes used the transit method in order to detect exo- pp.641–652, 2016. planets. Although Kepler’s field of view was only 105 square de- grees along the Cygnus arm of the Milky Way Galaxy, it detected a whooping 2326 exoplanets out of a total 3493 discovered till 2Kepler Telescope has a pri- date. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

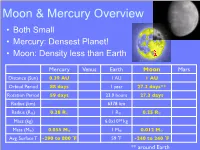

Moon & Mercury Overview

Moon & Mercury Overview • Both Small • Mercury: Densest Planet! • Moon: Density less than Earth Mercury Venus Earth Moon Mars Distance (Sun) 0.39 AU 1 AU 1 AU Orbital Period 88 days 1 year 27.3 days** Rotation Period 59 days 23.9 hours 27.3 days Radius (km) 6378 km Radius (R⊕) 0.38 R⊕ 1 R⊕ 0.25 R⊕ Mass (kg) 6.0x1024 kg Mass (M⊕) 0.055 M⊕ 1 M⊕ 0.012 M⊕ Avg. Surface T -290 to 800 F̊ 59 F̊ -240 to 240 F̊ ** around Earth Lunar Surface • Cratered – 30,000 big (> 1km) – millions of smaller craters MercurianMercury Surface - Surface Features Messenger Images Era of Heavy Bombardment Period of intense impacts in the inner S.S. by leftover planetesimals from outer S.S. 4.1-3.8 billion yrs ago affects all Terr. planets Lunar Surface • Dark Maria (“Seas”) • Lighter Highlands (“Lands”, Terrae) Lunar Surface • Maria What’s different? Why? • Highlands Apollo Lunar Surface Maria: smooth, flat, fewer craters Highlands: VERY cratered Maria have been resurfaced! Maria Formation After Heavy Bombardment Volcanic Activity caused by heat from radioactive decay flooded old craters Dating the Lunar Surface Crater Counting! Which is oldest? The Moon - Space Exploration • Luna 3 (Russia), 1959 Luna 3 farside • NASA Rangers (Impactors), 1961-1965 • Orbiters (99% mapped), 1966-1967 • Surveyors (landers), 1966-1968 • Apollo (manned), 1968-1972 • Clementine (Multi-wavel. mapping), 1994 • Prospector (polar orbiter), 1998 • SMART-1 (ESA Impactor), 2003-2006 • Kaguya (Japan), 2007- Prospector • Chang-e 1 (China), 2007- • Chandrayaan (India), 2008- Orbiter • Lunar Recon. -

Mercury Redux

FEATURE Mercury redux In January 2008, 33 years after Mariner 10 fl ew past the solar system’s innermost planet, MESSENGER crossed Mercury’s magnetosphere. Ancient volcanoes, contractional faults, and a rich soup of exospheric ions give clues to Mercury’s structure and dynamical evolution. Th e Mercury fl yby of the MESSENGER two have not been ruled out, but for those (Mercury surface, space environment, mechanisms shorter-wavelength magnetic geochemistry and ranging) probe was the features would be expected, which were not fi rst of three braking manoeuvres for the observed during the MESSENGER fl yby1. spacecraft , in preparation for its insertion Recent libration observations that require into a polar orbit in 2011. Th e probe a partially molten core11, and the limited achieved the closest approach (201 km) of contraction of Mercury, which implies a Mercury’s surface yet, and took a variety largely molten core, favour a convective of measurements in the magnetosphere, dynamo origin for Mercury’s magnetic fi eld. exosphere and on Mercury’s surface. Some Although Mercury’s magnetosphere of the fi rst results of the MESSENGER looks like a miniature version of Earth’s, mission1–6 reveal Mercury as a planet with Mercury’s relatively weak magnetic richly interconnected dynamics, from fi eld implies that its dynamo must work the dynamo in its molten outer core, a diff erently from that of the Earth. Th e crust and surface with great lobate faults geodynamo, which gives the Earth its and relatively young volcanoes, to a strong magnetic fi eld, is thought to operate magnetosphere that interacts with the core in a magnetostrophic regime in which the dynamo and the interplanetary solar wind. -

The Composition of Planetary Atmospheres 1

The Composition of Planetary Atmospheres 1 All of the planets in our solar system, and some of its smaller bodies too, have an outer layer of gas we call the atmosphere. The atmosphere usually sits atop a denser, rocky crust or planetary core. Atmospheres can extend thousands of kilometers into space. The table below gives the name of the kind of gas found in each object’s atmosphere, and the total mass of the atmosphere in kilograms. The table also gives the percentage of the atmosphere composed of the gas. Object Mass Carbon Nitrogen Oxygen Argon Methane Sodium Hydrogen Helium Other (kilograms) Dioxide Sun 3.0x1030 71% 26% 3% Mercury 1000 42% 22% 22% 6% 8% Venus 4.8x1020 96% 4% Earth 1.4x1021 78% 21% 1% <1% Moon 100,000 70% 1% 29% Mars 2.5x1016 95% 2.7% 1.6% 0.7% Jupiter 1.9x1027 89.8% 10.2% Saturn 5.4x1026 96.3% 3.2% 0.5% Titan 9.1x1018 97% 2% 1% Uranus 8.6x1025 2.3% 82.5% 15.2% Neptune 1.0x1026 1.0% 80% 19% Pluto 1.3x1014 8% 90% 2% Problem 1 – Draw a pie graph (circle graph) that shows the atmosphere constituents for Mars and Earth. Problem 2 – Draw a pie graph that shows the percentage of Nitrogen for Venus, Earth, Mars, Titan and Pluto. Problem 3 – Which planet has the atmosphere with the greatest percentage of Oxygen? Problem 4 – Which planet has the atmosphere with the greatest number of kilograms of oxygen? Problem 5 – Compare and contrast the objects with the greatest percentage of hydrogen, and the least percentage of hydrogen. -

Torrid Mercury's Icy Poles

Fire and ice The MESSENGER spacecraft reveals water ice lurking in Torrid Mercury’s icy poles deeply shadowed craters near the innermost planet’s poles. by James Oberg Color explodes from Mercury’s surface in this enhanced-color mosaic. The yellow and orange hues signify relatively young volcanic plains, while blue represents older terrain. The planet’s equator runs horizon- he saga of water ice hiding in GEochemistry, and Ranging — started Planetary scientist David Paige of the works best when good observations are tally through the center of this image; the poles lie at top and bottom. NASA/JHUAPL/CIW the shadows on Mercury ranks orbiting Mercury in March 2011 and has University of California, Los Angeles, a guided by theory.” among the most fascinating been returning reams of data ever since. participating scientist on the MESSENGER During the past several decades, scien- chapters in the history of plan- The discovery of ice contains its own sur- project, stresses the wider significance of tists have come to realize that a conspiracy to the planet nearly 40 years ago, could not Untangling Mercury’s web etary exploration. And the prises and new mysteries. the ice story. “The Mercury discoveries of freak accidents involving Mercury’s make the observations necessary to prove It took centuries for astronomers to deci- story didn’t end a year ago Scientists had suspected for decades that demonstrate the power of theory and motion and orientation had created small the case. Still, radar observations from pher Mercury’s physical and dynamic when scientists using NASA’s water ice might survive in corners of the imagination in astronomy and planetary regions on the planet’s surface where it Earth did detect unusually reflective characteristics and to understand their MESSENGER spacecraft con- solar system’s innermost world. -

NASA and Planetary Exploration

**EU5 Chap 2(263-300) 2/20/03 1:16 PM Page 263 Chapter Two NASA and Planetary Exploration by Amy Paige Snyder Prelude to NASA’s Planetary Exploration Program Four and a half billion years ago, a rotating cloud of gaseous and dusty material on the fringes of the Milky Way galaxy flattened into a disk, forming a star from the inner- most matter. Collisions among dust particles orbiting the newly-formed star, which humans call the Sun, formed kilometer-sized bodies called planetesimals which in turn aggregated to form the present-day planets.1 On the third planet from the Sun, several billions of years of evolution gave rise to a species of living beings equipped with the intel- lectual capacity to speculate about the nature of the heavens above them. Long before the era of interplanetary travel using robotic spacecraft, Greeks observing the night skies with their eyes alone noticed that five objects above failed to move with the other pinpoints of light, and thus named them planets, for “wan- derers.”2 For the next six thousand years, humans living in regions of the Mediterranean and Europe strove to make sense of the physical characteristics of the enigmatic planets.3 Building on the work of the Babylonians, Chaldeans, and Hellenistic Greeks who had developed mathematical methods to predict planetary motion, Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria put forth a theory in the second century A.D. that the planets moved in small circles, or epicycles, around a larger circle centered on Earth.4 Only partially explaining the planets’ motions, this theory dominated until Nicolaus Copernicus of present-day Poland became dissatisfied with the inadequacies of epicycle theory in the mid-sixteenth century; a more logical explanation of the observed motions, he found, was to consider the Sun the pivot of planetary orbits.5 1. -

Large Impact Basins on Mercury: Global Distribution, Characteristics, and Modification History from MESSENGER Orbital Data Caleb I

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E00L08, doi:10.1029/2012JE004154, 2012 Large impact basins on Mercury: Global distribution, characteristics, and modification history from MESSENGER orbital data Caleb I. Fassett,1 James W. Head,2 David M. H. Baker,2 Maria T. Zuber,3 David E. Smith,3,4 Gregory A. Neumann,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 Christian Klimczak,5 Robert G. Strom,7 Clark R. Chapman,8 Louise M. Prockter,9 Roger J. Phillips,8 Jürgen Oberst,10 and Frank Preusker10 Received 6 June 2012; revised 31 August 2012; accepted 5 September 2012; published 27 October 2012. [1] The formation of large impact basins (diameter D ≥ 300 km) was an important process in the early geological evolution of Mercury and influenced the planet’s topography, stratigraphy, and crustal structure. We catalog and characterize this basin population on Mercury from global observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft, and we use the new data to evaluate basins suggested on the basis of the Mariner 10 flybys. Forty-six certain or probable impact basins are recognized; a few additional basins that may have been degraded to the point of ambiguity are plausible on the basis of new data but are classified as uncertain. The spatial density of large basins (D ≥ 500 km) on Mercury is lower than that on the Moon. Morphological characteristics of basins on Mercury suggest that on average they are more degraded than lunar basins. These observations are consistent with more efficient modification, degradation, and obliteration of the largest basins on Mercury than on the Moon. This distinction may be a result of differences in the basin formation process (producing fewer rings), relaxation of topography after basin formation (subduing relief), or rates of volcanism (burying basin rings and interiors) during the period of heavy bombardment on Mercury from those on the Moon. -

First Look at Mercury

PLANETARY SCIENCE Mariner 10 was launched to Mercury by way of Venus on November 3, 1973. It was not the first probe to visit Venus. Both the United States and the Soviet Union previously have sent probes to that mysterious, cloud-shrouded planet. However, Mariner 10 was the first to photographically explore the close-up appearance of the planet, and did so both in visibIe and in ultraviolet light. And Mariner 10 was the first probe of any kind to penetrate interplanetary space beyond the orbit of Venus and to achieve a close look at the planet Mercury. First Look Why go to Mercury? Who needs it? There basically are two kinds of reasons. The first is simple and profound and at Mercury difficult to quantify: The very act of exploration is a positive, cultural activity. No one knows what is going to be found. Finding out what Mercury, what Mars, or BRUCE C. MURRAY what the moon is really like, enlarges the consciousness of all the people who partake of that new reality. TV pictures are of special importance because they provide a way both for the scientist to discover features and concepts he could not have imagined and for the public to directly appreciate and participate in the exploration of a new world. Why go to Mercury? Who needs it? But there are more specific scientific objectives as well. For Mercury, the basic-and anomalous-scientific fact is A planetary scientist that it is a very dense planet: It contains a great amount of tells what the voyage mass for its size.